Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Zin5ki

Posts: 6680 Location: London, UK |

|

|||

The slice-of-life elements never quite dovetailed with the film's sobering core, I found. The early scenes wherein Suzu relocates and marries are not tedious or unnecessary, though to a certain extent they were disjointed. One can tell the source material was of a serial format rather than being a single volume narrative. Of course, by the time the film finally becomes focused and coherent, the characters are in as dire a situation as one could imagine. Anyone would be forgiven for preferring the clumsy but careless first act to the horrific weight that the story ultimately carries. |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girls index

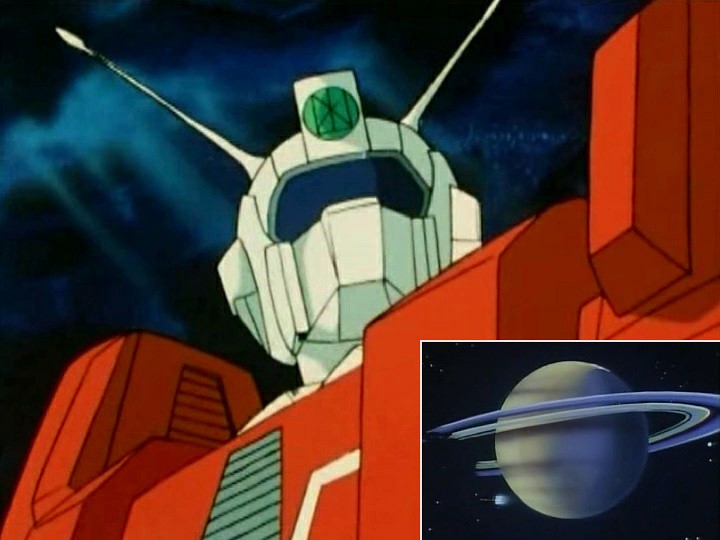

**** Splash(es) of Crimson #8: Maria Grace Fleed & Hikaru Makiba

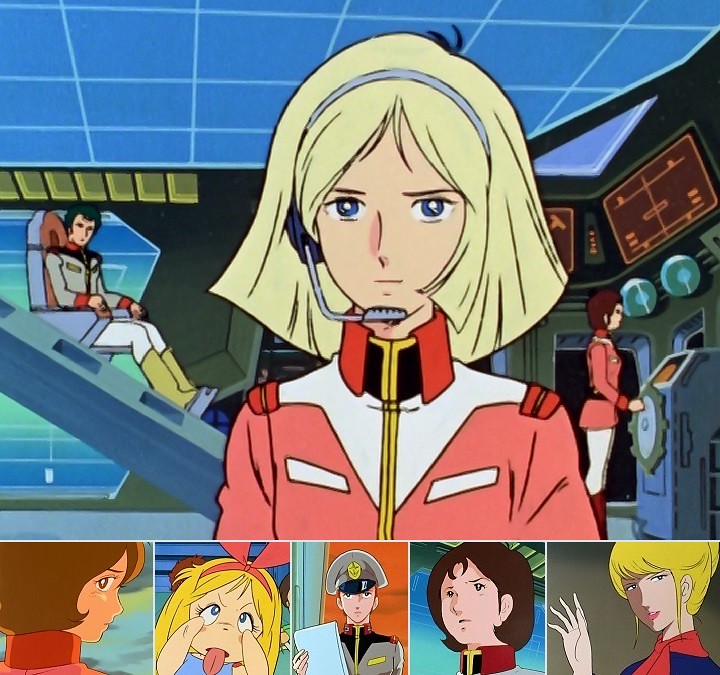

UFO Robo Grendizer Synopsis: Vegans are rampaging across the galaxy, spreading their evil social justice values thanks to the overwhelming superiority of their vegatronic energy. The planets they don't enslave, they reduce to unpalatable wastelands. Duke Fleed is a young refugee from one such devastated world, fleeing to earth with his powerful giant robot come spaceship, Grendizer. Once on earth he becomes the adopted son of Doctor Genzo Umon, who researches cosmic energy sources at his Space Science Laboratory outside of Tokyo. When Duke Fleed (aka Daisuke Umon) isn't fighting Vegans, he works on a neighbouring ranch run by Danbei Makiba, his daughter Hikaru and young son Goro. The Vegans, with the vegatronic energy almost exhausted and their home planet in terminal decay, launch an invasion of earth from the dark side of the moon, but they must first neutralise Grendizer. Duke Fleed is soon joined by Koji Kabuto - former pilot of Mazinger Z - fighting in his home-built flying saucer, while Doctor Umon designs and builds rocket powered fighter craft for their battles. In due course Hikaru is recruited to fly one of the "spazers" and, when Duke Fleed is re-united with his hitherto presumed dead sister Maria Grace, the team is complete. The four will fight the Vegans to the bitter end. Production details: Premiere: 05 October 1975 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #18 The Star of the Seine and Beautiful Fighting Girl #19 The Wild Swans Studio: Toei, Dynamic Planning Chief director: Tomoharu Katsumata (see Mazinger Z) Source material: original production although manga adaptations ran simultaneously as Yufo Robo Gurendaiza in various magazines. Creator: Go Nagai Script: Go Nagai Music: Shunsuke Kikuchi Character Design: Kazuo Komatsubara, eps 1-48, & Shingo Araki (Cutie Honey, Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid, Galaxy Express 999, Lunlun the Flower Child, The Rose of Versailles, Mahou Shoujo Lalabel, Legend of the Galactic Heroes), eps 49-74 Comments: Go Nagai further refines and develops the giant robot formula he began with Mazinger Z and continued with Getter Robo in a package that is more entertaining than either. Compared with Getter Robo, Grendizer is more of a combining robot than a transforming one. That is to say, attaching one of the spazers to the giant robot, as piloted by Duke Fleed, gives him greater powers or more freedom of movement. For starters, Grendizer can't fly, so having a spazer nearby is crucial. Double Spazer (piloted by Koji) massively increases its firepower; Marine Spazer (Hikaru) allows it to fight freely underwater; and Drill Spacer (Maria) enables it to travel underground at mach 9 (!!!). Duke Fleed even has his own spazer capable of space travel. These are functional developments but the real improvements lie in the superior characters with their more interesting interactions, along with less reliance on Go Nagai's characteristic idiotic humour, and reducing the significance of the monsters. The latter, in the guise of "saucer beasts" still make their predictable weekly appearance but, thankfully, their battles are mostly cursory thereby allowing a greater emphasis on the cat and mouse stratagems played between the Vegans and the Grendizer team.

Top: Marine Spazer, Double Spazer and Drill Spazer overfly Grendizer. The team (l-r): Maria Grace Fleed, Koji Kabuto, Hikaru Makiba, Daisuke Umon (Duke Fleed) Daisuke Umon / Duke Fleed is at the heart of the narrative. Unlike Mazinger Z's Koji Kabuto he isn't a clown and unlike Getter Robo's serious Ryo Nagara he isn't dull. (Admittedly, I haven's seen Great Mazinger with a "rash" - to quote the ANN plot summary - Tetsuya Tsurugi as the protagonist.) I didn't warm to him: Fleed doesn't have a single humorous cell in his body, but that doesn't prevent him from anchoring the series. He has something of a late 60s / early 70s hippy aura about him, with his guitar playing, his peace and love idealism and rock star looks. Nevertheless, he embraces his warrior role and readily whacks any female who shows signs of hysteria. His success lies in the older brother sensibility he brings to the giant robot genre, thereby lifting the tone of the series, and in having his back story organically embedded in the central conflict. His maturity - slapping female characters aside - makes him a reliable lieutenant to Doctor Umon and creates a fruitful dynamic with the impetuous Koji. Initially Fleed and Koji are each suspicious of the other, leading to frequent fisticuffs, but Koji's natural ability and never-say-die attitude will eventually win Fleed over. Like an over eager puppy, Koji will, in time, respond positively to the stronger dog's approval. The villains are irredeemably bad, with some notable exceptions. Tetchy Great King Vega wants to rule the universe in the expected unsubtle way of such villains, though some depth is added towards the end of the series as his situation deteriorates, his desperation grows and grief strikes close to home. Leader of the invasion, General Gandal, other than one odd feature, is another by-the-book bad guy - simultaneously a bully and a coward who does the tiresome anime evil laugh as he contemplates victory and grinds his teeth and clenches his fists when that same victory slips from his grasp. His peculiarity is his dual nature. Within himself he has another, female character - Lady Gandal. In the first half of the series, Gandal's face occasionally opens up like a cuckoo clock and the miniature harpy pops out to express her, usually vicious, opinions. Once Shingo Araki takes over the character design role, her appearance is marked by a simple transformation from a male to a female face. When, near the end of the series, the alter egos find themselves irreconcilably divided, General Gandal's violent response is alarming, if effective. Blacki, a regularly appearing, subordinate villain in the first half, would be controversial in this day and age. His name alone would have people wringing their hands. In typical Go Nagai fashion female villains are either nightmares or attractive and conflicted. As always, the latter type are doomed from the moment they appear, inevitably and needlessly sacrificing themselves for the sake of the mostly undeserving male hero they had hitherto fought. The music swells as the hero stares meaningfully into the distant landscape. I roll my eyes. The bad guy I came to like was the science minister Zuril. He was the only Vegan mindful of what was going on, thereby generally coming up with the best stratagems. He was also the most restrained in his villainy and whose motivations stemmed from his character, not just the requirements of the plot or the eccentric imagination of Go Nagai. The almost self-deprecating set of his mouth and cast of his eye softened somewhat the brutality of his mission.

