Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | ||

|---|---|---|---|

horseradish

Subscriber SubscriberPosts: 574 Location: Bay Area |

|

||

|

Hmm, a person named 馬島 巽 was the production manager, possibly read as Tatsumi Majima in Western name order. Probably supervised production and not the actual staff though. I know little about the production process in general, especially methods used in the '60s, so someone more knowledgeable would have to chime in.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girls index

**** Splash of Crimson #2, Françoise Arnoul (aka Cyborg 003)

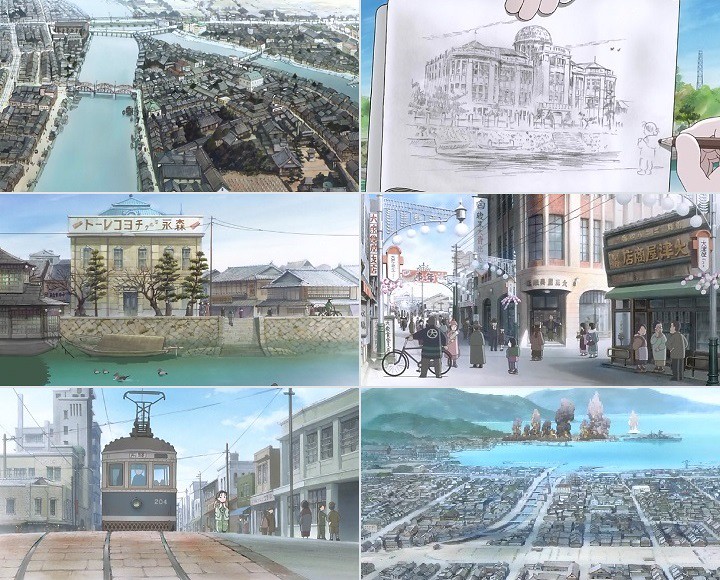

Françoise darts out from a gun battle to powder her nose before returning to the fray. Patronising? Subversive? You decide. Cyborg 009 Synopsis: Following on the from the defeat of the Black Ghost in the two earlier films (reviewed here) the nine super-powered cyborgs have, mostly, returned to their native countries where they uphold the values of the team. A core group remains with their creator Dr Gilmore in Japan to fight evil whenever it appears. In a cold-war world, though, villainy can cross borders and oceans, so the cyborgs are always available to lend each other a hand. For extreme international crises - such as a nuclear ICBM shoot-out between two superpowers - the full team will come together to save humanity. Production details: Premiere: 05 April 1968 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #3 Princess Knight and Beautiful Fighting Girl #4 Secret Akko-chan). Director: Yugo Serikawa (Anju to Zushio Maru, Cyborg 009 movie, Cyborg 009: Monster Wars, Mako the Mermaid) Studio: Toei Source material: the manga Saibogu Zero-Zero-Nain by Shotaro Ishinomori, in various magazines, July 1964 - 1981 Script: Masaki Tsuji (Astro Boy, Kimba the White Lion, Sally the Witch, Secret Akko-chan, Mako the Mermaid, Majokko Tickle, Urusei Yatsura among many others), Masaru Igami, Hiroshi Ozawa, Junnya Sato, Susumu Takahisa, Toyohiro Ando, Yugo Serikawa Music:Taichiro Kosugi Note: Although I was able to track down all 26 episodes, only 15 had fansubs (1-14 and 16). I watched the others raw. I'm hoping this is the last time I'll be watching raw episodes. Comments: In this update of the Cyborg 009 franchise Toei and Ishinomori further tweak the squadron / cyborg formula while retaining the 1960's charm of its predecessors. Compared with Rainbow Sentai Robin the squadron has grown in size and character range, the action has become more terrestrial, the backgrounds less fanciful and the subject matter more in tune with the era's Cold War shadow. The series forgoes the colour of the two movies - Cyborg 009 (1966) and Cyborg 009: Monster Wars (1967) along with some of their hyperbole. Don't worry, there remains much of the silliness that was a feature of the older series and films. This first Cyborg 009 TV series has its share of goofy moments and regular goodie v baddie plot lines, but from time to time it throws up episodes with a level of sophistication unexpected from Toei. I'll come to them shortly. This iteration of Joe Shimamura is softer, more feminine looking than his appearance in the films. In my review of the Cyborg 009 films I argued he was a template for anime protagonists for the next two decades and listed several examples of the lineage that follows (Koji Kabuto from Mazinger Z can be added to the list). Having now watched Rainbow Sentai Robin I can now see how Joe is an updated version of Robin. Of course, Joe is a cyborg, which makes him a little stranger and thereby more interesting, but, paradoxically, he has a less remote personality and thereby is also more appealing. As mentioned in the Rainbow Sentai Robin review above I was strongly reminded of the wartime depictions of the peach boy, Momotaro. You could see Robin and Joe as links between the historical Momotaro and the archetypal anime hero.

Top: Joe Shimamura / Cyborg 009 in action mode. Middle (l-r): Françoise Arnoul / Cyborg 003  ; Ivan Whisky / 001 ; Ivan Whisky / 001  ; Doctor Gilmore; Albert Heinrich / 004 ; Doctor Gilmore; Albert Heinrich / 004  ; ;

Chang Changku / 006  ; Pyunma / 008 ; Pyunma / 008  ; Sir Great Britain / 007 ; Sir Great Britain / 007  ; Geronimo Jnr ; Geronimo Jnr  ; Jet Link ; Jet Link  ; ;

and Joe Shimamura  . .

Bottom left: perhaps the first anime resurrection of IJN Yamato. Bottom middle: a flying saucer absconds with the top half of Tokyo Tower. Bottom right: African independence leaders from the best episode of the series. After Joe and Françoise the most important characters are Chang Changku / 006 and Sir Great Britain / 007. Respectively a fire-breathing cook and shape-changing waiter at a Chinese restaurant in Tokyo, they fill the usual Toei comic relief roles and, like other similar Toei characters, they haven't transitioned well into the 21st century. In short, they severely tried my patience. As in the films Sir Great Britain is a juvenile, presumably to appeal, along with Joe himself, to the target audience of young boys. Shotaro Ishinomori wasn't happy with the change from his manga. I don't blame him. The super powers of the cyborgs are intentionally ridiculous. They include super intelligence and psychic powers (001 / Ivan Whiskey), rocket-powered flight (002 / Jet Link), an arsenal of weapons (004 / Albert Heinrich), armoured skin (005 / Geronimo Jnr), and mechanical lungs for underwater breathing (008 / Pyunma). The abilities in combination makes the squadron effectively invincible, so the series is rarely suspenseful. Instead, beyond the goofy humour and exaggerations, to this older viewer from another century, the appeal or otherwise of Cyborg lay in the subject matter of the individual episodes. Interest was minimal, despite the underlying cold war analogies, whenever an episode fell back on the standard narrative formula of the cyborgs fighting and, of course, defeating villains, be they aliens, mad scientists or dictators. Only when the anti-war, anti-colonialist and anti-nuclear weapon themes became explicit does Cyborg 009 step beyond its demographic limitations. In episode twenty, the cyborgs intervene in the Nigerian Civil War (1967-70) to protect two civil rights leaders from assassination. The allusions to the civil war and Martin Luther King Junior are remarkable. In episode sixteen a crazy scientist, still grieving a son killed in World War II, has created a machine that can restore the sunken Japanese warships and planes from the floor of the Pacific Ocean. Leading with the now invinicible IJN Yamato, he wages war against America. This may be first instance in anime of the resurrection of the great ship but, unlike the romantic myth building of Space Battleship Yamato, the wishful thinking of KanColle or even the ambivalence of Zipang, the episode doesn't hold back with its anti-war sentiment, being at once a satire on the Japanese militarist right and a plea for peace. As the professor rants, we see images of the Hiroshima Peace Park. The site of the atomic bomb attack is revisited in the last episode as two nuclear armed superpowers, under the influence of a malignant alien who has taken the disturbing guise of a leering female doll and whose chilling voice brings to mind both Kerbero and Kyubey, unleash armegeddon upon the planet. Unsubtle, like everything else in the franchise, but very effective. Some Japanese PTA groups questioned the appropriateness of the anime's subject matter for the demographic - particularly the atomic bomb references - leading to the broadcaster asking the studio to tone down the content. Instead the creators opted to end the series after 26 episodes. Visually the series doesn't match the quaint appeal of Rainbow Sentai Robin nor is it in the same class as Mushi's near contemporary Princess Knight, even making allowances for its black and white photography. For much of the run the characters follow the American tradition of having only three fingers (and a thumb) on each hand. As my screenshots reveal, the backgrounds are basic. But, then, Toei kept afloat as Mushi went under. The music is highly effective with an assortment of classical pieces, originals from Taichiro Kosugi and borrowings from the Toei catalgue. My favourite is a plaintive piece that has me wracking my brain to remember where I've heard it previously. Where would life be without unanswered questions?

