The Mike Toole Show

Reed All About It

by Michael Toole,

How much does an anime studio cost? I'm not talking about the costs involved in founding one, securing space and resources, and hiring workers—I mean, how much cash would you have to throw down to buy an existing studio, one with a fairly decent portfolio of shows? Arriving at that figure can be a hell of a headache, but a good indicator might be a studio's asset valuation – Tokyo Movie Shinsha, for example, are valued at 16 billion yen . Or maybe a good barometer is the amount of capital that the studio possesses. Even after their heavy tumble when the anime boom snapped, Gonzo still have 3.3 billion yen in wiggle room, or about 30 million bucks. Satelight are capitalized at 275 million yen, or 2.8 million dollars, and upstarts WIT Studio, the Attack on Titan people, started off with just 30 million yen—three hundred thousand bucks. Who wants to start saving up?

The reason I'm pondering this question is because a vaunted old studio, one with decades of experience, a production house that turned out pioneering hits for a good 20 years, got sold off in 2009. The parent company, a toy manufacturer, held a controlling interest, but sold their whole share to the company president, effectively making the studio a private, employee-owned business. That total amounted to $840,000. You could buy a fairly decent single-family house in my neighborhood for that. The name of the studio? Production Reed.

It's kind of a pain in the ass to quickly find and sort information about Production Reed, simply because they've only been called that for 5 years. Before that, they were called Ashi Pro, and a-ha! Now I can see some of you starting to nod slowly, images of pink-haired magical girls and kinetic combining super robots twinkling in your eyes. Ashi Pro was founded on Christmas Eve 1975, and got straight to work on a variety of projects, from robot shows like Blocker Corps and Gingaizer to family cartoons like Josephine the Whale. But these were all joint affairs that Ashi didn't have a major stake in; Blocker Corps and Gingaizer were Nippon Animation shows, and Josephine was produced in partnership with the generally great and sadly long-gone Movie International Corporation, or Kokusai Eigasha. These two companies got along well, and so collaborated on Tales of La Mancha, Monchi-chi (yes, those weird toy monkeys!) and Baldios, the latter of which I've touted in this column.

Ashi Pro finally sallied forth on their own with the super robot adventure GoShogun, which I've covered in considerable detail here. The series, anchored by the duo of director Kunihiko Yuyama and scribe Takeshi Shudo, was filled with surprisingly intelligent twists, like a set of bad guys who gradually shift allegiances to the good guys and an entire episode that's a send-up of Gundam and the “real robot” trend in general. GoShogun's surprising intelligence and creativity didn't make it a mega-hit, but it still makes appearances in the Super Robot Wars games, so it hasn't drifted out of the otaku hivemind. But the series is really just a prelude to Yuyama and Shudo's long and fruitful partnership.

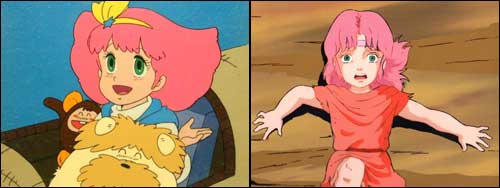

Ashi Pro's signature hit would come the following year, as they boldly challenged Toei Animation in a category that the larger studio had owned completely up until that point—the magical girl genre! Yes, that's right: every single prior magical girl work, from prototypes like Sally the Witch and Secret Akko-chan to later, more refined fare like Flower Angel Lunlun and Majokko Megu-chan, came from Toei. Even though some of these shows were quite popular, no competitors had thought to reverse-engineer the formula—not until Ashi Pro. But Ashi's Magical Princess Minky Mono didn't just broaden the field for magical girl adventures—it radically increased the genre's vocabulary, cementing now-familiar tropes like chattering animal buddies, a more active, action-oriented heroine, numerous transformation sequences, and special vehicles and accessories. Prior shows had some of this stuff, but Minky Momo made it all part of the standard template. Pierrot came hot on their heels with their own Creamy Mami, but Ashi Pro was the first studio to challenge Toei for majokko supremacy.