Clockwise from top left. The Vegan leaders - General Gandal, Great King Vega and Science Minister Zuril Kirika, a scientist sent to earth to kill Duke Fleed with her freezing ray. Princess Rubina, Great King Vega's daughter and one-time fiancée to Duke Fleed. (Shingo Araki's style is evident with Kirika and Rubina - think Lunlun and Oscar.) This saucer beast would be right at home in either Mazinger Z or Getter Robo Tokyo Tower cops it again. General Gandal's alter ego, Lady Gandal - she lives inside his face, here opened so she can talk. Splashes of crimson aside, other characters come straight from the Go Nagai inventory. Genzo Umon is a variation on Mazinger Z's Gennosuke Yumi, Danbei Makiba is a not so salacious reprise of Cutie Honey's Danbei Hayami, and Goro is the compulsory cheeky junior schoolboy who appears all the shows of his I've seen. Researching Go Nagai indicates that many of his stock character types go right back to earlier manga. I guess if a formula works, why change it? Character designs, until Shingo Araki comes along, are average to awful, sometimes intentionally so. Araki not only introduces new, more attractive characters, but he also ameliorates some of the awkwardness of the established players, especially the protagonists. It's an irony that the man who had such an impact on the look of shojo anime through Lunlun the Flower Child and The Rose of Versailles would establish his style in such diametrically different shows. Mechanical designs are variable. As only a minor tweak on Mazinger Z's robot design, Grendizer's aura is likewise strong and protective yet sinister. The spazers are effective if hardly groundbreaking, while the Vegan craft are, for the most part, ridiculous. Rather than flying saucers, think flying yoyos. In the case of the saucer beasts the two halves of the yoyo come apart to reveal an animal themed mecha that couldn't possibly have fitted into the space available. Duke Fleed usually despatches them in short time, but not before being racked with pain thanks to their vegatronic rays. Sado-masochism is another overused Go Nagai trope. No victory is achieved without gratuitous agony. A swimming pool episode and tight-fitting flying suits aside, fanservice is limited to Thunderbirds influenced elaborate launch routines and the obligatory combination and separation of Grendizer and the spazers. (I never understood why Duke Fleed was rotated through180º twice while being shunted between the spazer and Grendizer cockpits. Why bother? He ends up facing the same way.) Overall the background artwork and the animation further improve upon the earlier shows, without being particularly notable, other than the incongruous American / Mexican styled ranch and landscape scenery in what is otherwise rural Japan. The civilian characters even dress as cowboys or hombres. Go Nagai's predilection for garish palettes is somewhat muted but still evident. Militaristic or no, the music is a hoot, often being the most fun part of a battle or launch sequence. Less savoury is the valorising of violence and martial ideologies. With the uniforms, the routines, the hierarchical power structures and the embrace of violence, there's an element of fascism not only in Go Nagai's villains, but also in his heroes. Duke Fleed may play Flamenco guitar and wax lyrical about beauty, peace and justice, but he needs little provocation to thump Koji or slap the girls. He professes he'd rather not fight the Vegans yet he'll enthusiasticly indulge in regular mass slaughter of their ineffectual minifos (ie, mini ufos) and, later, the no more effective midifos. (One odd thing is how he, Koji, Hikaru and Maria have finely tuned good-guy radar. They have an unerring ability to pick which of their Vegan combatants have reservations about fighting.) Doctor Umon agonises over turning his research facility from peaceful to military pursuits. For all of two minutes. Thereafter he proudly presents his young charges with ever more destructive weapons. For sure, they are facing the end of the world as they know it, but warfare is presented as a lark, even for fourteen-year-olds. Admittedly, the overall tone makes this a more fun watch than the other shows, but it's precisely because of that element of fun that there's a disturbing undertow. The series was immensely popular with children in Italy (as Goldrake) and France (Golderak). In Italy it created a media fracas where Japanese shows were accused of "promoting fascism, anti-Communism, violence and an unwelcome degree of realism in depicting war" (Pelliteri via Clements) In France there was a similar backlash after it apparently achieved a 100% rating figure during school holidays, which, if true, make it the most watched anime ever by anyone. It became the subject of academic research and possibly the first ever book about anime published outside of Japan, Liliane Lurçat’s A cinq ans, seul avec Goldorak: Le jeune enfant et la télévision, looking at children's reactions to TV programs.

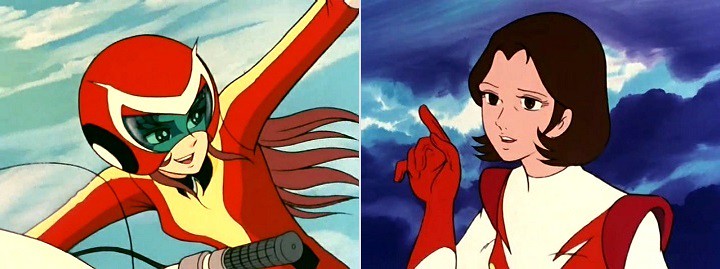

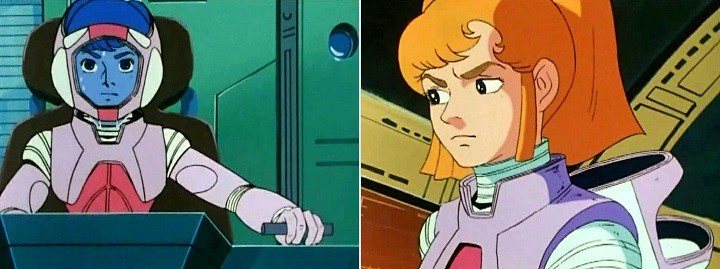

Cowgirls and crimson warriors: Hikaru (top) and Maria (bottom). Hikaru Makiba and Maria Grace Fleed: The greater appeal of UFO Robo Grendizer over the earlier franchises is partly due to the impact these two characters have on the show in general and upon the two male protagonists in particular. Hikaru is, literally, the girl next door, while Maria is the feisty interloper who stirs things up. For the first forty episodes Hikaru plays a subordinate role on her father's ranch. She's sweet on fellow farmhand Daisuke Umon, unaware that he's Duke Fleed, and is irritated when he constantly disappears inexplicably, sometimes in breach of undertakings. She doesn't know, of course, that he's off fighting the Vegans. (Hey, how can any self-respecting ranch hand not take up arms against Vegans. I mean, your livelihood is at Even though Hikaru and Maria prove themselves every bit as capable killers as their male counterparts and even though they are prototypes for future squadrons of beautiful fighting girls, their emancipation nonetheless has its limits. UFO Robo Grendizer is Duke Fleed's stage with Koji Kabuto his crazy offsider. In the second top image above, the two women are in their assigned place - a step behind the men. For the first forty episodes the treatment of Hikaru is patronising, something that lingers, though reduced, as she proves her mettle. This isn't her show, or Maria's. The near contemporary Star of the Seine, which wrapped up the same week Grendizer's episode 12 aired, showed the way forward. It demonstrated how the story of a regular young woman becoming a formidable fighter could make for compelling viewing. Simone is the owner of her narrative; Hikaru and Maria mere players in someone else's.

Genuine affection expressed physically: my favourite moment of the series. I'm a sentimental thing. Rating: So-so. Compared with the earlier Go Nagai giant robot shows UFO Robo Grendizer has better character dynamics and somewhat more sophisticated villains, while continuing his penchant for formulaic plots, dumb monsters, ugly graphics and a questionable take on violence. The whole thing is intended to be ridiculous, but ridicule isn't wit. Overall it was more fun than the older shows, hence the higher ranking. Resources: ANN Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle The font of all knowledge Recommended reading The Mike Toole Show: Saint Shingo ** I've been vegetarian for almost thirty years, by the way. Last edited by Errinundra on Thu Jul 22, 2021 4:09 am; edited 1 time in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

This is the first of four sequels and reboots I'll be looking at before getting back to reviewing originals. On an entirely unrelated matter I've managed to track down more episodes of Rainbow Sentai Robin so that I now have raw versions of all first eighteen episodes. Unless something noteworthy happens in the new episodes I won't update the original review.