A beautiful fighting girl has so many responsibilities. Françoise Arnoul: Tamaki Saito's Splash of Crimson archetype, Françoise's martial activities are expanded from the two films. Mind you, she takes until episode six before she fires a gun. She even repeats her missing-in-action effort of the climactic melee of Cyborg 009: Monster Wars. Perhaps she spends so much time doing her make-up so as to be the beautiful fighting girl (see top image) that she misses out on the action? More than anyone else in the squadron she has multiple roles. Her super eyesight and hearing make her indispensable and, as the series progresses, she participates more actively in the gun fights. Still, she does the cooking and serving, cares for the child cyborgs and, in her spare time, performs as an acclaimed ballerina. Yep - she's a supermum of sorts, juggling all manner of responsibilities. The important thing, though, is that no one doubts her abilities: everything she does, she does well. I suppose having a high-tech artificial body helps. Nor is she afflicted with cliched gendered hysteria or learned incompetence. Given her pivotal role in the development of the beautiful fighting girl I'll revisit the franchise at every opportunity. The regular remakes may shed some light on how representations of women in anime have changed over the last fifty years (the series anniversary was just over a week ago). Rating: so-so. The themes explored in the better episodes lift this above the previous Ishinomori adaptations, even with its black and white production. There's no getting around the poor designs and artwork and the more-often-than-not lacklustre episodes. Just the same, in two films and two TV series (including Rainbow Sentai Robin which is set in the same universe) over a period of 26 months, Shotaro Inishomori influenced anime in ways few others have managed. He bequeathed to us templates for male protagonists, beautiful fighting girls, cyborgs and squadrons of fighters. Resources: Cyborg 009 Wiki ANN The font of all knowledge The Japanese font of all knowledge Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press The last word:

Last edited by Errinundra on Thu Jul 22, 2021 4:07 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

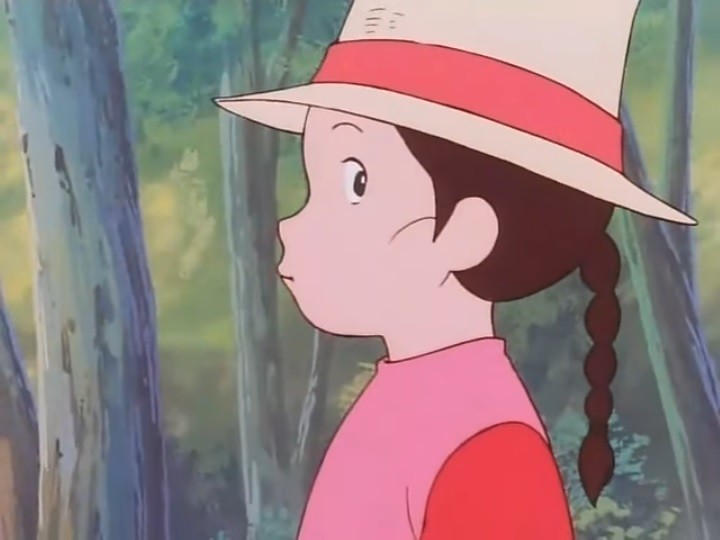

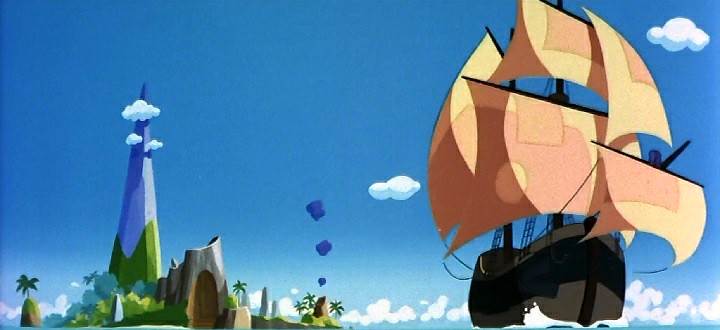

Splash of Crimson #3, Kathy Flint

Animal Treasure Island Synopsis: With a map bequeathed by an ill-fated cat pirate and his home trashed by henchman in the employ of the porcine Captain Silver, Jim Hawkins sets sail in a barrel in search of treasure. En route he teams up with pirate girl Kathy - the granddaughter of the very Captain Flint who buried the treasure and drew the map. The two must contend with shiploads of pirates without principles and unravel the secret of Treasure Island. Production details: Premiere: 20 March 1971 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #6 Mako the Mermaid and Beautiful Fighting Girl #7 Wandering Sun). Director: Hiroshi Ikeda Studio: Toei Source material: Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. Script: Hiroshi Ikeda and Takashi (ANN & 500 Essential Anime Movies) or Satoshi (The Anime Encyclopaedia) or Kei (Wikipedia) Iijima. Idea consultant: Hayao Miyazaki, who also provided key animation and scene design. Art Director: Isamu Tsuchida Animation Director: Yasuji Mori Music: Naozumi Yamamoto

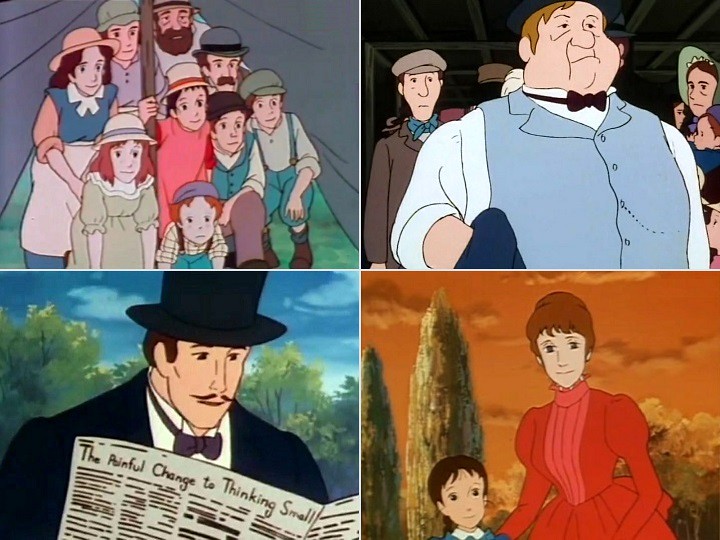

Captain Silver and his nefarious crew. That's Baboo peeking over the walrus pirate's shoulder. Comments: I first watched this via a fansub not quite five years ago when I was exploring early Toei films. It remains my favourite among them, thanks in part to Kathy, Hols - Prince of the Sun notwithstanding. I've since imported the Discotek release, so this review is based on that version. (It won't be the last Discotek review either - there's more to come in the near future. They are turning out to be a valuable resource for this survey.) Animal Treasure Island takes considerable liberties with the original novel, not the least being how all the characters other than Kathy, Jim and his younger brother Baboo are animals. The effect of this is to render comical the considerable amount of violence on screen. It also means that the activities of the two obligatory Toei diminutive characters - Baboo and Glan the mouse - aren't nearly as jarring as their counterparts in earlier films from the company. In other words, this is one of the few instances where Toei strikes an effective balance between drama and comedy. Don't forget, though, that this is a family film, so don't expect a lot of sophistication and do expect considerable corniness. At least we don't get animals singing, although there's a excruciating ode to adventure and bravery sung by a children's chorus. On a brighter note there's a contrasting, devilish ode to the joys of theft, murder and mayhem sung by a male chorus (Oh yes! So so!). Crew members later upstage even this with a sort of klezmer tango to entice Kathy from her cabin. When that fails Captain Silver - he's a pig - does an athletic dance routine to a brassy big band number while she looks on in disbelief. It's all done at a brisk pace, with constant activity, plenty of, again corny, sight gags and, again violent, fight scenes. It has a verve missing in other Toei films. Jim Hawkins is a straight-ahead, determined, all-action, no-thought protagonist along the lines of Hols or the titular character from Future Boy Conan, though with a somewhat more comical emphasis. I smell Hayao Miyazaki's input into the production. All the same, like everyone else in the movie, he wants the treasure, and he's willing to kill his rivals, or even leave his supposed ally, Kathy, in the lurch (see images below), to get it. If we accept him as more moral than the pirates it would be due to his youthful, optimistic personality and his loyalty to Baboo, Glan and, later, Kathy. There isn't a skerrick of loyalty or honour among the pirates. Every last one is prepared to double-cross the others. Well, maybe not: there's a walrus who takes a shine to Baboo and who is something of an exception that proves the rule.

Speaking of honour and pirates, when Jim meets Kathy in a slaver's holding cell, he discovers that she's the granddaughter of Captain Flint, the former owner of the plundered treasure. When she insists that she is now its rightful owner, Jim expresses his disgust with all pirates, to which she responds indignantly, "How dare you say that about my grandpa... He was an honourable pirate." Now, please hold that thought for a moment. Captain Silver, as with the original Long John Silver, is a much more compelling and larger-than-life character than Jim or Kathy. Of course, he's totally bad, what with his greed, his recourse to violence to solve problems, his gigantic ego and his equally boundless treachery, yet he has a gleeful swagger, a braggadocio that has him dominating his confederates and, more often than not, the film. I suppose swashbuckling is the word people would use. From time to time, I found myself uncannily reminded of Porco Rosso, as if the two were twins separated from birth. Obviously, of the two, Silver fell into bad company. Again, I'm getting a whiff of Miyazaki. Now, add in the feisty girl's comment about honourable pirates and I'm left wondering if the germ of the idea for Porco Rosso was born in Animal Treasure Island in much the same way there are pre-echoes of My Neighbour Totoro and Ponyo in the Panda! Go Panda! films. Ah, speculating can be fun. Kathy: As the one and only female character in the entire film, I suspect she was added to both broaden the film's appeal and soften what is otherwise a macho affair. That said, there is little that is conventionally feminine about her other than she wears a dress. The quality I like most is her autonomy. She, not Jim, is the hero of her narrative. She has her own agenda - getting her hands on the treasure - and, initially, she doesn't want Jim's help to get it. The film's treatment of her isn't always so liberated: her first appearance is in manacles while she spends much of the climax trussed and buffeted. And, yes, Jim will save her. Like Jim, Kathy is resolute and loyal to her family - in her case, her pirate grandfather. She is also courageous under fire, on occasion leaving Jim in her wake as bullets fly about. Kathy is a modern heroine to Jim's more traditional hero. She also seems older and smarter, though in the sequence of images below he does a quite a number on her. Her major shortcoming as entertainment is a somewhat dour personality. It is worth noting that in the history of anime she predates such notable beautiful fighting girls as Fujiko Mine (Lupin III), Maetel (Galaxy Express 999), Oscar (Rose of Versailles) or Nausicaa (Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind). While not as interesting as any of them, Kathy is, nonetheless, ahead of her time.

