Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girls index

**** Beautiful Fighting Girl #37: Emiya Tachi, aka the Princess Primrose of Kukritt

A Time Slip of 10,000 Years: Prime Rose Synopsis: Thread A. In an historically retrograde future Emiya is the adopted daughter of Kinkrittean merchants prospering under the hegemonic rule of the Gromans. When her lover is enslaved, then executed by the Gromans Emiya vows revenge against their Governor Pilar. Problem is, in order to curry favour, her parents have promised her in marriage to the very man she seeks to kill. Running away from home she is taken in by an old warrior who teaches her to become an expert sword fighter. Turns out the old man is much, much more than he seems, and when a mysterious outsider foments rebellion, Emiya unexpectedly finds herself in its vanguard. Thread B. Some time in the not too distant future a gigantic military satellite splits in two and plummets to earth, with one half annihilating Dallas, Texas and the other half likewise destroying Kujukuri Beach, Chiba Prefecture. Military scientists, suspecting that the inhabitants of both cities had been transported far into the future, send time patrolman Gai Tanbara to investigate. He discovers the citizens of the two cities have morphed into two societies, the dominant Gromans (ie Romans) and the subjugated Kinkritteans (ie Christians). Himself enslaved, Gai leads a revolt against the overlords, willingly assisted by a young woman of exceptional fighting talents. Production details: Premiere: 21 August 1983 (TV special) Director: ANN lists brothers Osamu and Satoshi Dezaki with Naoto Hashimoto assisting; the Anime Encyclopaedia has Osamu Dezaki and Naoto Hashimoto; while the Tezuka Osamu official website credits Tetsu Dezaki assisted by Naoto Hashimoto. I'm inclined to accept the official website. There Tetsu Dezaki is identified with the Magic Bus studio, which suggests that Tetsu = Satoshi Dezaki, who founded and was director for Magic Bus. Take your pick. Studios: Tezuka Pro, Magic Bus and Nippon TV Original manga: Osamu Tezuka's Prime Rose published in Weekly Shonen Champion from 09 July 1982 to 03 June 1983 Character design: Osamu Tezuka Screenplay: Keisuke Fujikawa Storyboards: Noboru Ishiguro Art Director: Shichirō Kobayashi Animation Director: Keizō Shimizu Music: Yuji Ohno

Comments: If you've been following this thread you may understand me when I describe this obscure and oddball TV special as part Cleopatra (directed by Osamu Tezuka and Eiichi Yamamoto), part Star of the Seine (directed by Satoshi Dezaki and Yoshiyuki Tomino) and several parts ridiculous (both intentional and otherwise). Tezuka gives us faux-Roman overlords, familiar characters from his "star system", ribald fanservice and obligatory pricking of pomposity. For his part, Dezaki supplies a variation on the young woman who, ignorant of her regal birthright, takes up a sword and fights against injustice. It might sound good in theory, but Prime Rose falls flat thanks to the various parts working against each other, a plot that lacks discipline, a hero and heroine who don't work as a pair, and a series of logical and emotional non-sequiturs. Watching this in the wake of Daicon IV has been illuminating. I've long thought of that short film as the moment the fanservice floodgates open, but I didn't expect something like Prime Rose so soon from Tezuka or Satoshi Dezaki. (The day after, to be precise.) But then, I should have remembered Cleopatra along with A Thousand and One Nights or even Marvellous Melmo and Princess Knight. Emiya's skimpy battle gear - parodying Roman gladiators - seems at odds with her serious and feisty personality. Unlike Daicon IV, where the sense of fun and the intentional absurdity make light of the sexualised presentation, Emiya's outfit is tacky. I could well imagine her declaring it ridiculous and an insult to her pride. Dissonance of various sorts occurs throughout the anime, whether fanservice or otherwise. Another fanservice example is the execution of Emiya's lover Taro (see bottom-left image above). A sombre moment as Emiya witnesses Taro pierced with arrows is undone by a gratuitous panty shot. It's as if Tezuka has a destructive impulse where any serious event must be undermined. Emiya herself fails to convince. Initially helpless, she is rescued from a ravening Groman soldier by Gai. Devoted to Taro, she is likewise impotent as he is killed on Pilar's order. When the narrative moves to her domestic situation, she demonstrates her wilfulness, petulance and selfishness. Not an appealing personality, she earns sympathy points thanks to her adopted parents' fawning hypocrisy and Pilar's sinister propositions. The anime treats her cruelly, as Tezuka is wont to do with his female characters. At various points she's pinned down, strung up, tossed out and thrown aside. That all said, I loved her responses to PIlar's persistent invitations to dance. The most jarring development occurs upon her discovery that she is the rightful queen of the downtrodden Kinkritteans. In an instant she is transformed from indignant and vengeful child to noble and dutiful leader. Her declaration that, "as queen of Kukritt, it's only natural that I fight for my people," simply doesn't wash. Something similar happens in her relationship with Gai. One of the oddities of the plot is that the two leads don't interact all that much. Emiya and Gai each have their own parallel narrative that intersects with the other from time to time. One moment Emiya loves Taro; the next she loves Gai. Such outcomes are to be expected from action stories, but the execution is, like most everything else, perfunctory and lacking in emotional conviction.

Top: Gai Tanbara (and his irksome brother Bunretsu) Middle: left - Emiya's adoptive father greets Pilar; right - the big bad, Death Mask (Note the shared blindness in one eye) Bottom: cameos from Hollywood and Tezuka's "star system" Other characters are similarly disappointing. Gai, like many anime action heroes before him, refuses to allow his heroic nature to be sullied with any sort of sophistication, wit or humour. Despite his avowed love for Emiya, he walks out on her. Not even able to tell her to her face, he leaves a note saying, "But this is goodbye. My next job is waiting for me." How lame! In traditional Toei and Mushi fashion, the anime compensates for Gai's wooden personality with a designated comic relief character in the form of his pestiferous younger brother, Bunretsu. He's the noisy, nudge-nudge-wink-wink knows too much for his years (see image above), trouble-inviting irritation straight out of a Go Nagai show. Good anime doesn't need stupid humour every three minutes. Pilar mostly succeeds as an arrogant and vicious villain until he has a totally out of character road-to-Damascus moment. My satisfaction at his resultant skewering wasn't due to seeing a villain get his comeuppance so much as schadenfreude at his demise being brought about by an inchoherent change of mind. That'll learn him. The real big bad - a rogue satellite AI known as Death Mask - is even more implausible than the other characters. Why such a device would be built with a sadistic personality is never properly explained, nor its penchant for monument building, nor its ability to create weapons out of thin air. And I have to mention the cockroach attack. Yep, giant cockroaches come out of nowhere and bring about the demise of the Gromans. Makes about as much sense as anything else. Prime Rose does have good points. Emiya is a strong character, if not always convincing. Setting the weird gladiator strapping to one side, she has an attractive design, as the top image attests. Tezuka's ever optimistic worldview is appealing, while his humour - despite its tendency to bathos and the tiresome brother - has a sort of dopey charm. The narrative doesn't hang about - which admittedly contributes to the abrupt changes in behaviours - so the telemovie isn't dull. Visual short cuts are in evidence, but Prime Rose isn't afflicted with the obvious financial shortcomings of the later Mushi producttions. It also avoids, probably thanks to Dezaki's direction, the jarring stylistic jumps of Tezuka's earlier films. Composer Yuji Ohno scavenges melodies from popular songs from the seventies, channelling Simon and Garfunkel, Tony Orlando and Led Zeppelin with just enough variation to avoid having to pay royalties. It works quite well. Rating: Not very good. A poorly constructed narrative, unconvincing characters and bizarre design choices overwhelm any positives this telemovie may offer. Resources: ANN Tezuma Osamu official website Tezuka in Engish The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle

Gai escapes from the heroine. **** I've only watched 6 episodes out of 52 from the next anime, so it will be 2-3 weeks until its review. In the meantime all the best for the holiday season and the new year. Last edited by Errinundra on Tue Feb 15, 2022 4:21 am; edited 4 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl #38: Alice

Alice in Wonderland Synopsis: Alice, the younger daughter of a well-to-do Victorian era family escapes from her humdrum world by imagining herself in Wonderland. There she experiences things both unsettling and wondrous, meets eccentric characters, and discovers time and again that "logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead" to quote Grace Slick. One way or another Alice always manages to prevail before being transported back to her comfortable and reassuring life at home. Production details: Premiere: 10 October 1983 Source material: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There and The Hunting of the Snark by Lewis Carroll Director: Shigeo Koshi and Taku Sugiyama Studio: Nippon Animation and Apollo Film Screenplay: Niisan (Fumi?) Takahashi; English script Marty Murphy Character Design: Isamu Kumada and Kazuko Nakamura Art Director: Satoshi Matsudaira Music: Reijiro Koroku for Nippon Animation; Christian Bruhn for Apollo Film Note: Even though all 52 episodes have been dubbed into English (and can be viewed on YouTube) finding information about the dub is nigh on impossible. The only mention in the episode credits is Marty Murphy, while ANN and MAL have nothing, and IMDb has the English actor Natalie Ogle playing Alice. I'm convinced the dub was done in England: there's Natalie Ogle; the plummy accents are perfectly delicious; and I'm sure I heard a pre-famous Alan Rickman from time to time. Apollo Film were a division of the Viennese company Jupiter Film GmbH specialising in German language releases of shoujo anime. Nippon Animation had tapped into a gold mine adapting Western classic stories and, sure enough, it was broadcast throughout Europe, the Middle East, India, the Philippines and, at least Canada that I can verify in the Anglosphere.

