Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Blood-

Bargain Hunter Bargain HunterPosts: 24161 |

|

|||

She is definitely not the main character nor could she be considered an equal in an ensemble cast. "The Lazy General" Ikta is definitely the main character. Yatori, however, is most definitely kick-ass. |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girls index

**** Proto-Beautiful Fighting Girl #1 Chameko's Day Synopsis: Chameko-chan wakes up, washes her face and teeth, dresses, eats a hearty breakfast, walks to school, answers the teacher's questions correctly and goes to the movies. Production details Year: 1931 Studio: Kyoryoku Eiga Seisaku-sha (Co-operative Film Productions) Director: Kiyoji Nishikura Music: Koka Sassa

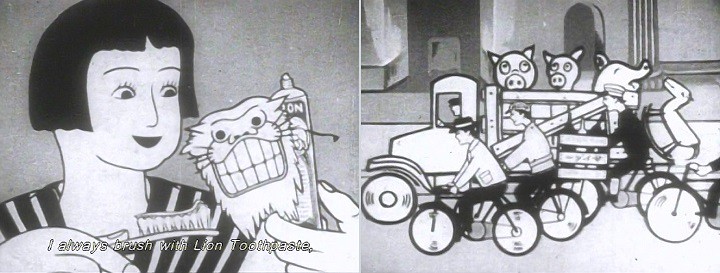

Product placement and city traffic in 1931; the rocking horse on the back of the bicycle is just one of the oddities. Comments: Wouldn't you know it? A slice of life anime featuring a school girl in a sailor suit from 85 years ago. I guess some things never change. I have no idea if this was a popular or influential film in its time. Getting information about it is nigh on impossible, beyond the notes in the booklet that comes with the Zakka Films release The Roots of Japanese Anime until the End of World WWII. Neither The Anime Encyclopaedia nor Anime: A History mention it, although the studio is mentioned in connection with 1932's The Lucky Taxi Pilot (Ōatari Sora no Entaku), where Nishikura is credited with either the photography (ANN) or artwork (The Anime Encyclopaedia). The six minute film is a phonograph talkie, meaning that the film is technically silent, however a synchronised phonograph was played as the film was projected. With few spoken parts, most of the soundtrack is sung by child star Hideki Hirai and two singers from the Asakusa Opera, Ruby Takai as Chameko's mother and Teiichi Futamura as her teacher. The Asakusa Opera, featuring opera, operetta, US musicals, and sketch comedy such as variety shows and vaudeville, flourished in the early twentieth century. To some it signified the start of Americanisation of Japanese culture, so how appropriate it is that two of its singers would be involved in a cartoon, so associated with America. The film's composer, Koka Sassa, was also a key figure with the Asakusa Opera.

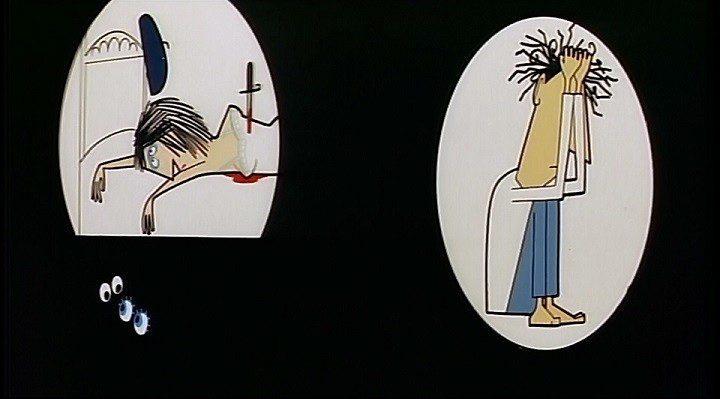

Left: Chameko's brush with death. Right: a brief mix of live-action and animation. There are some odd parallels with today's anime, not so much in the production techniques or visual style, but, rather, in its media mix and marketing strategies. For starters, the film is based upon Hideki Hirai's own hit song from 1929. More eyebrow raising is its brazen advertisement for Lion Toothpaste (see image above), which is still sold in Japan to this day. How about that - product placements in anime in 1931. It wasn't the first anime to be used to sell other products, either. Way back in 1918 Ōishi Ikuo’s The Hare and the Tortoise (Usagi to Kame) lured viewers into an auditorium where Morinaga chocolates were sold. In 1923 Lion Toothpaste went so far as to commission the instructional film Oral Hygiene (Kō kūEisei). Other oddities make their way into the film. On the way to school Chameko gets collected by a car, thrown over its roof and lands dazed in a side street. I know I'm watching a cartoon - and, for sure, the incident is presented humorously, but it comes across as surreal. Cut from the film, and missing from the DVD, was an perjorative reference to a crippled person as an izari. One of the movies Chameko sees features Sazen Tange, a fictional samurai character popular in live-action movies at the time. Although not depicted as such here, he is notable for his scarred face and missing eye, acquired following a betrayal. (I've just realised that Danpei Tange from Ashita no Joe was likely inspired by him.) Here he announces, "What? A sneak attack is cowardly. Meet your match," and promptly beheads his three prisoners. 1931 was the year the Sino-Japanese war began, a war that didn't end until the defeat of Japan in World War 2. The conflict between the Asian neighbours was triggered by the infamous Mukden Incident of 18 September 1931, when Japanese soldiers staged a fake sneak attack on their own South Manchuria Railway, blaming Chinese dissidents and using it as a pretext for invasion. If the anime is alluding to those events, and I admit I find it altogether too tempting at times to relate Japanese creative endeavours to historical events, then it is a chilling foretaste of the atrocities to come. In any case, if the film was released prior to the Mukden incident, and I cannot find a date more precise than 1931, then the parallel cannot be valid, of course. Chameko's movie viewing also includes live-action newsreel footage of Japan's first female Olympic medallist (silver in the 800 metres event, 1928), Kinue Hitomi, who - the weird correlations continue - died on 2 August 1931.

Left: mushrooms in sailor suits. Right: unflagged violence concludes the film. While there is no evidence of a lineage between Chameko's Day and later Beautiful Fighting Girls I'm still bemused by some of the thematic connections and contrasts. Visually, Chameko is chunky when compared with today's whippet thin heroines. The similarity lies with the shared conjuction of the hallowed school girl with violence, of eros with thanatos. She's not yet the dispenser of death, though she does have a sort of insouciance when it comes to her own injury and to the content of the Sazen Tange movie, declaring, "Let's go again next Sunday!" over the headless corpses. Visually and musically it's crap, to be honest. In fairness, any cartoon from that era looks bad. In preparation for this review I watched Disney's 1931 black and white cartoon Mickey's Orphans and his 1932 colour cartoon Flowers and Trees, films of similar length to Chameko's Day and which were both nominated for Best Animated Short Film in the 1932 Academy Awards (Flowers and Trees won). They may look ordinary to my 2017 eyes but they are quite a few steps ahead of their Japanese counterpart. The artwork, animation, humour and palette are, without doubt, superior. Still, they don't have a cute school girl in a sailor suit as their protagonist. Rating: as an artefact, important; as a viewing experience, bad. At only six and bit minutes long you're not going to regret watching it, but the black and white artwork is primitive, the narrative dull - other than the bizarre moments - and the music somewhat worse than unexceptional. Resources: The Roots of Japanese Anime until the End of WWII, Zakka Films ANN The Font of all Knowledge Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle The Anime Encyclopaedia 3rd Revised Edition: A Century of Japanese Animation, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle https://www.rem.routledge.com/articles/asakusa-opera Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Apr 28, 2018 11:47 am; edited 5 times in total |

||||

|

||||

nobahn

Subscriber SubscriberPosts: 5150 |

|

|||

|

Fascinating.

