House of 1000 Manga

Saturn Apartments

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

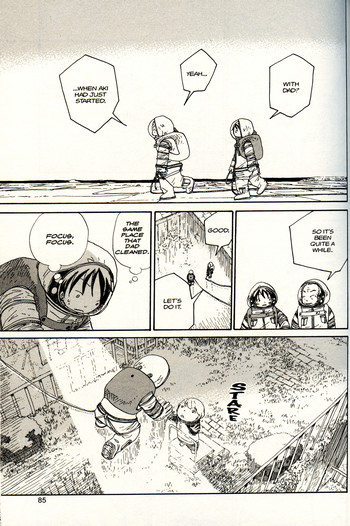

In a wistful future, humanity has abandoned Earth en masse to allow the planet to return to nature. Everyone lives, and has lived for generations, in a massive artificial ring circling the planet. A hierarchy has developed: the wealthiest citizens live at the top of the ring, where enormous windows provide natural light, while the poor inhabit the darkened lowermost stories. Down in the lower levels, Mitsu, a baby-faced teenager, dreams of following in his late father's footsteps as a space window washer, donning a spacesuit and rappelling off the sides of the ring to let the sunshine in.

Saturn Apartments is a kindly manga. Bad things happen in Mitsu's artificial world, from the daily risks shouldered by the window washers to the social inequalities that simmer under the surface of the ring society. We soon learn that Mitsu's father was killed falling off the ring to the Earth far below, and Mitsu wonders if it was really an accident; maybe his father was worn down by his harsh working-class life and committed suicide. And yet people are basically good, they look out for each other, they hold their ramshackle neighborhoods together and care for the mechanical systems that keep them all alive. In other environmental sci-fi fables, humans have to completely raze the planet before they pack up and leave (as in Wall-E) or they stay put and eject nature into space instead (as in Silent Running, a movie I find hypnotically engaging). In Saturn Apartments, you get the feeling everyone just sort of agreed to leave for the common good.

Window washing doesn't pay well or carry any prestige, but if you're not acrophobic it has its charms. Mitsu gets to know the other window washers, some of whom have been in the business for years and remember his father. He's apprenticed to a crusty old-timer, gets bullied by a tough kid who sees him as a rival, and looks up to a hulking bald guy who turns out to be a teddy bear, doting on his tiny daughter. He meets people who live full-time on the outer hull, especially a wary loner of a woman who maintains an emergency station with only her cat (which wears its own custom spacesuit) for company. And, most of all, he looks through the windows into the countless and varied living spaces below, each with its own residents and problems and stories. Inevitably, he gets involved in people's lives.

Saturn Apartments belongs to a manga tradition that ranges from Kenji Tsuruta's Spirit of Wonder (anyone remember that one?) to Kozue Amano's Aqua and Aria and Jiro Tanaguchi's The Walking Man: manga that exist primarily to transport readers to a vivid locale so they can vicariously wander around and explore. It's less about plot and conflict, more about visiting with a likeable cast of characters and looking at pretty pictures of their world. (One of the few American comics that touches on the same spirit is Linda Medley's Castle Waiting, which is basically a multi-volume excuse to join a group of fairy-tale characters in exploring a magnificent old castle—and oh, is it lovely.)

Hisae Iwakawa has the kind of welcoming visual style that make you want to submerge yourself in her drawings. Her characters are simple and cute, like round-headed dolls; Mitsu is supposedly about fifteen when the story begins but looks like a little boy, and even the elderly characters resemble children with wrinkles. But they're drawn with care, charm, and great attention to their personalities. And their surroundings are rendered with thoughtful detail, changing tone from setting to setting. Mitsu's neighborhood in the lower levels looks like a dilapidated version of one of Tokyo's outer prefectures, all makeshift market stalls and run-down buildings leaning against each other for strength. In the wealthier sectors, you see more sci-fi details: holographic transmitters, huge garden or aquatic environments. And the steel landscape of the hull, with the Earth curving majestically below, evokes the spare wonder of outer space.

As low-key and meandering as the story is, a plot slyly develops. The economic inequalities in the ring build toward mutual resentment between the castes, then the threat of all-out class warfare. Meanwhile, a couple of scientists in the lower levels come up with a revolutionary idea: would it be possible, after all this time, to send a craft to the Earth's surface? Characters who seemed like one-offs reappear as the story continues, each, as it turns out, having something to contribute to the secret Earth launch. And finally, as violence erupts in the ring, Mitsu has a chance to fulfill his impossible dream of traveling to Earth…

Saturn Apartments was one of the titles in Viz's SigIkki line, an early experiment in Web-to-print manga publishing. For a few years, Viz devoted its entire Signature line—its imprint for artsy, literary and “mature” manga—to titles from Ikki, a Japanese magazine that runs alternative manga roughly equivalent to the output of Fantagraphics or Drawn & Quarterly in the U.S. The SigIkki titles ran online first, then were collected into print if they attracted enough reader interest. Viz still publishes a lot of Ikki manga, but the SigIkki line has reverted to Signature, while the Web-to-print initiative has moved from alternative manga to more mainstream titles (and is especially vital to Viz's BL line, SuBLime). But the 2009 SigIkki launch lineup introduced American readers to a slew of offbeat gems that will probably all show up in “House of 1,000 Manga” one of these days, including Saturn Apartments, Children of the Sea, and Bakurano: Ours. It was a noble experiment.

And so is Saturn Apartments, which doesn't want to grab you with a gripping narrative or take you on a roller-coaster ride through a wild science-fiction universe. It just wants to open a door, or maybe a window, into a world of the future, in some ways a little better than our time, in some ways a little worse, but just as alive. The characters live partitioned off into isolated geometric spaces, some big, some small, some beautiful, some shabby, but almost all lonely. And then someone taps on the window, and they look up, and there we are, smiling in.

discuss this in the forum (5 posts) |