Brain Diving

Up and Atom!

by Brian Ruh,

We all have secrets – dark parts of ourselves we feel compelled to keep hidden from public view, ever nervous of the consequences should anyone find out. I have some very geeky secrets, and I'm sure you probably do too – for example, movies and shows we can't stand (or worse, haven't seen) yet pretend to like. So I'll let you know one of my secrets: I've never been a big fan of Osamu Tezuka.

How can this be? In addition to being a prolific manga artist and animator, Tezuka was a great storyteller and created many science fiction tales. And of course I'm a big SF fan – take for example, as mentioned last week, the name of this column. So shouldn't I be going around singing Tezuka's praises, thankful that an ever-increasing number of his manga and anime titles are being released in English? What do I have against Osamu Tezuka, who is often called the “god of manga”?

I have read many of his works, and although I know I'm just scratching the surface, there hasn't been a single one that I've disliked once I got into it. Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atom) is a seminal work of science fiction in both Japan and abroad. I found his MW manga to be dark, complex, and engaging. The complete set of his hardcover Buddha manga occupies a special place of honor on my manga shelf, and I'm quite fond of his animated short Jumping. So it's certainly not that I dislike Tezuka's stories.

As someone interested in the history of manga and anime, I can appreciate the special contributions he made to the art forms. His manga really helped to popularize comics for all readers and he pioneered the television market for domestic animation in Japan. In spite of all of this, I've rarely felt compelled to seek his stuff out. I'll admit that part of it is superficial – the “cartoony”-ness of his style never really grabbed my attention like some other manga artists with a more detailed, grittier style. But I've often felt that I should like Tezuka more than I do, that there might be a basic part of his manga that I'm just not getting.

This is why I was interested in readying Helen McCarthy's new book on Tezuka's life and works. I figured that if anyone could get me to appreciate Tezuka's works more fully, it would be her. Helen has been writing about anime and manga for decades – surely she could give me the kick to go out and buy some more Tezuka books. I figured now would be a great time to talk about the book, since it recently won the Harvey award for “Best American Edition of Foreign Material,” beating out, among other titles, Pluto by Naoki Urasawa, which is an take on one of Osamu Tezuka's original Astro Boy stories.

Before I talk some more about Tezuka, though, I'd like to discuss a bit of other manga history in this week's Read This!

Before I talk some more about Tezuka, though, I'd like to discuss a bit of other manga history in this week's Read This!

I was doing some manga research earlier this week (yes, this is really what I do for fun in my free time) when I came across an electronic reprint of the 1960s and ‘70s magazine Concerned Theatre Japan at the University of Michigan. You might be wondering what theater and manga have to do with one another, but there are some definite connections. For example, as McCarthy explains, Tezuka grew up in the city of Takarazuka, home of the famous Takarazuka Review – an all-female musical theater group. Tezuka incorporated many elements from the Takarazuka into his manga, and later in his career the troupe in turn performed stage adaptations of some of his manga. At the time that Concerned Theatre Japan magazine was being published, there were quite a few crossovers between manga and theater in the Japanese artistic underground.

A great example of this is in issue 2.1 of the magazine, in which playwright Saito Ren discusses his play Red Eyes, which was adapted from a Sanpei Shirato manga, and goes into a bit of detail about what manga is and the role it plays in Japanese society. Keep in mind that this issue came out in 1971, before there was any manga fandom or much knowledge of what manga really was outside of Japan. And he has some high praise for what Tezuka had accomplished even at that time, saying “it was with Tezuka Osamu that Japanese comic books first ceased to be the opiate of the young and entered the realm of Culture.” If you're just interested in the manga itself, you may want to skip to issue 2.2 of Concerned Theatre Japan, which contains translations of Sakura Illustrated by Genpei Akasegawa, Red Eyes by Sanpei Shirato, and The Stopcock (Neji-Shiki) by Yoshiharu Tsuge. These are all rather political manga from the 1960s, reflecting the tumultuous nature of the times, and as far as I can tell they were the first manga that had been translated into English.

As McCarthy explains in her book, such manga are also examples of the more adult, worldly comics that Tezuka had to contend with in the 1960s. Such manga, McCarthy writes, “appealed to readers who felt they had outgrown the comics of their childhood” (aka Tezuka's manga). It's easy to see something child-like in Tezuka's rounded, cartoony designs, especially when compared to the edgy grit of an artist like Sanpei Shirato. And I have to admit that's part of what gets me, too – even though I know better, Tezuka's designs always struck me as a bit juvenile.

But wait a second – I was going to try to learn something, wasn't I?

The Art of Osamu Tezuka

The Art of Osamu Tezuka

The first thing that struck me about Helen McCarthy's book is how significant it is – I first noticed it prominently displayed on an end cap at a chain bookstore, and it certainly has presence. It's a large, hardcover book with bold lettering and a single image of Astro Boy on the cover. It's enough to grab your attention from across the store, and its use of Astro Boy could be geared toward getting the attention of readers who may not be in to contemporary manga.