What a scumbag! Jim nicks Kathy's cutlass mid-battle, leaving her in a precarious situation. The artwork is simple, angular, lacking in detail, yet brightly coloured and appropriate to the thematic material. It suggests a blending of 1960s Disney and Hanna-Barbera character designs - especially the animals - and backgrounds, thus seeming less authentically anime than Toei's own Cyborg 009. Toei were aiming for an international audience, after all. In the pirate song mentioned above the film quality dips, leaving me to wonder if the segment was sourced elsewhere. The colour palette changes, which is intentional, but the colour intensity becomes muted for no apparent reason. Perhaps the effect is deliberate but, either way, it detracts from the sequence. Rating: decent. A very loose, yet entertaining adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson's classic tale brings to the screen a regular male protagonist, a swaggering villain and a surprisingly autonomous heroine for her time. With its animal characters, bright artwork and corny humour Animal Treasure Island is intended for a young audience. That may be so, but the child in me enjoyed it thoroughly. Resources: ANN The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle 500 Essential Anime Movies: the Ultimate Guide, Helen McCarthy, Collins Design

Last edited by Errinundra on Thu Jul 22, 2021 4:07 am; edited 2 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

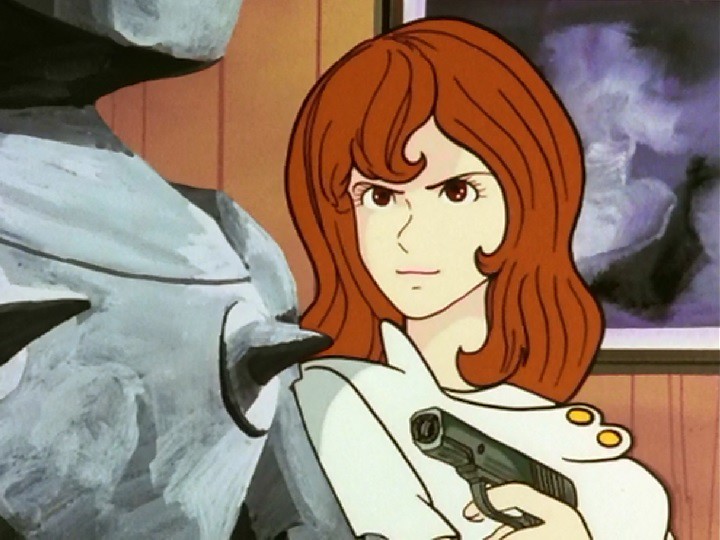

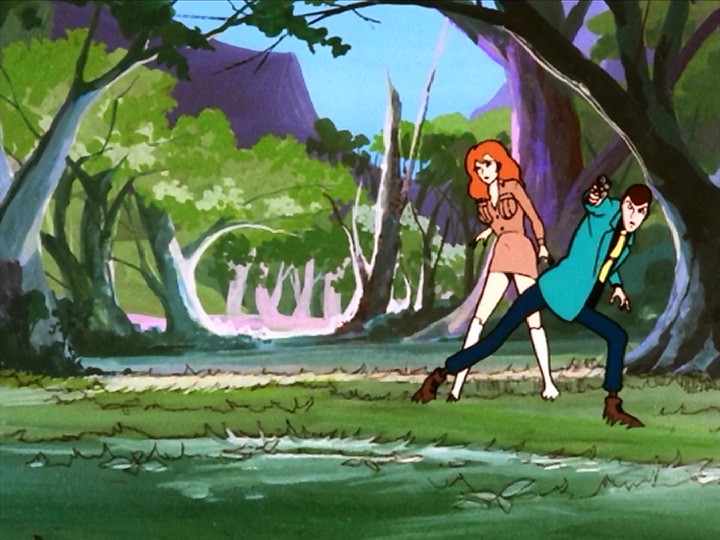

Splash of Crimson #4: Fujiko Mine

Lupin III (1971) Synopsis: Arsene Lupin III is a master thief who prides himself on his buglary skills and his quick-thinking. His loyal off-sider, the sharp-shooting Daisuke Jigen, is always on hand to help out in sticky situations, especially when femme fatale Fujiko Mine is out to relieve Lupin of his stolen goods, or when the Tokyo Police Department's finest, Heiji Zenigata, is hot on his trail. Also tagging along is swordsman Goemon Ishikawa XIII for whom loyalty to Lupin isn't always of paramount consideration. Production details: Premiere: 24 October 1971 (TV series, between Beautiful Fighting Girls #s 9 and 10 Sarutobi Ecchan and Chappy the Witch); 1969 (pilot film - not released) Directors: Masaaki Osumi, Hayao Miyazaki & Isao Takahata Studio: Tokyo Movie (later TMS) Source material: Lupin III by Monkey Punch (Kazuhiko Kato) in Weekly Manga Action, 10 August 1967 to 22 May 1969 Original concept: Maurice Leblanc Character designer and animation director: Yasuo Otsuka Music: Takeo Yamashita Background: The pilot film and the early episodes of the series - directed by a Masaaki Osumi - reputedly reflect more closely the tone of Monkey Punch's manga. The first two episodes rated poorly, so Osumi was asked to make changes. When he refused, the studio sacked him and appointed the more obliging Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. According to Wikipedia Osumi had complete creative control over episodes 1-6 and 9, while 7, 8, 10, 12 and 13 were a mishmash of contributions from all three directors, with the remaining eleven episodes lacking any input from Osumi. Comments: From episode 4 onwards Lupin begins proceedings by introducing the cast members as follows.

This, of course, is but an elaboration of my synopsis above, but the two highlight a core element of the series: a recurring narrative formula derived from the characters' established traits. An episode's success or failure thereby depends on the appeal of the characters themselves and whether the creators can pull off any surprises within the limitations of the repetitive structure. The eventual succes of the series - after the bumpy start it rated around 9% - and the longevity of the franchise indicate that Monkey Punch and the successive anime creators in his wake had at their disposal five personalities with sufficient scope, while retaining their signature traits, to allow a degree of invention. Beyond this series I've only seen Castle of Cagliostro and the eye-opening The Woman Called Fujiko Mine and, in each case, the directors made terrific use of the basic elements. This, being the first ever anime version, has the good fortune of tilling virgin soil and, for the most part, does so productively.

Clockwise from top left: Lupin, Goemon, Zenigata and Jigen - all in typical poses. The most notable thing, though, is the stark difference in tone and rhythm between the early Osumi episodes and the later Takahata / Miyazaki ones. Osumi brings a hippy come noir come insouciant sensibility. Lupin is seedier and arrogant, rather than simply self-confident. His facial design is harder, more smart-alecky. He looks more the criminal that he is. Jigen is taciturn, cynical and most often immobile yet giving the impression of being alert and poised to strike. From the get go, however, he is utterly loyal to Lupin. Fujiko, for her part, is heavily sexualised. Indeed, Osumi has his characters indulge in sex, though not on screen. In the pilot a naked Lupin even jumps a sleeping Fujiko. (He gets a foot in his face for his troubles.) The incidental music includes psychedelic styled pieces from composer Takeo Yamashita that adds to the late 60s / early 70s mood. I'm reminded of Osamu Tezuka's and Eiichi Yamamoto's Tales of a Thousand and One Nights, made just two years earlier. Like that film's main character (Aldin or Aladdin), Lupin is a picaro protagonist in a picaresque series of unrelated adventures. He is the outsider who does as he pleases, thumbing his nose at the law and gleefully playing everyone for fools. The two anime also share a lackadaiscal, hippy attitude and sometimes psychedelic soundtrack. In short, Osumi gives us a show aiming for a seinen audience. The changes are stark once Takahata and Miyazaki get complete control. The seedy aspects and sexual content are cut back, the three main characters are re-jigged, noir and ribaldry give way to cheery optimism and clownish antics, the episodes gain a sense of direction (and often a sting in the tail) while losing their ambiguity, and the psychedelic edge is lost, though the overall soundtrack is still excellent without it. Lupin giggles rather than smirks and grows a heart of gold. He even spends one episode saving a damsel in distress from kidnappers in a crazy, cross-country caper in a locomotive (with nods along the way to Buster Keaton's The General). Jigen becomes a regular chatterbox, which isn't a bad thing thanks to the talents of his seiyuu Kiyoshi Kobayashi. (Speaking of seiyuu, the only weak link is Fujkil Mine's Yukiko Nikaido, who never reprised the role.) In short, Takahata and Miyazaki give us a show aiming for a family audience. The Osumi episodes are more interesting; the Takahata / Miyazaki episodes less challenging but more fun. Monkey Punch later revealed that he thought that this series was the best and most faithful adaptation of his manga and singled out the early episodes. Director Shinichirō Watanabe acknowledged Masaaki Osumi's work on the Lupin III as an influence on Cowboy Bebop. Sayo Yamamoto (The Woman Called Fujiko Mine) will revisit, in her own way, the sexual themes of the Osumi episodes. Be warned, though. The later episodes are miles away from today's anime; the Osumi episodes further away again. That said, the quality of the artwork and animation are ahead of its television anime contermporaries from Toei (Cyborg 009 or Mazinger Z) or Mushi (Wandering Sun or Marvellous Melmo).