(Just for laughs, here is another video clip.) |

||||

|

||||

Blood-

Bargain Hunter Bargain HunterPosts: 24161 |

|

|||

|

Interesting start. However, I'm a little confused on your methodology. Why is Chameko's Day considered a proto-beautiful fighting girl? Unless I missed something, it doesn't sound like she did much fighting.

|

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

As I said in the introduction to the project,

The key factor is whether she's the protagonist, but even then, I'll be briefly looking at a couple of secondary or support characters in Captain Konga from Kimba the White Lion and Françoise Arnoul from Cyborg 009, from the early days of TV anime, as they are models for later female leads. |

||||

|

||||

|

Animegomaniac

Posts: 4158 |

|

|||

Ever see 1929's Skeleton Dance, the first of Disney's Silly Symphonies? To call it revolutionary is standard, to say it was animated almost entirely just by one guy, Ub Iwerks, is just an unimportant fact. To say it's still amazing to this day that can not be stressed enough... I wasn't surprised to find it on Youtube but the almost 10 million views did surprise me. I also found Chameko on youtube... posted two days ago... one view... now that's a comparison but I guess my viewing doubled it. Selected articulation, not enough drawings per second and often the wrong ones at that, no character animation, lingering background shots but there were some good morphing, it was very Fleisher influenced, right? They were just getting their Betty Boop series in full swing at the time but the guys who invented rotoscoping a decade earlier know how many drawings per second you need for smooth motion. I thought the real oddity was the image of Charlie Chaplin on the side of a truck that caught the daikon in the road; That... was a thing that happened. Don't ever change Japan, and you haven't. You could have just said "To me, any cartoon from back then looks bad" and stressed as a personal opinion but in fairness, Flowers and Trees won because of its technicolor process which Disney helped innovate if not outright create. If you think about it in animation terms, going from black and white to total color... not the red/green two tone process... is probably even more important than sound. Movies were doing sound for years at this point but color? |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

^

Thanks for the suggestion. Skeleton Dance puts Chameko's Day in the shade. I also think it is more entertaining than either Mickey's Orphans and Flowers and Trees. Beyond the impact of its colour, the narrative and subject matter of the latter are dull.

It's a review, so it is, by it's nature, my opinion. Later that paragraph I added such a disclaimer: "They may look ordinary to my 2017 eyes..." I'm egotistical in that I love the sight of my own words, but not so much that I think I'm the last word on any matter - see my responses to the Haruhi posts. |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Proto-Beautiful Fighting Girl #2

Kumo to Tulip (ie, Spider and Tulip) Synopsis: A spider attempts to lure a ladybird beetle into his web, but, realising her peril, she escapes into the petals of a tulip. The spider seals the flower with his thread, but his intentions are thwarted when a storm intervenes. Production details: Released: 15 April 1943 Studio: Shouchiku Douga Kenkyuusho Director: Kenzo Masaoka Story: Michiko Yokoyama Music: Ryutaro Hirota Comments: Finding allegorical messages in Kumo to Tulip is overwhelmingly tempting thanks to the times in which it was made and to the blackface minstrel appearance of the villainous spider, so examining the catrastrophic strategic situation confronting Japan at the time of the film's premiere is worthwhile. In June 1942 the American Navy decisively defeated the Japanese in the Battle of Midway (despite what Kancolle might have viewers believe). Although the Japanese still maintained a slender materiel advantage in the Pacific for a brief period thereafter, allied victories in New Guinea (Kokoda and Buna-Gona) by January 1943 and, more importantly, Guadalcanal by February 1943, meant that the strategic initiative had transferred to the Americans and their allies, whose greater capacity in producing weapons and in training pilots, along with the tactical advantage provided by radar, was to ensure that the initiative wouldn't be wrested back. Kumo to Tulip was made in the period between the effective loss of the war at Guadalcanal and the commencement of the bombing of the home islands of Japan, which was, by then, inevitable. Estimates of fatalities from the subsequent destruction of Japanese cities range from 240,000 to 900,000.

As I pointed out in my review of Chameko's Day, Japan had been on a war footing since 1931, following the Mukden Incident and the invasion of China. The military Government enacted a new Film Law in 1939 that required that all people involved in film production be licenced (and thereby monitored), and that forbad damaging the national interest or questioning the Emperor or the constitution. Studios, including Shochiku, actively supported the government. Shochiku's president, Shiro Kido, helped set up the Dai Nippon Eiga Kyokai (Greater Japan Film Association) for that purpose. He and the company co-founder Takejiro Otani were arrested after the surrender by the occupation authorities and charged with war crimes. That all said, one important thing that stands out with Kumo to Tulip is how it avoids the military preoccupations of its anime contemporaries. There are no heroic Peach Boys, talking animals, or everyman soldiers bringing freedom to the Asia-Pacific from the yolk of colonialism. Instead we get a menacing blackface spider and a sweet-natured and, dare I say, kawaii ladybird beetle, whose spots on her back could, at a stretch, be conflated with the Japanese flag. Does the storm that overwhelms the spider represent the coming battles that just might, miraculously, bring about an allied defeat? Or does it suggest that the natural order must inevitably favour the Japanese? I don't know. I think taking the allegory that far is unnecessary; one need not load the film with any interpretive baggage beyond the Americans being the bad guys. However you look at it though, the threat of annihilation is effectively conveyed. On a technical level the film is a step forward from Chameko's Day from thirteen years earlier. Having pioneered cel animation in Japan, Director Kenzo Masaoka uses it here in an interesting and highly effective way. While the characters and the web are hand drawn, the backgrounds were filmed using real plants (flowers, branches, leaves, briars) with soft focus and cleverly placed lighting creating a dream-like atmosphere of fragile beauty. The characters, particularly the ladybird, move in the three dimensional space of the plants, providing a visual sophistication way ahead of Chameko's Day. Be warned, though: the image quality requires some indulgence from the viewer. Whether it's the low resolution of the You Tube version, the ravages of time on the film stock or limitations faced by Masaoka, or a combination of all three, I can't say for sure. I wonder how it would have looked in a hall in 1943. Post war, Masaoka's ideas on animation were taken up by the animators who would later work for Toei and thereby spread to other companies.