A Splash of (very pale) Crimson #9: Yuki Mori

Farewell Space Battleship Yamato Synopsis: While escorting freight across the solar system former crew member of the space battleship Yamato, Kodai Susumu, receives a garbled radio message from the depths of space pleading for help. The message suggests that either the sender or earth are in dire trouble. Military authorities are unwilling to investigate the matter so Kodai enlists the help of the former Yamato crew in stealing the great ship, which is about to be scrapped. They set out for the distant planet Telezart where they free Teresa, an anti-matter being who projects her form as a beautiful human woman. She warns them that a gigantic, rotating interstellar comet is approaching earth. Hidden within its gaseous form is the White Comet Empire that enslaves or destroys every planet it encounters. In another race against time the Yamato must return to battle the empire. Production details: Premiere: 05 August 1978 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #21 Majokko Tickle and Beautiful Fighting Girl #22 Galaxy Express 999) Studio: Group TAC, Office Academy, Toei Director: Toshio Masuda Concept story and general direction: Yoshinobu Nishizaki Screenplay: Keisuke Fujikawa, Toshio Masuda and Hideaki Yamamoto Production design and direction: Leiji Matsumoto Animation director: Tomoharu Katsumata and Shingo Araki among others. Original creator: Leiji Matsumoto and Yoshinobu Nishizaki Music: Hiroshi Miyagawa WARNING: SPOILERS. The very title of the film is a spoiler. In addition I will be discussing the deaths of some of the characters. Comments: With the movie adaptation of the original series outperforming Star Wars in some Japanese cinemas, the creators wasted no time in making this sequel, which follows the basic trajectory of the original: a return journey to a remote planet made under the threat of earth's annihilation in a legendary ship subject to relentless, deadly harassment. As with the Go Nagai formulae, why change something that works? Unlike the Go Nagai anime, though, the narrative is compelling, despite the 2½ hour run time, and even if the title gives away the ending and even if a Chekhov's Gun revealed half way through is clearly the solution to the underlying problem of how to defeat the White Comet Empire. Also inherited from the original series are a disregard for the laws of physics, implausible plot developments, another confounding resurrection, a seemingly sacred reverance for the great ship and a grandiose tone.

Clockwise from top left: Yamato approaches the Great White Comet; Teresa the anti-matter alien of Telezart - a very typical Matsumo character design; The Empress Sabera and Emperor Zwordar; Desslar makes an inexplicable return with a changed personality; and Yamato's Captain Ryu Hijikata is younger, clean-shaven version of Captain Okita. That tone is set from the start. Following a brief, narrated introduction, the Great White Comet appears, spinning with galaxy-like spiral arms and swallowing entire planets that lie in its path. The juggernaut's relentless progress is accompanied by magisterial yet profane church organ chords, as if God's throne in heaven has been usurped by Lucifer. I suggest turning up the volume for this unexpectedly drawn out and visually simple sequence to best experience the impact. For a brief moment, as the organ's first chords assault the listener, I am reminded of Gustav Holst's Mars, the Bringer of War from The Planets, an apt association for the sci-fi conflagration to come. The greater the threat, of course, the more glorious the heroism, the deeper earth's reliance upon and the brighter the aura of the Yamato. It's very name can momentarily reduce to silence the Emperor and Empress of the White Comet Empire (see image above). This is the spaceship, after all, that single-handedly destroyed the Gamilan Empire. By all accounts the franchise's premeditated myth-making was partly responsible for the subsequent cultural significance of the ship in the Japanese imagination. What other nation has fantasised that its greatest warship should become legendary across the galaxy? Don't forget, though, that the original ship was a military failure - sent on a suicidal mission without any possibility of strategic gain in a war for which it had no useful purpose. By redeeming the Yamato (which is a literary name for Japan itself) in a narrative where the ship's sacrifice isn't in vain, are the Japanese trying to redeem themselves? The problem is, the ship, as represented in the film, isn't able to engender the same sense of transendental stoicism so apparent in the original 26 episodes. It may simply be that 2½ hours simply isn't enough time for the ship to suffer sufficiently. Or, that, by the end of the film, the much less interesting Kodai Susumu has stolen the film's focus away from the ship. There's a bifurcation in the narrative that is hinted at in the film's Japanese title Saraba Uchū Senkan Yamato Ai no Senshitachi, which can be translated as Farewell to Space Battleship Yamato: Warriors of Love. On the one hand violence is the necessary solution to the problem the White Comet Empire presents. The movie, in the manner of the original series, portrays the violence in a gripping succession of set piece battles and individual heroism. On the other hand, love is idealised in the abstract (the common good, equality, self-sacrifice for others), the general (the earth, the human race, creation) and the particular (Kodai Susumu and Yuki Mori). The film is unable to reconcile the two poles. In one scene a character may espouse the most noble sentiments; in the next, slaughter their enemy in droves. For the love of earth Kodai will attempt to exterminate the entire White Comet civilisation. For the same reason the ghost of Captain Okita exhorts Kodai to use life itself as a weapon against the enemy, which seems to me a lot like justifying suicide bombers or WW2 special attack units. The split is possibly due to the differing creative approaches of Leiji Matsumoto and Yoshinobu Nishizaki. Matsumoto came to regret some of the creative decisions made, while Nishizaki was adament that to maintain the success of the first film it was, according to his 1977 proposal for the sequel, "necessary to aim for an unimaginably thrilling SF space action drama." He went on to summarise the development of Kodai's character as follows.

He then demolishes his own thesis by adding,

Kodai and the limp form of Yuki Mori. She's not dead yet. Without the scope that a 26 episode television series allows, the characters lack nuance. I'll come to Yuki Mori shortly, but most of the others rely on familiarity from the the earlier series. New characters such as Emperor Zwordar, Teresa the anti-matter woman, or space marine Hajime Saito, never extend beyond one dimension, but that's OK, as their roles are of secondary interest anyway. The Yamato's new captain is Hijikata Ryu (Kodai Susumu lacks the gravitas to pull off the role), a reworking of his predecessor, Jyuzo Okita, though a little younger and lacking the bushy beard. One intriguing return is Desslar (or Deslar or Desler, depending on the source), the Gamilan emperor sans empire, who has by now shown a penchant for dying in battle, then reappearing inexplicably shortly afterwards. So far he's been supposedly killed by the tectonic destruction of Gamilas, by a his own "Desslar" canon in the last episode of the television series, and now in a gunfight in Farewell Space Battleship Yamato. The last we see of him this time is his body floating away in the vacuum of space. I'm sure there's a loophole somewhere. Oddly enough his character has been re-jigged significantly. Where he was arrogant, supercilious and camp, now he's now simply proud. Where once he was dismissive of his enemies, now he admires them. He still treats his underlings as expendable, though. Character designs, with one exception, are prosaic at best. Teresa may have the most eccentric appearance, but, along with Starsha from the original series, will become a template for Matsumoto's feminine ideal that will reach clichéd levels in Galaxy Express 999, which began airing on TV about a month after Farewell Space Battleship Yamato premiered. Similarly the artwork and animation, while benefitting from a higher budget, are serviceable rather than inspired. Gold and yellow tones are frequently emphasised, giving the film a epic yet nostalgic glow. The music recycles the melodies from earlier but with much higher production values and more complex, mostly orchestral, arrangements. The organ theme mentioned earlier, introduced as a leitmotif for the White Comet Empire, adds mightily to the foreboding tone of the film. Yuki Mori: Compared with the original series, where she was largely a pin-up girl albeit highly capable, Yuki's is significantly diminished. Throughout the film she has a melancholy expression that presages her and most other characters' fate. At the outset she is preparing for her imminent marriage to Kodai, which is indicative of her situation thereafter. Secondary to Yodai, she is the embodiment of love, as both the object of Kodai's love and protection, and the expression of love through her devotion to him and her dedication to her duty as nurse to the Yamato's crew. Now pledged to Kodai her fanservice appeal is toned down for the most part - flaunting her body-hugging uniform isn't wifely behaviour, after all.. These traditional and restrictive roles prevent her from doing anything interesting other than throw herself in front of a laser beam to save Kodai's life. There begins the most bizarre element of the film. Structurally, her death is meant to be the catalyst to enable the male hero to make the transition, as per Nishizaki's proposal above, "to a great love for humanity". Instead, he lugs her body around for 30 minutes of the film's run time, finally declaring, as he sails toward oblivion cradling her cadaver, "Let us be married now, amongst the stars of this vast universe." She's dead, for goodness' sake! Rather than the intended profundity the sequence plays out as morbidly peculiar. Rating: Decent. A thrilling journey there and back to a remote planet, under the threat of imminent destruction, makes for a compelling 2½ hours of viewing. Other than improved production values there isn't anything particularly new or innovative compared with the original series, while some odd thematic elements undermine the story's appeal. Because I couldn't take the end seriously, it's rating is a couple of notches below the series. Resources: ANN 2201: Farewell to Space Battleship Yamato at the Voyager Entertainment Starblazers archived website. The font of all knowledge Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle Space Battleship Yamato Wiki Last edited by Errinundra on Thu Jul 22, 2021 4:09 am; edited 3 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