Fujiko Mine changes. Top: beckoning Lupin (from the pilot). Middle: OP shots from the Osumi episodes - that's Led Zeppelin's Robert Plant and John Bonham. The sexual activities of the Led Zeppelin members were notorious, even in 1971. Bottom (l to r): from the pilot; the Takahata / Miyazaki episodes; and the Osumi episodes. Fujiko Mine: As can be seen from the images above, Fujiko Mine also changes across the series, and between the pilot and the series. Altering her appearance has always been part of her character (and for the others, as well), but Takahata and Miyazaki thoroughly defeminate her. They're slow and deliberate about it. When they first take over embers of the sexual frisson between her and Lupin remain, albeit implied rather than overt. By the end of the series she's simply a member of the team who happens to run off with the loot from time to time. By stages, her hair is shortened, her hemlines extended and her cleavage featured less and less. The viewer's mileage may vary here. Early on Fujiko deports herself for the delectation of Lupin and her seinen audience. If that bothers you, then the changes are for the better. I don't mind how Osumi depicts her, largely because she does precisely as she pleases, so at least she has agency. Her constant frustration of Lupin's desires fits neatly with the fantasy of woman as the unobtainable object of desire. Her name, after all, means Fuji Summit. Sadly, a fascinating exploration of human sexuality is chopped off at the knees, so to speak. I wonder how the franchise may have developed had Osumi stayed at the helm. Well, going by the poor ratings of the early episodes, not far. One series does not a franchise make. Fujiko is a seminal character within the perview of the grand survey and is a good example of how a splash of crimson may be a precursor for later female protagonists. She may have been pipped by Cleopatra - Mushi and Tezuka are first yet again - as a major adult female character in an anime with sexualised content, but she is a template for the girls with guns heroine, well before Dirty Pair. Unlike Françoise Arnoul from Cyborg 009, Fujiko's posing with a gun is an essential element of her persona and a recurring trope of the series. Her children will include the aforementioned Dirty Pair, along with Gunsmith Cats, Kite, Noir, Revy from Black Lagoon and others. There's a bit of Fujiko in each of them. Some will embrace her comic attributes; others her more serious aspects. Because the franchise is way too large to track comprehensively within my project, I plan to revisit it from time to time so that, as with Françoise Arnoul, I can see how an enduring female character is presented over an extended period. Rating: good. The original Lupin III series is a fun watch, thanks mostly to the perennially appealing bunch of characters at its core. The tonal shift brought about by the change in directors is noticeable with the sexualised noirish content of early episodes exchanged for amusing capers. The characters are strong enough and directors capable enough that the entire run is worth watching. The Osumi episodes stand out, however, as being more creative and altogether more out there. Resources: Lupin III Complete First Series, Discotek ANN The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press Recommended reading: Lupin The Third: Where To Start and What's Worth Watching, Reed Nelson, ANN

Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Nov 27, 2020 2:11 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Splash of Crimson # 5: Sayaka Yumi (& Misato)

Sayaka (left, with the titular robot) is a major character, while Misato doesn't come on the scene until episode 64. They may display contrasting personalities, but they're intended for the amusement of their male audience. Mazinger Z Synopsis: Doctor Hell wants to rule the world. To that end he maintains two armies, each with an eccentric leader, and builds giant robots with various powers. His problem is that he can't get his hands on Japanium, a metal that is nigh on indestructible. The metal is controlled by the Photon Research Laboratory, at the foot of Mount Fuji, and is used to build the mighty Mazinger Z, which, in the hands of its young pilot Koji Kabuto, stands in the way of Doctor Hell's ambitions. When the latter's ally / rival Archduke Gorgon joins the war, things become dire for everyone. - or, depending on your point of view - Sayaka Yumi is a school girl whose father, Gennosuke Yumi, runs the Photon Research Laboratory, where he builds her a giant robot, Aphrodite A, in which she fights the minions of Doctor Hell. Her equilibrium is upset when she is joined by Koji Kabuto, who is gifted an even more powerful robot - Mazinger Z. The two team up to fight the weekly robot adversary dished up by their enemies. Production details: Premiere: 13 December 1972 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #10 Chappy the Witch and Beautiful Fighting Girl #11 Belladonna of Sadness) Studio: Toei Director: Tomoharu Katsumata (Cutey Honey, Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid, UFO Robo Grendizer, Great Mazinger and multiple instalments of the Saint Seiya franchise) Source material: Majinga Zetto, written and illustrated by Go Nagai in Weekly Shonen Jump and TV Magazine from 2 October 1972 to 13 August 1974; another manga, also written by Go Nagai but illustrated by Gosaku Ota was published by Boken Oh while the anime was running. Go Nagai bequeathed us Harenchi Gakuen (ie, Shameless School), Devilman, Violence Jack, Cutie Honey, Getter Robo, Kekko Kamen, UFO Robo Grendizer, Majokko Tickle, MazinKaiser and Robot Girls Z to name just a few. Screenplay: Keisuke Fujikawa , Hirokazu Fuse, Susumu Takaku and Hiroyasu Yamaura Character design: Yukiyoshi Hane and Keisuke Morishita Mechanical design: Go Nagai, Gosaku Ota, Mitsuru Hiruta, Masaru Irago, Ken Ishikawa and Makoto Ono Music: Michiaki Watanabe (the martial mecha songs and themes) and assorted music from the Toei library by Akira Ifukube, a prolific composer who wrote numerous orchestral scores along with the soundtracks to The Burmese Harp, Atragon and many kaiju films, including the original Godzilla. Among the tunes was the same plaintive piece from Cyborg 009 that so appealed to me. I probably first heard it in a classic 1950s or 1960s Japanese movie. Perhaps I'll come across it again one day.

Clockwise from top left: Mazinger Z; Koji Kabuto at the controls of the giant robot; Boss and his two off-siders are Toei standards; Boss's junkyard giant robot; Koji's younger brother Shiro; and the professors who maintain the robots for the Photon Research Laboratory. Comments: When I was ten years of age I was beguiled by an American cartoon show called The Herculoids, a tale set on a faraway planet where a boy, his parents and five monster characters fought various wannabe rulers of the universe and other unsavoury types. What with six siblings vying for control of the one television in my house back then, I had to rely on occasional visits to friends' homes to watch it. I forgot about the show for decades until someone mentioned it on-line, bringing back fond memories from my childhood. A quick visit to YouTube quickly disillusioned me. The show is dreadful, with low production values, repetitive story lines and flat characters. But, of course, Herculoids was made for uncritical 10-year-olds, not old cynics. Because I'm watching these old Go Nagai anime for the first time I don't have the benefit or curse of nostalgia to give them resonance. I'm seeing the crap without the filter or the gloss of a child's eyes. While Mazinger Z's 92 episodes can be a chore to watch (I started in August last year), it is notable as the first anime with pilotable giant robots, starting a trope that, as we all know, is closely associated with anime. As Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy put it. "This changes the relationship between the young hero (and therefore the viewer) and the robot; instead of merely observing its actions, the viewer wears it like a suit of armour and controls it as if he and the robot were one." At times in Mazinger Z a robot's capabilities even seem a function of the state of mind of its pilot, something that will be explored in more detail in later permutations of the genre. Innovations don't happen in a vacuum. Mazinger Z premiered only two days after the sixth and final succesful Apollo landing on the moon. For those who weren't alive at the time the impact that the lunar landings, especially Neil Armstrongs first steps, had on the entire world cannot be easily overstated. Live telecasts brought to the events a novel immediacy and, along with the commentary of the astronauts in their claustrophobic spacesuits, gave he viewer the same prespective and sense of involvement that would be experienced by the young viewers of the anime.