Compare the characters from the anime with John Tenniel's illustrations from the original editions. Comments: It comes as no surprise that this survey would stumble across Alice in Wonderland at some point. Alice is arguably the closest English language analogue of the shoujo heroine or, even perhaps, the mahou shoujo. Without mentioning the obvious, and at times highly creative, anime revisionings (see Rebecca Silverman's ANN article, Alice in Anime Wonderland), I can see Alice's influence in Secret Akko-chan and her descendants who aren't innately magical but access the magical realm through some device or portal. Akko-chan not only shares Alice's knack for travelling through mirrors, her name Atsuko Kagami tells you so. (The name was later used for the heroine from Little Witch Academia - thanks Alan45.) I also see her, sometimes obliquely, in anime as diverse as Serial Experiments Lain, Spirited Away or even Mardock Scramble. Masafumi Monden (via Wikipedia) describes Alice as performing the shoujo ideal, being "sweet and innocent on the outside, and considerably autonomous on the inside." With her flouncy dresses, petticoats and pinafores, and the mid-Victorian setting (in his depiction of the characters original illustrator John Tenniel lampooned public figures of the time) Alice is also a major inspiration for lolita fashion in Japan. The parallels extend somewhat further even, to lolicon. Lewis Carroll (the pen name for Charles Dodgson) was, in addition to his literary pursuits and his day job as a mathematician. a photographer notable for his images of young girls. You can view a selection here from Wikimedia. There's something proto-moe in the image of Alice Liddell as the "Beggar Girl". (The story of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland began with Charles Dodgson telling it to the three Liddell children on a rowing trip on the Isis - the Thames in Oxford. Ten year old Alice asked him to write it down, which led to its eventual publiclation. While she provided the name for the protagonist, Dodgson claimed and contemporaries attested that Alice Liddell wasn't the inspiraton for the character.) Coincidentally, the first hentai OVA, Lolita Anime, began its release sequence whilst Alice in Wonderland was airing on TV. The anime differs from its sources in several ways. Structurally, the TV series has 52 stand alone episodes, each with a problem and a resolution, while the two novels are rambling, non-sensical streams of events. Alice enters Wonderland at the start of each episode and leaves at the end. This effectively removes the underlying threat of entrapment underpinning the novels. The tension is further diluted by significantly downgrading the menace in such characters as the Queen of Hearts and Jabberwocky. The Queen of Hearts may be the series antagonist and she still shouts, "Off with their heads!" but she's now an endearing soul who is the butt of fat jokes, both beyond and within earshot. She turns out to have a soft centre - no one is decapitated - and by the latter part of the series has come to rely on Alice in place of her incompetent minions. She's probably the sanest person in Wonderland. And full marks to the anime for not conflating her with the Red Queen or the Queen of Spades, both of whom get their moments of madness. The Jabberwock, for his part, is just a grumpy coot who wants to sleep in peace when he's not pursuing his favourite pastime, cooking. On more than one occassion he helps Alice out.

"Curiouser and curiouser," thought Alice . You can see from this that the anime is expanding enormously the role of the secondary characters. In the novels most of the characters appear in a single chapter, or maybe two, before Alice moves on. At an extreme level Jabberwocky only appears in a nonsense poem read and discussed in Through the Looking Glass. The anime is more of an ensemble piece where the members of the very large cast make regular appearances. The size of the cast is no problem: they need no introduction; we already know them. A running gag, that doesn't work, plays with this notion: Alice must keep re-introducing herself to the same characters over and over. Characters with much expanded roles in the anime include the hookah-smoking caterpillar who becomes Alice's most trusted ally and her go to Mr Fixit, the boorish Humpty Dumpty and the bumbling, nervy White Rabbit. Benny Bunny - Alice's mascot pet rabbit - is the only recurring invented character. Alice in Wonderland blends the events of the two novels quite haphazardly. All, and I mean all, the iconic characters appear at some point in the series, though in quite different contexts much of the time. Another running gag is the White Queen's obsession with croquet - in the middle of an otherwise unrelated scene someone may be struck by one of her wayward croquet balls. The anime preserves the surreal imagery and the absurd juxtapositions of the original, but largely abandons the linguistic and logical game playing that makes the novels so endearing to older readers. It (and I'm only familiar with the English dub version) also makes more explicit the psychological mechanics behind Alice's trips to Wonderland - her boredom with her family life - but presents her fantasies sympathetically rather then condemning them. Alice herself makes a successful protagonist. The anime can't reproduce the stream-of-consciousness point of view of the novels, but this Alice is more active, more resourceful and more critical of events than her literary counterpart (not to say that the original is lacking in these qualities - the anime is, after all, not as ambitious as the novels). She's also rather less ugly than John Tenniel's original illustrations of her. And, while many of the characters still find her preposterous, important ones are won over by her. By about the half-way mark, though, the anime has pretty much exhausted its source material (though it saves same important scenes for the end of the series - in particular the chaotic feast with the Red and White Queens that concludes Through the Looking Glass). Thereafter the anime sets up puzzles or problems for Alice to solve, or has her off on adventures. An example would be the episode where stray sheep from Australia (along with a giant red kangaroo and its joey) have found their way via subterranean passages into the castle belonging to the Queen of Hearts. Not one to miss an opportunity, the Queen has them working sweatshop hours knitting jumpers for the coming winter (referencng the knitting sheep in Through the Looking Glass). Overworked and homesick the sheep make shoddy jumpers that fall apart to the touch. Alice uses the shortcut to visit Australia and help extinguish a bushfire. On return she negotiates improved working hours for the sheep and a fair wage for the kangaroo who has started a taxi service using her pouch. The episode is quite topical. Earlier that year Australia elected Bob Hawke, a union leader famous for his negotiating skills, as prime minister just 23 days after its worst ever bushfires to that time. The mash-up of the knitting sheep from Through the Looking Glass, the Queen of Hearts from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, the Australian bush and union negotiations works surprisingly well in a series that revels in the absurdity it inherits from Lewis Carroll. Nonetheless, the second half of the TV series has less Lewis Carroll and less interest. Many of these episodes extol juvenile friendly virtues such as friendship, loyalty and courage, thereby unwittingly and ironically mimmicking the Duchess whose obssession with finding morals in every situation Carroll lampoons savagely. Don't be put off - thanks to the continued whimsy and the toffy, but endearing English dub, even these episodes are an easy watch. Rating: flimulous - that is, somewhere between mimsy and frabjous, though, correctly speaking, there's a only a conjunction and two spaces between them.

Alice proves her mettle when crow pirates abduct her. Source material: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland via Kindle Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There via Kindle The font of all knowledge ANN, recommended reading Rebecca Silverman's Alice in Anime Wonderland IMDb The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Discogs (re Apollo Film Wien) Last edited by Errinundra on Tue Feb 15, 2022 4:22 am; edited 5 times in total |

|||

|

|||

horseradish

Subscriber SubscriberPosts: 574 Location: Bay Area |

|

||

|

I've been curious about this Alice in Wonderland adaption for a while. I had the impression that it was a strictly faithful adaption considering the sparse description Rebecca's article and the Anime Encyclopedia gave for the series. Rarely hear about a children's series containing an episode focusing on labor rights. A bit odd that a Victorian child with a carefree life would care enough about such issues.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

Given the gulf between mimsy and frabjous, rating it as flimulous leaves me plenty of wiggle room. The series is faithful insofar as it has all characters from the books, no matter how minor. As I said in the review, some are expanded in scope and some are made less threatening - Jabberwocky and the Queen of Hearts being examples of both processes. Most events from the books are included, but often in completely different contexts. The first ½ dozen episodes or so follow the beginning of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland fairly closely, but things start to loosen up thereafter. It still retains the non-sensical narrative tone of the books, but prefers to give each episode a start, middle and end. Mind you, quite a few of the episodes take odd turns mid way through. Last edited by Errinundra on Thu Jul 22, 2021 4:11 am; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

While this anime isn't part of the beautiful fighting girl canon - though it has examples in two of the secondary characters - its influence on their subsequent development is profound. Not for aesthetic or thematic reasons, but for its introduction of a new medium of transmission of anime content for a niche audience - the OAV.