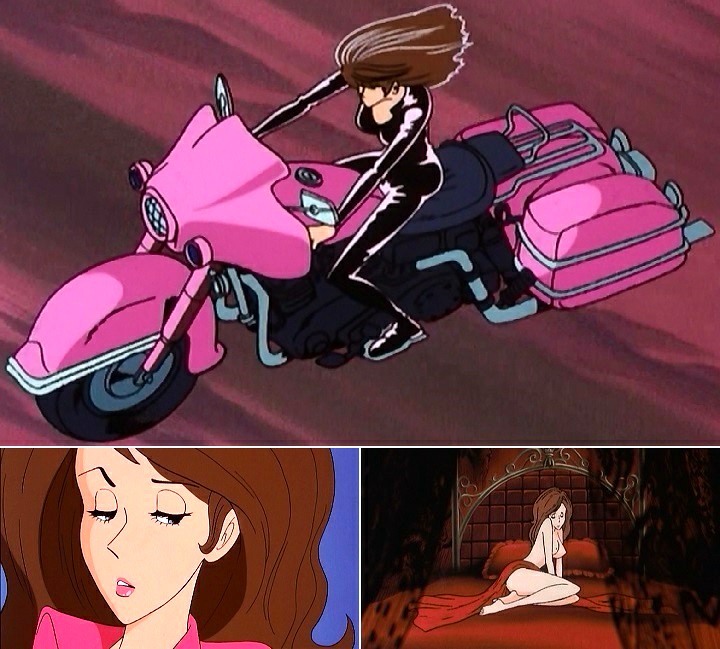

Splash of Crimson #10: Fujiko Mine

Lupin the 3rd: The Mystery of Mamo Synopsis: The real Lupin III has been hanged by the neck until dead, but the real Lupin III is also up to his normal antics as if nothing has happened. His latest caper is stealing the Philosopher's Stone from its hiding place in the Great Pyramid of Giza. Fujiko Mine has other thoughts about that. She's out to relieve him of the treasure on behalf of the mysterious Mamo who has promised her eternal life as a reward. Lupin will have to rely on his mutinous sidekicks, Jigen and Goemon, while the pesky Inspector Zenigata might just clap handcuffs on him if he isn't watching out. And just who was the real Lupin? Production details: Premiere: 16 December 1978 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #22, Maetel, and Beautiful Fighting Girl #23, Anne Shirley) Directors: Soji Yoshikawa and Yasuo Otsuka Studio: Tokyo Movie Shinsha - this was their first full-length feature film Source material: Lupin III by Monkey Punch (Kazuhiko Kato) in Weekly Manga Action, 10 August 1967 to 22 May 1969 Original concept: Maurice Leblanc Screenplay: Atsushi Yamatoya, Jiku Omiya and Soji Yoshikawa Music: Yuji Ohno Character Design: Yuzo Aoki Art: Yukio Abe Animation Director: Yoshio Kabashima and Yuzo Aoki Note: there are four English dubs available on the Discotek release; this review is based on the Japanese dub with subtitles. Comments: After Takahata's and Miyazaki's bowdlerising of the original TV series, TMS - now sans the two famous directors for the film - returns to its roots with, by all accounts, a more faithful rendering of the Monkey Punch vision. Lupin even gets his red jacket back. The result is a racier tone, a more ambiguous relationship between Lupin and Fujiko, more angular character designs and a plot that's considerably more ambitious than was possible in an animated TV show of the time. While revamping those elements, the film adheres to the Takahata / Miyazaki decisions to ditch the hippy / psychedelic / noir sensibility of Osumi TV episodes while ramping up the slapstick humour and zany action. The combination of sexiness, violence and humour works very well for the most part, but the film does fall down in some important ways. I'm going to start with the problems, which aren't fatal to the film's success by any means, and work my way up to it strengths, one of which is Fujiko Mine, whom I'll consider last, in line with my previous splash of crimson reviews.

What's a woman to do when the man who promises so much always falls short? The worst of the problems involve the big bad, Mamo, and the science fiction premise behind his 10,000 year lifespan. The film can be divided into three parts: Lupin's theft of the McGuffin (the Philosopher's Stone); the travails he suffers at the hands of various people as a result, including Fujiko Mine; which leads Lupin to her sponsor at the climax, Mamo, who decides to depopulate the world save himself and Fujiko. Even with my limited exposure to the franchise (two series and two films) it's clear that absurdity is intrinsic to the Lupin experience, but the final showdown and its various settings (especially Mamo's secret city in Colombia - I mean, how do you keep a whole city secret?) seem at odds with the tone of the earlier parts of the film. It isn't dreadful but I get the feeling of being dropped into another film. Mamo himself isn't all that interesting as a villain. Apparently based upon Swan from The Phantom of the Paradise, his bloated face is an attempt to make him seem simultaneously old and young. He's ugly enough to spoil things without being eccentric enough to fascinate. The next quibble also relates to the script and scenario. Jump cuts that are sometimes poorly executed, compounded by plot non-sequiturs and improbable solutions to dire predicaments. Some of the latter are to be expected in a Lupin anime, as if the writers are hitting us with the most outlandish escapades they can manufacture. That's fine, but some of the cuts between scenes are so disjointed, and some of the plot leaps are perplexing enough that I'm left wondering if bridging scenes weren't cut to keep the run time down. (It clocks in at 102 minutes, which is almost 50 minutes less than Farewell Space Battleship Yamato.) First time around I lost track of who was in possession of the Philosopher's Stone. In one scene Lupin has it; the next time it was mentioned - much later - Mamo's research staff are testing it. A re-watch proved that no actual hand-over or theft took place on screen, although in hindsight it was likely taken by Fujiko when she drugs Lupin during one of his seduction attempts. (The result can be seen above.) I suppose that's the nature of a McGuffin. Lupin himself doesn't manage to shake up the show. He starts off well enough with his outrageous infiltration of the Cheops pyramid, but thereafter he's at the mercy of the duplicitous Fujiko and the machinations of Mamo. Mostly he's scrambling to extricate himself from dire straits, instead of confounding the viewers expectations with some hair-brained sting. Jigen, Goemon and Zenigata are largely ornamental - the plot is really just about Lupin, Fujiko and Mamo. Goemon (who has more impact than he was allowed in the original series) and Jigen are good value when they get their allotted screen time, whereas Zenigata is utterly superfluous to proceedings other than comic relief (as if the film needed any).