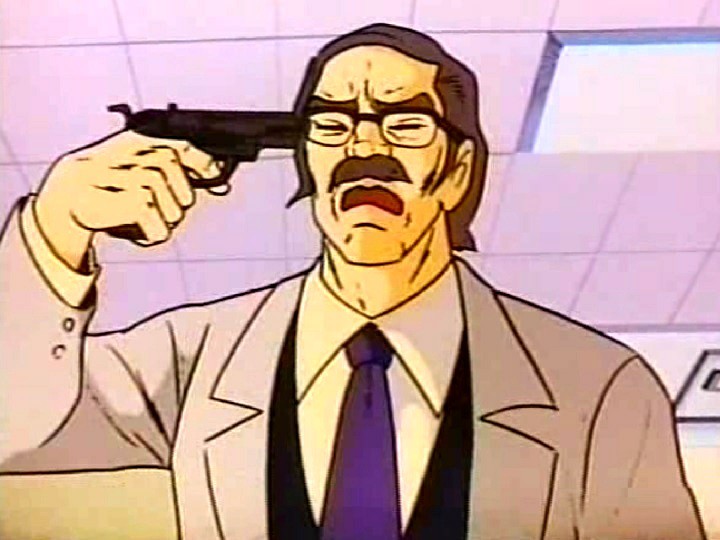

The four major villains along with samples of their mechanical beasts. Top left: Doctor Hell clenches his fists in rage as yet another mechanical beast is defeated. 2nd row, middle: Baron Ashura in a rare moment of happiness. 3rd row, middle: Archduke Gorgon - he isn't riding the tiger; he's a chimera. Bottom right: Count Brocken always enjoys his work, separated head notwithstanding. The innovation, however, comes with some of the same caveats that apply to 1973's Cutie Honey, also from Go Nagai and Toei. Firstly, the episodes are formulaic: Doctor Hell creates a new mechanical beast along with a new plan to destroy Mazinger Z and the Photon Research Laboratory, which stand between him and world domination. When all seems lost, Koji Kabuto and the giant robot save the day. Variety is mainly limited to the design and capabilities of the mechanical beasts. Count Brocken is a welcome addition to the mix in episode 40; Misato and Archduke Gorgon in episodes 64 and 68 respectively. 46 years after the original broadcast, the series comes across as tiresomely predictable. Admittedly, the battles pick up in threat and intensity in the last 15 or so episodes, but all is undone with a final episode contrivance that renders everything that had transpired thus far redundant. Secondly, the show was intended to sell merchandise to boys - hence the hero both piloting the machine and calling out the attack names. Not only that, but the moment when Mazinger Z is about to reduce the enemy to scrap metal is always flagged by the giant robot's stirring martial theme. I get the child psychology at play here. The boy viewer feels strong and re-assured, and pesters his parents to buy product for him. Anime is at its best when it pushes beyond the limitations of its merchandising. And thirdly, it hasn't aged well, lacking the otherworldy quaintness of Rainbow Sentai Robin to make up for its primitive, rough artwork and basic animation. Compounding the problem is a dearth of likeable characters. The cast isn't simply unpleasant, they're completely demented, with possible exceptions in all-purpose girl Misato, who may have a split personality in any case, and the father-figure Gennosuke Yumi, who, thanks to the behaviour of the children in his care, could be forgiven if he joined the prevailing madness. As in Cutie Honey everyone's a clown; everyone behaves shamelessly. Does that reflect Go Nagai's view of human nature? I'll be watching more of his product in due course, so I'll ponder the question further then. My favourite characters were two of the villains - Baron Ashura and Count Brocken, simply because they subverted the otherwise juvenile narrative at play. Ashura is literally half man, half woman. The right side of her / his body is female and the left male. I must admit I've pondered the form Ashura's genitals took. Who knows? Two seiyuu (male and female) speak his lines simultaneously - one of the gimmicks of the show I like. Combining masculine visciousness with feminine obsequiousness, she / he occasionally succeeds in being creepy. A signature moment occurs when, appalled at being forced by Doctor Hell to shake hands with rival Brocken, Ashura tries to wash her / his hands clean of the association. A close up of the female and male hands washing leapt right into uncanny valley territory. The sado-masochistic Ashura engenders some sympathy (not a lot, mind you) thanks to getting a raw deal from both Doctor Hell and Archduke Gorgon. For me, though, Brocken is the saving grace of the series. He was the only genuinely funny clown in the entire series. The severed head - either nestled cosily under his arm or floating nearby - flipped the narrative totally and successfully into the ridiculous, thereby redeeming it. The gimmick raised two big chuckles. On the first occasion, he forgetfully leaves his head behind when he storms out of a meeting. (When I was young my parents repeatedly told me I was so absent-minded that I would forget my head if it wasn't screwed on. Perhaps I can relate to Brocken?) In the second, in another rage, his body lashes out and king hits the closest available object - yep, his head. Despite these moments of anger, Brocken seems to actually enjoy his career as a war criminal. I could imagine him whistling as he commanded the bridge of his massive rocket-powered bomber come troop transporter. The only other happy characters in the show were the three professors working in the Photon Research Laboratory. The two most powerful villains - Gorgon and Doctor Hell - are angry, sadistic wannabe world dictators without a hint of irony or humour in their performances.

Domestic violence in the Mazinger world. These sequences are being played for laughs. That's hot soup Koji is pouring down Sayaka's cleavage. Rage is the signature emotion of the series, and not just the villains. A thread of misanthropy is woven throughout the fabric of Mazinger Z. Each of the robot pilots - Koji, Sayaka and Boss - have copious reservoirs of anger from which to draw as combatants. Indeed, the robot armour seems more impervious and the robot attacks more penetrating when the pilot has their dander up. Hot-headed, arrogant Koji exemplifies the case in point. He treats his supposed love-interest Sayaka with appalling disdain, occassionally descending into violence. She is just as apt to return the favour. I'm left wondering what domestic violence messages a ten-year-old boy - too young, perhaps, to grasp the mocking voice of the anime - would be imbibing. Koji ignores the instructions of commander, Gennosuke Yumi, leading to one disaster after another. He harasses the good-nature professors looking after the robots, lusts after Misato and treats Boss as a joke, which, I suppose he is. Oversized Boss begins as a schoolyard bully in the tradition of many a Toei magical girl show. He even has the regulation Toei short and tall accomplices. Following Koji's example he forces the professors to build him his own giant robot out of scrap iron so he has the chance to fight even more stupidly than either Koji or Sayaka. I did, however, like the low-tech equipment inside his robot, such as a steering wheel straight from a school-bus, wall-phone in lieu of a radio, a kerosene heater and a wind-up clock. Sayaka Yumi: Where Lili and Françoise are supportive of their respective heroes, Robin and Joe, and Fujiko is ambiguous as the rival and lover of Lupin III, tomboyish, hoyden Sayaka has an antagonistic relationship with Koji. If magical girl heroines aspire to be whatever they choose, Sayaka is up against a protagonist determined to ensure she is subordinate. She is simultaneously desired and loathed. Note how I'm describing her in relationship to Koji - that's how she is presented in Mazinger Z. As with Cutie Honey, female characters are portrayed in terms of their desirability and usefulness to the protagonist and, by extension, the young male viewer. Sayaka is, nonetheless, capable, which makes her alarming. The threat must be contained, violently if necessary. Despite the mistreatment (treat 'em mean, keep 'em keen) Sayaka will, at the crunch, remain loyal to Koji, sacrificing herself time and again that he may prevail over the enemy. An ongoing trope is how her robot - Aphrodite A - despite being made from the same material as Mazinger Z, is repeatedly mangled by the mechanical beasts while his robot remains undamaged. Aphrodite A is also subjected to repeated bashings, on hands and knees or prone, from the mechanical beasts. It's as if it's a displaced desire to bash the female character herself. In addition, Sayaka is prone to hysteria in a crisis situation, which limits her fighting prowess. Naturally enough, Koji and Mazinger Z will sort things out. Her fear that Koji might just prefer Misato also impairs her judgement. Sayaka may be a beautiful fighting girl but there's light years between her and Balsa (Moribito - Guardian of the Spirit).

Sayaka Yumi's robot Aphrodite A. Yes, her breasts are the nose cones of rockets. After Aphrodite A's destruction helping Mazinger Z, Sayaka gets a much improved version, Diana A. In the top right image you can see Sayaka in the pilot's cabin. Misato: As a late addition to the anime, Boss's cousin Misato doesn't get much screen time. Introduced as a contrast to Sayaka, she is domestic, pretty and feminine. She happily, even gratefully, cooks, cleans and washes the laundry of the male characters. Koji, his brother Shiro, and Boss make sure to discuss her virtues in front of Sayaka. It turns out that Misato is also a capable electronics engineer, can fly a helicopter, is handy with a gun, and the most cool-headed person in a crisis. Like Françoise she is a kind of supermum. She is desirable, useful and submissive. Rating: weak. Unpleasant characters and a juvenile, formulaic weekly narrative made this 92 episode marathon of a series a chore to watch. Mazinger Z's contribution to the development of the giant robot genre may be seminal but that can't lift the show from the mire it wallows in. Go Nagai's mockery of his characters and the current of subversiveness are as much problems as assets, contributing to the overall ugly worldview that is presented, well matched by the artwork and the character designs. Resources: ANN The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle

Gennosuke Yumi. An understandable reaction to Mazinger Z. **** I've been watching Mazinger Z slowly over several months, alongside other anime for this survery. The next two series have 125 episodes between them so it may take up to a couple of months to get though them. My plan is to include some unrelated movie reviews so the thread doesn't have long fallow periods. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

I'm most of the way through Getter Robo so, in the meantime, here's a movie review as promised. It's a blessed relief from Go Nagai.