Ryutaro Hirota's melodies are attractive, despite the ladybird's scraping pseudo-juvenile voice. The spider makes up for her with his dulcet tones, whether sung or spoken. Close your eyes and you can hear the seduction in his voice. Unfortunately, the blackface, the pork pie hat and the large hands with their pale palms don't sit well with our modern sensibilities. Nevertheless, his roguish behaviour is appealing enough that I found myself rooting for him as he struggled to save himself in the storm. For her part, the ladybird combines innocence, wide-eyed wonder, sprightly behaviour and a vulnerability that suggest moe decades before it become the anime norm. (Did you know, by the way, that almost all ladybird beetles are, themselves, voracious predators?) Shochiku has, quite possibly, been making anime longer than any other company in Japan. It began as a Kabuki production company in 1895 (and still is) and added film production to its repertoire in 1920. While Shochiku's most famous live-action film is probably Yasujiro Ozu's Tokyo Story from 1953, they were in the vanguard of the Japanese New Wave of the 1960s. Their oldest anime that I've found so far is Masaoka's The World of Power and Women. Made in 1932 and premiered the following year, it was the first anime talkie. These days their anime involvement seems to be mostly in distribution, though they still can be found credited with production. In 2017 they are putting their name to Kabukibu!, which is appropriate given their origins. Rating: as an artefact, priceless; as a viewing experience, decent. Inventive filming and animation techniques, a dreamy atmosphere, and interesting historical connections are undermined by poor production quality, a screechy female lead and racist overtones. At only sixteen minutes, you won't waste your time. Resources: Anime News Network - the ANN index links to the wrong anime The Font of all Knowledge Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle The Anime Encyclopaedia 3rd Revised Edition: A Century of Japanese Animation, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Shochiku Animation History of Shochiku Frames of Anime: Culture and Image Building, Tze-Yue G Hu, Hong Kong University Press Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Jan 13, 2017 9:30 pm; edited 1 time in total |

||||

|

||||

Blood-

Bargain Hunter Bargain HunterPosts: 24161 |

|

|||

|

The use of blackface to (possibly) represent an American is an odd choice. I didn't think that black Americans were all that much in Japanese consciousness during that time period. Coincidentally I happen to be reading John Toland's The Rising Sun right now which is all about Japan gettting its ass kicked in WW2. Not that I really needed it, but the book is once again a vivid demonstration of the evil that arises when civilian authority loses control of the military.

|

||||

|

||||

|

yuna49

Posts: 3804 |

|

|||

Off-topic, but I found this comment ironic considering the furore which China's recent decision to revise its history textbooks has generated: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/11/world/asia/china-japan-textbooks-war.html |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

I guess it's a matter of perception. To me, Manchuria is part of China. To invade it is to invade China, in the same way that to invade Tasmania would be to invade Australia (how that might be done, though, requires some imagination). The Chinese see it that way but, it would seem that some Japanese prefer a different interpretation - I assume along the lines that Manchukuo wasn't historically or legitimately part of China. I think that view is self-indulging.

|

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

This week I'm looking at two mysterious female characters, though mysterious for entirely different reasons. What's more I won't be reviewing either movie, again for different reasons.

Proto-Beautiful Fighting Girl #3 & Beautiful Fighting Girl #1 Princess of Baghdad Synopsis: I don't know. I'm unable to find a copy for viewing, nor can I find a plot summary. The best I've been able to manage is four images from the film. Production details: Released: 1948 Studio: Sanko Eiga-sha Director: Iwao Ashida Story: Iwao Ashida (as Hiromasa Ashida) and Toshiro Wakabayashi Music: Ryoichi Hattori Animation: Risaburo Fukuda

Comments: In 2004 a resident of Fukuoka donated an almost complete version of the Princess of Baghdad to the city library. Working with Japan's National Film Centre, who had an incomplete version of the film, they were able to restore it, enabling the first viewing for many years of what the library claimed was the first post-war animated film. The Anime Encyclopaedia simply says that "it was lost until the 21st century, and hence not part of anime chronologies." In the available images the titular character looks both coy - note how in each image above she uses one hand to partially cover herself - and beguiling. Her smile and eyes suggest a self-confident character. What is her role? Is she the protagonist? Or the object of desire for a male protagonist? Do things end badly for her? Or well? I like to imagine her as a schemer who makes fools of the pompous courtiers surrounding her. That's the tantalising thing about some of these arcane titles - I'm left floundering with unsupported supposition. Searching for the Sanko Film Company was only marginally more fruitful. IMDb credits them with eight films made between 1936 and 1951, all shorts except for The Princess of Baghdad, which clocks in at 48 minutes. I had more success with Iwao Ashida, who directed ten films according to IMDb. His real name was Hiroki Suzuki, but, displaying considerable profligacy, he also used Tomohiro Suzuki and Hiromasa Ashida. Going independent in 1936 his company also used various names, including Suzuki Cartoon, Sankichi Cartoons (could that be Sanko Film Company?) and Ashida Cartoons. During the war he worked as part of the "Shadow Staff" making instructional animated films for the military. These films covered topics from piloting aircraft to bombing techniques. After the war and following The Princess of Baghdad he gained an international reputation for his short films and contract work with Amercan advertising agencies. For a decade or so - until the advent of Toei and TV animation - his company, Ashida Cartoon Film Production Works, was seen as the leader in the industry, although most lucrative work was in advertising. Thereafter things declined rapidly. According to The Anime Encyclopaedia, "His studio, once the centre of the Japanese animation business, became a mat shop." Should I ever have the opportunity to watch this film, I'll revisit it in this thread. **** Now for the first fully-fledged Beautiful Fighting Girl. Because I've reviewed this already, I'll briefly look at the character Bai Niang and her importance in the evolution of the beautiful fighting girl. Bai Niang from The Tale of the White Serpent Synopsis: Bai Niang is a female serpent spirit who comes to love a young male human who treated her kindly. Defeated in battle and banished from the temporal world by an exorcist monk, she appeals to God to allow her to return for the sake of her love. (A full review from only three months ago can be read here.) Production details: Released: 22 October 1958 Studio: Toei Doga Director: Taiji Yabushita Screenplay: Shin Uehara Music: Chuji Kinoshita & Hajime Kaburaki Animation (among others): Gisaburō Sugii & Rintaro, both of whom would have careers as directors

Comments: In the best tradition of beautiful fighting girls, Bai Niang is a subversive character. For starters, she's demonic, even if she never does anything harmful and only relutctantly fights the monk. You could say she is the original magical girl, transforming from human, to sorceress, to serpent. That said, she is meant to be both the object of desire, although her character design might not succeed for you when measured against our modern notions of two dimensional beauty, and the sinister object of fear. She is woman as other. She is mysterious, ineffable. Now, you might expect her role as other would site the male, Xu Xian, as the point of view character, but one of the oddities of the film is that he, for the most part, plays the hapless lover. Exiled, he has little to no agency. The Tale of the White Serpent never seems quite sure who the protagonist ought to be. Bai Niang, Xu Xian and the two pandas who support Xu take turns as lead characters. It is up to the pandas and Bai Niang's fishy maidservant to rescue him, while she fights for her right to love him. The name of the original American release - Panda and the Magic Serpent - is apposite in that it neatly states who are the important agents in the narrative. While Xu Xian is dismissable, and the pandas and the fish-girl amusing, the problematic, and most interesting, character is the serpent, Bai Niang. In Beautiful Fighting Girl Saito Tamaki places Tale of the White Serpent at the fountainhead of the phenomenon he examines, not only because of its historical place, but also for its impact on the career and thematic obsessions of Hiyao Miyazaki. He cites an article by Miyazaki, "Making Animated Films," published in Shuppatsuten where the director states that his career as an animator began when he saw the film in high school. The experience was a formative one, in part because he fell for the heroine. He would later disparage the film as shoddy and state that his feelings were merely a "substitute for a girlfriend", but paradoxically, he would go on to create his own films with female characters - Clarice from The Castle of Cagliostro, Nausicaa from Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, Fio And Gina from Porco Rosso, San and Lady Eboshi from Princess Mononoke - who are representations in anime of that same sexuality. The beautiful fighting girl becomes, for us, as it did for him, a mild form of trauma. She is desirable, but, as a two dimensional fictional construct, she is unattainable. Loss, for the viewer, is intrinsic to her nature. The drawback with this approach is that it presumes a male heterosexual viewer, without accounting for other sets of eyes that may gaze upon these heroines. But, I am a male viewer who has fallen for them and who has been mildly traumatised by them. Other responses are equally legitimate, but what intrigues me is how an entire industry grew around male viewers' fascination with female protagonists. This project aims to explore that unusual relationship. Resources: ANN: Princess of Baghdad; The Tale of the White Serpent IMDb Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle The Anime Encyclopaedia 3rd Revised Edition: A Century of Japanese Animation, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press Japan Times Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:50 pm; edited 1 time in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