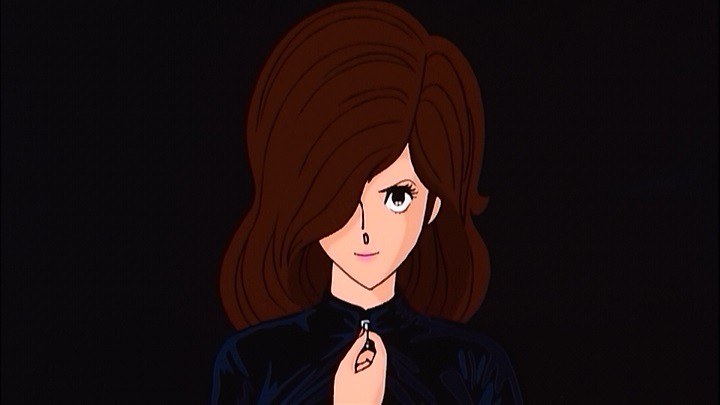

Clockwise from top left: Goemon, Lupin, Jigen, Zenigata and Mamo. Things pick up from there. The minor characters are a hoot. Special Presidential Aide Stuckey - a sour-faced parody of Henry Kissinger - is trying to organise the world to his own satisfaction. His sidekick, Special Agent Gordon is a righteous idiot. Mamo's main goon - aptly and alarmingly named Flinch - looks as thick as two short planks, but he's actually very capable. Everyone will get their comeuppance by the end, except the Henry Kissinger character. He eventually decides to eliminate anyone involved in the debacle, including his loyal subordinate, Gordon. Visual gags are a feature of the Lupin III franchise and this is one area where the film doesn't disappoint. There are big set pieces - the looting of the pyramid, an obligatory chase scene and the destruction and escape from Mamo's lairs in the Caribbean and Colombia. The pick of them is the chase, which involves a helicopter through the streets and sewers of Paris, a rampaging 18-wheeler and a bomb-dropping Cessna. (Elements of the chase sequence will be reprised by Hayao Miyazaki in The Castle of Cagliostro in a year's time.) There are also short, sharp inventive gags such as the Flinch's fractured view of the world after a sword fight with Goemon, or the surprise when Lupin opens the front door to his hideaway. The surprises are sometimes piled up in quick succession as in a scene where a hapless Zenigata is left behind on a jetty as Lupin and crew speed off in a motorboat. He suffers one mishap after another, culminating in a bizarre showdown with his police commissioner. The visual gags frequently involve Lupin and Fujiko. Easily the most eye-popping is when he presses her button, so to speak, setting off a missile attack upon their location. The humour ranges from bawdy to self-consciously surreal. There's even a sequence paying homage to Giorgio de Chirico and Salvadore Dali, a la Osamu Tezuka. Other shout outs include, to give some examples, the abovementioned Phantom of the Paradise, Duel and 2001: A Space Odyssey. The artwork and animation is crisp and bright, thanks to the film's relatively high budget and cel count: 62,000 for a 102 minute film compared with 5,000 for a 25 minute television episode. And with Yuji Ohno now on board as composer, The Mystery of Mamo sounds like a Lupin III movie, which is a good thing. Fujiko Mine: In a return to her treatment in the original pilot film and the Osumi episodes of the first TV series, Fujiko is heavily sexualised, though with a more appealing character design and a softer edge to her personality. On the one hand she is fodder for the male gaze; on the other, none of the male characters are able to control her. That makes her part consumable; part emancipated heroine. I like the innate contradiction. Her principal roles within in the narrative are to behave contrarily and confound Lupin, so I suppose she can't be classified as a feminist beacon. Nonetheless the narrative is at its best when she and Lupin are playing against each other. (Fujiko mostly wins.) She is the standout personality of this particular instalment of the franchise, completely overshadowing Mamo in the role of antagonist to Lupin. That I'm rooting for Fujiko in her rivalry with Lupin is perhaps a perverse reaction as he's supposed to be the site for male identification. As a hardcore male fan of beautiful fighting girl anime, I find myself able, and inclined, to empathise with female characters. I think that's an under-appreciated aspect of what the genre will manage to do by the 1990s. Things are helped along by new seiyu Eiko Masuyama who is an improvement on Yukiko Nikaido. Her stronger voice with its greater tonal variety creates a more distinctive personality. In terms of the grand survey, Fujiko's relatively more adult sexuality suggests to me that she isn't as influential as her Go Nagai counterparts when it comes to the development of the beautiful fighting girl, especially in the comic manifestations that will become so prominent in the 1980s.

Rating: good. For two thirds of its run time The Mystery of Mamo is a highly entertaining romp, full of surreal visual gags, fun characters headed by the sexy Fujiko Mine, nicely animated action sequences and great music. Editing issues have a jarring effect from time to time, while the main villain dampens the fun without increasing the tension as he becomes more prominent in the last third. Don't be put off by that: the film is fun from start to finish; just more so early on. Resources: Lupin the 3rd: The Mystery of Mamo, Discotek ANN The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Recommended reading: Lupin the Third: The Complete Guide to Films, TV Specials and OVAs, Reed Nelson, ANN Last edited by Errinundra on Mon Nov 30, 2020 7:18 am; edited 2 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

The Melbourne International Film Festival is showing two anime films this year: Masaaki Yuasa's Lu over the Wall and Mamoru Hosoda's Mirai. I've got a ticket to Mirai, however both screenings of the Yuasa film are during work hours. Them's the breaks. I also ordered and received from CDJapan the Anne of Green Gables OST (which is terrific) and a collection of songs from The Star of the Seine (not so much). Anime has many strands; this grand survey has given me a whole new perspective into its history.

Splash of Crimson #11: Françoise Arnoul (aka Cyborg 003)

Cyborg 009 (1979 TV series) Synopsis: The series can be broken down into three parts. 1. The arrival of ancient Norse gods controlling golem-like monsters in various European locations, culminating in a showdown between the "gods" and the cyborgs at Yggdrasil, a giant mythical tree somewhere in Scandinavia (episodes 1-9). 2. The re-appearance of the cyborgs' original foes from the 1960's movies, now called the Neo Black Ghosts, presented mainly as a villain of the week scenario (episodes 10-42 or thereabouts). 3. The escalation of the tussle with the Neo Black Ghosts leading to a confrontation with its ruling triumvirate: Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu (up to the final episode 50). Production details: Premiere: 6 March 1979 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #24, Lunlun the Flower Child and Beautiful Fighting Girl #25, Isabelle of Paris) Director: Ryousuke Takahashi (probably best known as the creator and ongoing director of the Armoured Trooper Votoms franchise) Studio: Toei, Sunrise Source material: the manga Saibogu Zero-Zero-Nain by Shotaro Ishinomori, in various magazines, July 1964 - 1981 Script: Akiyoshi Sakai, Haruya Yamazaki, Masaki Tsuji, Sakurai Masaaki, Soji Yoshikawa, Toyohiro Ando and Yoshiaki Yoshida Music: Koichi Sugiyama Character design and animation supervisor: Toyoo Ashida (Heidi - Girl of the Alps (CD & animation director), Space Battleship Yamato (AD & AS), Fairy Princess Minky Momo (CD), Vampire Hunter D OAV (director) and Fist of the North Star (Dir), among numerous other titles and roles) Note: I watched episodes 1-35 via fansubs, whereas episodes 36-50 were unavailable subbed. For the latter I had a choice between an Italian or Japanese audio track. I chose the Japanese version. The lack of subtitles was frustrating as I haven't properly grasped what happened at the series climax and resolution. As with similar cases in the past, this will have affected my judgement of the series.

The PTA villain from the last episode of the original series. 1968 series revisit: (Please indulge me - there is some relevance to the 1979 version.) In my review of the older series I drew attention to the occasional episodes that, with their cold-war scenarios and pointed messages, transcended the otherwise villain of the week formula. The stand-out episode 16, "Ghost of the Pacific", mocks Japan's militarist right wing while displaying images of the Hiroshima Peace Park. The series was broadcast on what was then known as NET, ie Nihon Educational Television Co., Ltd, whose licence required them to emphasise educational programming. The model had proven a failure so the company began showing anime such as Cyborg 009 as part of its regular programming. The political stance of the series upset PTA groups who complained to NET. The company in turn directed the staff to tone down the content. Instead, the staff pulled the pin on the series, ending with a delirious episode 26 where an alien - depicted as an evil, doll-sized PTA mother - leads two superpowers into total nuclear war. By the time the second series aired NET had transformed into TV Asahi, with a regular broadcast licence. Episode 16 wasn't shown again for decades. Comments (1979 series): The immediately obvious change is the introduction of colour along with an accompanying re-design of the characters. To put it simply, they have been bleached. Everyone bar the bald 007 (aka Great Britain) and 005 (Geronimo) has had their hair lightened; some substantially. With the franchise's exotic cast and settings I wonder if these changes were intended to enhance the foreign appeal for both the domestic and possible overseas audiences. In addition, Great Britain is no longer a child while 009 (Joe Shimamura) has grown from shounen to seinen. Both are welcome changes. The uniforms have become, well, uniform. Where earlier Françoise (003) was the splash of crimson and Joe the splash of white in an otherwise purple squadron (in the movies, anyway), all are now in vibrant red with glowing, flowing, impossibly impractical yellow scarves. While I love the colour combination I kept thinking about the fate of Isadora Duncan. I supppose cyborgs don't easily break their necks.

Joe is a little older, a little more the streetfighter There are other changes: some good, others perhaps not so. Along with the colour and the hair styles, the overall appearance has been updated to meet the aesthetic standards of 1979. The character designs retain their overall 1960s goofiness, but, to my 21st century eyes, the anime looks dated without a mitigating aura of strangeness. Rainbow Sentai Robin, by way of contrast, has the feeling of being made by a civilisation lost to time. Character designs aside, the artwork, animation and backgrounds are superior to any of the Go Nagai series I've recently watched, though not in the same league as Lupin the 3rd: The Mystery of Mamo, which, of course, had the benefit of a more generous movie budget. And, on the subject of the Go Nagai giant robot shows, while Cyborg 009 shares their episodic villain of the week structure for much of its run, the individual stories are somewhat more sophisticated and thereby more engaging to this viewer. The series eschews the Cyborg 009 franchise's former penchant for space alien villains; instead giving us Norse "gods" and a trio of taciturn cyborgs whose singleminded desire for chaos runs counter to their supposed intelligence. That cyborgs can be humane, godlike or demonic is a simple message directed at a schoolboy audience. Perhaps I'm being unfair judging Cyborg 009 with my adult sensibilities. That may be why my biggest disappointment is the excision of any overt political commentary. In its place the newer series gives us generalised freedom versus oppression scenarios that have been done to death in all sorts of entertainment media over the decades. The uncontestably evil villains are no longer controversial; they simply want to rule the world by force. Kill the villains and you win the argument. The removal of the earlier show's satirical content suggest the PTA warriors won that particular contest. There are episodes with the potential to make political points, namely episodes 26 and 28 set in the Middle East and Africa respectively. Both end up as mundane action episodes with a conventional antagonist. The creators have also moderated the deliberately fanciful hyperbole of the earlier Ishinimori adaptations while nonetheless attempting to raise the conflicts to epic levels. For a time that worked. The early episodes, where it seemed that the cyborgs were genuinely confronted with beings of divine power, and with an accompanying ominous tone, are the best of the series. The concept of man-made superpowered machines pitted against supernatural beings genuinely tantalised me. Alas, and again, the series squibbs out; the "gods" turned out to be more mundane than I had hoped. I'd love to see an anime where the gods are torn from their heaven. (Is that part of the appeal of Akemi Homura?) Odin, supposedly destroyed at the end of the first arc, makes unexpected, redundant appearances in the last few episodes, reflecting the creators' original aim of finishing with a return to the Norse story line. It wasn't to be. Sunrise pulled out of the production, forcing them to wind up the series prematurely. The resulting rushed climax between the cyborgs, the Neo Black Ghost triumvirate and their saintly alter ego Gandal, lacks the power that may have been achieved had the makers had more broadcast time at their disposal. This problem will become a feature of anime in the next little while, affecting such TV shows as Space Runaway Ideon, Mobile Suit Gundam and Fairy Princess Minky Momo.