You know, I'm half-convinced that part of the reason that anime didn't go big in the English-speaking world until the 1990s is because of titles—not the shows themselves, the titles-- like Minky Momo and Creamy Mami. Sure, we know they're fun shows for the whole family, but try convincing a stranger to watch something called “Creamy Mami” or “Dirty Pair.” Much of Europe avoided this trap by simply calling Minky Momo's title character Gigi. Oddly enough, this is almost certainly Harmony Gold's fault—they dubbed and marketed the 90-minute Minky Momo OVA, La Ronde in My Dream, under the title Gigi and the Fountain of Youth. This didn't lead to a deal for the show in America, but the series was successfully sold in other territories, often using the Gigi adaptation as a jumping-off point. Don't miss the nightmarish incantations of Minmei-era Reba West as Gigi herself. Did you know that Harmony Gold president Frank Agrama has a daughter, and her name is Gigi? What a coincidence!

Maybe I oughta talk about what Minky Momo is and why it left such an impression. Momo herself is a fresh-faced, pink-haired 12-year-old girl who happens to be princess of the dream kingdom of Fenarinarsa. The kingdom, which relies on the hopes and dreams of mankind to keep it vital, is threatened thanks to the shortage of hopes n’ dreams on Earth. So Momo is dispatched to Earth to help good people regain their dreams, and takes up with a kindly but childless couple who run a pet store. With the help of her monkey, dog, and bird pals (spot the Momotaro reference!), Momo uses her magical stick (yeah, it's just called the Minky Stick) to transform herself into a slightly older pink-haired girl with relevant occupational skills. Is there a sick or hurt animal? Momo waves her stick and becomes a veterinarian. Lost little kids or delinquents on the loose? Officer Momo will sort things out. Sports team stuck in Mudville? No problem, Momo will stand in for the coach! The show's McGuffin is the crown of Fenarinarsa; every time Momo does enough good deeds and brings hope to the people, a jewel appears on the crown. Once twelve jewels have appeared, the kingdom will be saved.

You can see why this setup would be awfully compelling for little girls watching at home. Momo has cute pets who can talk to her. Momo has nice foster parents who don't treat her like a baby or a brittle porcelain doll. Best of all, Momo has this weird car/RV combo that can fly around, and magical powers that let her do any job she wants, without having to fill out applications or sit for interviews. It's a standard “can't I just skip the crappy parts of childhood?” fantasy, writ in huge, compelling brush strokes. But Minky Momo wasn't just attracting its target audience. The show's airing was contemporaneous with the rise of lolita manga, comics for adult men featuring idealized—and almost always sexualized—young girls. Consequently, Momo's adventures had an unforeseen target audience—“men of a certain age,” you might say. Thanks for nothing, Hideo Azuma!

But it isn't as if Minky Momo's older fans had nothing to latch on to. The show's animation was quite good for TV, anchored by Toyo Ashida's character designs. Hey, didn't Toyo Ashida also do some of the character designs for his own Fist of the North Star TV adaptation…? HEY, WAIT A MINUTE

You know, I always wondered why Lin's hair was sometimes pink in the TV version, when it looked so much darker in the original manga. Anyway, Minky Momo wasn't afraid to be smarter than its target audience—there's an entire episode that's a wry parody of the aforementioned GoShogun, with Momo squaring off against a shadowy mafia group using a super-duper combining robot. The way the show wraps its main story arc is surprisingly brutal—if you're watching Minky Momo now (and it wouldn't shock me if you were—it looks like most of it is on Youtube, albeit not exactly legally), you might wanna skip the next couple of paragraphs.

Minky Momo's ending is actually quite famous. Late in the series, Momo's magical powers disappear, her mission left unfulfilled. She saves a toddler from getting run over, but is herself struck and killed by a runaway truck full of toys. This wasn't just Shudo being a bit sadistic—just after the prior episode, 45, had wrapped production, toy sponsor Popy pulled their backing, griping about how the series wasn't shifting enough Minky Momo dolls and playsets. (If you want one, it's right here!). The gang at Ashi Pro weren't happy about this—the cartoon's divergent target audiences were combining for a strong 10% ratings share, which had already earned the series an extra 13 episodes beyond the original order of 50, and it wasn't their fault the toys were crappy. Yuyama and Shudo reacted viscerally, killing Momo herself off using a goddamned toy truck. That wasn't all, either—Shudo wrote a terse essay entitled “Farewell to Minky Momo” about Popy's withdrawal and his reaction, which was published in the late, great OUT Magazine. This was back when you could actually write disparaging shit about the anime business—you'd be hard-pressed to find that kind of commentary in the Japanese anime magazines nowadays.

