Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Akane the Catgirl

Posts: 1091 Location: LA, Baby! |

|

||

|

Impressive! I remember reading the beginning of Cyborg 009 a looooong time ago before it just dropped by the wayside. I should really get around to actually reading the entire thing.

Also, how could you go through Tezuka-sensei's contributions and NOT mention Princess Knight!? That's one of his most famous works! How dare you, good sir? (Right now, my plan is to post my Ouran recap of Episode 5 tomorrow for Valentine's. What better way to celebrate the day of love than a plot about twin brothers hating each other?) |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

Madam, you impugn my good name unjustly! Surely, you must realise that I'm reviewing these artworks in order of their release. Sapphire doesn't make an appearance until 2 April 1967. As a truly authentic beautiful fighting girl - not a mere prototype - you can rest assured she won't be overlooked. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girls index

**** Beautiful Fighting Girl # 2: Sally Yumeno

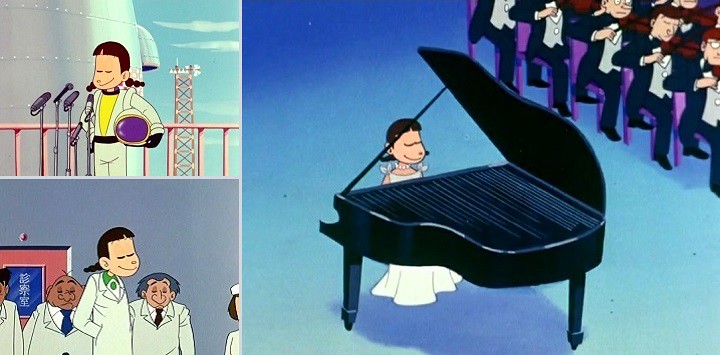

Sally (top), the Hanamura triplets, and magical boy Cub. The boys love to get up to mischief. Sally the Witch (Episodes 1-6 and 42-48) Synopsis: Fed up with her arduous study in the magical realm, the young witch Sally travels to the human world. Not altogether happy about it, her parents - the rulers of the realm - conclude it will help her development as a future queen. Just in case, they send Cub, a diminutive shape changer, to keep an eye on her. Sally and Cub quickly makes friends - the tomboyish Yoshiko and her unruly triplet younger brothers as well as the sweet natured Sumire. Adventures, trials and misunderstandings ensue. Production details: Premiere: 5 December 1966 Source material: the manga Mahou Tsukai Sunny, (ie, Sunny the Witch) in Ribon, by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, published July 1966 - 1967. (He also gave us Tetsujin 28-go, aka Gigantor, and Giant Robo.) Studio: Toei Doga Directors: Hiroshi Ikeda, Harume Kosaka, Hiromichi Matano, Yoshikata Nitta and Kazuhisa Takenouchi Music: Asei Kobayashi (Hayao Miyazaki was a key animator for episodes 77 and 80.) Background: The first manga to provide a prototype of the magical girl is generally regarded as Osamu Tezuka's Princess Knight, which began in 1953. While its titular heroine doesn't have magical powers as such, the fantasy setting contains some of the tropes that would be found in the later magical girl titles. Fujio Akatsuka created the first manga featuring a girl protagonist with magical powers - Himitsu no Akko-chan (ie, Akko-chan's Secrets) - which was published from July 1962 to September 1965 in Shueishas Ribon magazine. Shortly afterwards the same magazine also published Sunny the Witch, which managed to pip the other two manga to become not only the first magical girl anime as Sally the Witch, but the first shojo anime full stop. In Beautiful Fighting Girl Tamaki Saito notes that the American sitcom Bewitched, which was popular in Japan, inspired Sally the Witch, but, in typical Japanese fashion, the makers transformed the witch from adult to child. He also points out that Cyborg 009 had already made the connection between sexuality and violence, albeit with a token female squad member - "the single splash of crimson". So it is that in Sally the Witch, a show marketed to young girls, we get a female protagonist bringing together for the first time some of the essential elements of anime's beautiful fighting girl. Jonathon Clements in Anime: A History observes ironically that it adapted "the male-oriented, superhero-derived themes of transformation for a female audience that favoured magic, fashion and family." The elements that so captivate otaku are falling into place.