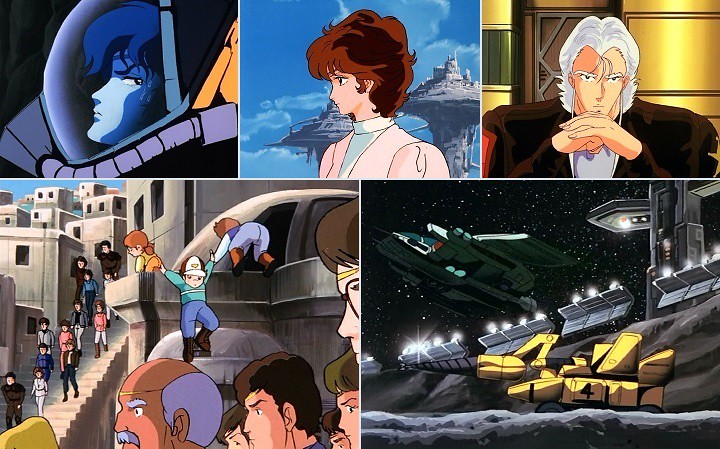

Dallos

Synopsis: When the dark side of the moon was found to be rich in minerals long depleted on an impoverished earth, colonisation rapidly followed. After 100 years of intensive, dangerous mining, the Lunarians still labour under the iron rule of their masters from Earth. Most have never even seen the blue marble, which isn't visible from their hemisphere. With miner discontent building, a group of third generation Lunarians agitate for outright rebellion, while older hands pin their faith on Dallos - a mysterious artefact (see image above) built long before any living person. Production details: Premiere: 16 December 1983 (part 2 was released first- apparently because the marketing team thought it was flashier; part 1 wasn't released until 28/01/1984) Director: Despite Mamoru Oshii (Gatchaman II, The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, Urusei Yatsura, Patlabor, Ghost in the Shell, The Sky Crawlers) being officially credited as director, significant portions were directed by his mentor, Hisayuki Toriumi (Gatchaman & Gatchaman II, Ultraman, The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, Space Warrior Baldios, Area 88, Lily C.A.T., Like the Clouds, Like the Wind) Studio: Pierrot Original story: Hisayuki Toriumi Screenplay: Mamoru Oshii & Hisayuki Toriumi Music: Hiroyuki Nanba & Ichiro Nitta Character Design: Toshiyasu Okada Art Director: Mitsuki Nakamura Mechanical design: Masahiro Sato Sound Director: Shigeharu Shiba Note: In the documentary included in the OAV, Oshii and other production staff give credit to Toriumi's contribution. Each directors' work on the production was largely independent of the other. Their efforts were then combined for the final releases. Apparently this working method had its tensions and, Oshii says, is reflected in the stylistic uneveness of the final releases. Toriumi directed part 1, Oshii part 2, thereafter the former concentrated on the dramatic scenes, while the latter the action scenes.

Director Mamoru Oshii is proud of his cyborg attack dogs. They are a highlight. Comments: In the accompanying documentary, Remembering Dallos, 1983 - 2003, Mamoru Oshii wonders if, "a project like this could be made now," and explains how, "back then, making a sci-fi or robot property without toys to sell wasn't possible." Oshii and Pierrot had been enjoying considerable success with Urusei Yatsura. The studio was also dabbling in the magical girl genre via Magical Angel Creamy Mami and had ambitions to muscle in on the giant robot genre. To that end they had been in discussions with toy manufacturer Bandai. Of the proposals put to Bandai, Dallos seemed the most promising, however after considerable development of the concept, as then chairman of Pierrot Yuji Nonukawa recalls, "We realised it wasn't suited to TV. They (Bandai) thought it wasn't the kind of show that would sell toys." Nonukawa had set aside a considerable budget for Dallos but, without the support of Bandai, a lengthy TV series was now out of the question. Industry acquaintences suggested that it be re-jigged into a shorter format and marketed to the emergent video hire market. And so it came to be that, accidentally, Dallos has the honour as the first ever OAV. In Anime: A History Jonathon Clements describes how the OAV disrupted anime in multiple ways. Firstly, it moved distribution from cinema complexes and TV networks to the local shop. Secondly, it enabled creators to explore new themes hitherto unavailable thanks to TV and cinema content restrictions and the ubiquitous marketing obligations. They could now produce anime geared for an older audience. Importantly, unrepeatable cinema and TV experiences could now be replaced by return visits to the video store or by fans buying the videos to create their own library. The OAV was the culmination of a trend towards an anime fan culture with its own self-aware history, a process begun with home VCR, fanzines and university anime clubs. In the wake of the OAV revolution the number of anime titles produced doubled between 1983 and 1986. (I recommend reading Justin Sevakis's article Why Were Anime Budgets So Big In The 80s? to get an idea of the Japanese ecomic bubble and its subsequent collapse.) In the aforementioned documentary, Oshii isn't the only one to miss the relative creative freedom provided by the OAV, which was, in turn, obliterated by the digital revolution. Even from their 2003 perspective anime had returned to the pre-OAV days of content restrictions and marketing limitations. In terms of the beautiful fighting girl survey it's a view I don't share - they will reach their apogee between 1995 (Oshii's own Ghost in the Shell) and 2007 (his protégé Kenji Kamiyama's Moribito - Guardian of the Spirit), although I may modify that stance as the survey progresses.

Top row (l-r): protagonist Sun Nonomura; love interest Rachel; and antagonist Alex Riger Bottom (l-r): the people gather in classic Eisenstein Odessa Steps fashion; Thunderbirds are Go! Getting back to Dallos itself, the combination of a heavily truncated narrative in the transition from extended TV series to four episode OAV, (along with the attendant change to an older audience), and the lack of directorial focus has left the viewer with a four episode series that is piecemeal, hamfisted, too often listless, and in some important narrative aspects, opaque or even contradictory. Between episodes two and three Dallos is destroyed and rebuilt, or so the Star Wars scroll tells us, but neither is depicted explicitly in the episodes themselves. Dallos (an artefact in the anime tradition of Ideon or Macross) was apparently built by humans though no one remembers why or how, yet there isn't any suggestion of an apocalyptic event that may have led to historical amnesia. It remains an annoying mystery and deus ex machina that will intervene inexplicably at the climax. Worse, for a self-avowed hard sci-fi story (as labelled in the documentary), the blue skies over the inhabited zones and the almost total disregard for the effects of lunar gravity, suggest either thoughtlessness or laziness. That said, thanks to the budget and Oshii' directorial skills, the action scenes aren't too bad. There are also moments where the imagery transcends the narrative. The unforgettable image, and the one that is reproduced wherever the anime is mentioned, is the protagonist's first glimpse of Earth - from a graveyard (see below). Whether Oshii or Toriumi was responsible is tantalising, but It's a precursor to Oshii's later characteristic penchant for extended, languid scenes that provide a sort of ironic commentary on the narrative. The visual quality of Discotek's release is pleasing, being both sharp and bright. The characters are neither well developed nor, with one possible exception, exceptional or memorable. To their credit, they are, at least, well articulated. The teenage protagonist, Shun, is yet another earnest, straightforward young man, who, like the viewer, doesn't really get what's going on, but he'll fight for the people who seem to have justice on their side. The composition of his grandfather's character tries to reconcile the irreconcilable by being simultaneously wise and close-minded. Revolutionary leader Dog McCoy isn't developed much beyond obsessed ideologue. In our times he'd be labelled a terrorist and his grievances dismissed. Shun's wannabe girlfriend, Rachel, is trite and conservative. In her favour, she does, eventually, take up arms for the cause. The most interesting character, in the context of 1983, is the composed and subtly effeminate antagonist, Alex Riger. The type - silver or blond haired, tall, with fashionable (for the 1980s) shoulder pads - will become clichéd and ridiculous in due course, but, at the time, was still relatively novel. I can think of the creepy Killi from Crusher Joe and the over-the-top camp antics of Leonardo Medici Bundle from GoShogun. Alex's more natural behaviour and his role in a serious sci-fi plot rather than a comedy, make him more believable than those two.