Despite that genuinely shocking bit of business, Ashi Pro still had some money in the budget and episodes to complete. The team reacted well; after the requisite clip/recap episodes to buy a bit of time, the viewers learned that Momo was reborn as the nice couple's real, human child, and would have her own hopes and dreams to defend now. But what fans and pundits remember is the truck episode; to me, it sits right next to Yoshiyuki Tomino's hilarious, relentless overuse of the same stock footage of the sponsor-mandated G-Fighter in Mobile Suit Gundam as an example of sharp animation talent rebelling against their inept toy company backers.

When I started writing this piece, I naturally checked on the Wikipedia article to see what I'd be up against. That article makes an interesting assertion, stating that Ashi Pro/Reed is most famous for their magical girl productions. Now, hang on a minute. Minky Momo is most definitely Reed's most famous character, but she's flanked by the likes of Magical Angel Sweet Mint and Floral Magic-user Mary Bell. Sweet Mint definitely looks the part, a teen girl with teal hair and a magical bird pal, but Mary Bell is seems to skew way younger, featuring pint-sized characters and even simpler stories. These shows still look really nice, but have they stood up to the test of time? I'm not so sure. Maybe I'm just showing my age.

If you ask me, Ashi Pro's legacy is all about the robots, man. They got started with GoShogun, they moved on to Dorvack, a mecha show that we've only really seen on these shores in the form of certain GoBots, and then there's the fairly wonderful Dancougar, a series that features animal-themed transforming robots, an alien invasion/occupation plot, and great character and mecha designs that are gradually subverted by the show's steadily shrinking budget. Dancougar is definitely one of those shows that wasn't really funded well—as the series goes on, episodes start to look worse and worse, and there are some real, slideshow-style, “ah crap we ran out of money” sequences in the final story arc. Some anime was like that in the 80s.

Ashi's other long-running mecha franchise of the 80s was Machine Robo. I could talk about this goddamn thing for days—it's a cheerfully nutso kung-fu tale of the old west, as a young scion and his allies fight evil and search for a powerful artifact on the far-flung planet Kronos. The twist is, hero Rom Stol is a robot, and the heroes and villains are filled out by Bandai's Machine Robo toy line. This presents some interesting challenges as the series progresses; there are only a handful of truly important characters, but dozens of Machine Robo toys, which must all appear thanks to contractual obligation. So a lot of them show up once, then die pretty much instantly, or just plain never appear again. Squint, and you can see some of ‘em in the background of the ending.

Machine Robo's other bit of trivia is that Central Park Media licensed it by accident, forgetting to turn it down when it was offered in a package deal with the more attractive Dancougar. This detail is pretty well-known these days, but I never tire of mentioning it. CPM gave it the ol’ college try with Machine Robo, but we only got the first third of the series. There's a sequel, entitled Battle Hackers, which is reportedly pretty awful. I'd like to see it.

I'd love to go into great detail about Sonic Soldier Borgman, Ashi Pro's next mecha/SF hit, but I just plain haven't seen much of it. All I can tell you is that the OVAs, released by ADV Films in the mid-2000s, are fun to watch but hard to follow thanks to the lack of context. I also know that, after Machine Robo's Leina Stol graced magazine covers and even got her own spinoff show, anime's next “it” girl was Borgman's own Anice Farm. It's interesting how fans will devote so much energy to fixating on one character like that. Evangelion's Rei Ayanami really commoditized the “premium girl” angle of anime productions, but she was really just walking the trail blazed by the likes of Anice; I still sometimes bump into forty-ish fans at conventions who carry a torch for her, and they're still churning out Anice-related merchandise like figures.