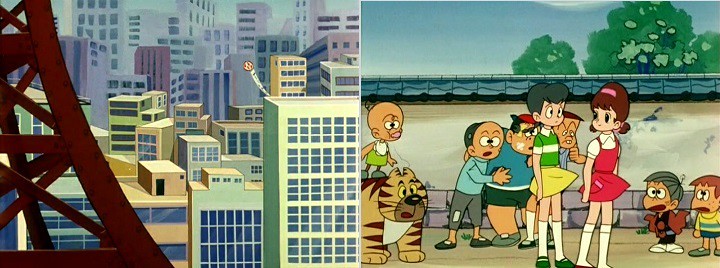

The Tokyo Tower often appears in magical girl anime, so it will be fun to trace the development of Tokyo through the trope. Sally the Witch was initially broadcast in black in white, but upgraded to colour for the eighteenth episode. Comments: One of my frustrations in this survey is the difficulty in obtaining English subtitled (let alone dubbed) versions of some of the older anime. Few of the notable early shojo anime were aired in the Anglophone world, while English speaking fansubbers seem to have likewise overlooked them. By all accounts they were popular in continental Europe and South America, so French, Spanish, Italian and even Polish fansubbed versions are available. Pity I can't understand those languages. My loss. With only thirteen episodes available to watch fansubbed in English (out of 109 made in the first run of Sally the Witch), they may not be representative of the majority. Researching the anime reveals that one of the main characters - Cub or Cabu - has a significant behavioural change late in the series, which isn't foreshadowed in the episodes I've seen. Sally begins as a wilful, bored girl who would rather raid her mother's wardrobe than do her school work. Her parents are the rulers of the magic world, so she is destined to be its queen. Note immediately how she isn't a princess to be married off - her role as the future monarch is repeatedly stressed. From the start she has agency. Sally makes her own decisions based on her own judgements. She is prepared to use magic according to her principles, and isn't afraid to violently, but humorously in a cartoonish way, mete out justice to villains. The decision to come to earth is hers, taken without her parents' knowledge, though they will acquiesce when they realise how it is improving her character. While her wilfulness never grows into spite, among the charms of the anime are the regular pranks she, Cub and the triplets play on each other. More on that shortly. Unsurprisingly, she has those qualities which are (or were fifty years ago) admired by the Japanese - politeness (unless the recipient is undeserving), loyalty, a strong and outspoken sense of justice, and a desire to do good. If that sounds a bit dull then, yeah, she's a bit dull. Most of my amusement is provided by the other characters. My favourite turned out to be the droll, tomboyish, slightly goofy, gravelly-voiced Yoshika, or Yo-chan as Sally calls her. Her situation, more than Sally's, sets the social tone of the series. Unlike the purebred Sally or the sweet but vacuous Sumire, life for Yoshika ranges from vexatious to challenging. First off, she has, in triplicate, horrors for younger brothers, though they are endearing in their way. While they, mostly, treat her well, the moment she turns her back, the mayhem starts. She is their only parental figure - their mother is dead and their father works long hours driving taxis for meagre wages - so she has to watch over them and keep house. It doesn't help that their rent is in arrears and their landlord wants to evict them. With the destructive behaviour of the triplets I can sort of understand his point of view, but I'm rooting for Yoshiko and the boys, who give him what he deserves. She means well and aspires to better things, but she too often ends up the clown, though a very sympathetic one. The episode where she dreams about her possible future careers (and simultaneously body swaps with a cat) is the pick of the bunch I've seen. It includes a concert sequence featuring Tchaikovsky's first piano concerto that had me in fits of laughter. Put upon, struggle-class Yoshiko playing Tchaikovsky with a serene expression on her face is priceless. I watched it again two days later and was in fits of laughter all over again. (It's worth noting that the piece was "the" sound of classical music in the sixties. Van Cliburn's 1958 recording was the biggest selling classical album worldwide for over a decade. The combination of American pianist and Russian conductor - Kiril Kondrashin - at the height of the Cold war enchanted people. I wonder how many cultural and social cues I miss when watching these old shows, especially given that they're Japanese.)

Yoshiko as astronaut, plastic surgeon and concert pianist. In Sally the Witch a girl can aspire to anything. Cub and the triplets are a constant source of mischief. Cub - a prototype mascot character - uses his magical abilities to annoy Sally, the brothers, schoolyard bullies and goonish adults. It invariably backfires with Sally, who puts him in his place, but even more so with the Hanamura boys, who give him merry hell. By the later episodes they set traps, lie in wait, then subject him to pain and humiliation. Believe it or not they like each other. When antagonistic third parties cause trouble Sally, Cub and the triplets (if they're handy) join forces to dole out rough justice. Burglars, kidnappers, landlords and grumpy old witches alike find themselves in battered heaps. Yes, Sally the Witch is quite a violent show. It even has an episode extolling the joys of graffiti - done as a musical. The triplets move and express themselves like mime artists. One moment they are the most serene of angels, the next the most sweet of babies, next conspiratorial, finally gleefully destructive. If cornered they'll tell you, amidst rivers of tears, how tough their lives are with no mother to love them and no food on their table. Crocodile tears, of course. The social comment is fun, but bluntly applied for the most part. One episode stands out. In the Christmas 1966 episde Sally is utterly mystified by the Christmas celebrations. Unable to get an explanation from her school friends, she goes to a Tokyo shopping strip to find out, stopping people as they celebrate or shop. No one knows what the event is about, leaving Sally none the wiser. The stranger in a strange land helps us understand ourselves. As you might expect, the designs, artwork and animation are functional at best, primitive at worst. It's up to the characters. the gags and the overall positive tone to carry the show. The black and white episode are dull to look at, while the coloured episodes follow Toei's preference for the strong colours that they used in Cyborg 009, which - surprise, surprise - gets its own shout out in a classroom scene when Cub substitutes Sally's school book with a manga as she reads aloud to the class. The OP is an earworm of the worst sort while the first ED begins with otherworldly, discordant sounds before launching into a samba. The later ED joins the OP in its irritating earwoom assault.

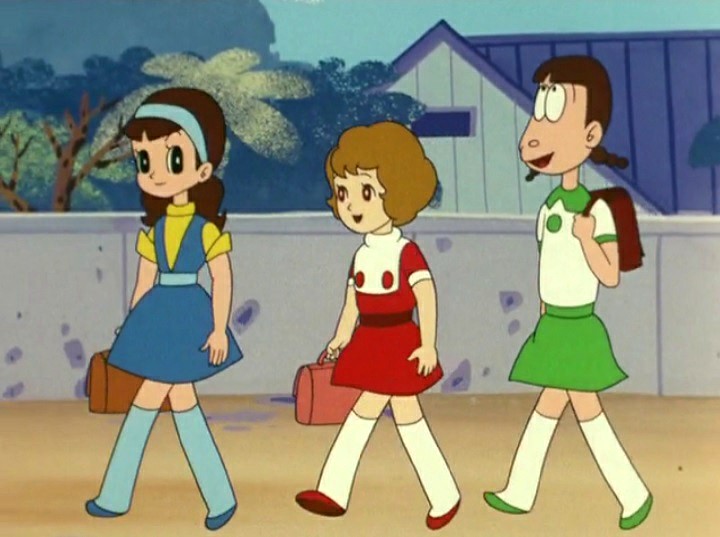

Sumire Kasugano, Sally and Yoshiko Hanamura. Zettai Ryouiki forty years before Rin Tohsaka. Rating: decent. Sally the Witch is the beginning of a revolution in anime, where female protagonists have their own agenda and fight for their principles. It introduces the magical girl and her diminutive mascot companion to television screens. The primitive artwork, especially in the black and white episodes, and animation might be a hurdle to overcome, but the fun characters and cartoon capers made this a surprisingly entertaining experience. I'd like to see more. Maybe one day. Resources: ANN The font of all knowledge Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press **** It will be at least a couple of weeks before the next review. Not only am I working overtime next weekend, but the next anime has 52 episodes - all available dubbed! Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Apr 28, 2018 11:46 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

Blood-

Bargain Hunter Bargain HunterPosts: 24154 |

|

||

|

Keep up the good work, Errinundra! - this is an absolutely fascinating anime history lesson.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Beltane70

Posts: 3972 |

|

||

|

Hard to believe that Tokyo Tower was a mere eight years old when Sally the Witch first aired! In the 26 years since I first visited Tokyo, I find it quite fascinating on how much the view of Tokyo's skyline from Tokyo Tower has changed. There were only about a dozen or so skyscrapers in Tokyo back in 1991 when I fist went (most of which were in Shinjuku) to Japan. Now, there's somewhere around fifty or so!

