The Real Authors of Bungo Stray Dogs

by Rebecca Silverman,It's a conceit more common to straight mysteries and steampunk – plucking authors out of their times and places and plunking them down in a semi-modern world (or an alternative version of their own) to solve mysteries and fight crime. You see it all across the board – from Rémi Guérin and Guillaume Lapeyre's French comic City Hall, which pairs Amelia Earhart with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Jules Verne to fight crime in a steampunk London ruled by Mayor Malcolm X, to the more sedate Jane Austen mysteries by Stephanie Barron, one of many contemporary mystery series to turn great authors into detectives in their spare time. On the Japanese side we're much more likely to get reimaginings of famous characters than their authors, such as summer 2015's Ranpo Kitan: Game of Laplace, which took characters from Edogawa Rampo's works and updated them, or Kaori Yuki's Ludwig Kakumei, which plays with characters from The Brothers Grimm, though there have been exceptions. One airing as of this writing is Bungo Stray Dogs, a series that takes great Japanese authors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and recasts them as supernatural detective/crime fighters (or crime lords) in a world similar to our own. For Japanese viewers, most of them will be very familiar, but given the fact that most western readers aren't exposed to much beyond The Tale of Genji in terms of Japanese literature, figuring out the details behind the characters can become a little tricky. So let's take a look at some of the real people who inspired Kafka Asagiri and Sango Harukawa's story and see who is who and what is what when it comes to remaking these writers.

I'll start with Akiko Yosano, partly because she's one of my personal favorites in terms of her works, but also because of how her anime counterpart plays with her real-life poetry. Born in 1878, she's one of the longer-lived authors in the show, passing away of a stroke at age 63 in 1942. Yosano was a writer of tanka poems, an ancient style of poetry typically translated into five lines in English, although no line breaks were typically present in the original Japanese, at least not in terms of how most European languages write poetry. She began publishing early, in high school, and her first collection of poetry came out in 1901. Midarigami, which is usually translated as Tangled Hair, although Disheveled Hair is a little closer to the true meaning, remains her most widely known work, although she also produced several other volumes and a new translation of The Tale of Genji. Yosano's work was far more sensual and sexual than most women poets at the time – she's largely credited with being the first female poet to use the word “breasts” in a sexual context – and it made a large impression on the writing world, particularly women. The title itself has a very sensual connotation – rather than meaning “tangled” as in “unbrushed and snarled,” midarigami is meant to evoke the image of a few stray hairs brushing the nape of a woman's neck as they escape from her neat up-do; her sexuality unable to be bound by propriety. This, along with her career of helping women writers to get their start in publishing and her passion for equal rights, is probably the biggest contributing factor to how Yosano is portrayed in the show. While she is clean-cut in appearance, with a slightly messy bob and a skirt that goes to her knees, she is also the show's version of the “sexy nurse” trope – her gift is “Thou Shalt Not Die,” a healing ability. The wispy quality of her hair is clearly a reference to Midarigami, and the use of the aforementioned trope is likely due to the sensual nature of her poetry. It isn't a perfect match, but it does evoke a modern version of the sexuality she has come to represent.