This week's post is the first of two looking at the early works of Osamu Tezuka and his studio, Mushi Pro. It's a bit of a stretch to call the "friendly girl with a teddy bear" a proto-beautiful fighting girl, but she is as much the protagonist as any other character in this ensemble piece. She could also be seen as a link between Chameko and later magical girls. Mostly, though, it's an excuse to review my favourite Tezuka anime (up there with the much later Jumping).

Proto-Beautiful Fighting Girl #4: the Early Contributions of Osamu Tezuka Part 1

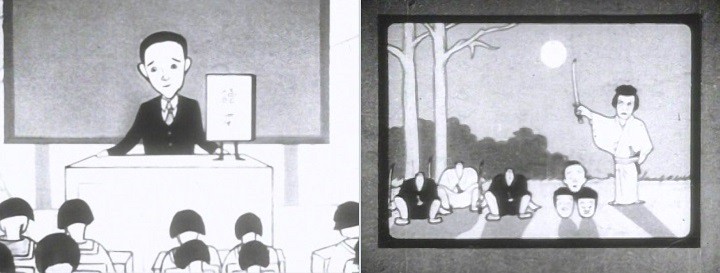

The poster encrusted laneway. The old street lamp and the tree on the corner bookend the film. Tales of the Street Corner Synopsis: Prior to, during and in the immediate aftermath of a war, a laneway is the setting for a series of dramas involving a girl and her misplaced teddy bear, an inquisitive mouse, a moth with attitude, a spluttering street lamp, a tree that is shedding leaves and seeds, and an array of posters that come to life. A ruthless dictator transforms the laneway, but also brings destruction upon it. Life is unquenchable, however, so, in the rubble left by war, there is a new beginning. Production details: Released: 5 November 1962 Studio: Mushi Pro Original Creator and Executive Producer: Osamu Tezuka Director: Eichi Yamamato (poached from Otogi Pro) Music: Tatsuo Takai Art and/or animation: (among others) Gizaburo Sugii (poached from Toei), Shigeyuki Hayashi aka Rintaro (likewise) - they would go on to be directors for Mushi and other studios Camera: Kazuyuki Hirokawa - would also go on to be a director with other studios

Osamu Tezuka: first with green hair. That's the "friendly girl with the teddy bear". Osamu Tezuka and Mushi Pro: Starting with a 4-panel gag manga in the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper in 1946 (while still only 17 years of age), Tezuka revolutionised and then dominated manga in Japan with his cinematic layouts and his complex story lines. His 1947 manga The New Treasure Island sold 400,000 copies, which considered in the context of the time - American occupation after the destruction of every large city in the country - was a remarkable feat. This was followed by such famous titles as Metropolis (1949), Jungle Emperor (aka Kimba the White Lion, 1950-54), Astro Boy (1952-68), Princess Knight (1953-56) and his life's work, Phoenix (1954-89, incomplete). The period also included his vesion of the Monkey legend, also known as Journey to the West - Son-Goku the Monkey (1952-59). Toei had decided to use the story as the basis for their third feature film, which would be released in America as Alakazam the Great (reviewed here), so hired him as a consultant, which amounted to him storyboarding the film. Indications are that Tezuka took on the role to further his own ambition to start up an animation studio. Upon completion of the project he, well, decimated Toei - taking 10% of their animation staff with him to work at his newly created Mushi Productions. He also nicked staff from the second largest animation company, Otogi Productions, and the advertising industry. (At the time most filmed advertising in Japan for TV and cinema was animated, not live action.) Wanting his cake and eat it as well, he set out to make anime as art and, separately, anime for profit. Tales of the Street Corner would fall into the former category, while the TV version of Astro Boy would pave the way for a profitable future. Things didn't turn our so rosily. Comments: Oddly enough, Tales of the Street Corner didn't get a general release at the time, so wasn't widely seen until released on DVD in the first decade of this century. (In Australia it was part of Madman's Tezuka: the Experimental Films set.) While I think it's an outstanding anime for its time, it's hard to acknowledge its influence on the industry, other than the obvious experimentation with limited animation that Tezuka would push even further with Astro Boy. I'll come back to the limited animation in a moment, but, having recently re-watched the first four Toei films, the thing that leaps out from the screen is how revolutionary, how different, how alive this film is, compared with those forebears. Tezuka is rejecting the leaden motifs of those films by embracing a modern, expressionistic, European visual sensibility. Ironically, given Tezuka's admiration of Disney, those same qualities, along with its manga sense of framing and movement, and the lack of dialogue, make it an anti-Disney film as well. In this instance Tezuka's expressionist approach is more influenced by eastern European and Russian animation than American. The setting appears to be French, while the music could be straight from a Jaques Tati film. (Mon Oncle was released in 1958 and shares with Tales its droll, gently mocking humour, its warmth and a similar "gay but somewhat repetitive musical score"). What goes around, comes around. Bruno Bozzetto's 1976 masterpiece, Allegro non Troppo, is heavily influenced by this side of Tezuka, while later anime has nods to the Italian film. (Wouldn't you know it, both Mon Oncle and Allegro were released on DVD in Oz by Madman.)