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

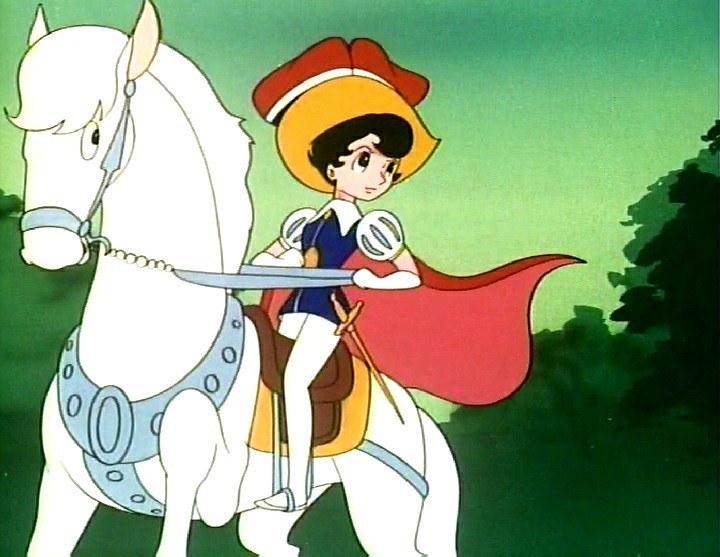

Beautiful Fighting Girl #3: Sapphire, aka Phantom Knight, aka Prince Knight, aka...

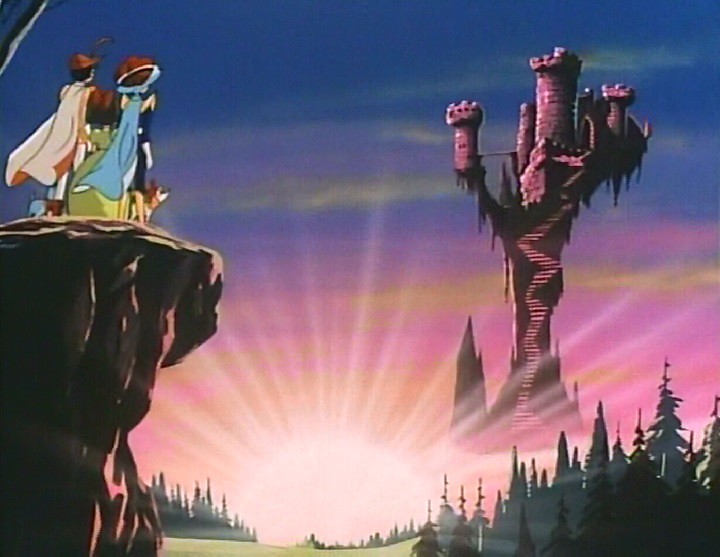

Princess Knight Synopsis: The cherub responsible for giving hearts to about-to-be-born children plays a prank by giving one child both the kind, loving, pink heart of a girl and the brave, noble, blue heart of a boy. Annoyed, God sends the angel to earth to watch over the child, who has been born as the daughter and only child to the ageing king of Silverland. Catch is, the king must have a son to inherit the throne, otherwise the slimy Duke Duralumin and his dimwitted son, Plastic, are next in line, so he announces to the world that the girl, Sapphire, is a boy. Duralumin, aided by his henchman Sir Nylon, understandably sets out to prove that Sapphire is indeed a girl. Things become even more complicated when Sapphire falls in love with the prince of neighbouring Goldland, Frank, who is unaware of her true gender; and by the powerful warlock Satan who seeks to steal Sapphire's dual hearts for his daughter, Zenda, and take over the kingdom for himself. All these complications become dire when the X Union, led by Mr X, invades Silverland and Goldland. Production details: Premiere: 2 April 1967 Source material: Ribon no Kishi (ie, Knight of Ribbons) by Osamu Tezuka, published in Nakayoshi (ie, Good Friends) magazine from January 1963 to October 1966. This, in turn was a major re-write of an earlier version published n Shojo Kurabu (ie, Girl's Club) from January 1953 to January 1956. Studio: Mushi Pro. Chief directors: Chikao Katsui and Kanji Akabori. Music: Isao Tomita Storyboards: Yoshiyuki Tomino, who would go on to direct Star of the Seine and have a hand in the creation of Space Runaway Ideon. Most importantly, he is known as the mastermind behind the Gundam franchise. Note on the release under review: The Noizumi/Hanabee set is based upon the original English dubbed TV version. It changes many of the names, re-arranges the episode order (though somewhat keeping the over-arching story order intact) and bowdlerises the violence. I shall be using the names from this release, which do, I must admit, lose something in the adaptation.