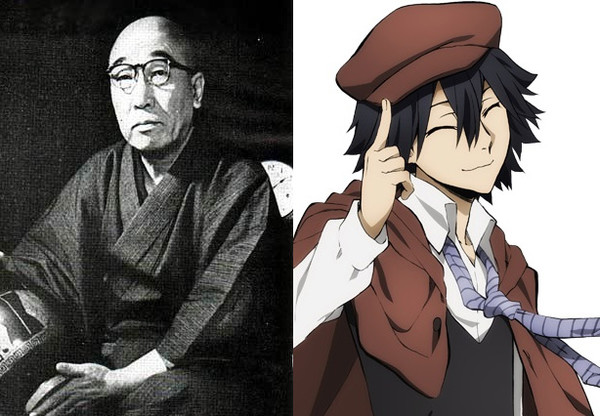

There's a much easier transition between reality and fiction for Edogawa Rampo, one of the authors a bit more known to western readers. While we only have a fraction of his works available in English translation, that's still a sizable chunk of his bibliography and substantially more than almost any other author represented by Bungo Stray Dogs. Born Tarō Hirai in 1894 and dying of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1964, his pen name is a tribute to the father of the mystery genre, Edgar Allen Poe, and Rampo himself is known as the grandfather of Japanese mystery. His works are divided between what one critic calls “tales of mystery” and “tales of imagination,” a reference to his short story collection Japanese Tales of Mystery and Imagination, and while Ranpo Kitan: Game of Laplace used both categories liberally, Bungo Stray Dogs' seems more interested in his mysteries. References are thus far at least twofold for Rampo – his gift, “Super Deduction,” is a wink and nod to the detectives of early mystery novels in both English and Japanese, quirky men with limited social skills who had amazing detective skills that beggar belief, while a subgroup of the villains of the show, the Port Mafia, are named after one of Rampo's most famous bad guys, mysterious and sexy lady thief The Black Lizard. In the show, Rampo's character design seems to evoke another of his most famous characters, the boy detective Kobayashi, who first emerged in 1930. Rampo's outfit bears a definite air of a boy of the 20s and 30s, while his attitude is much more like Akechi Kogoro, the detective Kobayashi assisted. The twist on Rampo's gift is also a nod to his fictional detectives: while Akechi and Kobayashi solved many cases together, some of them really weird, none of them relied upon supernatural means of detection or by way of explanation; they were all very human crimes. So when we learn that Rampo's gift is actually all in his head and he's really just a spectacular detective, it seems to bring us back to that base tenet of true mystery fiction: a supernatural skill or explanation is the worst sort of cop out. (For more on Edogawa's works, check out this editorial.)

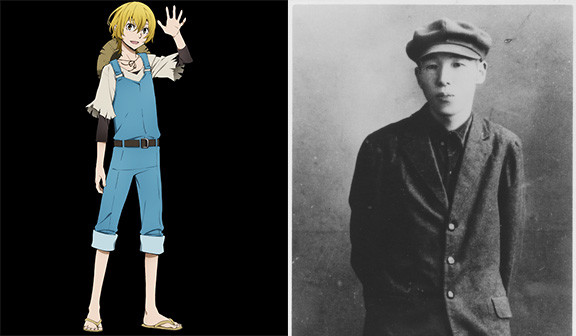

Like Edogawa Rampo, many of Kenji Miyazawa's works have also been translated into English, but with children's literature still considered something of a stepchild to “real” literature, there hasn't been as much study of them as there could be. (Most great works of children's literature have been co-opted by adults for university classrooms rather than given to actual children to read.) Miyazawa is one of the sad cases of Bungo Stray Dogs – like more than half of the authors represented, he died young, of pneumonia at age 37 in 1933. His stories weren't highly regarded during his life, but he has found posthumous fame as both a poet and a children's author. More anime viewers are likely to know his tale Night on the Galactic Railroad as both a frequently referenced title and as having received an anime adaptation of its own, and its beautiful simplicity seems to be part of the inspiration behind Miyazawa's depiction in Bungo Stray Dogs. Miyazawa himself was from a rural area, and his anime counterpart plays that up, appearing like an anime version of Mark Twain's Huck Finn, with overalls, a straw hat, and no shoes. While it is entirely possible that this is meant to evoke Twain's iconic child characters, it also serves as a reference to the hero of Night on the Galactic Railroad, a rural child living in poverty. Miyazawa's gift of superstrength, “Undefeated by the Rain,” again calls to mind the trials weathered by both the author and his characters – the gift can only be activated on an empty stomach, with its name proving that nothing can get him down, not poverty, not starvation, and not the whims of nature. Like real-life Kenji Miyazawa's works, neglected during his lifetime, this character will survive and be recognized. (So far at least…)