The cyborg team (l-r): Albert Heinreich (004); Geronimo Junior (005); Chang Changku (006); Great Britain (007); Joe Shimamura (009); Françoise Arnoul (003); Ivan Whisky (001); Pyunma (008); Dr Isaac Gilmore; and Jet Link (002). Naturally enough, the eponymous Cyborg 009 / Joe Shimamura is the central focus. We get some of his back story, prior to his cyberisation by the Black Ghosts. Turns out he was a delinquent, spending time in a juvenile detention centre until his adoption by a scientist. He's also a champion racing car driver. Delinquent youth and sports star seems to have been a popular combination in the 70s. The parallels with his namesake Joe Yabuki from Ashita no Joe are obvious. 1979s cyborg Joe has gravitated from his earlier Peach Boy incarnations towards the wilder boxing Joe, without ever managing to becoming the latter's charismatic monster. We also get back stories on other cyborgs, namely Françoise (a ballerina), Great Britain (a failed Shakespearean actor), Geronimo Junior in the American west and Jet Link (a New York gang member). Jet takes over from Great Britain and Chang Changku from the 1968 series as the most important character after Joe. This time around he's Joe's best mate, what with their shared former delinquency and car racing rivalry. He also proves himself to be hot-headed in a crisis. The other cyborgs must constantly restrain the American from rushing into battle without thinking. Maybe there's a global political point being made? As one of three cyborgs who can fly - Great Britain can transform into a bird and Ivan Whisky can levitate - and supersonically at that, he is prominent in most battle scenes. As ever, the strongest and weakest character is Ivan Whisky. Strongest in the sense that his psychic powers are near omnipotent. He can predict the future, levitate, teleport people and objects and sense distant activities (thereby rendering Françoise superfluous to needs). He is to this franchise what Yuki Nagato is to The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya: the deus ex machina to be deployed whenever a rabbit needs pulling from a hat. That's one reason he's also the weakest character. The franchise, understanding the problem, limits his power by having him sleep most of the time, something neither he nor the other members of the team can control. This leads to the other reason: a one-year-old super brain just can't leap the credibility gap, both conceptually and visually. His mere existence means the franchise can't ever be taken seriously. Why would anyone, even as demented as the Black Ghost, want to turn a dead twelve-month-old into a cyborg?

Despite being proficient in the martial arts Cyborg 003 spends most of ther time in the background. Françoise Arnoul: Cyborg 003 remains a minor character and a disappointment. She is given only occasional focus and has little responsibility, despite her obvious abiliities. Nor is she given the cheesecake role played by Yuki Mori in Space Battleship Yamato or become the source of sexual tension in the manner of the Go Nagai females. Sure, she's eye candy as a ballerina, but we're talking a few seconds in 50 episodes. Likewise the fist to the solar plexus and the judo throw shown above aren't typical of her normal roles and behaviours. In the first half of the series she spends most of her time at headquarters with Doctor Gilmore and Cyborg 001 as a sort of General Staff to the combatants in the field. As conflict with the Neo Black Ghosts escalates she spends more time on the front line, so to speak. To be fair her wide range of abilities is impressive, but she's no longer a pioneer as a beautiful fighting girl. In 1979 the torch was carried by Maetel (Galaxy Express 999), Fujiko Mine (Lupin the 3rd: The Mystery of Mamo) and Oscar François de Jarjayes (The Rose of Versailles). Kenji Kamiyama will re-imagine her in a spectacular new way in 009 Re: Cyborg, but that's 33 years into the future. Rating: So-so. The introduction of colour and other technical improvements put this series ahead of the first season on most measures, but the franchise's previous 1960s counterculture sensibility has been diluted. The character designs, however, remain resolutely stuck in the preceding decade, while more interesting character and narrative developments were taking place elsewhere at the time. Resources: ANN The font of all knowledge Cyborg 009 Wiki

Go Nagai style unsubtle moment. As Françoise clings to Joe, the scene jumps to the villain's lair. Last edited by Errinundra on Mon Aug 16, 2021 5:09 am; edited 3 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

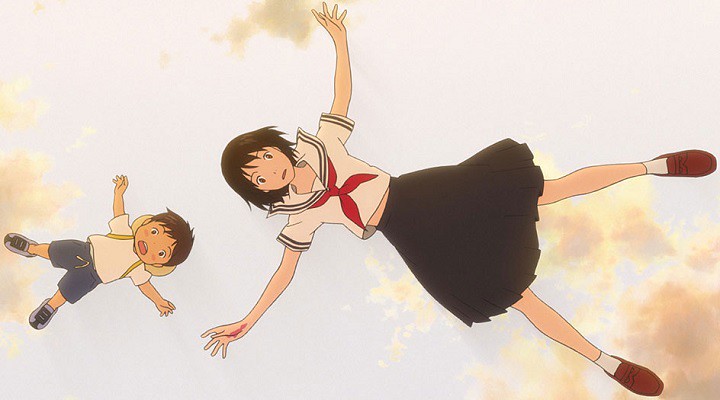

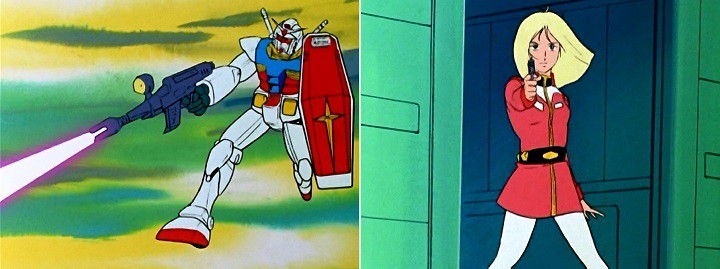

Mirai

Reason for watching: Because it's directed by Mamoru Hosoda, whose career I follow; and because it was showing at the Melbourne International Film Festival. As with other viewings of one-off screenings, please consider this an impression rather than a review. Synopsis: Pre-schooler Kun finds himself demoted from darling to afterthought when his mother comes home from hospital with his new baby sister, Mirai. With his work-from-home architect father too harried and and his nursing mother too occupied to satisfy his cravings for attention, Kun becomes ever more resentful of the new intrusion. Before things get out of hand, Kun has an unexpected visitation from a furry, followed by a future version of his sister. Things get even more hair-raising for Kun when he is transported into the past to meet members of his extended family. A nightmare journey to Tokyo Railway Station reveals to Kun that family ties are deeper than sibling rivalry. Production details: Premiere: 16 May 2018 Studio: Chizu Director / screenplay / creator: Mamoru Hosoda (The Girl Who Leapt through Time, Summer Wars, Wolf Children, The Boy and the Beast) Music: Masakatsu Takagi Character Design: Hiroyuki Aoyama Art Director: Takashi Omori and Yohei Takamatsu Animation Director: Ayako Hata and Hiroyuki Aoyama Comments: Mirai marks the fourth release in Mamoru Hosoda's run of films about family dynamics. In each the routine of daily life is embellished with magical occurences, or science fiction in the case of Summer Wars, that provide Hosoda with the opportunity to explore the relationships in entertaining ways. Mirai doesn't disappoint in that area, although how the magic is introduced, deployed and resolved is somewhat different from his previous films. One of the problems I had while watching the movie was that, not realising the source for the magical erruptions, Kun's experiences seemed to me gratuitous, even forced. In retrospect I've figured that the enclosed courtyard garden was the site of the transformations, both temporal and spatial. I think the issue was my own obtuseness, not any failing on the director's part. That's the disadvantage of a one-off screening in a theatre: I can't re-watch a scene to catch what I'd missed first time around. Irrespective of my own shortcomings, the garden plays the transformational role of the nut from The Girl Who Leapt through Time, computers into the virtual world of Oz in Summer Wars, the wolf man in Wolf Children and the laneway in The Boy and the Beast. You could think of them as portals to a suburban-safe surreal realm of the imagination. Sure, they're mildly threatening places, but they don't visit the darker places of the human psyche in the way the witch's mazes do in Puella Magi Makoka Magica. More a chamber work, the magic world of Mirai isn't as flamboyant as Hosoda's own predecessors, such as The Boy and the Beast or Summer Wars.