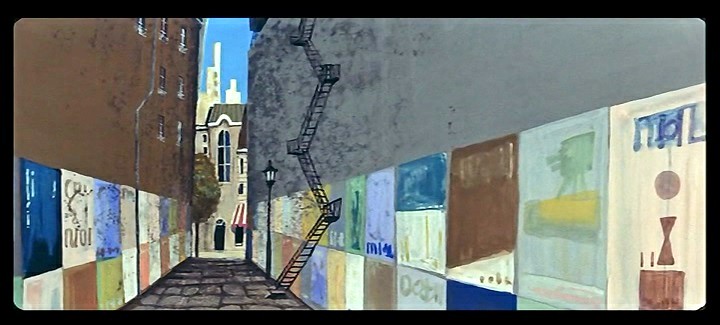

Osamu Tezuka: first with twin tails. Them aside, these are some of the recurring characters in the film. I've done the punk moth a disservice. He isn't really ogling the girls. Tezuka is in the process of giving anime its visual identity, what makes it so distinctive from American and European animation, or even the Toei films with their heavy-handed approach to creating a particular style. The little girl aside, Tales isn't an obvious visual forerunner to Astro Boy or Kimba the White Lion. What he is bringing to the short film is his manga sensibility and his depiction of movement. In his commentary track to the film, Australian film-maker, graphic designer, composer, sound designer and educator (quite the polymath!) Philip Brophy points out that animators who don't come from a comic or manga background are impelled to make things move. That's what animation is all about, surely? Tezuka and other manga artists are coming from a format where, movement is suggested by gesture, framing and familiar semiotic conventions such as speed lines. There isn't the same impulse to create movement in the animation. This creates economy and, more importantly, a peculiar Japanese approach to the art form. In Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito argues that this codification gives manga and anime their unique combination of high context and atemporality (ie, narrative time is independent of reading/viewing time) that promote rapid processing without much movement. He slates the revolution home to Osamu Tezuka. I would argue that Tales of the Street Corner is its first manifestation in anime. (Saito, develops his ideas further to argue how this high context atemporality is one of the factors that leads directly to anime's phallic girl, but more on that another time.) Tezuka goes even further, by bringing manga framing into the film via one of its principal gimmicks - the posters on the laneway walls. They are manga pages, in all their split panel variety, brought to life in a film. Two long segments have the camera lingering on the posters as they dance to the jaunty soundtrack. Dozens upon dozens of images sweep by, all with their characteristic goofy, at times somewhat black, humour. They are for me, highlights of the film: all with a gag of some sort. The panels... er... posters interact with each other - two are lovers, while a third is a jealous observer. The dictator steps from the cobblestones of the laneway onto the wall to become his own glaring poster that spreads like a virus, as if part of a metaphorical anime invasion of manga.

Samples of the many poster panels in the film. Did you say, don't mention the war? There's no avoiding it. Tezuka lived through the war and witnessed the firebombing of Osaka. Tales of the Street Corner is specifically about such a conflict. The style of the posters and the architecture place the early scenes as pre-World War 2. The destruction of the city, including the laneway, as well the imagery of the weaponry displayed on the transformed posters reinforce the analogy. For a time in the twenties European expressionism was avant garde in Japan, until clamped down upon when the government become more militaristic, nationalistic and isolationist. The film unabashedly lampoons the dictator/general. His worldview destroys his world. In the end, life is renewed in the rubble, giving the film a fatalistic, cyclical sense. The very name of the film and its confined setting also suggest that only the abstract notion of place is permanent, that human endeavour is transient. As with the manga sensibilities, this is a very Japanese way of seeing things. It's also a very humanist one. There's a quote on the inside of the DVD case from Tezuka: What I try to [say] through my works is simple… just a simple message that follows: "Love all the creatures! Love everything that has life!" I have been trying to express this message in every one of my works. Over fifty years later, this film still manages to convey his optimism. Rating: excellent. Tales of the Street Corner encompasses an entire world of possibilities, including strife, tragedy and renewal. Despite the short running time, the limited setting and the basic artwork and animation, there is more joy and creativity here than you may find in many a multi-episode anime series. I think it's the first great anime ever made.

Afterword: My admiration of the film isn't universally shared. Here's a contrary view from Jonathon Clements from Anime: A History:

Last word: Philip Brophy from the commentary track to the Madman release:

Resources: ANN Tezuka in English Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle Osamu Tezuka: the Experimental Films, commentary by Philip Brophy, Madman Entertainment DVD The Font of all Knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia 3rd Revised Edition: A Century of Japanese Animation, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press

Tezuka outside the Mushi Pro studio. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 3:21 am; edited 2 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Proto-Beautiful Fighting Girl #5: the Early Contributions of Osamu Tezuka Part 2

Osamu Tezuka: first anime girl with a gun. More on her later. This post is dedicated to violence, cruelty and the excesses of the imagination. Only the third anime covered in this post actually involves a beautiful fighting girl, and then only as a secondary character. The other two examine themes that are central to the trope or, rather, the expectations men have about about women, which is, after all, a feature of said trope. In this early post in the project I think it's interesting to explore the milieu from which anime's fighting girl springs. **** Male Synopsis: Two cats carousing beneath a bed find themselves distracted by the fidgeting behaviour of the male human owner of the bed. Their complaints and suggestions that humans should approach sex the way cats do are interrupted when police arrive to arrest the man. Production details: Released: 5 November 1962 (at the same screening as Tales of the Street Corner) Studio: Mushi Pro Producer: Osamu Tezuka Original plan and rendition: Eiichi Yamamato Storyline and key animation: Shuji Konno Eiichi Yamamato: there isn't much information to be found about this pioneering anime director, seemingly always in the shadow of Osamu Tezuka. Born in Kyoto just before the outbreak of the Pacific war, he spent the war with his mother in Shodoshima while his father was called up for military service. Immediately upon graduation from high school he joined Otogi Productions under Ryuichi Yokahama, before becoming, for all intents and purposes, the house director at Mushi Pro. With Mushi Pro sliding into bankruptcy, Yamamoto left to supervise the making of Space Battleship Yamato.

Comments: at just over three minutes, Male doesn't have much time to make its arguments. I include it here because it illustrates one aspect of men's treatment of women: violence. The viewer can readily imagine why the male character has killed his lover. What is interesting here is that the narrative is provided via animation. Now, at the time of the making of this film, anime hadn't yet developed its own visual language for the fetishisation of its female subjects - that will come shortly, but it is tempting to see the woman as both the victim of the male character's desire to control her, as well as being an artefact entirely controlled by the film's creators. You think this interpretation is too speculative? Whose iconic hat is hanging from the bed? Tezuka's, of course. I doubt he's confessing to an actual murder, but I believe he is telling us that him putting a woman in a film is, in an important sense, an act of murder. Her voice can only ever be the voice he gives her. My postmodern inclinations tell me that I, as viewer, can creatively re-interpret the story anyway I see fit, but then I become guilty of the same crime as Tezuka. My Beautiful Fighting Girls project will have this thought as an undercurrent. As a two dimensional image the beautiful fighting girl is artificial; as a voice for women she is fake. I don't think that's necessarily a bad thing. So long as my imagination is aware of the distinction between the woman on screen and the real women in my life then I can allow anime to take me to some very interesting places. Technically the film continues the very minimal animation of Tales of a Street Corner. Black space dominates with spotlights revealing fragments of the murder scene, providing a sense of movement where there is none. The minimalist soundtrack is restricted to the nervous tapping of the murderer's fingers, the feline commentary and the wail of the police siren. The whole thing comes across as gimmicky, just another throw away clever idea of Tezuka's. Rating: not really good. **** Mermaid Synopsis: A young man finds a small fish in a pool by the seashore. In his imagination the fish becomes a mermaid, whom he takes home and keeps in a tank of water. His parents see only a fish; the authorities see only a fish, so the young man must undergo treatment to cure him of his imagination. Production details: Released: 1 September 1964 Studio: Mushi Pro Original story, rendition, animation: Osamu Tezuka Music: Isao Tomito, which is a bit rich given that the sole piece of music used is Claude Debussy's Prelude to an Afternoon with a Faun. I suppose it could be argued he adapted it.