Gauche the Cellist

Reason for watching: With director Isao Takahata passing away recently, it seemed appropriate to review what is easily my most re-watched Takahata anime. In some ways this was always likely to be a favourite: to my ear the cello is the most beautiful sounding of all the classical instruments, even when played badly by yours truly. The appeal increases when you can add, as the film's centrepiece, a performance of a much loved Beethoven Pastoral Symphony. Until recently I relied upon a bootleg version of the anime unwittingly purchased some years back from a south-east Asian website. Late last year I discovered - from an old ANN news report - that the latest Japanese official release had both English and French subtitles. This review is based on that release. (That leaves only one bootleg to be replaced - Nodame Cantabile: Paris Chapter.) Synopsis: Gauche is a cellist with a small orchestral ensemble that provides the backing music for silent movies in a small town theatre in early twentieth century Japan. The orchestra has also entered a musical competition, but, in rehearsals, the maestro berates Gauche for his poor tone, his inability to keep time and the lack of feeling in his playing. His shortcomings are not, however, for want of practice. Over four consecutive nights local animals visit a despondent Gauch in his millhouse home in amongst the farms. First to visit is a calico cat who reawakens Gauche's passion for music. Next is a cuckoo whose two note repertoire (and a famous motif of the symphony) emphasises to Gauche the importance of purity of tone. A tanuki then demonstrates how crucial a good sense of rhythm is to the expression of music. On the fourth night he is visited my a mouse and her ailing child who listen enraptured to his playing. Gauche will take the experiences with him into the competition concert. Production details: Premiere: 23 January 1982 Studio: Oh! Pro Director / screenplay: Isao Takahata Source material: Sero Hiki no Gōshu by Kenji Miyazawa (he of Night on the Galactic Railroad fame.) Music: Ludwig van Beethoven; Michio Mamiya Cello: Mitsuo Yashima Character design / animation director / key animation / layout: Shunji Saida Background art: Takamura Mukuo (Cleopatra, Heidi - Girl of the Alps, Galaxy Express 999 movie, Chie the Brat, The Order to Stop Construction, Sailor Moon)

Top: the maestro and players are transported during the symphony's storm movement. Bottom: Ludwig is not impressed with Gauche; and, of course, the protagonist is unaware that the first violin is sweet on him. Comments: Among the copious extras on the 2-dvd set is a modern recording of the Beethoven symphony accompanied by a filmed homage to Kenji Miyazawa that features artefacts - including his cello - from the museum dedicated to the writer in his home town Hanamaki, along with scenery from his native Iwate prefecture. The homage also has historical footage showing scenes of everyday Japanese life that includes a movie theatre much like the one in Gauche the Cellist. I mention these things as they draw attention to the centrality of Miyazawa's vision to the film. Takahata is faithful to the original story, adding the movie hall sequence, the symphonic concert (glossed over by Miyazawa), the coy relationship between Gauche and the first violin, and the occasional visual gag. Kenji Miyazawa was born into a wealthy pawnbroking family in 1896, but, averse to the family business and adopting Nicherin Buddhism, he declined his pawnbroking inheritance and, instead, took up teaching and writing. He died in 1933, at age 37, from a lung ailment. As a follower of Nichiren (1222 - 1282) Miyazawa would have read his works, known as "Gosho". I'm tempted to read a connection between Gosho and Goshu, but, as far as I can tell, there's no orthographic link. What I did find in my research was a blog named Daily Gosho. Today's quote neatly encapsulates a central message of the story.

Also central is the place of humans in nature and the universe. To Miyazawa all the elements of the universe live in empathy with each other. It makes sense in the Miyazawa cosmology that animals and humans might converse. The film opens with the sound of children singing to images of the night sky - the Milky Way, the Great Spiral in Andromeda and the constellation of Ursa Major - before giving way to summer images of Mount Iwate and pastoral scenes likely inspired by the Iwate prefecture. The ramparts, upon which sits the orchestra's practice hall, recall the ruins of Morioka Castle. Miyazawa's story has no specific location, however Takahata's immersion of the film in Miyazawa's native countryside is perfectly in tune with the the latter's cosmology. The symphony itself is a paeon to life in the countryside, embellishing and emphasising the themes of the story. Beethoven once confided that the third movement included a portrayal of a village band struggling to play while half asleep, a notion echoed by Gauche's small orchestra. Gauche must tap into this harmony. Enlightenment may be found in self-awareness, in knowledge of one's place in the universe.

The cat steals the show. Well... along with the music. Takahata brings his own genius for direction to the story. He shares with his contemporary, and stylistically very different, Osamu Dezaki an ability to get the emotional trajectory of a scene absolutely right. Where Miyazawa has Gauche bursting into tears at the criticism of the maestro, Takahata can engage our sympathy without the histrionics. But, then, he has more tools at his disposal - the glorious music along with the art of his animators. Famously, he couldn't draw, but his eye is nigh on impeccable in Gauche the Cellist. Much of the credit must go to his background artists, led by Takamura Mukuo, who also contributed to the exquisite backgrounds of Heidi - Girl of the Alps. Interior scenes, dominated by browns and greys are simple, allowing the animators to give full expression to the characters and their movements, which, while not always complex, are highly effective. Shunji Saida even took cello lessons to get the movements right. Exterior shots are frequently static, or with some panning to follow the movements of the characters, who, as often than not, are small figures in a wide landscape. They share that landscape with its other elements, being no more or less signifcant than the trees or the clouds or the streams or the bridges. The watercolour style, with greens, browns, blues and golds dominating, is both artificial and timeless. Clearly, care was taken to draft the backgrounds to be as pleasing to the eye as possible. Without multiplaning and with little action, the exterior scenes rely on the artwork for their appeal, and usually succeed. Gauche the cellist is a handsome film. Gauche himself epitomises the enlightenment theme of the film, demonstrated not only by his improvement on the cello, but also in his changing relationship with the animals. The cat infuriates him, whereas the cuckoo merely annoys him. Gauche is then won over by the tanuki and, finally, treats the mice graciously. The animals not only instruct him in his art but also how to live authentically. That said, I've always found Gauche somewhat unappealing. He has a sourness and a self-centredness that, to my mind, doesn't quite fit the tone of the film. Yes, he changes, but his generosity towards the mice never convinces. Nor am I persuaded that communing with nature - without and within - would improve Gauche's attack on the second string of his cello.

The animals are variable. The mother mouse is an earnest, formal, cloying supplicant. The cuckoo is annoying, as intended, but, unlike the cat, can't transcend the role given him. I did like how his rigid thinking - you might say he is a two-note character - prevents him from learning from his window misjudgements. The tanuki is sweet. His wide-eyed bewilderment at Gauche's provocations charmed me, while his guileless, yet pointed, questions are disarming. When Gauche blames the cello for his poor attack on the second string, the tanuki looks directly at him and asks simply what was wrong with the instrument. Gauche, of course, has no answer. The star of the show, though, is the cat. The moment he walks in the door, both Gauche and the film are transformed. In an art form that is feline-centric with many a memorable cat, he remains my favourite to this day. He his cheerful, sly, clever, smug, well-meaning and tortured mercilessly by Gauche. His demented dance as Gauche plays Tiger Hunt in India is easily the visual and dramatic highlight of the film, but, placed so early on, leads to something of a dramatic letdown for the rest of it. The reprise of the piece at the end simply can't match its entertainment value. The cat may be a trickster but he is the most sympathetic character in the film. One element that can match the cat is the music. Beethoven's Sixth Symphony - premiered in 1808 with his more famous Fifth Symphony - is gorgeously apt for Miyazawa's vision. Takahata inserts the movements out of order, beginning the film with the fourth movement depicting a brief but violent storm. Again he is front-ending the most dramatic elements of the film as if he wasn't confident he could capture his audience's attention. From there on the symphony weaves its way triumphantly through the film, putting to shame Disney's feeble effort with the same work in Fantasia, though, in his favour, Takahata has more time at his disposal. Gauche does conclude with the final movement of the symphony, which repeats, in sonata rondo form, one of the most ecstatic melodies ever created. You could say the film ends on a high note. Well, F-major chords actually. Rating: Very good and trending. Over time my regard for the film has grown. In a reflection of Miyazawa's artistic vision the various elements of Gauche the Cellist are in a discourse with each other: Takahata's choice of location; Miyazawa's choice of the music; the parallel between music and nature; the role of the animals and the landscape in Gauche's transformation. If Beethoven or Buddhist philosophy or rustic, talking animals aren't your thing then look elsewhere, but you'll be missing a distinctive, finely honed film. Resources Gauche the Cellist, Japanese Ghibli Collection - it came with a really neat Ghibli Collection desk calender I now proudly display at work. ANN The font of all knowledge Gauche the Cellist, Kenji Miyazawa, trans Paul Quirk, Little J Books via Kindle Daily Gosho, 25 May 2018 The World of Kenji Miyazawa, Who is Miyazawa Kenji? Symphony No.6 Op.68, "Pastoral", Philharmonia Orchestra, conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy, Decca, accompanying booklet.

**** Given recent events here's an index of my Takahata reviews. I think I've done more from him than any other anime director. It wasn't planned - things just turned out that way. Horus - Prince of the Sun (1968) Lupin the 3rd (1971) - scroll to the top of the page! Panda! Go Panda! & Panda! Go Panda!: Rainy Day Circus (1972 & 1973) Heidi - Girl of the Alps (1974) Anne of Green Gables (1979) Chie the Brat (1981) Gauche the Cellist (1982) fits in right here Only Yesterday (1991) The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013) Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Jun 16, 2018 8:19 pm; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Splash of Crimson #6: Michiru Saotome

What! I'm not the most interesting thing about the series? You can't be serious. Getter Robo Synopsis (compare with Mazinger Z above): At the time of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event some dinosaurs survived in protected pockets in the earth's mantle. Emperor Gore, the leader of a now sophisticated dinosaur empire wants to reclaim the surface world by ridding it of its human inhabitants. To this end he creates an army and builds giant mechasaurs with various powers. Standing in his way is the mighty Getter Robo, a giant transforming robot built by the Saotome Research Institute, piloted by three young men: Ryo Nagara, Hayato Jin and Musashi Tomoe. When the evil demon Yura joins the war, things become dire for everyone. - or, depending on your point of view - Michiru Saotome is a school girl and fighter pilot whose professor father runs the Saotome Research Institute dedicated to the harnessing of Getter energy from Cosmic Rays. He builds a giant combining robot, powered by Getter energy and piloted by three boys from her school: Ryo Nagara, Hayato Jin and Musashi Tomoe. She joins the team as their flying scout in their battles against the weekly mechasaur dished up by Emperor Gore. Production details: Premiere: 04 April 1974 Studio: Toei Director: Tomoharu Katsumata (see Mazinger Z) Source material: the manga Getta Robo, written by Go Nagai and illustrated by Ken Ishikawa published in Weekly Shōnen Sunday from January 1974 to May 1975 - for the most part concurrently with the series. Script: Shunichi Yukimuro Screenplay: Shozo Uehara Music: Shunsuke Kikuchi Character Design: Kazuo Komatsubara Art design: Tadanao Tsuji