Get ready for... tickle torture! (The birthmark on her hand tells the viewer who she is.) The reduced scale makes the film both riskier and less ambitious. The small cast and mostly enclosed domestic setting means that the film relies heavily on the appeal of the characters to succeed. I'll deal with Kun presently, but the others are a mixed bag. Most entertaining are the rumbustious, capering furry and the BMW riding, physically handicapped yet charismatic great-grandfather of family legend. While important to the story - the former announces Hosoda's general thesis while the latter suggests to Kun new ways of approaching problems - neither are central. Less amusing are Kun's unnamed parents. Both are overwhelmed by the responsibilities of child-rearing. His mother, who is the more headstrong of the two parents, becomes, in Kun's imagination, a demonic hag, while his domestically inept and physically unco-ordinated father is a more comic creation. Neither have much depth, although a childhood vignette reveals the mother has some mettle to her character, and a rebellious streak to boot. As a baby, Kun's eponymous sister is little more than a plot device. She has considerbly more narrative and amusement value in her "older" sister form, though she doesn't stray too far from anime schoolgirl norms. How she inveigles Kun to help preserve her marriage prospects is a treat (as is the entire sequence). Their chemistry together is workable without shining. Kun, voiced by 18-year-old female seiyuu Moka Kamishiraishi, is problematic. I get that a teenage female voice is more convincing than a male's for young children of either sex but, for a good portion of the film, I thought Kun was a girl (despite the name and his obsession with bullet trains - hey, I saw the film after a tiring day at work, so clearly my brain was having trouble processing stimuli). The issue was exacerbated by Kamishiraishi sounding both too old and too sophisticated for a three-year-old child, particularly in the second half. The sophisticated speech is, of course, a problem with Hosoda's script, so shouldn't be slated home to the seiyuu. The next issue is inherent in having such a young protagonist. The film makes a brave attempt at getting inside the child's mind, but, while highly amusing, it never quite convinces, leaving this viewer with an adult detachment. It meant that I never had a handle into the film, something that is necessary in a sentimental family dramedy. In short, I didn't invest emotionally in Kun. The third issue is the nature of the magic on display. In his previous four films, the magic / power was identifiably external to the protagonist, enabling them to project themselves beyond normal constraints. Mirai is vague on the matter. Is the source of Kun's visions external? If so, Hosoda doesn't reveal what it is (beyond its possible location in the garden) thereby leaving my curiosity unsatisfied. Is it, then, internal? That's even less convincing. It barely seems credible that Kun could conjure in his mind the events I saw on screen. Don't be put off by my reservations. Mirai does other things well. Above all, it's a funny film. The architecture of the stylish but impractical house is especially suitable for pratfalls, as if Buster Keaton had assisted Kun's father in inflicting the design upon the family. I was amused how parts of the house had adjacent sets of steps separated by a wall. If anyone - think three-year-old - wanted to get to the adjacent area, they would have to go up the steps, then down again. Physical humour is a feature of the film, both in that pratfall sense and in the exaggerated movements and expressions of characters, especially in the magical sequences, something Hosoda has carried over from The Boy and the Beast. The film captures well the physicality yet precarious mobility of a pre-school child. The magical sequences fit in neatly with Kun's otherwise quotidian life, but the viewer is always aware when the flights of fancy occur. The Tokyo Station scene is the most stylised, most surreal and - appropriately - most threatening of the sequences. As the climax of the film and the moment of crisis for Kun, it is more organically embedded in its narrative structure than the analogous parts of Hosoda's three previous films. I always felt the falling satellite in Summer Wars, the typhoon in Wolf Children and the whale's appearance in The Boy and the Beast were tacked on catastrophes intruding upon captivating family dramas and whose sole purpose was to have the films go out with a bang. In Mirai, Tokyo Station becomes both a metaphor for the choices facing Kun and a surreal representation of his state of mind.

Rating: A maybe too generous very good. I want to re-watch Mirai again to better understand some of the narrative elements that I may not have fully grasped. A re-watch would also indicate whether one of its best qualities, the humour, continues to stand up. Overall, a mixture of fun and prosaic characters, a sweet portrayal of sibling jealousy, an attractive visual package and beguiling magical transformations make for an amusing experience. The choice of such a young point of view character may leave the viewer viewing the events in a detached, ironic manner. Perhaps that is Hosoda's intention? Or, maybe its because, having never raised a family, I didn't relate to the events depicted. I'm left wondering who the intended audience is. Resources: MIFF - the images are from their website ANN The font of all knowledge |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Splashes of Crimson #12: Fujiko Mine and Clarisse d'Cagliostro

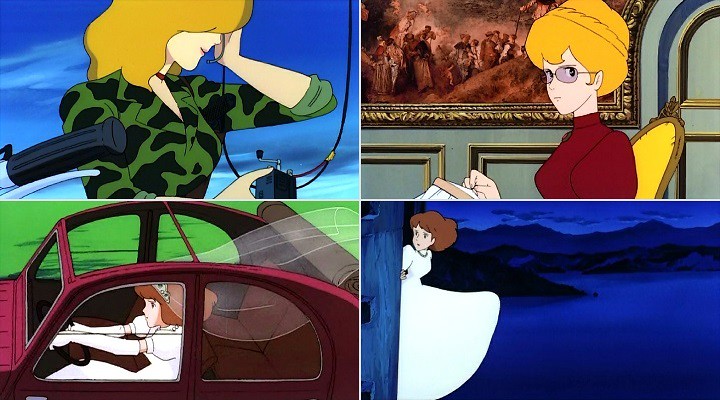

Contrasting images of womanhood: with machine gun in one hand, grenade in the other and the pin between her teeth, Fujiko singlehandedly holds off the villains as demure, marriage-fodder Clarisse is hauled to safety. Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro Synopsis: When his booty from a casino heist turns out to be counterfeit Lupin decides to investigate the rumoured source: the tiny Duchy of Cagliostro. Complication finds Lupin when, en route, he encounters a young woman in a bridal outfit pursued by a gang of men. Turns out Clarisse is the heir to the Duchy on the eve of a forced marriage to her relative, Count Cagliostro. He's got designs on ruling the Duchy and reaping the benefits of its vast wealth potential. Lupin sets out to uncover the many secrets of the castle of Cagliostro. As ever he's assisted by the katana-wielding Goemon and gunslinger Jigen, while Fujiko pursues her own agenda, and Zenigata pursues Lupin. Production details: Premiere: 15 December 1979 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #26, Oscar François de Jarjayes, and Beautiful Fighting Girl #27, Lalabel Tachibana) Director / original story / storyboards: Hayao Miyazaki Studio: TMS and Telecom Animation Film Source material: Lupin III by Monkey Punch (Kazuhiko Kato) in Weekly Manga Action, 10 August 1967 to 22 May 1969 Original concept: Maurice Leblanc Script / screenplay: Hayao Miyazaki, Yasuo Otsuka and Haruya Yamazaki Character Design: Hayao Miyazaki and Yasuo Otsuka Art Director: Shichirō Kobayashi Animation Director: Yasuo Otsuka Music: Yuji Ohno