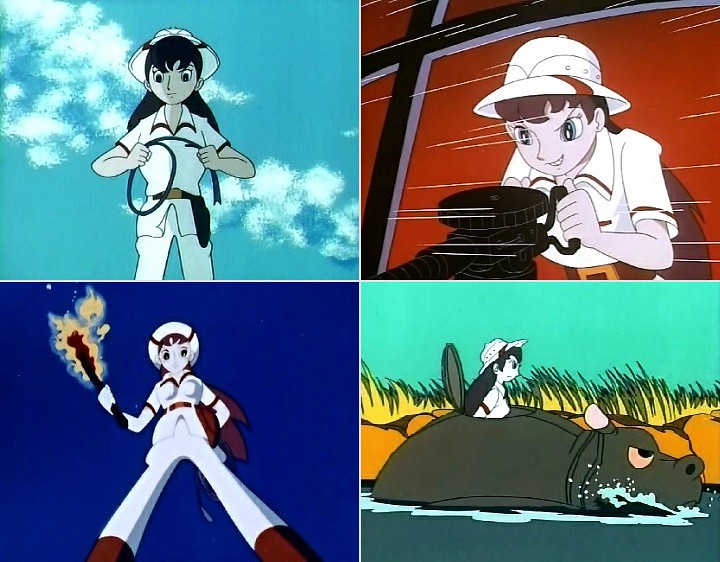

Comments: On one level, and I think it's the more persuasive interpretation, Mermaid is a satire on the Japanese education system of the time, which was seen by some as stifling children's creativity. Addtionally, the narrative happily reflects one of the themes of this project: the place of the female character in the male imagination. The boy in the film is analogous to the modern otaku - to us, the viewers of beautiful fighting girls. I'm not saying that this is intentional on Tezuka's part: it just coincidentally parallels the journey I'm taking in the thread. You could say the film is a sign of things to come. Mermaid is more sympathetic than Male towards its male character. After all, the villain here is social conformity. As in Male, one could view the character as representing Tezuka himself. However you look at it, the boy's imagining of the fish as a mermaid is presented sentimentally, so that the viewer is tempted to wish the mermaid becomes reality for him, as, in a way, she does. The sentimentality is tempered somewhat by the Tezuka's satire and by his characteristic ironic humour. I could turn it around, rather, and say that the pomposity of the social order of the film is contrasted and made stark by the affecting, imagined relationship. A notable feature of the film is it use of Prelude to an Afternoon with a Faun, from which the film gets its emotional cues. The choice works well, but, for me, also turned out to be informative in an unexpected way. I mentioned in my previous post that Bruno Bozetto's marvellous Allegro non Troppo owes much to Osamu Tezuka. Bozetto's film has its own animated tale set to Debussy's popular piece so it's easy to see the two sequences as companion pieces. Bozetto replaces the boy with an old man, in the form of an imp, surrounded by beautiful, naked women. Whereas the boy assimilates the mermaid into his imagination, the old faun fails to impress the nymphs, despite his increasingly desperate efforts. The cross-fertilisation between Tezuka, Bozetto and later anime directors is a thread that winds through the animation medium. Bozetto's justly famous evolution sequence, set to Ravel's Bolero, not only references Walt Disney's Fantasia, but also Tezuka's The Genesis. Allegro non Troppo would go on to inform Rintaro's own Labyrinth and Mamoru Hosoda's Digimon Adventure: Born of Koromon. Technically, the artwork is as basic as Male's, while the animation is barely more complex. In both short films, Tezuka attempts to integrate his themes with his limited animation style, or, rather, use the themes to compensate for the technical limitations. Both films come across as scrappy but mildly interesting, lacking the scope and the stream of visual creativity of Tales of the Street Corner. Rating: not really good. **** Mary / Captain Tonga from Kimba the White Lion Production details: Released: 6 October 1965 (Mary first appears in episode 3 on 20 October 1965) Source Material: Jungle Emperor, in Manga Shonen, by Osamu Tezuka, published from November 1950 to April 1954 Studio: Mushi Pro Chief Director: Shigeyuki Hayashi (aka Rintaro) Series Director: Eiichi Yamamoto American Director: Fred Ladd Music: Isao Tomita A full review can be found here. Background: After the success of Astro Boy, Tezuka pitched Kimba the White Lion, to NBC Enterprises. They backed the project but NBC's Fred Ladd decreed that it must be a series, not a serial. Tezuka managed, all the same, to include a number of story arcs, spread out in single episodes across the 52 episode run. One of the odd things about the anime is that the narrative, and I'm only familiar with the American version, isn't always coherent. Mary's story, told in six widely spaced episodes, is full of plot holes, improbabilities and contradictions.

Mary, pre-memory loss, showing us how to swing a cat, namely Kimba, and attempting to blow her toes off. Mary and Roger neither recognise nor remember Kimba when they visit Africa. Odd. Arc synopsis: Mary is a modern woman who travels the world with her fiancé, Roger Ranger and his Uncle Pompous. When, on a hunting trip to Africa, their aeroplane crashes, Mary and Roger find themselves lost in Kimba's jungle. The two are subsequently separated by a rock fall, with Roger - thinking her dead - staying to help the jungle animals create a new society, while Mary wanders off suffering from amnesia. Found and adopted by a wealthy businessman she reappears as Captain Tonga, running a large, private game reserve - the Hunting Grounds - where hunters come to slaughter wild animals. Kimba quickly becomes her number one sought after prize. The question is, will Roger trigger her memories before she exterminates Kimba and his jungle friends? Comments: I've gotta say Mary as Captain Tonga is quite a remarkable villain. There is very little moderation about her. When she does bad things she does them in epic proportions. Her war on Kimba will come to include whole battalions of tanks and missiles. Goodness knows how she financed it all. Even as the supposedly sweet and loving Mary she is irritable, self-centred and jealous. In a prelude to the African part of the story she constantly and bad-humouredly competes with Kimba for Roger's attention. The image of her tossing Kimba by his tail in the Louvre, as seen above, is an example of her poor humour. Likewise, her irritation at being marooned in the jungle must be borne stoically by Roger. It also leads to the accident that brings out the monster in her.