Pray that God grants you one final request May you rest, may you rest, may you rest, may you rest May you rest, may you rest in your grave new world Of interest to this viewer, is the OAV's internal Marxist dialogue - after all, the story is about labourers revolting against their absentee Earth-bound overlords. There is an ambiguity in that dialogue, as if the two writers (Oshii and Tomiura) didn't see eye to eye on the matter. In the documentary, Tomiura relates that the only thing in his head was Ashes and Diamonds, which may have been a dig at Oshii's worldview - the director of Ashes and Diamonds, Andrzej Wajda, was famous for his slyly ironic critiques of communist Poland under the Soviet Union yolk. If one takes Tomiura more literally then the Lunarians = the Poles and Earth = the Soviet Union. In the second episode, Oshii, as its sole director, is more overtly Marxist, and clearly inspired by Sergei Eisenstein, rather than Andrzej Wajda. Eisenstein said of Battleship Potemkin, "The film uses repetition from a tiny cellular organism of the battleship to the organism of the entire battleship, from a tiny cellular organism of the fleet to the organism of the entire fleet - thus flies through the theme the revolutionary feeling of brotherhood." This is mirrored in Dallos through the core of workers in the vanguard around Dog McCoy, to the miners en masse, to the residents of the workers' city of half a million people, who are analogues to the citizens of Odessa in Battleship Potemkin. The most striking parallel is the march of countless people down the city steps to meet the workers in solidarity - a scene that Oshii and Pierrot pull off with some aplomb. Sure enough, violence erupts, however the two sides are equally murderous, as if Oshii is more ambivalent than Eisenstein with his subject matter. Nevertheless, the film returns to its idealism when McCoy, in his final speech, reflects Eisenstein, "The pebble we cast has created ripples. Those ripples must have stirred their hearts." But, again, this is undermined by the famous final scene that is both bitterly ironic and profoundly pessimistic. Rating: so-so. A pre-eminent place in the history of anime, some memorable images and an interesting political subtext can't rescue a dull, uneven and, at times, opaque story. Unhappily there's almost two hours of dross before Dallos arrives at its best moment. Resources: Dallos and Remembering Dallos 1983 - 2003, Discotek Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle ANN (recommended reading, Justin Sevakis's Answerman article mentioned above) The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Top 100 Movies, John Kobal, Pavillion Books "New World", Grave New World, Dave Cousins, performed by The Strawbs, A&M Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Aug 15, 2020 8:39 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Oh dear! Thanks to a typo I've reviewed this slightly out of sequence. It should be here between Dallos and Oshin. I've moved the last two reviews each down a post and now inserted this review in its proper place.

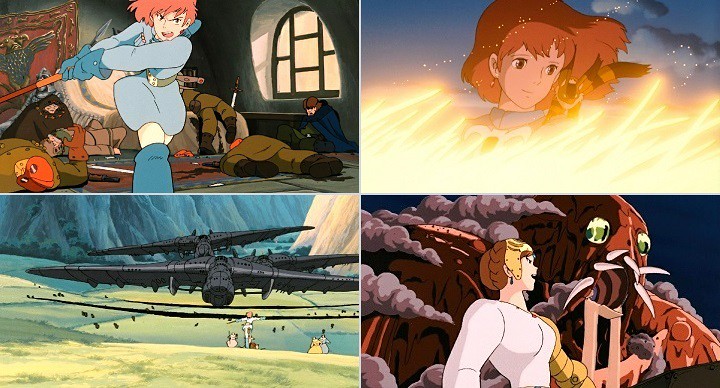

Beautiful Fighting Girl #39, Princess Nausicaä

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind Synopsis: A thousand years after the apocalyptic Seven Days of Fire human societies are slowly but surely succumbing to a jungle known as the Sea of Decay as it spreads its toxic spores and monstrous insect creatures across the planet. In a valley protected by prevailing winds and blessed with fertile soils and pure groundwater, young Princess Nausicaä searches for a cure for her father's terminal spore infection and, more generally, tries to understand the biological cycles of the jungle and the insects. When a giant airship belonging to the warlike Tolmekians crashes in the valley with an embryonic giant warrior from the Seven Days of Fire on board, Nausicaä and her people are unwillingly dragged into a battle for the future of humankind. Production details: Premiere: 06 March 1984 Studio: Topcraft Director: Hayao Miyazaki (reviewed in this thread - Lupin the Third (TV), Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro, My Neighbour Totoro, Porco Rosso, Princess Mononoke, Howl's Moving Castle and The Wind Rises) Source: Miyazaki's manga of the same name, published in Animage from February 1982 to March 1984. Screenplay: Hayao Miyazaki and Kazunori Itu Assistant Director: Kazuyoshi Katayama (Magical Fairy Persia, Maris the Chojo, Doomed Megalopolis, Those Who Hunt Elves, The Big O, Argento Soma, King of Thorn) and Takashi Tanazawa Music: Joe Hisaishi Character Design: Hayao Miyazaki and Kazuo Komatsubara Art Director: Mitsuki Nakamura Animation Director: Kazuo Komatsubara Notable future anime directors among the animation staff: Hideaki Anno (Evangelion), Mahiro Maeda (Gankutsuou: The Count of Monte Cristo) and Takashi Watanabe (Shakugan no Shana).