Top l-r: Ryo Nagare, Hayato Jin (who owes more than a little to Ashita no Joe's Tohru Rikiishi) and Musashi Tomoe Bottom l-r: the Getter Robo transformations they respectively command - Gurren Lagann, anyone? Comments: Toei, Katsumata and Nagai return with a new franchise introducing new wrinkles to the formula they had established with Mazinger Z. In between the two series they also produced the groundbreaking (and likewise formulaic) Cutie Honey. Go Nagai's association with the two genres - giant robot and magical girl - resulted in cross pollinations that have had a lasting impact on each. Cutie Honey borrowed from Mazinger Z the trope of the protagonist calling out the attack name, while gifting to Getter Robo the tranformation sequence. So, once again Go Nagai and team give as a mind-numbingly repetitive show replete with innovations. This is, famously, the first giant robot show featuring rocket planes that combine to make something altogether different. Depending on the order that Ryo (red - Getter 1), Hayate (white - Getter 2) and Musashi (yellow - Getter 3) join their aircraft, the resulting robot has functions that reflect the individual personality of the controlling pilot. Some sleight of hand is involved - the skin of the aircraft must be stretched and distorted to create the new machine; new appendages must grow from nothing. We haven't yet reached the precision and intricacy of the later Transformers. Mind you, the intended audience wouldn't have minded, as this passage I found quoted in Anime: A History explains:

The increase from one pilot to three co-pilots gives the creators more narrative scope than was available to them with Mazinger Z. (Serious Ryo is nominally the protagonist, but, as the series progresses, easily excitable, goofy Musashi takes more and more of the limelight.) Not only must the monster of the week be defeated, not only must the pilots learn how to use their robot effectively, they must also learn to co-operate, something that doesn't come naturally thanks to their headstrong personalities. Teamwork is essential to deploy Getter Robo rapidly and to ensure that the best transformation is chosen. In early episodes the three compete to have their own version of Getter Robo take on the new mechasaur, usually with disastrous results. The outcome for the viewer, compared with Mazinger Z, is both a more interesting dynamic between the team members and less reliance on sexual tension with the token female character to provide conflict. This, in turn allows Go Nagai and company to tone down the trademark "shameless" sexual mayhem, though hints remain, such as Getter Robo 2's tiny penis, Michiru's nipple buttons and Professor Saotome's collection of nude paintings on the research laboratory walls. Unhappily the stupid, slapstick humour remains - the comic relief trio of a mad inventor with his neon-toothed robot and his pox-headed apprentice is a blight on the series. I suppose the humour is intended for 7 year old brains, but then why the penis, the buttons or the paintings? I wonder if they're for the creators' own amusement.

To left: Emperor Gore is just a conquest motivated, authoritarian villain, without any interesting character traits. Top right: a sort of elvin / gecko cross, the dinosaur mooks are unintentionally cute. Below: assorted mechasaurs - compare with Mazinger Z or the Panther Claws of Cutie Honey. A major retrograde step from Mazinger Z is in the entertainment value of the villains. Other than the surprisingly appealing dinosaur troopers, whose deaths sometimes engender sympathy, the villains are dull. The aeons long entrapment of the dinosaur empire within the earth's magma - how that is possible is never explained - and their understandable desire to live under the sun is the basis of a contest with humans that could leave the viewer conflicted. Instead, the producers emphasise the brutal and supposedly frightening nature of the leaders and the mechasaurs. Funnily enough, as often as not, they come across as ridiculous, which, given this is a Go Nagai franchise, leaves me wondering if the effect is his intention. Just the same, none of the four dinosaur leaders can match the genuine creepiness of Baron Ashura or the amusing Count Brocken from the earlier show. Their counterparts - General Bat and mechasaur builder Chief Galeli - display some rivalry but altogether lack eccentricity. The motivations of the four, along with their captains, are limited to exterminating humans, ingratiating themselves to their seniors or brutalising their subordinates. On the positive side, there's the aforementioned combining robot and somewhat more sophisticated narrative around the development of the pilots. To this can be added improved artwork and animation, while retaining the trademark Go Nagai garish palette. One upgrade I enjoyed was the explosive demise of all the mechasaurs. Where in Mazinger Z the beast robots sometimes exploded unimpressively but, just as often melted or vaporised, the mechasaurs detonated with a characteristic double banger - there's an initial smoky explosion, then a bright light appears amid the smoke and a second, titanic, erruption follows. By the latter parts of the series the pyrotechnics have escalated to mushroom cloud dimensions. Oddly, Tokyo Tower is destroyed no less than four different times. One of the fun things about this survey is discovering unexpected influences on later, and these days more well known, anime. Gurren Lagann derives much inspiration from Getter Robo, though in affectionate homage rather than lazy mimicry. I also see some Neon Genesis Evangelion. Another step forward is the ending. Yes, once again the creators pull a rabbit out of the hat, but at least the rodent this time is a new villain, not an unflagged saviour. The biggest improvement, however, is that, with its mostly episodic nature featuring a monster of the week, Getter Robo comes in at only 51 episodes compared with Mazinger Z's 92. As with the even shorter Cutie Honey these shows are tiresomely formulaic. The shorter the better.

Getter Robo explosions. Tokyo Tower gets a regular hammering. The Eiffel Tower, too. Come on, you know it won't stop Tokyo Tower being a strange attractor for magical girls. Michiru Saotome: In Beautiful Fighting Girl Tamaki Saito credits Go Nagai as helping "invent the beautiful fighting girl as an object of sexuality... Nagai somehow managed to discover (or invent?) an original otaku-esque sexuality". The earliest example he gives is the half-naked machine gun toting Jubei from the 1968 manga Shameless School, while full expression is found in Cutey Honey and Kekko Kamen. Saito also draws a contrast between them and the fighting girls of his early mentor Shotaro Ishinimori, who gave us the seminal Françoise Arnoul from Cyborg 009. As Saito points out, and should be apparent from my reviews, "In Nagai there is a disposition toward excess that makes even Ishinimora look like an ascetic." At its best that excess is amusing; too often, to my eye, it is ridiculous. I had been saving those quotes for this review, but it turns out that Getter Robo doesn't illustrate Saito's point as well as either Cutie Honey or Mazinger Z. Michiru Saotome, like other elements in the series, is toned down compared with either Honey Kisaragi or Sayaka Yumi. More Françoise Arnoul than Kekko Kamen, she is highly competent as a pilot and isn't ever caught in shame inducing pickles. For sure, her form-hugging uniform is sexy (but so are Ryo's and Hayato's) and she is the object of desire for at least three of the male characters, but she doesn't flaunt her sexuality the way Honey does. Nor does it become the site of ridicule or violence as suffered by Sayaka. That makes her, like the show in general, more appealing, but less peculiar and thereby less interesting.

Michiru Saotome. That's her father in the top image. The buttons are distracting. Rating: not very good. As with the other Go Nagai anime, groundbreaking thematic elements are brought undone by tiresomely formulaic episode structures. Paradoxically the show is more fun to dissect than it is to watch.The innovations are there to see and the Go Nagai eccentricities abound, if toned down, but once the viewer has wintessed the novelties in the first few episodes there isn't a lot to encourage them to hang around. Resources: ANN The font of all knowledge Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 4:29 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Utsugi

Posts: 10 |

|

||

Oh man, this anime. It's one of my favorites amongst the other WMTs. The comedy is just really spot on. The way the two sisters play off each other was just wonderful. Dunno about the French dub but I watched it in Japanese and the voice acting was fantastic. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

^

The anime gets the blend of comedy and drama just right. I'd love to own a subtitled version of this series. Did you know that, at the time the anime was broadcast, Japan was Australia's biggest source of tourism? The Japanese-friendly-sounding Yepoon on the Queensland tropical coast became a favourite destination, though not without some conflict from reactionary Australians. (Yohachiro Iwasaki still owns the resort.) |

|||

|

|||

|

Utsugi

Posts: 10 |

|

||

Yeah, Japanese fansites talk about how there was an Australia boom at that time. Flonne, the WMT before it, was about a Swiss family going to Australia only to get stranded in an island. And they also have an Aboriginal character in it. The kid accused Flonne and her family as being murderers before being befriended. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