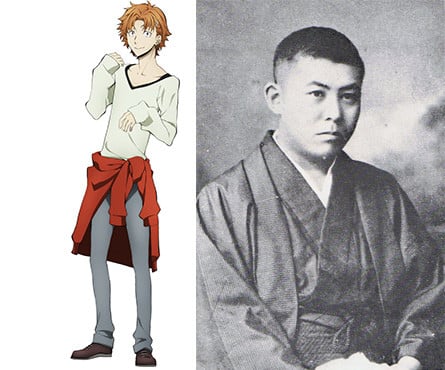

On the opposite end of the spectrum from real-life Miyazawa, we have Jun'ichiro Tanizaki, an author nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Among scholars and fans of modernist fiction, which largely deals with a sense of cultural dislocation in a rejection of 19th century literary norms, Tanizaki is very well known, much in the same way that most people know who Virginia Woolf is, even if they haven't read her books. Before his death at age 79 in 1965, Tanizaki produced a substantial amount of work, from novels to essays to silent film scenarios. (“Scenario” is the term for a silent film script rather than just the idea behind one.) His books ran the gamut from overtly, and in some cases unsettingly, sexual to much calmer fare, with one of the standouts being 1924's Naomi. As a novel, Naomi explored questions of Westernization and whether or not East and West could find a meeting or melding point in terms of culture, a topic also explored by Pearl Buck in her novel East Wind, West Wind from 1930. The character of Naomi was said to have been inspired by Tanizaki's step-sister, which may explain why his fictional incarnation has been given a younger sister named Naomi who seems to have a romantic attachment to her brother. Not only does this make for a pretty funny reference to the novel, but it also nicely encapsulates some of the more uncomfortable themes in some of Tanizaki's works, while also managing to use one of the more popular anime tropes of recent years. (As a fun fact, the administrative assistant for the Armed Detective Agency we most often see, Haruno, is also named after a character in Naomi.) His gift, “Light Snow,” is a more sedate reference to his prowess as a writer, with its invocation not only creating snowfall but also projecting illusions onto it. We can see this as being a solid representation of his gift for writing vividly but gently, which is something I associate even with his more explicit works. Every author wants to be able to make you really visualize what they're describing, and Tanizaki had the talent to pull it off. “Light Snow” is a physical manifestation of his great literary skill, a deceptive quietness that pulls you into his world before you know it's even happening.

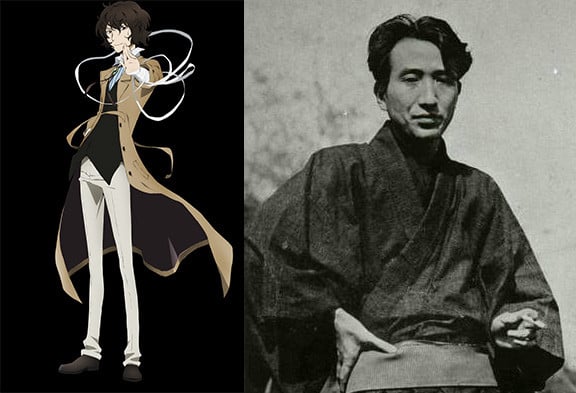

Not as famous in translation but more central to the plot of Bungo Stray Dogs is Doppo Kunikida, a romantic poet and naturalist novelist. Another of the tragic figures of real life, Kunikida died at age 36 of tuberculosis (sometimes called consumption), though not without leaving behind a decent amount of both poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. In fact, he's credited with basically inventing the Japanese form of naturalism, an off-shoot of realism that, simply put, bases its stories on the theory that you cannot escape the circumstances into which you were born. (The best example I can think of is Stephan Crane's Maggie: A Girl of the Streets.) Kunikida's story “Gen Oji” is considered his best example of his blending of romantic poetry (he loved William Wordsworth) and naturalism, and while his sensibility might not seem particularly unique today, it certainly was when the story was published in the late 1890s. Kunikida's life was eventful, marked by divorce, poverty, and social rebellion, including conversion to Christianity. Interestingly in the context of Bungo Stray Dogs, the only possible way for his protagonists to escape their allotted fates was to commit suicide, and while Kunikida himself never did his first wife's mother encouraged her to do so rather than marry him. How the idea of suicide conflicted with his new religion (Christianity considers suicide a sin) isn't entirely clear, but it makes for an interesting context within the show, particularly in terms of his in-show partner, Osamu Dazai. Speaking of the show, Kunikida's strict and serious nature reflects the naturalistic themes in his work, while his gift, “Doppo Poet,” grants him the ability to create physical manifestations of words. This may be a nod to the fact that naturalism is considered realistic fiction, the implication here being that his words are so real that they can, in fact, be turned into usable objects. In any event, he's clearly got the most practical ability of the bunch and the maturity not to abuse it.