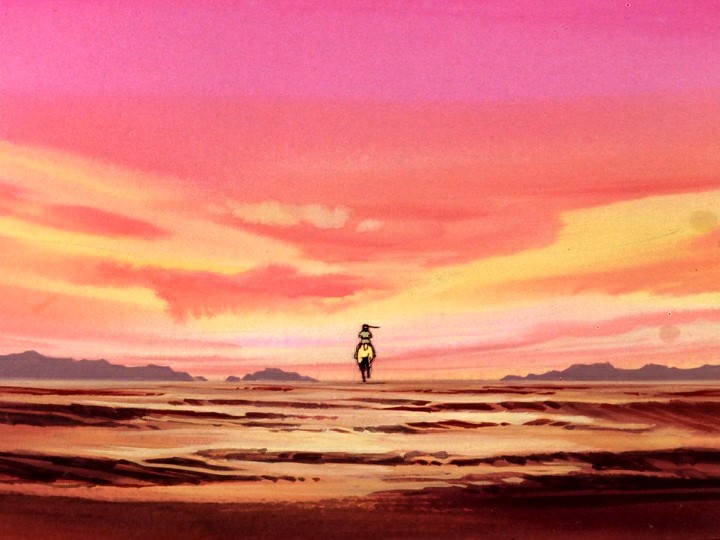

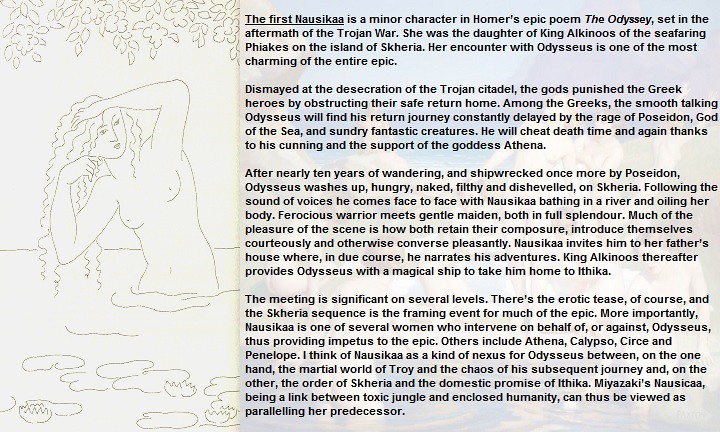

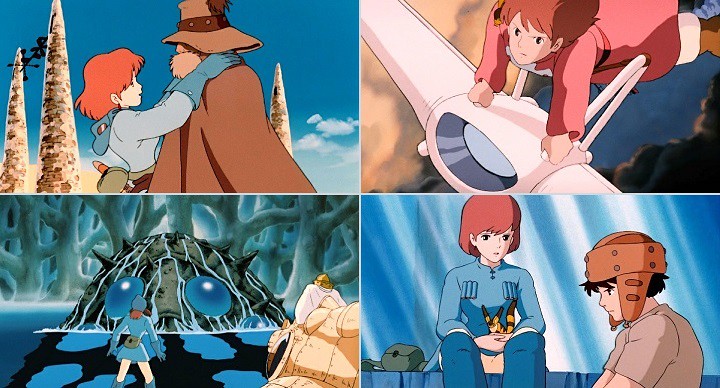

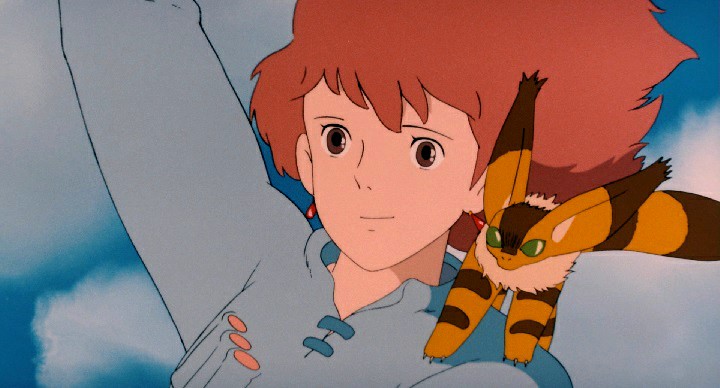

Nausikaa of The Odyssey; left image by Jackie Schuman; right background image William McGregor Paxton. Comments: Re-watching Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind in the context of this survey brings into stark relief how pivotal it is in the history of anime. There is anime before Nausicaä, and anime after. They are two different worlds. Here, at last, the possibilities latent in anime's beautiful fighting girl come into full blossom. For sure, the likes of Maetel (Galaxy Express 999) and Oscar (The Rose of Versailles) loom large as predecessors, but they are singular characters without obvious present-day counterparts. What's more, watching those two shows requires some tolerance due to their age and eccentricities, though the effort is worth it. Such forebearance isn't required with Nausicaä, thanks partly to the near-deification of Hayao Miyazaki ensuring that his visual stye retains its currency after nearly 35 years, but also because the eponymous heroine is so recognisably a female anime character. She has an appealing, sympathetic way about her that is childlike yet autonomous and vulnerable yet resolute, so familiar in today's female protagonists. The weird thing is that, while there's a multitude of like characters in her wake, I struggle to find an earlier exemplar among the 68 titles I've covered so far in this survery. The first to come to mind would be Miyazaki's own Clarisse from The Castle of Cagliostro, but she's anaemic by comparison. Probably the closest would be Simone Lorraine from The Star of the Seine who shares the combination of sweetness and (eventually in Simone's case) strength of character. Both Simone and Nausicaä are sites of sophisticated thematic discourse, although Miyazaki's is more overt and, in any case, thematic baggage attached to characters isn't uncommon in anime. In this film he seamlessly and succintly integrates his thematic obsessions with the narrative and the action sequences - more so than in his later films. Nausicaä plays multiple roles. As alluded to in the text box above she forms a bridge from the natural world to the human. She is scientist, explorer, warrior and leader. Above all, thanks to Miyazaki's wonderful construction and portrayal, she is a very human character, if singular in some ways. I want to look at some of her qualities and roles she plays within the context of the survey and examine how a male viewer like myself can find her so appealing and speculate how she allows me to step aside from my own gender and empathise with her. First is the sense of wonder that not only does she display as she explores the Sea of Decay, but it's a trope that hangs about her from the beginning as we witness her flying on her mehve to the end in her apotheosis among the ohmu. She's no goddess - well, untill the end, that is - as displayed by her rage as she kills the Tolmekian soldiers in her father's bedroom. I recall that the scene disturbed me the first time I viewed it, but not only does it fit one of the themes of the anime - death and rebirth - it also reveals her as flawed and thus human.

Top: death and redemption. Bottom: I love the gravity defying airships and the melting giant warrior. (That's Princess Kushana of Tolmekia in the foreground.) Hideaki Anno animated the giant warrior and, given the similarities to the aircraft in Daicon III I suspect he had a hand in them also. In her gendered roles Nausicaä proves herself a complex and paradoxical creation. She is sex object - witness her full bust, her constantly flapping skirt and skin-coloured tights. Seiyuu Sumi Shimamoto's appealing, childlike voice conforms to the anime ideal of juvenilised sexuality yet she is still able to meet the demands of a script that she be, in turn, commanding, terrified or outraged. Her American counterpart, Alison Lohman, gives a competent performance but sounds more adult and thereby less charming. Nausicaä is also daughter and child as demonstrated in her ambiguous relationship with Lord Yupa (more on that in a moment), in her behaviour with her father in the happy moments we witness prior to the Tolmekian invasion, and in the flashback scenes as she communes with the Ohmu. Indeed her whole relationship with the Ohmu is childlike in its deference. In addition she is a mother figure - to the people of the valley, in her nurturing behaviour and her compassion as displayed towards two juvenile ohmu. She is also potential lover to both the Pejite fighter pilot Asbel and the much older Yupa. Yet, importantly, she doesn't form any romantic bonds, confirming her autonomy while emphasising her solitude. A frequent trope of the film is the placement of the protagonist as a tiny figure in a vast landscape. That solitude demands our sympathy . The final paradox is that she is androgynous, despite her seeming sexuality, being both masculine and feminine in her behaviour. Susan Napier, in Anime from Akira to Howl's Moving Castle (but Akira came after Nausicaä!) describes the dichotomy thus, "She is a unique personality whose combination of "feminine" qualities (aesthetic delight, compassion, and nurturance) and "masculine" qualities (mechanincal and scientific ability and fighting prowess) create a memorable figure." Her androgyny isn't sexlessness, but rather, to use Napier's term, "omnicompetence". Male and female viewers are drawn to her. She is inclusive, and not a strange other. A favourite moment, among many, is when, on the pure sand beneath the Sea of Decay, Nausicaä smiles rapturously as she cries. She has discovered the final link in the chain of the polluted earth, the Sea of Decay, the Ohmu and the pure groundwater of the Valley of the Wind. My emotional response is precisely in tune with hers. She has become my hero. Tamaki Saito considers the film of supreme importance in his study and I'd like to quote him at length.

This brings us back to the Nausikaa of Greek legend who mediates between the fantastic and the domestic. She is an apt inspiration for an epic tale set in a dystopian future.

Nausicaä and (clockwise from top left) Lord Yupa, her mehve, Asbel and an Ohmu. The film has three other memorable characters. In the Disney dub Patrick Stewart plays Lord Yupa as... well, Patrick Stewart, and that's good enough to win me over. The Japanese dub's Goro Naya, with his gravelly voice, is gruffer and sterner, but every bit as successful. The Tolmekian warrior princess Kushana is an ambiguous villain who sets the mould for Mononoke's Lady Eboshi (though not as good). Like the viewer, she is captivated by Nausicaä, even forestalling action just to observe what her nemesis might do. Kushana also gets the best line in the movie, when she removes her prosthetic arm gained following an insect attack, "Whatever lucky man becomes my husband will see worse than that." She is Nausicaä's antithesis: creating division, rather than connection. Nevertheless, she engenders sympathy for her ill fortune, her self-deprecating manner, her sneaking admiration for the protagonist, and because she's misguided rather than bad. Her fawning, cynical and indolent offsider Kurotowa provides comic relief that, miracle of miracles, doesn't spoil the narrative. Chris Sarandon's oily enunciation gives him the edge over his more straightforward Japanese counterpart. I must also mention two other characters: in Teto the fox squirrel, with its constant activity and affection, this survey finally has a captivating mascot character; Pejite fighter pilot and potential love-interest Asbel is a template for Mononoke's Prince Ashitaka - and even duller. Other criticisms are but nitpicks. For the most part the film is gorgeous to look at - this is a Miyazaki film, after all - but it was made on a budget and, occasionally, clumsy effects draw attention to themselves, such as double exposures or cutout animation. They can be forgiven as Miyazaki's means don't always match his ambition. More annoying is his persistence with unnecessary dialogue. Too often characters describe exactly what the viewer is seeing. Nausicaä's running description as she explores the Sea of Decay is both superfluous and distracting. In the illuminating commentary track Hideaki Anno and Kazuyoshi Katayama put it down to the film's origins as a manga. Likewise the sometimes corny action antics are also attributed to its manga influence. And, the messianic levels to which Nausicaä ascends in the climax might just be a step to far for some tastes. Admittedly, her sanctification makes sense thematically.

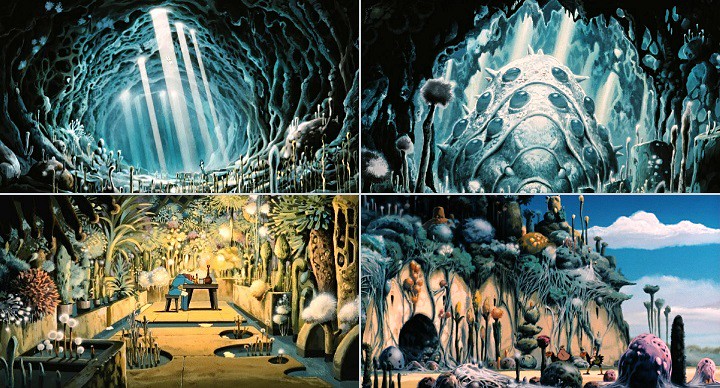

The world of the Toxic Jungle, aka the Sea of Decay, aka the Sea of Corruption. That's Nausicaä's laboratory bottom left. The film marks the first collaboration between Miyazaki and Joe Hisaishi, who utilises Hammond organ, synth and drum machines to provide an effective range of sounds from techno to prog to orchestral. Despite the blatant rip-offs of Terry Riley, Tangerine Dream and even Frederick Handel, Hisaishi embellishes the wonder, mystery and terror of the film. He would later recycle elements into his soundtrack for Robot Carnival. As Miyazaki's budgets grew, Hisaishi would have full orchestras at his disposal. Rating: masterpiece. A near perfect blend of action, narrative and thematic material, a magisterial visual experience and, above all, a singular, charismatic and empathy-earning protagonist mark Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind as one of the pinnacles of the project to date, along with The Rose of Versailles. It remains, with Porco Rosso, my favourite Miyazaki film, retaining all the wonder of the first viewing yet improving as I understand it better. Resources Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Madman Bluray ANN The Odyssey, Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald, Vintage A Handbook of Greek Mythology, H J Rose, Penguin Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press Anime from Akira to Howl's Moving Castle, Susan Napier, St Martin's Griffin The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Anime Explosion: The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation, Patrick Drazen, Stone Bridge Press