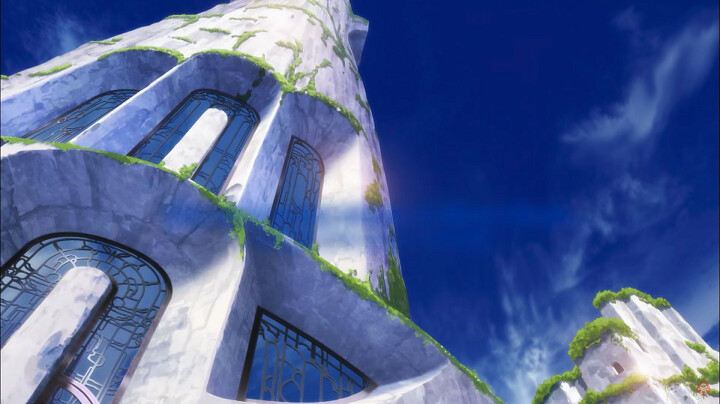

Maquia - When the Promised Flower Blooms

Only anime could get away with a mother who likes like a fourteen year old. Reason for watching: I try to see as many anime cinema screeings as I can. Four o'clock on a Thursday afternoon certainly was potentially awkward, but it so happens I'm on holidays. Please treat this as an impression, rather than a review. Synopsis: Maquia is a young member of the reclusive Iorph clan who live in teenage form for centuries. They specialise in weaving cloth they call hibiol that is prized by otherwise hostile normal humans. Into the fabric they weave their memories and their emotions, all of which can be read by other Iorph. Thus the treasured hibiol contain the history of the clan. When the community is attacked by men riding dragons (known as renato) in order to abduct the clan's elder, Leilia, for marriage to the son of the local potentate, Maquia is one of the few who escape alive. In her flight she discovers a human baby - still in the embrace of his murdered mother - and takes him into her care. Thereafter Maquia leads a peripatetic life thanks to her ageless appearance putting her at risk of detection. Forever fifteen in appearance, but growing in experience and wisdom, her bond with the yound Ariel brings her great joy, but also sadness, as she observes and participates in the entire life that she had, in a sense, granted to him. Production details: Premiere: 24 February 2018 - its Australian premiere was earlier in the week. Studio: PA Works Director / script / storyboards: Mari Okada (her directorial debut; she is notable as a script writer having wrote or contributed to the following anime that I've seen: Aria the Natural, Simoun, Toradora!, CANAAN, Gosick, Hanasaku Iroha, anohana - the Flower that We Saw that Day, Lupin III: The Woman Called Fujiko Mine and Blast of Tempest). Source material: orginal work - this is Mari Okada's baby. Music: Kenji Kawai Character design: Akihiko Yoshida and Yuriko Ishii Art director: Kazuki Higashiji Chief animation director: Yuriko Ishii Art design and conceptual design: Tomoaki Okada (are they related?) Comments: At first blush this appears an unexceptional anime: The character designs don't break the anime mould; the backgrounds, while PA Works gorgeous, are in line with current trends; the fantasy setting is nothing out of the ordinary and the ubiquitous Kenji Kawai provides a competent soundtrack. Thematically, however, Maquia is highly unusual in that it explores the meaning of being a mother, with all the joys, tribulations and sorrow that brings. Not only that, but it asks the even more fundamental question of what makes a woman a mother. That might seem a silly question - surely giving birth makes a woman a mother you might respond - but the scenario we are immersed into permits the anime to dig deeper. Other anime I can think of that approach this emphasis on motherhood are Marvellous Melmo, which is more focussed on the mechanics of procreation, Bunny Drop, where the mother-figure is actually male, and Wolf Children, but while that film begins as the mother's story, it subtly transforms into being the chldren's story, as its title portends. Okada's title likewise tells the viewer whose is the most important narrative thread. It is, in this instance, entirely the mother's. That's not to say other things aren't going on - this is an epic film after all. There's the destruction of an ancient culture, the decline of a royal dynasty, dragons facing extinction through an inexplicable malady, an invasion, a forced marriage, romantic rivalry and a conventional courtship. The thing is, any one of these threads could have been the central story, but they all end up not only peripheral but executed somewhat perfunctorily - pointedly so it seems to me - though they're not without interest in their own right.

Maquia and her adoptive son Arial. So, how does Mari Okada set up her motherhood scenario? In short, by making her protagonist an unlikely and unintended mother. From an early age the members of the Iorph clan are taught not to have close relationships with normal humans. Any love of that sort can only end sadly. The flim doesn't articulate exactly why no humans live amongst the Iorph but I assume it's partly because the Iorph want to be left alone and partly because humans don't like them. Any Iorph living among humans risks mob harassment. Even if those issues were to be overcome, the difference in life expectancy guarantees a lifetime of grieving. To this scenario can be added Maquia's discovery of the baby, the only survivor of a nomadic troupe slaughtered by bandits. Maquia empathises with the child - after all she has just witnessed the massacre of her own clan - and feels that fate has placed a duty upon her, that the child is her hibiol. Ill-equipped for the responsibility and all too aware of the differences between herself and the child, whom she names Ariel, she constantly questions what it is she must be and do to become the child's mother. The issue is exacerbated by their apparent ages. A mother of 14 or 15 is strange enough to the people she meets, but as Ariel grows while she doesn't, the relationship becomes more peculiar to the humans and more challenging to Maquia. Conversely, Ariel faces his own dilemmas: how does he define himself in relation to a mother who is so different; how does he deal with her agelessness; how does he explain her to his human friends and associates. What transcends it all is the profound love they come to have for each other. They will each learn the gift the other is and, in time, willingly accept the attendant responsibility. Maquia's path is reflected, or contrasted, with other women - Mido, the single mother who is the first human to take her in as boarder; Dita who gives birth as battle rages nearby; or Leilia's bitter history with her daughter. Mari Okada is also making a social, historical and, dare I say, feminist point. Here we have something of a rarity in anime - a female anime director. Not many others come to mind. I can only think of two more off the top of my head: Sayo Yamamoto (Michiko and Hatchin, Lupin III: the Woman Called Fujiko Mine, Yuri!!! On Ice) and Chiaki Kon (When They Cry - Higurashi, Junjo Romantica, Nodame Cantabile: Paris Chapter and Finale, Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon Crystal: Season III to name some). In her directorial debut she tells a woman's story from the woman's point of view, then surrounds it with a bunch of more conventional narratives frequently found in anime directed by men and assigns them a secondary level of significance. In particular, the contrast between Dita giving birth at the moment her husband is almost killed in a futile battle as he slips on the blood of one of his vanquished foes brings Okada's intentions front and centre: that the woman's story is more fundamentally important. This emphasis on Maquia's point fo view is also reflected in how the flow of time is presented. The rapid changes to the characters around her can be jarring. From one scene to the next a character can age years. A war begins and ends seemingly in a flash. For Maquia change is relentless, rapid and laced with partings. This gives the film quite an emotional clout, so expect the tears to flow. In typical Okada fashion she can be heavy-handed, though I didn't feel as manipulated as I was with anohana. She also has a tendency to verbosity, though not nearly as bad as the middle episodes of Blast of Tempest.

PA Works backgrounds are exceptionally good. I've long been a fan of the background artwork in PA Works projects. Shows like CANAAN and Angel Beats! set new standards for their time. Maquia is a treat in this regard. Not only are the settings detailed and colourful, there is a magical interplay of light and dark. The sheer, transparent hibiol are beautifully done. The comparatively simple two dimensional character designs seemed at first incongruous against the intricate computer generated backgrounds, something that bothers me in cinema screenings more than it does at home. I think the spectacle of well composed backgrounds are emphasised in a cinema thereby bringing into stark relief the artificiality of the character designs. Speaking of which, I wasn't overly enamoured of Maquia's design - her face had enough residual puppy fat to be slightly unnerving given her growing maturity and insightfulness. It isn't a big complaint and, that said, she's a great character. Full marks to Mari Okada there. I might also add before concluding that the film shares a couple of tropes with Simoun, an anime for which Okada scripted nine episodes: women who retain their adolescence indefinitely; and a society waging a losing war. Simoun's background artwork divided people, so what a difference twelve years make. Rating: a harsh very good. I fear that I overrate films when I see them at a cinema. In that environmnt the spectacle can mask shortcomings. When I watch it again at home I'll decide if deserves a higher score. First time director Mari Okada provides a compelling treatment of an uncommon subject for anime - motherhood - in a moving and graceful film that is sometimes overwrought, sometimes verbose, and yet at other times brusque in its treatment of secondary themes. The central relationship between the protagonist and her adoptive son is beautifully realised. Resources: Madman - the images are from their website ANN Jonathon Clements review at All the Anime Kim Morrissy review here at ANN The font of all knowledge MAL Last edited by Errinundra on Tue Jun 12, 2018 7:23 pm; edited 2 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Redbeard 101

Oscar the Grouch

Forums Superstar Posts: 16963 |

|

||

|

Color me jealous you got to see it in theaters. Reviews I have seen have fluctuated mostly between the overall movie being either just good, or amazing. Some have been more critical on the actual plot and messages than others. The one pretty universal opinion though is that artistically this is a wonder of a movie. That being said be able to see it in an actual theater definitely would enhance that experience.

So yea, jealous indeed. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Even if the plot and the message were dismal it's worth seeing at a cinema for the visuals. As my report above argues, the structure of the plot is determined by the message. If the viewer isn't receptive to the message then the plot becomes problematic. A lot of anime fans would be indifferent to hostile to any perceived prioritising of a woman's story.

As an anime fan I feel quite privileged to be living in Melbourne. Four of the five Australian anime distributors have their head offices here: Madman, Hanabee, Siren Visual and the latest player, Umbrella Entertainment. (I think Madman and Hanabee warehouse their stock in Sydney, however, which is where Sony Universal can be found.) With a population of just over 4.9 million, Melbourne is large enough to have a thriving fan base. What's more it is a highly Asianised city, especially in the Central Business District. Places like Melbourne Central and the Queen Victoria Centre are popular locations for Melbourne's Asian community. And where do I get to see anime films these days? Hoyts in Melbourne Central, of course. When I saw Fate/stay night: Heaven's Feel I. presage flower as far I could see I was the only person of Caucasion appearance in an otherwise full house. Vive la différence! |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|