The phallic girl as protagonist finally comes to anime. Takarazuka Theatre: Osamu Tezuka spent much of his childhood in the resort town of Takarazuka, near Osaka, the home of the famous Takarazuka Review, where all roles are played by female actors. His mother was a friend of several of them, so the young Tezuka saw many performances and became something of a pet to them (a mascot, perhaps). Tezuka wrote, I was often taken by mother to the [Takarazuka] Operas, and though what they presented [was] not authentic, I got acquainted with the music and costume of the world through them. They were in turn a copy of a Broadway musical and that of a show at the Folies Bergère or the Moulin Rouge, but as I could not know the facts, I was impressed and believed they were the finest art in the world. The mostly female audience - some estimates say 90% - enjoyed performances of romantic tales involving princes and princesses with spectacular productions and elaborate costumes. Two theories (by Western scholars) on the theatre's popularity with women posit that the female audience is drawn to 1) the lesbian overtones; and 2) the female actors taking on behaviours usually attributed to men. Both are subversive, while the latter is a major thematic impulse for Princess Knight. Indeed, the theatre troupe has been attributed as an inspiration for the anime. Started in 1913, the theatre faced bankruptcy in 1974 until their various interpretations of the popular manga Rose of Versailles turned things around. Unsurprisingly, they have produced numerous shows based on stories by the local boy who made good. Comments: I often get the feeling with Tezuka's anime that he is not only fully aware that he is in the vanguard of things revolutionary, but the changes he is ringing in inform the themes of his narratives. Princess Knight is a perfect case in point. The 1953 manga, while not the first shojo manga, set the standard for the genre with its success. Pipped by a few months by Sally the Witch as the first shojo anime, the anime's narrative of a girl taking on a boy's destined role reflects the revolution taking place in anime in the 1960s - the female as protagonist, a role hitherto universally reserved for males in children's television. I can't speak for Japanese live television for children, but, as a child of the sixties, I don't recall girls as protagonists on Australian TV of the time. Girls had important roles - Saito's "single splash of crimson" - but they didn't run the narrative. (But, then, as a boy I might not have noticed.)

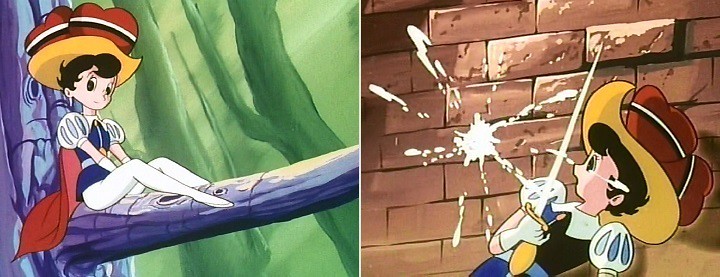

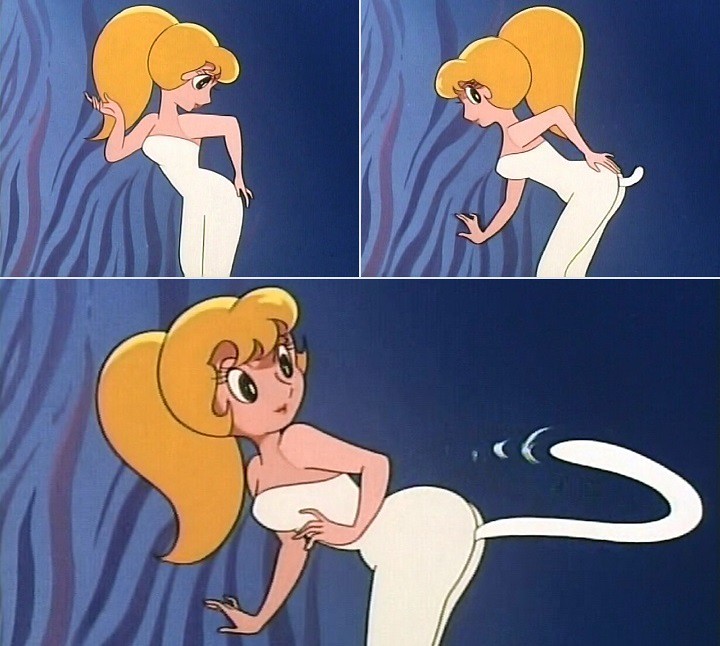

Sundry good guys and villains (top to bottom, left to right): Phantom Knight: I wonder who it might be? Prince Frank: dress him in Sapphire's clothes and you wouldn't tell the difference Sir Nylon and Duke Duralumin: the amazing thing is they are repeatedly forgiven Hellion and Satan: they just want their daughter, Zenda, to be a paragon of evil - Can anyone tell me what's written on Sapphire's leg? The wayward text appears in only one frame - Mr X: the most sinister of the villains by being calm, rational and not laughing Choppy: he sets the gender issue into play. If Sally the Witch paved the way with a female lead character, and one who fights at that, then Princess Knight completes the transformation into the phallic girl. Sapphire not only wields the phallus - figuratively with her sword, but also in her destined role as king - she has the hearts of both a girl and a boy. This raises fascinating gender questions as well as bringing to the fore issues of familial duty and personal desire. In Anime Explosion! Patrick Drazen argues that the pink and blue hearts assign gender behaviours to children whose sex has already been determined. Tezuka seems to be suggesting that sex and gender roles are unrelated. The problem is, Tezuka is, at the same time, doing things that undermine any feminist argument he may be making. Never forget that Tezuka is a perv. He is fascinated by male sexuality as the subject, and by female sexuality as the object. You see it in his early films Male and Mermaid, and his feature films A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra. From what I've seen so far, it's also at the core of his later magical girl anime Marvellous Melmo. Sapphire may be the heroine, but she also brazenly presents herself for our admiration. She flutters her eyelids, winks at us, stretches out languorously on her bed; flounces in beautiful dresses, and struts her wares (see images below). She may be in pink-heart mode in these instances, and she may otherwise be a heroine for a post-war emancipated Japanese female audience, but there's no getting around that she's also eye-candy for the male gaze (or even, perhaps, the female gaze, given her Takarazuka roots), in a way that simply isn't the case with Sally the Witch. There's something schizophrenic in Tezuka's presentation of Sapphire: as subject and heroine she reflects his feminist persona; as object of desire she reflects Tezuka quite differently. The interplay between the character as subject and viewer as subject not only adds another layer to the series, but it also introduces two more elements into anime that will be developed in the future: the female protagonist intended for a male audience - the beautiful fighting girl - and the phenomenon of the viewer as subject, which will reach its apogee with moe. What's more, Princess Knight will spawn an anime lineage of androgynous fighting girls that will take us through Star of the Seine, Rose of Versailles and Revolutionary Girl Utena. Revolutionary indeed.