Whips, guns, oh my! Nice to see her smile for a change. Osamu Tezuka: first with amphibious hippo tanks. Tonga's villainy is epic in two ways. The first is her cruelty. She not only stocks her vast Hunting Grounds with copious numbers of captured animals, she starves and tortures them to make them wilder - all for the pleasure of the game hunters. Remember, this is a children's show! The second is her Cecil B DeMille level of monstrosity. In one sequence, where she has been commmissioned to cull elephant numbers in an overpopulated national park, she sets out to kill every last one. She achieves this by stampeding them, using the firepower of her private army, into a canyon cul-de-sac where she slaughters them all (except two, as it turns out). I'm talking hundreds of elephants here. Two of her invasions of Kimba's realm would have succeeded but for divine intervention. Yet, for all that, she's my favourite character in the series after Kimba. While her madness has a sort of grandeur to it, she is constantly undermined by show's humour. Her minions are a bunch of clowns. She has a habit of violently extending her arm to show the way or express her enthusiasm, an act that invariably king hits one of her henchmen. When she pounds tables to make her points, her underlings scramble to catch the objects that bounce off, lest they smash. Her violent schemes inevitably go awry, leaving her flat on her face and, if she were a normal person, thoroughly humiliated. Undeterred she carries on blithely. I find that quality appealing. Despite her early place in the canon, Tonga is a quintessential girl with a gun. Her pose at the top of the post has all the elements I've come to expect from the trope: left foot forward, right foot back, gun and steely gaze directed at her victim, left hand facing backwards. You'll see it with Françoise Arnoul (Cyborg 009) in my next instalment in the project, while Mireille Bouquet (Noir) will make the pose her own. For sure, the trope existed before anime. Gunslinger Annie Oakley was the star of a travelling show at the turn of the twentieth century, while such characters are a standard of film noir. Cathy Gale and Emma Peel from the British TV series The Avengers popularised the type in the early to mid sixties, so may have had a direct influence on the anime, though obviously not the manga. Mary / Captain Tonga brings a distinctive film noir twist to anime - the monstrous woman as subject of redemption. We know that she's really, in her heart, one of the good guys. We also know from the get go that she only needs to regain her memories - and there's another girls with guns trope - to be forgiven for all her evils. Sure enough, she bumps her head, recognises Roger and the two travel home, along with Uncle Pompous, to live happily ever after. The last we see of the three is their journey by raft down river into the sunset. But, who is the real woman? Superficial Mary? Or underlying Tonga? Whoever it may be, the monster is more entertaining.

Tonga takes her big game hunting very seriously. Resources: ANN: Male; Mermaid: Kimba the White Lion Tezuka in English Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle Nishikata Film Review The Anime Encyclopaedia 3rd Revised Edition: A Century of Japanese Animation, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle The Font of all Knowledge I'm sure someone will now point out a gun wielding girl in Astro Boy or Gigantor. Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:58 pm; edited 2 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Proto-Beautiful Fighting Girl #6: Françoise Arnoul (aka Cyborg 003)

As much as I love this image from the OP used in both movies, it's a tease. Dig those eyelashes. Cyborg 009 Cyborg 009: Monster Wars Synopsis: The two films follow pretty much the same trajectory. The nine cyborgs, created from ruined bodies by the nefarious Black Ghost organisation, rebel and dedicate themselves to fighting evil and corruption from around the world. In each film the heroes must locate and defeat the Black Ghost himself at his latest secret hideaway. On the way they confront legions of monsters and machines. On arrival at Black Ghost's lair treachery and skulduggery await them. Production Details: Released: 21 July 1966 and 19 March 1967 (Monster Wars) Source material: Saibōgu Zero-Zero-Nain, by Shotaro Ishinomori, in various magazines, July 1964 - 1981 Studio: Toei Doga Director: Yugo Serikawa (Anju to Zushio Maru, reviewed here) Key Animation: Mao Lamdo

Cybernetics aside, Joe Shimimura is a prototype for many anime heroes. Shotaro Ishinomori: A protege of Osamu Tezuka and one time resident of the famous Tokiwa-sō apartment building, he would eventually surpass his mentor's output to become the most prolific manga artist of all time. He not only created the Cyborg 009 franchise, but also Kamen Rider and was involved in the creation of the Super Sentai concept. Along with Tezuka and others he established the "look" of anime and introduced superhero teams. He died in 1998, just three days after his sixtieth birthday. Overwork, perhaps? By his death he had published 120,000 pages of manga, while over 2000 episodes of anime and tokesatsu have been adapted from his works. Comments: What a difference five years makes. In that time Toei Animation and director Yugo Serikawa went from fusty period dramas to fully embracing a popular manga franchise, with a manga visual aesthetic. Had I watched these films when they were released, that is, when I was eight or nine years of age, I would have loved them to pieces, what with their monsters (I would have flipped over the dinosaurs), the superhero team with their individual super powers, the mysteries of the hidden lairs, and the frequent cartoonish battles. Toei also brings its widescreen movie format to the franchise, along with a vivid palette, where bright colours shine against a pastel or subdued background. (Did you know that "vivid" comes from the Latin "vividus" meaning "animated"? Cool, hey?)