The 90s were an exciting time for Ashi Pro. They started the decade right, with a second helping of Minky Momo that's only tangentially related to the original. It looks really nice, and features then-breakout star Megumi Hayashibara as Momo, and even manages to retain the show's weird intelligence and self-awareness—runaway trucks, in this case, are treated as something of a running joke, as Momo dodges one not once but several times. But the newer show seems a bit more wistful and cynical, even pessimistic at times. I've seen theories about Ashi quietly targeting the original Minky Momo at lolicon fans, a theory that studio head Toshihiko Sato has denied, but it wouldn't shock me to learn that the studio made the follow-up with the secondary older audience in mind. Ashi Pro then worked on Macross 7, which is probably better off being broken down in a Macross-specific column, and then created an anime adaptation of Zorro.

Yep, Zorro, Johnston McCulley's black-clad, rapier-wielding avenger of the poor and disenfranchised in old California. It only makes sense—Zorro's been adapted many other times, and is one of the earliest costumed heroes to really make an impact in 20th century literature. What weirds me out a bit is the way Zorro looks—the character Don Diego de la Vega is described by McCulley's prose as a high-class local gent with family back in the old country, and most every adaptation depicts a character that's obviously latino, or at least dark-haired. Even Douglas Fairbanks, the original big-screen Zorro, sports this look. So it's a bit jarring to see Ashi Pro take the “blond Tuxedo Mask” approach to Zorro.

Zorro suffers from some common afflictions—stock footage abuse, one-dimensional villains, a dumb kid sidekick—but it's a fun take on an ages-old international classic. I like Zorro's plucky girlfriend Lolita, who scorns Diego but loves the masked hero, and is pretty handy in a fight herself. Zorro was dubbed in English, not to mention several other languages, but it somehow never made its way to American television. This is probably due to legal issues; technically, the character of Zorro is now in the public domain, but McCulley's descendants run Zorro Productions, a company that's been pretty hawkish about defending the character from what it sees as unauthorized usage. I wonder how the anime deal got made, originally. Were Zorro Productions on board? Or did Ashi Pro just go ahead, make the adaptation, and hope that nobody would notice? Don't laugh, that's pretty much how Lupin the 3rd got made!

Ashi Pro has had some interesting experience with weird, cross-pacific licensed stuff. I've written before about the peculiar history of Machine Robo toys and where they intersect with the cartoon; my favorite example is Battle Flex, series hero Rom's tank, which is actually based on an all-American toy. Beyond that, Ashi produced not one but two Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles OVAs. I guess it only makes sense that the famous turtle heroes, who use ninjitsu, would have hit Japan at some point. The original Fred Wolf TV series didn't hit Japanese airwaves until the mid-90s, but it was popular enough to spawn a pair of OVAs. Feast your eyes on this hotness.

See, in these episodes, the Turtles can use special gems to mutate into super-buff versions of themselves. And when the stakes get really high, the four heroes can combine into the almighty Turtle Saint! It's a damn shame these OVAs didn't get released stateside—they're dumb as hell but light and funny, and to me they do a perfectly acceptable job of replicating the old cartoon's weird humor. But these TMNT OVAs aren't the only Japan-only version of beloved western cartoon characters. There's also the Transformers.

Ashi Pro didn't do the long run of Transformers shows based on the old Marvel/Sunbow cartoons—stuff like Headmasters and Super God Masterforce were handled by good old Toei Animation. But Ashi did handle Beast Wars II and Beast Wars Neo, a pair of follow-ups to the Canadian-animated CGI Beast Wars series. These two shows are some of the only remaining Japan-only Transformers fare that haven't gotten an official release elsewhere in English. Even that weird old Scramble City OVA is out there. All I can really tell you about these shows is that I find it hilarious that the upgraded version of Convoy (or Optimus Prime, as we know him) is known as Big Convoy in Beast Wars Neo. That's him up there. Does he look like a convoy to you? I'm not really enough of a Trans-fan to analyze these series, it just seems incredibly weird to me that they never got shipped over here. Instead, American Transformers nerds had to wait a few years for Studio Gallop's Transformers: Robots in Disguise. Some sort of release by Shout! Factory seems like it would be a no-brainer, but we'll see—for many years, Beast Wars II and Neo weren't even available on DVD in Japan.