Last edited by Errinundra on Tue Feb 15, 2022 4:22 am; edited 6 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl #40: Shin Tanokura

Oshin Synopsis: Living in the early years of the 20th century, Oshin is the young daughter of an impoverished rice farmer. Their dire circumstances lead to her being indentured as a baby-sitter to a timber merchant downriver from their farm. She endures constant abuse from the parents, the head maid and even the pet cat. When she is falsely accused of theft, Oshin escapes into a blizzard where she is saved from freezing by a huntsman, a deserter from the Japanese army after fighting in Korea. Making her way back home (and a severe beating from her father for breaching her contract with the timber merchant) Oshin is indentured again as a baby-sitter to another family. Things turn out more favourably this time after she saves the older daughter from a falling telegraph pole. Production details: Premiere: 17 March 1984 Studio: Sanrio (of Hello Kitty fame) Director: Eiichi Yamamoto (encountered frequently in this thread, including Tales of the Street Corner, Kimba the White Lion, A Thousand and One Nights, Belladonna of Sadness, Cleopatra, Space Battleship Yamato (series composition) and Urotsukidōji: Legend of the Overfiend (supervision)) Source material: the live TV series Oshin broadcast from 4 April 1983 to 31 March 1984, written by Sugako Hashida and modelled partly on the mother of Kazuo Wada, who founded a chain of supermarkets, and on anonymous letters sent to a women's magazine. Storyboard: Satoshi Dezaki (brother of Osamu Dezaki and director of numerous anime, including the first half of Star of the Seine and A Time Slip of 10000 Years: Prime Rose) Masaharu Endo and Susumu Kagaya Music: Koichi Sakata Character Design: Akio Sugino (Ashita no Joe, Aim for the Ace!, The Star of the Seine, Nobody's Boy Remi, The Rose of Versailles, Space Adventure Cobra, Golgo 13, The Legend of the Galactic Heroes and Black Jack, among others)

Girl and landscape. Comments: One of Japan's most beloved and successful TV shows, the live version of Oshin garnered an average audience share of 52.6% for its morning timeslot, with a peak of 62.9%. The series was subsequently aired in 68 countries, being especially popular across Asia and the Middle East. The animated film, for its part, covers the early episodes - the childhood years - of the TV series, re-using the scripts and the voice of the child actor, Ayako Kobayashi, in the title role. Oshin valorises the characteristic Japanese virtues of perserverance, hard work and respect, although those qualities don't earn her much in the way of good fortune until the closing scenes. She endures beatings from her father and others, is sold off as a domestic worker, and suffers from the cruelty and injustice from her employers. As one of the key elements that frames the narrative and themes of the film, the character of Oshin carries much of the load on which the success of the film depends. The problem is that those virtues mentioned above leave her, for the most part, as a passive character. Things happen to her; she isn't the catalyst of the events of the film. She could be considered as an early example of moe, where her misfortune and her inferior status engender a protective sympathy in the viewer, and where her rare smiles act as little rays of sunshine on the prevailing chill. Viewers at the time would have already developed a strong attachment to Oshin, thanks to the TV series, so Yamamoto didn't have the need to emphasise her positive nature. That leaves him at risk of her coming across as dull for other viewers. Given that her birth year is 1900, Oshin is also intended as a feminine representation of 20th Century Japanese history. Her passivity and perserverance - yamato nadeshiko, if you will - signify the country's image of itself. (In anime the Japanese male viewers' capacity to empathise with, or relate to, female protagonists may be rooted in this feminised view of self.) A problem, to this Australian viewer, is that, while the representaton of Japan by these idealised traits may have been applicable to the average Japanese person ruled by a junta in the first half of the century and then by the whims of capitalism in the second half, it ignores the very active role played by the nation on the world stage. That's a common critique of Japan, so I'll leave it at that. What I will say is that, despite the austerity and the occasional violence, the film isn't as grim as you might imagine. Perserverance, after all, has a sense of hope at its core.

Oshin is surrounded by people, both helpful and threatening. Note the head tilt (top right) - twenty years before Akiyuki Shinbo. Oshin's arrival home (bottom left) brings to mind The Tree of Wooden Clogs and earlier Italian neo-realists. The anime film may have ridden on the coat-tails of the phenomenal successs of the TV series, but it does shine on its own in one highly memorable way - the artwork. This is a film besotted by landscapes, the seasons (particularly winter), the elements, and, to a lesser degree, the textures and architecture of rustic, domestic life. Director Eiichi had already showcased his unique, painter's eye in Belladonna of Sadness. Not as radical as in that film, Yamamoto again demonstrates his gift for frame composition and his fearless penchant for empty space. The power of empty space is that it brings into stark prominence the other elements of the frame. Analogous to this is his use of the human figure - most often Oshin - against a vast, natural landscape. Almost always the character is left of centre in the frame and gazing to the right, to lead the viewer's eye to the scenery. It simultaneously places the character, and the viewer, in the scenery, but also at odds with it. The natural world is mute, indifferent, even hostile, but wondrously beautiful nevertheless. Some two years earlier Isao Takahata attempted something similar with Gauche the Cellist, although, in that instance, the placement of the diminutive individual in the landscape is to locate them in Kenji Miyazawa's numinous universe. Yamamoto's vision is more severe, more austere and more threatening. Coincidentally, Takahata's later Only Yesterday shares Oshin's Yamagata setting, albeit presented benignly. (My emphasis on the appearance of the film may be a result of watching it raw.) Yamamoto was house director for Mushi Productions and long time collaborator with Osamu Tezuka. For sure Tezuka gave Yamamoto opportunities he may not have had elsewhere, but I think that he inhibited Yamamoto's great gift - his visual skills. There's a considered elegance and seriousness to Yamamoto's work that enhanced Tezuka's vision, providing it with a gravitas all too often in short supply. In return Tezuka leavened Yamamoto's contributions with his signature goofy humour. That's missing in Oshin where Yamamoto follows the early Toei and Mushi habit of using animals for comic relief. There's a mouse family in the roof of Oshin's family home whose good will and humour is meant to provide a counterpoint to the discord below, but only manage to trivialise the tone of the film. Somewhat more successfully, the cat mentioned in the synopsis is a caricature of the cruelty Oshin suffers at the hands of the merchant family. In its turn it will be at the receiving end of an unexpectedly vicious comeuppance.

She does smile. Once or twice. Rating: good. The abiding impression of Oshin is a film of austere beauty and domestic cruelty that valorises and romanticises the qualities inherent to the titular character - perserverance, hardwork and respect. The humour, infrequent as it is, has a tendency to undermine the tone, and, while Oshin is presented sympathetically, she is somehat dull. Despite these shortcomings, and the lack of subtitles, the sheer beauty of the images made this worthwhile. Resources: ANN The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Last edited by Errinundra on Tue Feb 15, 2022 4:22 am; edited 6 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl #41: Jeanne Francaix

Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross Synopsis: Mecha pilot and girl about town Jeanne Francaix unexpectedly finds herself replacing her squad commander just as her planet, Gloire, is attacked by alien invaders - the human-like Zor. The superior technology of the aliens will test the skill and bravery of Jeanne and her fellow soldiers, however the Zor's hesitation in launching a massed attack upon the humans suggests that they have problems of their own. When Jeanne and her team infiltrate an enemy battleship they encounter a peculiar society whose social structure is on the point of collapse. And discovering who or what is piloting their opposing mecha will be thoroughly unnerving. If Jeanne and her team can figure why the Zor are so desperate to conquer Gloire they may be able to avert their looming annihilation. Production details: Premiere: 15 April 1984 Studio: Big West and Tatsunoko Production Director: Yasuo Hasegawa Source: original material Series composition: Jinzo Toriumi Music: Ken Sato and Yuji Dan Character design: Tomonori Kogawa, Miyo Sonoda and Hiroyuki Kitazume Mechanical design: Ammonite, Hiroshi Ogawa, Hirotoshi Okura and Takashi Ono Animation Director: Yutaka Arai

Jeanne Francaix moods. Comments: It's funny how things come up under the radar. Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross turned out to be a pleasant surprise - proving itself quite a groundbreaking TV series. In the 17½ years or so between its premiere and Sally the Witch in 1966, this is just the third series with a female protagonist aimed primarily at a male audience. Of the other two Queen Millennia hedged its bets by having a boy, Hajime Amamori, as the point of view character. I've been assiduous in tracking down shounen and seinen TV series with female protagonists and, as far as I've found, this is the first since Cutie Honey in 1973, and the first since Space Battleship Yamato (1974) ushered in the otaku era, where the story is told from a female perspective. Unlike the raunchy magical girl show, SDCSC presents its female characters positively. And, of course, SBY's cheesecake Yuki Mori is hardly a protagonist. In terms of character type and personality Jeanne isn't as innovative as her ground-breaking role in anime history might otherwise promise. She's hot-headed - an important thematic element once the Zor society is encountered - spends her wages on clothes and nightclubbing, and has little respect for authority or pretension. Given that her provenance is within the Super Dimension Fortress Macross production environment (though the narrative setting is unique), I'm not surprised by her tilt towards clownishness, something she shares with her confederates. Jeanne could fit easily into the bridge crew of the Macross spacehip. Her lineage can be traced from Françoise Arnoul (Cyborg 009) through Michiru Saotome (Getter Robo), very directly with Remy Shimada (as per the original GoShogun) and Misa Hayase (Macross). Like each of those, she's supremely competent at her job. Once clad in her armour suit Jeanne is peerless as a fighter and proves herself a capable commander of the 15th squad. Of course, where she tops her predecessors is that this is her show where the male characters defer to her. That all said, I get the impression that Tatsunoko were attempting to garner female viewers, given her feminine gendered behaviours (which may have been intended also to satisfy male audience expectations) and floral themed resolution to the conflict. If so, the show's low ratings and cancelled episodes suggest the move backfired.