Sappira Dulcis. Another aspect of Sapphire's persona is her aloneness, for want of a better word. Her parents are not only distant and unhelpful, they created many of her problems. She has no female friends at all. Her maid is a generation older, while all her other attendants are male. The many men around her are, at worst, out to kill her or, at best, buffoons. The only females her age - Zenda and Princess Charcoal - have little contact with her. Her relationship with Prince Frank, while genuinely affectionate, is mostly played out remotely, and complicated by a sequence of deceptions on Sapphire's part. Her solitude arouses the pity of the viewer - more proto-moe - but also means that the anime succeeds or fails on the viewer's reaction to her on-screen dominance. Thanks to her nature, her qualities, the themes she embodies, and her appearance, I was captivated. Shame about Carole Wyand's voice in the role, though it wasn't as agonising as Cliff Harrington's Choppy. While on the topic of voice acting, Bud Widom does a passable imitation of WC Fields as Sir Nylon, while whoever voiced Mr X stands out with his resonant tones and serious delivery. Along with its ruminations on isolation and gender, the anime frequently explores disguise, deception and authenticity. Upstanding characters and nations often have the names of precious gems and metals, such as Sapphire, Silver and Gold, while those with a more treacherous bent get names of alloys and synthetic materials such as Duralumin, Nylon and Plastic or named after worthless products like Charcoal. Princess Knight goes further than that: Sapphire's whole upbringing is an exercise in deception. Ironically, it will be the most treacherous characters - Duralumin and Nylon - who will force Sapphire's mother to reveal the truth. Accustomed to deception, Sapphire readily plays the role of the Phantom Knight to fight on behalf of the oppressed. Just as readily, she dons a wig to pose as a town girl to bewitch the heart of Prince Frank. She has a secret room in the bowels of the castle where the pink-hearted girl is given free rein to indulge her love of beautiful clothes. Zenda, appalled by her parents' gleeful rottenness, keeps her own pure heart secret - something belied by her voluptuous appearance. Nations betray each other, while the ultimate big bad, Mr X, never reveals his true identity. Best thing about him is that he is the only villain, out of many, who doesn't laugh. Yay! Oddly enough, the most authentic character is dual-hearted, androngynous, role-playing, disguise wearing Sapphire. The message is that the appearance you adopt or the role you choose or are forced to play has little bearing on your moral worth.

Zenda is a genuine magical girl who transforms. Here she grows a tail by stroking her bum. True! Along with the denser thematic material, Princess Knight consistently displays more visual flair than Sally the Witch or even Cyborg 009 - in the character designs, the animation, the colour palette and the backgrounds. Despite the limited animation there is a constant sense of activity in Mushi Pro productions. Given that the company was sliding into financial problems and that Tezuka was subsidising episode production with advances for other productions, then it represents Mushi Pro's ambitions exceeding their financial capabilities. Those ambitions did give us an anime that thematically and narratively is leaps and bounds ahead of Kimba the White Lion, but, unlike the older series, which was successfully pitched prior to its production, Princess Knight was largely made on faith. Happily it was a success in Japan and continental Europe. That all said, the fifty two episodes are more than needed to tell the most compelling parts of the tale. Some episodes aren't as engaging as others, while too many follow the basic formula of bad characters trying to kill or expose Sapphire before being defeated at the last moment. The censoring of the violence in this edition may be a bother on principle, but of more immediate concern the cuts are often awkward and sometimes bewildering. I have a fansub of the Italian broadcast of the first episode, which isn't censored so reveals the sort of frames being removed. At one point Sapphire drives the point of her rapier into the paw then nose of a wolf who is straight out of Little Red Riding Hood. In the English language version both thrusts are removed leaving an inexplicable image of the wolf with a ballooning red nose. Throughout the 52 episodes many such scenes are removed. In some instances a scene is cut short before its resolution, leaving the viewer to wonder what happened, especially when Sapphire goes from perilous situation to relief without explanation. Presumably the violence was too prolonged to doctor meaningfully. In an ANNCast interview Right Stuf and Noizomi CEO Shawne Kleckner acknowledged the problem, saying that it would have been impossible to synchronise the English soundtrack with entire episodes from Japanese sources. The cuts are an irritation, but one that can be lived with. On a happier note, the soundtrack from Isao Tomita is a treat, with complex multi-instrumental orchestrations that must have contributed to the company's problems with their bottom line. Curiously, Tomita would make a name for himself in the west as an innovator with the synthesiser. His 1974 album, Snowflakes are Dancing, consisting of synthesiser arrangements of Debussey pieces and released under the name Tomita, was a hit in the west, entering the pop charts, topping the classical charts and garnering four Emmy nominations. The OP is now a favourite of mine - the frogs bopping along to the bouncing bass lines never fail to amuse and enchant me - and nicely sets up the good natured, non-serious tone of most of the series, though things do get dark in the last quarter or so. Rating: as an anime artefact, revolutionary; for its role in the development of the beautiful fighting girl, seminal; as a viewing experience, good. A memorable lead character, fascinating thematic threads and a relatively dense narrative structure for its time that culminates in a darkly compelling invasion sequence more than compensate for the annoying cuts, episodes of insignificance, foolish support characters, and at times repetitive episode structures. Sources: ANN Tezuka in English The Font of All Knowledge Anime Explosion: The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation, Patrick Drazen, Stone Bridge Press. Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle

Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 3:24 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl #4: Atsuko Kagami, aka...