Reed kept at it for several more years, turning out the F-Zero anime, Ultra Maniac, and an unusual follow-up to their classic Dancougar, Dancougar Nova. But in recent years, they've quietly dialed down their ambitions. They're still extremely active animation subcontractors – they've worked on fare like Black Butler and Kobato, and seem to partner up with A-1 Pictures a lot these days. They even worked on Attack on Titan, but I'm pretty sure that every single animation studio in Japan and South Korea has done some work on Attack on Titan. That vaunted partnership of Kunihiko Yuyama and Takeshi Shudo would eventually move away from Ashi Pro; you might know them better now as the guys behind the first several seasons of Pokemon. Shudo, who created Minky Momo, occasionally remarks on ideas for a third TV anime based on the famous magical girl, but that has yet to materialize. The studio promised a new Momo at the Tokyo Anime Fair in 2009, but we've seen nothing just yet. I have a feeling they're just waiting for someone to help them pay for it. In the meantime, Production Reed set up a successful Minky Momo stage show in 2010.

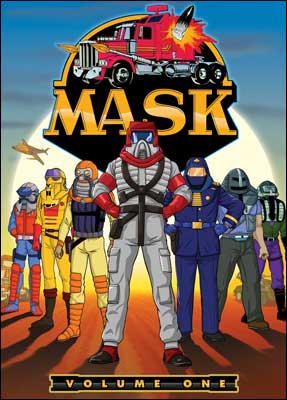

But what got me thinking about Production Reed? (See, the deal is, ashi means “reed” in Japanese. Simple, right?) It wasn't just Minky Momo, or Machine Robo, or any of the other usual suspects. What got my attention was seeing the studio's old name pop up in the credits for this thing, which I bought at the used DVD store last week:

Checking out a couple of episodes of this happy, toy-tie-in mess was an interesting experience. The show kind of sucks, and the vehicle designs are openly unfeasible and hilariously ugly, an observation made stranger by the fact that the show's mechanical designs were handled by Shinji Aramaki. I'll assume he was basing them on existing toy designs. He also did character designs, an unusual duty for him. Anyway, Ashi kicked in some key animation on the second season of this series. Nothing sensational, just a dumb 80s toy cartoon that's remembered a bit too fondly by its fans, judging by the voluminous articles on the web about it. But I kept noticing weird things about the show, like the fact that all of the storyboarding team was Japanese (does this, technically, make it anime?) while all of the writers were western. Oh, and the writers? More than thirty of them. Compare the 65-episode M.A.S.K. to the 63-episode Minky Momo, which had fewer than ten scriptwriters. Huh. And then there's this:

Check out the series heavy, there. I like how Miles Mayhem wears a tie to work. Sowing discord, stealing stones and breaking bones, and trying to take over the world—but hey, it's still just another day at the office, right? Ex-Onion and current The Dissolve film critic Tasha Robinson once pointed out something interesting about the show's OP. Go and watch it, and pay attention to the final lyric.

Are you back? Good. What do you think that last bit was? You might've noticed that the above link wasn't just to an embedded Youtube, but to Robinson's livejournal, where she polled followers on what the hell that lyric was. Nobody could agree. For years, I thought it was “’MASK! Always riding hard on VENOM's trail / ‘cause he's a laser ace / anywaaaaaaay.” But that can't be right, can it? Alright, I think I'm done being stupid.

As I noted above, Production Reed are still very much in the anime game. But they've backed off from producing their own works; their most recent original project is a toy tie-in called Bakujū Gasshin Ziguru Hazeru, from last spring. Ziguru Hazer? Jiggle Hazel…? I haven't been able to find these shorts anywhere. Anyway, it's fascinating to me that a company that's had a significant influence on the anime business quietly traded hands for the kind of money that could feasibly be raised by a sufficiently compelling kickstarter campaign or a big scratch ticket win. You'd think the rights to publish Minky Momo alone would be worth more than that. But then again, how are you gonna capitalize on an old property like Momo in this day and age, exactly?

So let me pose the question, readers: how much is your favorite anime studio worth to you?

discuss this in the forum (33 posts) |