Osamu Dazai, on the other hand, spends his time in the show bouncing between “humorous” suicide attempts and explaining things to our point-of-view character, Atsushi Nakajima. He's the most outwardly, or superficially, lighthearted character, which may leave a bad taste in some viewers' mouths when you consider the real-life author. The root of all of those suicide jokes is that Dazai tried multiple times to kill himself, beginning in 1929 at the age of twenty he attempted suicide via an overdose of a drug called Calmotine. It is largely thought that he was influenced by the suicide of his writing idol, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, who killed himself via overdose in 1927, since the news of Akutagawa's death severely affected young Dazai. In 1930 Dazai again overdosed on Calmotine, this time with a woman, Atsumi (or Shimeko; sources disagree on her given name) Tanabe – he survived, but she did not. Five years later, he attempted to hang himself, and a year after that, having survived an addiction to morphine, he and his first wife Hatsuyo attempted double-suicide via sleeping pill overdose after he caught her cheating on him. This attempt also failed, and after surviving tuberculosis and alcoholism, he finally succeeded in killing himself in 1948 – he his lover Tomie Yamazaki committed double suicide by drowning themselves in the Tamagawa Canal.

Considering this history, the decision to play off Dazai's suicidal urges as a joke can feel insensitive at best, and very tasteless at worst, especially since today we can look at his life story and understand that he was likely suffering from a mental illness. (Although coping with a difficult topic by making jokes is also a way we can view this.) The fact that his gift, “No Longer Human,” is a nullification power that stops others from utilizing their abilities, can also be seen as a reference to his quest to end his life alongside someone else (you'll notice that three of his attempts were “shinju,” double suicides, something he keeps trying to convince women to do with him in the show), as well as being the title of his best-known work, which details the downward spiral of its protagonist. While Bungo Stray Dogs' incarnation of Dazai is delightful, it is also the most troubling in terms of how it spins his real story into its fictional one, no matter how understandable the choices may be on the surface.

The final author I'll discuss is our aforementioned point-of-view character in the show, Atsushi Nakajima. Another of the authors to die tragically young – pneumonia in 1942 at the age of 33 – Nakajima published relatively few works, although they were all well received. Something of an existentialist and a fan of both Robert Louis Stevenson (about whom he wrote a story) and Franz Kafka, author of the infamous work The Metamorphosis. If you've seen the show, you can probably guess where this is going – Nakajima's best known work, “Sangetsuki,” is considered his answer to Kafka's novel, and features a man who transforms into a tiger. And what is Nakajima's gift in the show? Why, yes – he can transform into a tiger himself. This is one of the rare cases in Bungo Stray Dogs where the connection is so perfect, and I do have to wonder if it was the inspiration for the entire story. In any event, it is thanks to “Sangetsuki” that Nakajima's works have not been forgotten, as it is a common inclusion in Japanese textbooks. The story deals with inspiration and aspiration turning its hero to madness, which is a definite risk for the show's Atsushi as he tries to find his place in life after having been booted out of the orphanage he was living in and now having to find a way to assimilate into the Armed Detective Agency. When he first appears in the story, he can't control his gift, so he must learn to harness it and make it bend to his will. Admittedly this is more of a modern literary conceit, particularly when it comes to urban fantasy about werebeasts, but it does stay in line with Nakajima's existentialist themes, as well as his fascination between oral and written communication, which it could be argued are reactive and planned, respectively – which is what Atsushi is trying to make the switch between with his powers.

And there you have it – some of the real authors behind the characters of Bungo Stray Dogs. There are of course many more, and if you continue to look into them, you will find that many died young – Chuya Nakahara died at age 30 of cerebral meningitis, Ichiyō Higuchi at 24 and Motojiro Kajii at 31 of tuberculosis, and Ryūnosuke Akutagawa killed himself at age 35. Given these high numbers, I like to think that Bungo Stray Dogs exists as a chance at giving these too-soon departed authors a second shot at life, albeit a very different one. Whether or not this holds true, it does make for interesting background knowledge about the Armed Detectives and their rivals in the Port Mafia. We'd love to hear your thoughts about them in the forums.

discuss this in the forum (14 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history