Himitsu no Akko-chan (ie, Secret Akko-chan) (Episodes 1-6 and 89-94 in the original Japanese without subtitles. Hey, I had no choice in the matter.) Synopsis: As a reward for Akko-chan's devoted behaviour - she gave a broken mirror a proper burial - the mirror spirit gives her a magical mirror compact (see image above) that enables her to transform into any human or animal form. It also connects her to every other mirror, allowing her to jump through one and out the other. Akko-chan uses her powers to solve problems and help her friends. (Note: her family name reflects - yuk! yuk! - the normal nature of the magical device.) Production details: Premiere: 6 January 1969 Source Material: Himitsu no Akko-chan by Fujio Akatsuka, published in Ribon magazine from from July 1962 to September 1965, is generally regarded as the first manga with a magical girl as the protagonist. As an anime it was pipped by Sally the Witch and by Princess Knight with its female heroine and magical elements. Writer and artist Fujio Akatsuka is most famous for creating the original Osomatsu-kun manga that inspired three television series - most recently in 2015-16. That and Tensai Bakabon led to his title as the Gag Manga King. Studio: Toei Doga Directors: Hiroshi Ikeda, Keiji Hisaoka, Masayuki Akehi, Takeshi Tamiya and Yoshio Takami. Script: Masaki Tsuji and Shun'ichi Yukimuro - they would go on to have long careers as script writers for numerous famous anime. ANN lists Isao Takahata as an assistant director and Hiyao Miyazaki as key animator in episodes 44 and 61. Comments: So, yes, I watched these 12 episodes (the first six and the last six) raw, so, given that Japanese is a foreign language to me, this post ought to be considered an impression rather than a review. I suprised myself by frequently understanding individual words, but I couldn't string any together to divine any meaning from them. That said, Himitsu no Akko-chan isn't a complex show, so by the end of the every episode I had a pretty good understanding of what happened in the previous 24 minutes thanks to the visual narrative and the character expressions. One day, in a fit of total insanity, I may watch the other 82 episodes. Secret Akko-chan is the last of the three grandmothers of magical girl anime. If you add the time elapsed since their premieres to the ages of the protagonists in those premieres Sally Yumeno would be 60 years old, Princess Sapphire 61, and Atsuka Kagami 58. Pretty much every subsequent female anime protagonist can trace her lineage back to these three characters, with a dash of Françoise Arnoul, Captain Tonga and Bai Niang added in. It's a crying shame that two of the three series aren't generally available in the anglophone world, whether by official release, which I must admit is unlikely, or by fansub. But then, the age of genuine fansubbing is pretty much over.

Atsuko mutabilis Where Sally is an alien magical girl visiting the human world and Sapphire is a straight girl (so to speak, if you ignore her cross-dressing) in a magical world, then Akko-chan is the first example of a normal girl who is given a magical device that transforms her into something different. Able to choose any human or animal appearance she wishes, Akko-chan mimics her parents, her teachers, her friends, people who are otherwise strangers, and numerous animals - most frequently birds in the episodes I saw. Compared with modern magical girls the metamorphoses are straightforward: we see her image in the mirror then, starting from the bottom of the mirror her image is replaced by the new version scrolling up. It's nothing as elaborate or excrutiating as you get in, say, Sailor Moon. That innovation is still ahead of us. What's more, the transformation doesn't give Akko-chan any fighting abilities. This sets the tone of the series, which is rarely about conflict. (The images above with the gun and sword are misleading: she uses them as a threat display only.) The narrative spur for most of the episodes is problem solving: a circus boy who lacks the courage to confront a lion; a transfer student ashamed of his father's occupation as a one-man children's puppet show performer; Akko-chan losing her mirror after she transforms into her music teacher; bringing together an old man and his lost monkey; or saving people threatened by a typhoon. One episode involved bullies stealing her mirror (without ever discovering its potential), while the local community of children includes a portly gang leader who blusters a lot but never deliberately hurts Akko-chan or her best friend Motoko Naniwa. Thanks to his carelessness and physicality, though, he knocks them down accidentally from time to time. In short, Toei is refining its appeal to young girls, away from the mory boysy mayhem of Sally the Witch. While comical by design and by nature the children in the support roles are one-dimensionally dull, but then so is Akko-chan. They can't match the gleeful violence of the Hanamura triplets from Sally the Witch, nor the narrative sophistication of Princess Knight. Himitsu no Akko-chan also lacks the eccentricities of Princess Knight. So far in this survey most of the beautiful fighting girls have come from either the Toei or Mushi studios. The Toei productions, without the pre-occupations of Mushi's Osamu Tezuka or Eiichi Yamamoto, seem more corporate, more calculated, safer and less interesting. There is a determination to stick to episodic stories and no overt sexualising of the female protagonist. Akko-chan herself is prim and proper, with little of Sapphire's flirting with the camera. Toei will survive the 1970s economic crisis, while Tezuka's Mushi will go under. Had Tezuka's vision for Mushi Pro succeeded anime may have ended up in a different place. One interesting thing about the show is that the children's families live in the old-fashioned one or two storey wooden houses that were once common in Tokyo. City shots show apartment buildings and modern trains. As a link between the two environments the children's favourite playing spot is a field littered with unused sewerage pipes, indicating that change is on the way. The depiction of rapidly evolving Tokyo will be subtly but poignantly displayed in Mushi's later Ashita no Joe. There is a moment of awesome in the final episode that transcends the show's limitations. Akko-chan's father is a ship's captain who is rarely at home. When he is in peril of running aground during a typhoon, Akko-chan uses her mirror to transmit the light from all the mirrors in Japan to show him the way. Throughout Japan mirrors go black as the light is absorbed, much to the surprise of the people using them. It reminded me of the moment in the first series of Durarara!! where all the mobile phones in the Ikebukuro shopping strip ring simultaneously. Terrific stuff.