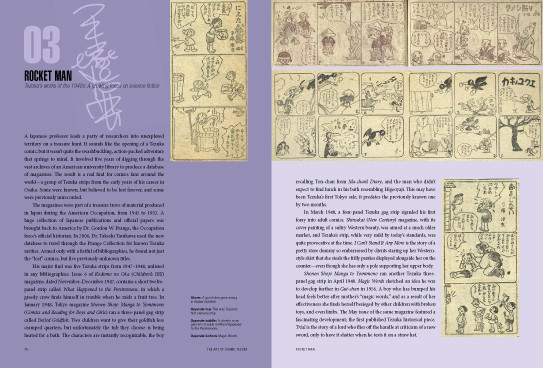

The heft of the book really makes it “at home” reading, though. This isn't the kind of thing that you're going to just throw in your backpack and read in your free time. It's actually something of a shame, since McCarthy's prose is divided into accessible chunks, each one relatively self-contained. It would make for good reading to pick up here and there if only the book wasn't so awkward to lug around. However, the book is wonderfully illustrated throughout with multiple images on each page, so a lot can be forgiven in terms of its format.

One of the things that McCarthy laments at the beginning is that Tezuka seems to be more well-known by academics than by general readers. I think to a certain extent this is true – pretty much anyone who studies manga knows the basics of Tezuka and his life, yet his works occupy a relatively small space on contemporary manga shelves. (Although I wonder if the same thing could be said to be occurring in Japan as well? It's been far too long since I've been able to go to Japan and browse around a bookstore.) It's pretty easy to see why academics might be attracted to Tezuka – with his takes on literature like Goethe's Faust and Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment, as well as religious tales like Buddha, Tezuka's manga seems perfectly primed for some high-culture analysis. However, as McCarthy points out, although Tezuka was well-read, he made his work for the masses and didn't talk down to his audience. The many academic works on Tezuka could lead people to think of his manga as eggheaded intellectual exercises rather than the popular works they were. McCarthy sees her book as a step to try to remedy this and to build further interest in the man and his manga.

It's quite an ambitious attempt to encapsulate Tezuka's life and work in a single book, yet McCarthy pulls it off remarkably well. Tezuka's life and works are presented in chronological order by decade. The first chapter briefly covers his life from birth until his manga career begins to take off, at which point McCarthy detours to detail Tezuka's star system, which was his technique of thinking of his characters as actors outside of the roles they were playing so he could reuse them throughout his works. McCarthy then devotes a chapter to each decade from the 1940s through the 1980s, highlighting Tezuka's major works and accomplishments. She concludes with a chapter each on the works he left unfinished and the legacy he left behind following his untimely death from stomach cancer in February 1989.

The book also comes with a bonus DVD, which I kept forgetting because it's not referenced in the text of the book itself. Labeled “The Secret of Creation,” it is a 45 minute NHK special that follows Tezuka for a few days in 1985. It begins by showing his modest working private space in a nondescript housing block in Tokyo and follows him through his hectic schedule of manga deadlines, travel, and working on animation. Although Tezuka laments the onset of age, noting that he can no longer draw circles freehand the way he used to be able to, he demonstrates a strong vitality in spite of all of the pressures placed on him and says that he has many ideas for new manga projects. In one scene toward the end of the special, Tezuka notes the clock and says that he wishes he just had more time – he is referring to one of his many looming deadlines, but for the viewer this is a particularly poignant remark as we know that Tezuka was to live for only four more years after the special was taped.

McCarthy also doesn't shy away from addressing some of the controversies surrounding Tezuka's legend. Tezuka is commonly seen as the man who brought a modern visual language to manga by incorporating many techniques that he originally saw in the movies. (Tezuka was an avid cinema buff throughout his life.) Even though Tezuka popularized these techniques, and was certainly revolutionary in his own way, he wasn't the first Japanese comic artist to try such things. Additionally, Tezuka has been knocked for, in a manner of speaking, being too popular in Japan. McCarthy mentions Go Ito's book Tezuka is Dead for its criticism of how Tezuka has emerged as the central figure in postwar manga, as if all Japanese comic art in the late 20th century was filtered through the man. This perspective overshadows the many lesser-known artists both before and after Tezuka who made significant contributions to manga. For McCarthy, though, while such “debates about his influence are less important than experience of his works.” More than anything, McCarthy seems to want people to just read more Tezuka.

I'm happy to say that I did learn quite a bit from The Art of Osamu Tezuka. Of course I knew some of the highlights of Tezuka's career, but there was a lot that I wasn't aware of. I also hadn't paid particular attention to when some of the Tezuka manga I had read were written, so I didn't know how they fit into the man's overall body of work. McCarthy's book certainly helped me to get a better perspective on Tezuka, but more than anything else the large, full-color illustrations whet my appetite to read more of his manga. I learned about quite a few titles that I'd love to see in an English version. (Barbara, which McCarthy describes as “sexually charged and profoundly disturbing,” in particular seems like something I'd want to read.)

However, I keep going back to McCarthy's mention of Tezuka is Dead. I have to agree with Go Ito here – Tezuka was undeniably important to the development of postwar manga, but the development of popular manga was far from a solo effort. The question of influence may be an academic question, but since I consider myself of scholar of anime and manga, stuff like this is important to me. I can't help but wonder if a book that calls Tezuka the “god of manga” right on the cover isn't still contributing to Tezuka's legend while further obscuring some lesser-known artists. (For example, I'd love to see more works like Manga Zombie published in English.) On the other hand, a more thorough appreciation of Tezuka is probably necessary to fully understand the history of manga and anime, and we're not even close to getting the man's entire body of work translated into English. If this book encourages anyone to go out and pick up some Tezuka, or if it encourages more companies to bring out other Tezuka works, I think we should probably count it as a victory.

Brian Ruh is the author of Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. You can find him on Twitter at @animeresearch.

discuss this in the forum (10 posts) |