Musica and Bowie. As in Super Dimension Fortress Macross, music and romantic love trump militarism. Jeanne isn't the only pioneering character. Subordinate mecha pilot Bowie Emerson is even more interesting. African characters have been used in anime occasionally prior to SDCSC, and positively at that - think of Pyunma from Cyborg 009 - but the design team have avoided reducing his appearance to caricature, as so often happens in anime - think Pyunma again. Bowie's role and pigmentation are central to the major theme of the series - that love and peaceful co-existence do not exclude difference. His heroic behaviour and his love affair with the alien Musica accelerates the Zor's crisis and is the exemplar for the options open to them. To give one character dark skin might smack of tokenism, but the quality of his depiction (among other things he's a gifted musician) eliminates that problem. It helps that he is the least clownish member of the squadron and that the point of view character, Jeanne, holds him in high regard. Caution, though: please don't get the impression that this is a masterly character piece. Jeanne and Bowie are more notable for breaking new ground than for their penetrating portrayal. Other mildly interesting characters - male and female - grace the show. Bowie's estranged father General Rolf Emerson (who looks Eurasion - I suppose it's possible) is torn between resentment at his son's rejection and his parental fear at sending him into battle. The general must also repress his preference for a properly considered strategy in the face of his own superior's belligerance. Jeanne's love interest, the weirdly pink-haired Seifriet Weiss, is abucted by the Zor and, shall we say, tampered with. On his return this leaves his comrades in some doubt as to his trustworthiness. The show's narrative limitations meant that I knew there was only one place his subplot could end up at. Cool explosions, though. Jeanne also has two rival female officers whose strong characterisations enhance the show. One is the commander of another mecha squadron, Marie Angel, who's both the best fighter pilot out there and disdainful of Jeanne's merits. Her prim military outlook crumbles under the seemingly genuine persistence of the biggest philanderer on the base, Charles De L'Étoile. The other is Lana Isavia, an ambitious officer in the Gloire Military Police. She's sure Jeanne is up to no good (and she's often right), but has a road to Damascus moment as the series approaches its climax.

Top row from left: Lana Isavia; Seifriet Weiss and Marie Angel. Bottom: 15th squad members Andrzej Sławski and Louis Ducasse with his Velvet Underground sunglasses; the Zor leaders in typical trinity form. The Zor aren't depicted nearly as well. Entering their domain is tonally akin to leaping from an episode of Super Dimension Fortress Macross into Space Runaway Ideon. Imagine gigantic space battleships inhabited by whole societies of Vulcans from Star Trek. As with Spock's kind, the Zor have renounced emotion. To achieve this they have engineered their biology so that everybody is born as triplets where each member specialises in either information gathering, decision making or taking action. This arrangement has enabled them to advance technologically, but proves itself unstable under pressure. A trinity that loses a member becomes dysfunctional. How such members are dealt with is another disturbing secret for Jeanne and her comrades to unravel. No surprises, then, that passionate personalities like Jeanne or Bowie are such a threat to them. For sure, this is a cool science fiction concept, but, while I must give the show its props, there's a major hurdle that it never quite clears: the sheer dullness of the Zor as personalities, including even the sweet Musica. Worse, the show's dalliance with these concepts and the way in which the script handles their development and integration into the narrative means that the otherwise appealing human characters become mechanical players in the unfolding philosophical speculation. In other words I became less engaged by them. That the series was cut short, causing the creative staff to truncate things, probably contributed significantly. Whatever the cause the series isn't able to engender in this viewer the level of anxiety or engagement or even amusement I've experienced with some other mecha shows I've recently covered. SDCSC has a number of musical motifs in its narrative. Both Bowie Emerson (David Bowie meets Keith Emerson - geddit?) and Musica are gifted musicians, to provide an obvious example. You could say that together they represent harmony amongst the dissonance of the war between human and Zor. Musica's melodies are elegant but sterile; Bowie's have a jazz inflected yearning. You could say that their effect is a muted version of the chaos created by the combination of sexiness and melody that Minmay unleashes upon the Zentradi in Super Dimension Fortress Macross. I like the argument: that the intimate events in life far outweigh war in importance and must eventually prevail. Easy enough to say in times of peace. While on the subject of music, the soundtrack may be a dated fusion of prog and glam rock - around this time anime soundtracks often sound about a decade behind western popular music - but, whoever the lead guitarist is, they've certainly mastered their prog rock licks. Great stuff. Rating: decent. On the plus side Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross gives us two ground-breaking anime TV characters and a nifty sci-fi concept to grapple with. On the minus side the alien invaders are too dull to engage or amuse, and the ending, while making sense, is rushed. Resources: ANN The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Recommended reading: Justin Sevakis's Buried Treasure article Last edited by Errinundra on Tue Feb 15, 2022 4:23 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl #42: Persia Hayami

Magical Fairy Persia Synopsis: For her first eleven years Persia led a carefree life running with lions on the plains of East Africa. She is uprooted from this wild but idyllic life when a kindly old man decides she would benefit from the cultural milieu of suburban Tokyo in the care of adoptive parents. A strange encounter on her flight to Japan leaves Persia with a magical hairband that transforms her into a teenage girl named Fairy, three tiny kappa companions and a mission to collect love energy from the human world in order to unfreeze the dreams of the fairy world. As if that mission isn't hard enough, Persia soon discovers that urban life presents its own challenges to a girl from the wilderness. Production details: Premiere: 06 July 1984 Director: Takashi Anno and Kazuyoshi Katayama (assistant director: Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: director: Maris the Chojo, Doomed Megalopolis, Those Who Hunt Elves, The Big O, Argento Soma, King of Thorn) Studio: Pierrot Source material: Persia ga Suki! by Takako Aonuma, published in Weekly Margaret from January 1984 to November 1985 Music: Koji Makaino (The Rose of Versailles, Magical Angel Creamy Mami, Leda - the Fantastic Adentures of Yohko, Magical Idol Pastel Yumi, Bubblegum Crisis) Character design: Akemi Takada (Urusei Yatsura - hence the leopard skin outfiit, Magical Angel Creamy Mami, Maison Ikokku, Kimagure Orange Road, Patlabor, Licca-chan, Fancy Lala) and Yoshiyuki Kishi Art director: Mitsuki Nakamura and Satoshi Miura

Clockwise from top left: Persia saves the day once more - this time on a building construction site; The transformation sequence, and much else, is inspired by Fairy Princess Minky Momo; Persia's alter ego is normally rather more demure; and Persia's magical companions - the cat is a transformed wild lion from Africa. Comments: This is the sixteenth magical girl show I've featured in this survey. Only three are fully viewable with English subtitles - Princess Knight, Cutie Honey and Magical Angel Creamy Mami - and all three exist thanks to being licensed. This demonstrates again one of my theses: that our Anglophone perception of which titles are significant in the history of anime is distorted by those overlooked genres popular in Japan and elsewhere. (It also indicates the preferences of fansubbers.) I managed to watch eight episodes with English fansubs and, suprisingly, only seventeen raw. Thanks to the dependability of finding European dubs of magical girl shows on YouTube I managed to watch the rest of the series via the French version, Vanessa et la Magie des Rêves. Magical Fairy Persia forgoes most of the innovations of Studio Pierrot's first foray into the magical girl genre, Creamy Mami, instead relying more on Studio Ashi's Fairy Princess Minky Momo for its template. They share an exotic provenance, their transformation choreography, the variable and occupational themed nature of the transformed young woman whose usually brief appearance resolves the episodic crises, a similar overarching goal - accumulate love points v hope points to restore dreams, and a retinue of mascot characters. MFP reduces the role of the transformed girl and re-establishes a Toei-like emphasis on the day to day life of a Japanese schoolgirl, albeit one who is something of a fish out of water. Much of the fun in the early episodes revolves around Persia's cluelessness when it comes to acceptable behaviour. MFP altogether lacks Minky Momo's morbid diversion and largely avoids the identity conflict between the original and transformed selves that provides much of the tension, and pleasure, in Creamy Mami. Such an identity conflict is explored briefly when Persia briefly loses her magical ability, again in an arc where the transformed girl (but not, it seems, the original) falls in love with a musician, and at the end when we discover the truth behind Persia's alter ego, Fairy.