Left: the growing city seen from Tokyo Tower; right: Akko-chan and her playmates. Rating: for its role in the creation and evolution of the magical girl, absolutely essential; as a viewing experience, not very good, but factor into that that I watched the episodes raw. Himitsu no Akko-chan introduces the ordinary, everyday girl who transforms into something else through the agency of a girl's accessory with magical powers. This promising development fails to lift the series above its limited shojo ambitions. Sally the Witch is the more entertaining of the two early Toei magical girl anime. Sources: ANN The font of all knowledge Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle My Anime List **** Changing tack now, as I journey through the history of female protagonists in anime, there are underlying arguments and theses I'm presenting. I guess I'm trying to unlock what it is about anime that it frequently gives us strong female protagonists that appeal to a male audience. How did Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind come about? Or Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit? Or Noir? Or even the Aria franchise? Or Claymore? Or Princess Tutu? Tamaki Saito's arguments, drawn from a psychology background, that otaku have adapted the distinctive non-realistic and atemporal qualities of anime in a creative sexual way, seems to me to put too much emphasis on the anime characters as object, rather than subject. I read something today that provided a key to the lock. Melbourne is the home to a simultaneously renowned and maligned photographer, Bill Henson, who came to public attention through his images of naked pubescent children and teenagers. That is, they are typical ages for many female anime characters. The self-appointed protectors of our public morals have railed against him, while the art community have vigorously supported him. Henson has tended to treat his critics with disdain. He maintains that he always has the full consent of both the children and their parents. All efforts to prove otherwise have been unsuccessful. I'm inclined to side with his supporters although I'm not that interested in his work. Today the National Gallery of Victoria opened an exhibition of recent works of his. The exhibtion's web page provides a couple of examples of the types of photographs in question. (Note: NSFW.) The national broadcaster, the ABC, to coincide with the exhibition, today published online an interview with Henson along with one of his former child models, who is now an adult. While she has no regrets about modelling for him and remains a supporter of his vision, the interesting part of the interview is this quote from Henson, "Great art is about empathy, whether it is literature or music or photography," he said. "It is about feeling the experience. "You want to hang onto that: a deep empathetic response is the ultimate response you can have. "You become the subject." That last comment is the nub of the issue. It's also ambiguous, taken out of context. Henson isn't saying that the viewer is the subject in a detached sense, as you get with pornography. Instead, the viewer is stepping into the shoes of the subject in the image and experiencing their circumstances. With the best examples of the beautiful fighting girl anime the question can now be re-stated as, "How did male viewers of anime come to empathise with female anime protagonists?" Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 3:25 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

yuna49

Posts: 3804 |

|

||

|

In a fairly typical Trigger homage, Kagari Atsuko is also name of the lead character in Little Witch Academia.

|

|||

|

|||

Blood-

Bargain Hunter Bargain HunterPosts: 24154 |

|

||

This is a deeply interesting question, the moreso because of the difference in the West. For years, the conventional wisdom - and I think it still holds mostly true today - is that girls will watch adventure cartoons that feature boys as heroes and boys will obviously watch adventure cartoons that feature boys as heroes, but boys won't watch adventure cartoons that have girls as heroes. And since in the eyes of those who make and broadcast adventure cartoons, boys are the main demographic, it's little wonder that girls are rarely seen as heroes in adventure cartoons. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

@ yuna49,

Thanks. I should've picked that up. @ Blood- It seems to me there are two ways viewers approach female protagonists. The question is whether the protagonist is subject or object. In the former the viewer identifies with, empathises with and admires the character; in the latter the viewer gazes at and is excited by the character. So far the magical girl shows I've looked at, being aimed at a shojo audience, the characters are the subject, although Princess Knight introduces elements of her being the object. Marvellous Melmo and Cutie Honey will push that tension further. (I'll be directing my gaze towards them in due course.) I think a big split will take place with the near simultaneous releases of Daicon IV and Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, where we'll see the blossomming of the two types. |

|||

|

|||

Blood-

Bargain Hunter Bargain HunterPosts: 24154 |

|

||

|

@ Errinundra - the subject/object paradigm is a little too binary for my tastes. It suggests that a straight male will view a female action protagonist as an object and thus not identify, empathise with her or admire her. I think the viewing experience is more varied than that, even if I use only myself as an example. Yes, I can be excited by the appearance of a female protagonist, but my viewing experience of her does not end there and I'm sure the same is true of many male viewers.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

^

I completely agree with you. My three favourite heroines - Akemi Homura, Rin Tohsaka and Mireille Bouquet - are each both admirable and gorgeous. Thing is, watching something because the female characters are hot isn't unique to anime. It's me, the male viewer, stepping out of my shoes, into the female character's and sharing her experiences that is interesting. I can't speak for Japanese otaku but I can share my responses and hope they resonate with others. |

|||

|

|||

Blood-

Bargain Hunter Bargain HunterPosts: 24154 |

|

||

|

Indeed. What's interesting to me is the question of why anime producers and broadcasters were able to avoid the, "boys won't watch girls being heroes" trap that the West fell into. Was it because the industry there was fortunate enough to have a visionary like Osamu Tezuka whose narrative concepts were ahead of their time? Was there some other cultural difference at play even though Japanese society was just as, if not more, patriarchal at the time? I wonder.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Having reached an significant juncture in the Beautiful Fighting Girl survey, I'll be heading in other directions for a short while.

Sword Art Online the Movie: Ordinal Scale Reason for watching: Because I could. I try to get to all the anime cinema screenings that I can here in Melbourne. Ordinal Scale is currently getting a season in 39 cinemas around Australia and 12 in New Zealand, I caught the tram from work into the city on Tuesday night to catch it at Hoyts Melbourne Central. Images are from the Madman Entertainment website. Synopsis: In the real world where Kirito, Asuna and friends are re-establishing their lives after their extended trial in Aincrad, augmented reality is taking over from virtual reality as the latest fad. A large part of its attraction is that it is seen to be safer and more practical than its predecessor. It also helps that a new AR game - Augma - allows participants to fight monsters from the Sword Art Online world on the streets of Tokyo. Even better, if the players are lucky, Augma's very own virtual pop idol, Yuna, will sing along as they fight. When Asuna starts to lose her memories of her time in Aincrad, Kirito must uncover the truth about Augma and Yuna or things could get dire all over again for the Aincrad survivors.