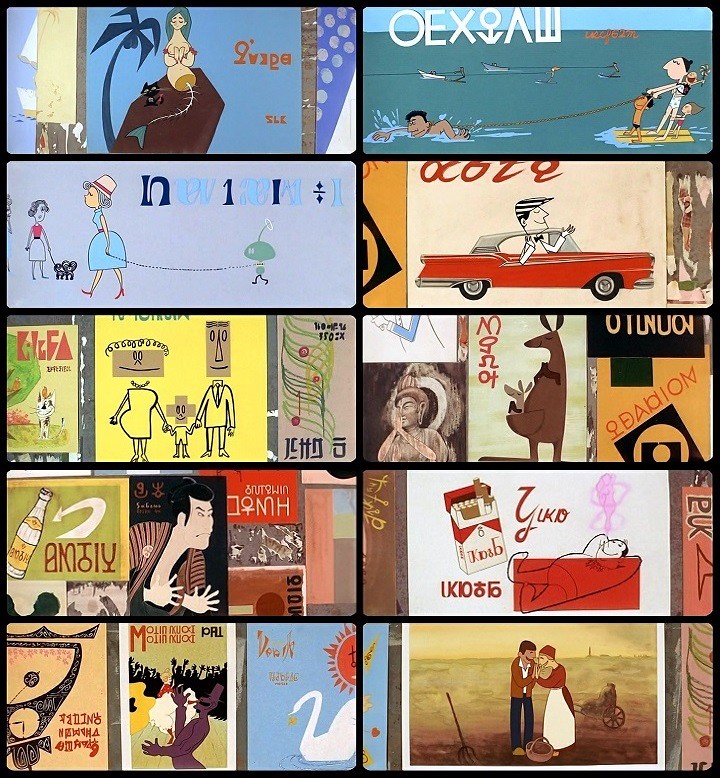

The cyborg team (left to right, top to bottom): 001 - Ivan Whiskey (Russian) - enhanced mental capacity, including psychic powers; 002 - Jet Link (American) - flies at supersonic speeds; 003 - Françoise Arnoul (French) - enhanced vision and hearing; 004 - Albert Heinrich (German) - a walking, talking arsenal of machine guns and rockets (where does he store all the ammo?); 005 - Geronimo Junior (native American) - immense strength and armoured skin; 006 - Chang Changku (Chinese) - oral flame throwing; 007 - Sir Great Britain (British) - shape changing - Shotaro Ishinomori didn't like the childish form used for comic relief and to appeal to children; 008 - Pyunma (African) - combat and underwater specialist; and 009 - Joe Shimamura (Japanese/American) - many super-powered attributes that make him the most capable of the cyborgs. Although I'm reviewing the films because of Françoise Arnoul's role in the development of the beautiful fighting girl in anime, she is actually overshadowed by other innovative developments on screen. While Cyborg 009 was pipped by 8 Man as the first cyborg anime, it develops Ishinomori's superhero squadron idea that he began with Rainbow Sentai Robin, whose team gets a walk-on part in Monster Wars. Ishinomori would pursue the concept further in his tokusatsu shows. Ghost in the Shell is a legacy of the superhero team, while squadrons of magical girls will grace this thread, (and already have). The in-film cyborg creator, Doctor Gilmore, while owing much to Tezuka's Professor Ochanomizu, is a forerunner of Ghost in the Shell's Daisuke Aramaki. The leader of the team, Joe Shimimura, is, more so even than Françoise Arnoul, a prototype of many anime characters to come. His youthful face, and his swept back dark hair, that owes a little to Astro Boy's asymmetric design, will become the template for male action protagonists for the next two decades. His lineage includes Joe Yabuki (Ashita no Joe, 1970), Susumu Kodai (Space Battleship Yamato, 1974), Godo (Space Firebird 2772, 1980), Hikaru Ichijyo (The Super Dimension Fortress Macross, 1982), and Crusher Joe (Crusher Joe, 1983), to name a few. Even Ashitaka (Princess Mononoke, 1997) is reminiscent of him, but then Hayao Miyazaki has a penchant for retro character designs. Other than his cyborg nature, Joe Shimimura is rather dull. He gets his cyborg make-over in the wake of a motor racing accident instigated by the Black Ghost organisation, but that doesn't compensate for his limited personality: he's a straightforward, decisive, black and white, hero protagonist. The films revel in the fighting possibilities of cybernetic enhancement without pausing to explore the ambiguities inherent in a human/machine interface. We will have to wait for Ghost in the Shell for a sophisticated treatment of those issues.

Just some of Black Ghost's military resources. The image conveys both the hyperbole of the films and their cold war atmosphere. There is a strain of absurdity that runs right throughout anime, although there are notable exceptions. Given the preposterous premises often encountered in anime the tongue in cheek approach is probably necessary to carry them off. Cyborg 009 is up front with its hyperbole. Some of the cyborgs, along with their designs, are quite over the top: a telekinetic super genius two year old; a smiling weapons platform whose entire body couldn't possibly store all the ammunition he fires; a fat, Chinese cook who spits flames that melt metal; two cyborg villains that shoot bolts of electrical energy, but whose positive and negative charges cancel each other out when they touch. The weaponry at the disposal of the bad guys is prodigious: the oceans are teeming with cyborg dolphin spies and giant plesiosaurs; while the Black Ghost navy and airforce are vast. The image above nicely illustrates the tone of the films. It also hints at one of their underlying messages - the pointlessness and destructiveness of the cold war then gripping the 1960s world. (The UN Security Council nations are represented in the squad, along with Japan, Germany and Africa.) The Black Ghost himself is neither human nor cyborg - he is all the resentments, rivalries, conflicts and divisions of the cold war world given personification. He cannot be killed or defeated. Or, rather, he can, but will be reincarnated by further strife. With a new cold war between the United States of America and China threatened, the message is a timely one, if given in a childish, light-hearted fashion. Yes, the films are tongue in cheek, frequently and deliberately over the top, and they move at a cracking pace. Each being only an hour long no doubt helps, but none of those qualities can save them from being something of a chore to sit through. Everything is so implausible, so contrived and so piecemeal that they have little tension for action films. The second film is the more entertaining, possibly because the studio had the formula down pat, without having to spend time establishing the premise. The monsters are better, too. Françoise Arnoul / Cyborg 003:

Françoise in elfin pose. Those irises are weird. I suppose they are part of her enhanced vision. A student ballerina in Paris, Françoise was about to crack the big time in her role as Odette in Swan Lake, but for the intervention of war. Injured in the destruction of Paris she is reconstructed as an android by Doctor Gilmore - then working unwillingly for the Black Ghost organisation. (The indication from what I've researched is that each of the nine were killed prior to their transformation. The films skirt around the issue.) She is a reluctant member, requiring persuasion to join in the fight against evil. She and Joe Shimimura are the only cyborgs spared the otherwise obligatory comical character designs. Unsurprisingly, they provide a romantic subplot to the franchise. To my 21st century ways of thinking, Françoise is an anachronism. Her role in the team is determined by her gender in ways that might not have raised eyebrows in 1966 but fails current expectations. She is one of the non-combatant members of the team, along with 001 and 007, both of whom are portrayed as juveniles. (It might be noted that 007 is an adult in the original manga. In any case, being a shape changer he could appear any age he chooses.) The big boys do the hacking and slashing while the women and children stay out of harm's way. She does use a gun once - to blast down a wall in the first film to help the team escape a nuclear detonation. In the climactic battle of the second film she simply disappears - there isn't a single sight of her in the melee. She's there right before it starts and reappears the moment it concludes. Did she cower in a corner? Did the baddies chivalrously avoid fighting her? She occasionally gets to use her superpowers but she is most often seen nursing the infantile, physically helpless 001.

Helena: the first cyborg built by Black Ghost after the cyborg mutiny. Unlike Françoise, she fights. Even as love interest she disappoints. In Monster Wars any tension between her and Joe evaporates the moment the treacherous, later repentent, Helena/Cyborg 010 appears. Indeed, from that moment Françoise becomes merely a background ensemble character. Helena proves herself more assertive and more proactive. Mind you, she will ultimately conform to the tragic female role, when her tender feelings for Joe cause her to repent, then sacrifice herself so that he may escape the Black Ghost's clutches. Helena also gets the best musical themes of the films - a sequence that starts off as a cheesy version of mid 20th century Hollywood soundtracks complete with wordless female chorus then, somehow, transforms into a sequence redolent of the opening section of Pink Floyd's Shine On You Crazy Diamond on the way to some aching chords that suggest Arvo Pärt. Don't worry, though, the cheesiness will prevail, as it must in these films. Cyborg 009 frequently references the James Bond franchise. That's obvious in the cyborgs' naming conventions and also apparent in the shared cold war themes. Other parallels appear. Civilian Joe dresses in cliche spy clothing, while Cyborg 007 is indeed British, though the antithesis of Bond. Françoise is meant to be the Bond girl, but, in these instance, is decorative rather than instrumental. She is the token female in a show about boys, just as 005 and 009 are token representations of native Americans and Africans. Marks for trying, though. Hence, why I've classified her as a proto-beautiful fighting girl. Other than the manga aesthetic, she could be any one of thousands of female characters that litter storytelling aimed at male audiences. That amazing anime trait where female characters take over and run the show is happening elsewhere at this time, in an entirely different anime genre. Between the release of the two Cyborg 009 films, the same studio - Toei - would start the next revolution in anime after their own pioneering films and Osamu Tezuka's introduction of manga aesthetics and themes.

Left holding the baby. Not surprising, really. Ratings: Cyborg 009 - not really good; Cyborg 009: Monste Wars - so-so. Resources: ANN: Cyborg 009; Cyborg 009: Monster Wars The Font of all Knowledge The Tokusatsu Network: Shotaro Ishinomori: The Man Behind Masks **** This is the last of the "proto" posts for this project. As alluded to above, the next instalment will begin the female as protagonist exploration proper. It also marks a shift away from anime I've seen previously to first time viewings, which will slow down my reviews. Some of the series ahead of me have fifty or more episodes. On the flip side of that coin, some essential series simply aren't available in their entirety, which will have implications for my reviews. Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 31, 2018 6:09 pm; edited 2 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

All times are GMT - 5 Hours |

||

|

|

Powered by phpBB © 2001, 2005 phpBB Group