Clockwise from top left: Persia's adoptive parents are basically a reprise of Creamy Mami's; From the top, irascible Sayo, her boyfriend Riki, his twin Gaku, and Persia taking care to preserve her modesty; My favourite character after Persia - the scheming, clever, lovelorn Yoyoko; Twin brothers - despite appearances - Riki and Gaku; and This female tag-team wrestling duo Oscar and André fight as the Lovely Pair - that's two shout-outs in one. The best thing about the show is Persia herself. Her magnificent electric blue, lion's mane hair ensures she is the focus of every frame in which she appears. She is a marvellous design. That, combined with her more clownish behaviour when compared with most of her predecessors, made this a relatively easy watch in the episodes without subtitles. Her transformed version, with her beetroot coloured hair, is prosaic by comparison - not helped by her more earnest persona. Just as well the latter's appearances are brief. A noteworthy aspect of the show is how Persia subtly develops over the 48 episodes. Initially she is clownish and often the victim of events. Over time she becomes more thoughtful and observant. To match this, her facial appearance becomes more mature. Ever the action girl she is forever intervening in the affairs around her - mostly comically in the first half, but more effectively later. Despite her assigned mission she spends few episodes pursuing love energy and, thus thankfully, the series isn't cursed with the cloying sentimentality such a goal might entail. That's not to say that romantic love isn't a constant thread running through the show. There's Fairy and the musician as already mentioned, Persia and Gaku - one of the twin grandsons of the old man who brought Persia to Japan, the other grandson Riki and his irascible - well, tsundere - girlfriend Sayo, and Persia's rival schoolgirl Yoyoko's crush on Gaku. Portrayed with humorous affection for the most part, the relationships are fun without becoming tiresome. The most important characters after Persia are the twin boys, Gaku and Riki. Their unforced, unstinting loyalty toward and affection for the protagonist, combined the overall humorous tone of the show, makes them highly appealing. Gaku is the chief love interest for Persia. Their long association and easy comfort around each other means the show completely and refreshingly avoids the awkward embarrassments that infect so much other anime. They fit together so well neither fully appreciates how important the other is until, near the end, it is revealed that the grandfather is returning to Africa and taking the boys with him. The shipper in me approved that development. I mean, Persia is only eleven years old. Better Gaku goes away for ten years before they hook up. Twin brother Riki isn't about to cause any rivalry issues thanks to his pre-occupation with his demanding girlfriend, Sayo. She's an early example of a tsundere character, following closely on the heels of the archetype, Pierrot stablemate Lum from Urusei Yatsura. So, yes, she clobbers Riki whenever he frustrates or annoys her. In typical anime fashion he accepts the domestic violence with forbearance. She calms down in later episodes, becoming a reliable part of Persia's expanding social world. There are some odd elements. As with Creamy Mami, Persia has been cautioned that, should her magical powers be disclosed or discovered, she will lose them altogether and, even worse, Gaku and Riki will be turned into girls. What on earth is the underlying message here? That being a girl is a form of punishment? If so, why should other people bear the brunt of the reprisals for Persia's indiscretions? That is one messed up, albeit peculiarly amusing, value system. And, before I move on to the show's connection with Satoshi Kon I must mention the retrograde background artwork compared with Creamy Mami. Gone are the angular lines and abstract watercolour images. We are back to the plain, functional look of earlier magical girl shows. Sure, Shinichiro Kobayashi's style (see also Revolutionary Girl Utena and Simoun) takes some getting used to, but his work is an essential part of Creamy Mami's appeal.

Points of connection between Persia and Paprika. Magical Fairy Persia and Paprika: In episode two, Persia, newly arrived in Japan, decides that she needs to be re-united with her most precious companion from Africa, the lion king Simba. Seeing the very same Simba in a live broadcast, she uses her newly acquired magic to leap into the television screen and emerge from the camera lens, whereupon she abducts Simba and returns to Japan. Immediately I wondered if Satoshi Kon's deployment of the very same gimmick in Paprika was coincidence, rip-off, tribute or part of his postmodern, intertextual gameplaying so characteristic of both Paprika and Millennium Actress. Kon's Paprika is an adaptation of Yasutaka Tsutsui's novel, which, in itself, doesn't reference MFP. Rather, what we have is Kon adding an extra, referential layer for the film. And, although it isn't normally described as such, Paprika is a magical girl film, albeit without any elaborate transformation sequence. The trope is reversed. We get a thirty-something-year-old woman instead of an eleven-year-old girl transforming into a seventeen-year-old. Persia's catchcry to begin her transformation sequence is "Papurikko!" ( example 1, example 2) thereby providing, for Kon, the obvious point of connection to the novel. In the best episode of the series (20 - Magic Cannot be Used) Persia faces an existential crisis when her kappa companions vanish and her magic forsakes her after she has transformed. Part of Persia's terror comes from her discovery that mirrors display her real self, not the transformed girl she has become. The trope of a different self on the other side of the mirror is characteristic of Kon. The final link can be found in the soundtrack. This short sequence frequently heard in the TV series is taken by composer Susumu Hirasawa and transformed into Meditational Field and The Girl in Byakkoya, two pieces central to Paprika. (The loudest voice heard in the sound bite belongs to Yoyoko. Persia can be heard right at the end.) The discovery of these links, arcane as they are, sheds light on two moments in the film where characters declare the need for "papurikka": Tokita in the guise of the yellow robot and Paprika herself before the gigantic, evil, transformed Seijiro Inui. If "papurikka" is the signal for the magical girl to appear, then we have the geek expressing his desire for her and, even more importantly, the necessity of her intervention to resolve the biggest plot hole ever created. Paprika, is among other things, a satire on anime narrative conventions and magical girl tropes are ripe for the picking. Anyway, after this I'm not about to complain about Christopher Nolan or Darren Aronofsky. Rating: So-so. Magical Fairy Persia is a step down from Pierrot's previous magical show, Magical Angel Creamy Mami. The story telling is less compelling and the artwork - Persia aside - is less striking. The magical elements are, much of the time, downplayed, so that the narrative impulse comes from other events in the protagonist's life. In othe words, the series rarely explores the implications of being a magical girl, thereby returning to the mundanities of the earlier Toei shows of the genre. The show's best element is Persia herself, but for all her appeal she isn't compelling enough to lift the show above mediocrity. Resources: ANN The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Paprika, Sony

Last edited by Errinundra on Tue Feb 15, 2022 4:23 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

Alan45

Village Elder Village ElderPosts: 10022 Location: Virginia |

|

||

|

@Errinundra

While scrolling down to your current entry, my eye was struck by your previous entry on Jeanne Francaix. Something seemed familiar though I have not watched that show. It finally hit me. She was the subject of the fourth Robotech doll. Matchbook toys put out a set of four Barbie sized dolls based on the Robotech franchise. The first three are the love triangle from the Macross series. My wife picked up the whole set and associated clothing packs on clearance at a random toy store on a trip. I think she wanted Rick Hunter as a boyfriend for Barbie but we bought the whole set as it was dirt cheap. Other than the obvious cartoons on the boxes we had no idea the background of the dolls. By the time we got the dolls (mid 1990s) Robotech was long gone if it had ever been screened locally. We didn't find out until I got into anime several years later. I eventually bought the AnimEigo version of Macross and it became clear where the first three dolls came from, but nothing on the blond. Identification was made difficult because she was sold in a pink and white striped party dress and Matchbox did a really bad job with the hair (it looks like a blond afro). Also the name was given as Dana Sterling. Her flight uniform was available as a clothing pack though. So, thanks, now I know where the lonely fourth doll comes from and her real name. Jeanne Francaix, is European enough, I wonder why they thought they had to change that one?? |

|||

|

|||

|

Beltane70

Posts: 3971 |

|

||

Her name was changed in Robotech to make her the daughter of Max and Miriya Sterling from the Macross Saga part of the series. |

|||

|

|||

Alan45

Village Elder Village ElderPosts: 10022 Location: Virginia |

|

||

|

@Beltane70

Thanks, I do have the Robotech version of the Macross Saga from ADV but I never got around to watching it, sometime maybe. |

|||

|

|||

|

Beltane70

Posts: 3971 |

|

||

|

Out of the three separate shows that made up Robotech, Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross underwent the most changes.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

You're most welcome. Any chance of posting a pic? |

|||

|

|||

Alan45

Village Elder Village ElderPosts: 10022 Location: Virginia |

|

||

|

I'm currently with out a photo hosting service (since Photobucket got snarky) If you PM me an e-mail address I'll send you photos of the whole set you can post.

|

|||

|

|||

|

All times are GMT - 5 Hours |

||

|

|

Powered by phpBB © 2001, 2005 phpBB Group