Kirito and Asuna: clones. Comments: If ever there was a case for seeing an anime film in its intended element, Ordinal Scale is surely it. In what is otherwise a mostly humdrum movie that I doubt would ever get much attention at home, the advantages of viewing it in a cinema bring to the fore the things it does quite well. I'm talking cinema bells and whistles here; not your pokey arthouse cinemas like the Nova in Carlton, where I've seen many an anime film previously. No criticism of Nova is intended - I'm grateful for the opportunities they've provided to see some classic anime - but there's nothing like a big screen, glorious high definition and surround sound to experience what is, when all is said and done, a monster slashfest. I'm also impressed that films such as this and Your Name are and were shown in multiple cinemas in Melbourne and Sydney. In the past only Ghibli films have had that sort of privilege. So, the fights. They involve summoning, via Augma, the Boss monsters from various levels of the Aincrad world. The beautifully realised monsters have a convincing sense of power and mass and movement. The augmented reality environment shakes and smashes and rumbles as they move and fight. There's sparks aplenty while the volume is loud, LOUD, LOUD. Fantastic. As is my wont, I sat about four rows from the front with my senses totally immersed in the violence. There's a catch with augmented reality that the film neatly camouflages: being a visual enhancement only, the boss monsters can't have a direct physical effect on the characters. The augmented apparatus (see image above) can only fool the player into experiencing the presence of the monster. When it comes down to it, the players and characters can even occupy the same space. The film gets around this by disguising the supposed impacts with lighting pyrotechnics and rapid camera movements. For sure, the monsters can "hit" the characters, who can be "killed", but only in a role-playing sense. Tension is created by making the monsters heroically fearsome, having the characters treat the fights oh-so-seriously, by adding into the fights a "real" villain who can hurt the players badly (and does), and by the growing realisation that, for the Aincrad survivors, participating in the game will have an alarming downside. But, yes, the monsters are boss.

The monster battles sparkle in an otherwise straightforward film. Now here's a confession: I've never, ever before seen a single part of the Sword Art Online franchise. Not the first episode. Not even a clip on YouTube. Thanks to my role as moderator here, as well as the ubiquity of the franchise in the anime community, I'm well aware of the two main characters, as well as the basic premise of the original series. I'm also aware of the polarising nature of the show. Thanks to the straightforward plot, my neophyte circumstances were no impediment to enjoying what the film had to offer. I wonder also whether it helped that I didn't bring any thematic baggage into the cinema. That said, the biggest surprise to me was how familiar the film seemed. The backgrounds, while detailed and at time breathtakingly vast, are in the colourful psuedo-realistic style so prevalent in anime today. Admittedly it's attractive, but It seems that studios prefer to make the scenery as convincing as possible, rather than as interesting as possible. It all seems so same-same. Even more familiar seeming are the characters. For sure, I went into the cinema aware of how Asuna and Kirito looked, though not much else about their characters, but I was quickly reassured and disappointed by how they and pretty much everyone else in the film were from the generic anime character storage cupboard. Kirito, in particular, is just another clone, in his appearnce, behaviour and role, of numerous other protagonists I've encountered in anime. He either stares blank-faced into the middle distance - I suppose he is suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome - or else putting on a regulation determined face as he goes into battle. In fairness, given the emphasis on the fight scenes within the time constraints of a film, there isn't much room for character examination or development. The story is self-contained so could well be a diversion from the main threads of the franchise. It also borrows ideas from other anime, which may also be a factor in the film's seeming familiarity. The augmented reality mechanics are strongly reminiscent of the set up in Dennou Coil while the diminutive fairy-like Yui is totally ripped from Yumomo from Chobits. That's OK, as both characters are endearingly amusing. The climactic idol concert brings to mind a similar sequence in Key the Metal Idol, while, of course, the trapped in an online game scenario of the original series goes back to .hack//SIGN. Is it just another example of anime eating itself? Or is the franchise lacking in originality? I haven't seen enough of it to form a strong opinion.

Yui in a not so Yumomo moment. Composer Yuki Kajiura continues to disappoint. Like much of her work since the Puella Magi Madoka Magica series she is more polished than inspired. While she remains the master (mistress?) of atmosphere, since those earlier glory days I've only occasionally been ear-smacked by her material. I'd like to hear her ditch the orchestral arrangements and the big ballads and go back to her techno-based soundscapes, her opera influenced progressive rock numbers and her European folk inspired accoustic pieces. Maybe I'm the one being conservative now? Rating: decent. Ordinal Scale scores what it does thanks to the thrilling fight scenes. That and the lush artwork are undermined, however, by uninteresting character writing, a mundane plot and other generic elements. I'd recommend seeing it at cinema, but I wouldn't bother seeing it at home. See also: Theron Martin's review. |

|||

|

|||

Blood-

Bargain Hunter Bargain HunterPosts: 24154 |

|

||

|

I saw Ordinal Scale last night. I consider myself a "friend" of the SAO franchise - I enjoy its popcorn entertainment value but I wouldn't consider myself a superfan or even a particularly knowledgable one. I watched the two seasons when they first came out and have not rewatched them yet, so my grasp of secondary characters and other things is not deep. Haven't read any source material or manga. How marvelous that occasionally we get to see anime movies on the big screen not long after their Japanese debut.

I enjoyed the film, although after everything that has transpired in SAO, ALO and GGO, it's a wonder our intrepid heroes continue to be willing to play online games since inevitably something bad always happens. Checkers, anyone? I don't imagine Errinundra would be any more impressed with the characterization of Kirito and Asuna even if he had seen the TV series, but as a "friend" of the franchise, I have a reasonable amount of affection for them, regardless of their lack of Tolstoyean psychological depth. It was fun to see their relationship advance. Virtually all the usual suspects got at least a cameo appearance, although as I mentioned earlier, my less than incisive memory meant that some of them didn't really register with me. I made the mistake of sitting closer to the screen than I needed, thinking it would be okay and it mostly was. I forgot when you have to read subtitles, being closer is more of a challenge. Only mid-March and already I've been able to watch two anime movies on the big screen! (Girls un Panzer Der Film being the other - I guess I missed your review of that one, Errinundra. |

|||

|

|||

|

All times are GMT - 5 Hours |

||

|

|

Powered by phpBB © 2001, 2005 phpBB Group