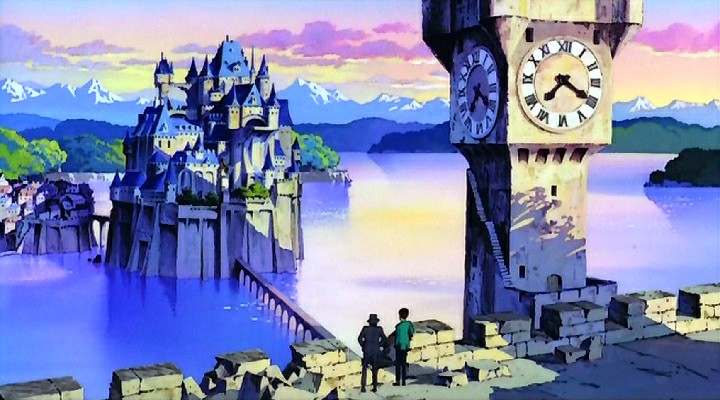

Yasuo Otsuka: My Madman DVD release of the film contains a bonus interview with the animator from 2006. Born in 1931 he worked at Toei from their very first feature animation, The Tale of White Serpent. He gained a reputation for comical villains with his unintentionally humorous skeleton in Magic Boy and came to the conclusion that genuine realism needed to be replaced by "constructed realism" in anime. He went on to be animation director or character designer in Alakazam the Great, The Littlest Warrior, Horus - Prince of the Sun, Lupin III (TV - 1971), the Panda! Go, Panda! movies, Lupin the 3rd: The Mystery of Mamo and Chie the Brat (to name the titles I've reviewed). He later became a trainer at Studio Ghibli and wrote important memoirs of the anime industry of the 1960s and 70s. Otsuka has little time for the modern anime industry, believing that the production system and the ease of modern life stifle creativity. Proud of the original series and The Castle of Cagliostro, he praises Miyazaki's storyboards in particular. He opines that the ensemble characters of the franchise need to be allowed to do their own thing, otherwise it becomes formulaic. He characterises the subseqent franchise as shit trailing behind a goldfish. Comments: Being immersed this time around in 1970s anime, the thing that struck me most profoundly in this re-watch after seven years is how much a technical leap it is compared with its contemporaries. I had a similar reaction when watching Heidi, Girl of the Alps from 1974 for this project. It's no surprise then that Hayao Miyazaki was involved with both. In Cagliostro you can see his meticulous, detailed hand in the layouts and framing that create a spacious grandeur, in the glowing, slightly artificial palette that makes it seem more true and evocative than it would otherwise, and in the jauntily amusing animation and in its sure-footed pacing. It's fun comparing the famous car chase scene with its counterpart from The Mystery of Mamo. They're equal parts fun, but the gags from the newer film arise largely from the animation whereas the older film must depend more on the situations and shout-outs, though it has its animated moments. Cagliostro also lacks the awkward jump cuts of its predecessor, while the fantastical plot developments never fall outside the viewer's suspension of belief. Miyazaki gives us a poised and assured cinema debut.

Clockwise from top left: Count Lazare d'Cagliostro, Zenigata, Goemon, Jigen. Miyazaki also sets his stamp on the much loved ensemble cast. I'll come to the female characters in due course, but, unfettered by other people's vision of the franchise - compare with the 1971 TV series where he and Takahata took over the stumbling series - he can present them as he sees fit. All five of the regular crew are now softer, more rounded in their appearance. Most traces of the previous, deliberate coarseness have been smoothed out: Lupin's hairy skin, the knobbly joints and stick-like limbs, the leering expressions, the nudity and the sexuality. Lupin has gone from the villain of the early episodes of the original TV series, via the unscrupulous rogue of Mamo, to the endearing heart of gold we get in this instance. He's even had his racey red jacket returned to the wardrobe. Even if I were to prefer the more ambiguous version of Lupin all is forgiven thanks to the sheer entertainment of the film's capers. A good example of the softer approach by Miyazaki can be seen in the responses of Goemon, Jigen and Zenigata to Clarisse's sweetness. Goemon and Jigen, whose misogyny is a trope of the franchise, melt when Clarisse thanks them for their kindness. Their embarrassed, self-conscious reactions are a comic highlight. Zenigata gets the best, most sentimental line of the movie when he describes to Clarisse what Lupin has stolen from her. Indeed, Zenigata is a revelation, temporarily becoming Lupin's ally (for a shared, worthwhile goal) and, for the first time, a genuine hero with his righteous defiance of the United Nations. It's this Miyazaki optimism, rather than the Monkey Punch cynicism, that shines in Castle of Cagliostro. And there's no preachiness. Miyazaki avoids his later penchant for overloading his films with thematic density. The villain, the Count of Cagliostro, is a chubbier version of Muska from Laputa: Castle in the Sky. His nuances go no futher than being coldly evil with a taste for refinement. He is a personable fellow so makes for a more entertaining villain than the preposterous Mamo. Miyazaki adds variety through the Count's minions - an obsequious, incompetent secretary, a square-jawed, dumb but capable captain of the palace guard and a gang of alarming claw-handed assassins. The eponymous castle is quite the character itself, with its mysterious plumbing, bottomless dungeons home to a vast array of corpses, and the serried towers.There are elements of Bluebeard's Castle in the setting and narrative, although, as with everything else, the sexual elements are downplayed. Yuji Ohno provides another jazzy soundtrack that is entirely apt. Standout is the sultry, nostalgic opener Honoo no Takaramono. There's also a short piece where both the motif and variations owe much to Mike Oldfield's Incantations album, released only the year before. Ohni, on only his third contribution, is by now a dependable element of the franchise.

Top: Fujiko in Amazon and house-mistress forms. Bottom: Clarisse - ever the damsel in distress. Clarisse d'Cagliostro and Fujiko Mine: The two female characters are weaker elements of the film, which is disappointing given Miyazaki's reputation for quality female characters. Design-wise Clarisse owes a little to Anne Shirley from Anne of Green Gables (though not the personality) and will, in time, become the template for the much superior Nausicaa (Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind) and Fio Piccolo (Porco Rosso). Like the other non-core Lupin characters, she is a typical Miyazaki design. For all his artistic ability, Miyazaki likes to recycle character designs. That's not the real problem, though. Clarisse is a cipher: her roles are prisoner, bride, rescue-object and idoliser. She is sweet, demure, dutiful and quiet. It's as if, uncomfortable with the avowed sexuality of Fujiko, Miyazaki decided to contrast her with his vision of ideal womanhood. If so, happily his vision will expand considerably in future work. Somewhat more interesting than Clarisse, Fujiko has been massively de-emphasised from Mamo. In fairness to Miyazaki, she remains as important as the other two members of Lupin's cabal, Jigen and Goemon. Again it's as if Miyazaki were conducting some sort of culture war within the franchise to have his vision prevail. For the first time Fujiko has no romantic role to play. (She tells Clarisse she dumped Lupin.) Instead she is limited to her characteristic spoiler role in the quest for the banknote printing blueprints. She appears in two forms - as a prissy domestic servant in the Count's employ while she searches for the plans and as a deadly gun-toting Amazon warrior once Lupin starts his mayhem. She's also turned blonde. I guess you can't have two female characters with red hair, which indicates who is the more important to Miyazaki. That said, Fujiko is threatening; Clarisse is sweet. Fujiko has agency; Clarisse has none. Fujiko is active; Clarisse is docile. Although neither are particularly appealing, Fujiko is entertaining because of what she does; Clarisse for what happens to her.

Rating: very good. The Castle of Cagliostro carries its age very well, in part because Miyazaki's remains influential and his key visual styles are established in the movie, but also because it is so handsome. Not bogged down by any of Miyazaki's ideological fixations, the film entertains from start to finish. What might be cliched tropes under a different director are here animated with verve and aplomb. Resources: Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro, Madman ANN The font of all knowledge The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle 500 Essential Anime Movies: the Ultimate Guide, Helen McCarthy, Collins Design Last edited by Errinundra on Mon Aug 16, 2021 5:10 am; edited 3 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Splash of Crimson #13: Olga

Don't be alarmed. Her face is in the process of forming. Space Firebird 2772 (Hi no Tori 2772: Ai no Kosumozo:n, perhaps Firebird 2772: Love's Cosmic Lifeforce) Synopsis: In a brave new world, Godoh is conditioned from the day of his test tube birth and later trained to be a space fighter pilot. His only childhood companion is the faithful, beautiful robot, Olga. When Godoh falls in love with Lena, a woman who has been promised as wife to an up and coming politician, he is banished to the hellish magma mines of Iceland, the hoped for source of energy for a dying Earth. He is given the opportunity of a reprieve if, using his skills as a space pilot, he finds and captures the legendary space phoenix whose blood is reputed to grant eternal life. Assisted by Olga he will battlle the phoenix, bringing incineration, death, destruction, rebirth and renewal. Production details: Premiere: 15 March 1980 (between Beautiful Fighting Girl #27, Lalabel Tachibana, and Beautiful Fighing Girl #28, Chie Takamoto) Original story, story line and general direction: Osamu Tezuka Director: Suguru Sugiyama Studio: Tezuka Pro Source material: Hi no Tori (Firebird or Phoenix) - Tezuka considered the unfinished project as his "life's work"; the film is better considered as a spin-off, rather than an adaptation. Screenplay: Osamu Tezuka and Suguru Sugiyama Music: Yasuo Higuchi Animation Director: Kazuko Nakamura and Noboru Ishiguro (director of Space Battleship Yamato, Super Dimension Fortress Macross and Legend of the Galactic Heroes, among other things)

Olga confronts the Firebird. Notes on some of the names: The Japanese title of the film is 火の鳥2772 愛のコスモゾーン. The final characters ゾーン (pronounced as zōn) are almost always rendered in English as "zone", which makes no sense in the context of the film or the title itself: the phoenix is creation's life force, not a location. Tezuka himself clarified the matter when he explained that it was a play on the classical Greek word for animal, zoion, which, in turn, is derived from the word for life. Tezuka also stated that Godoh's name was inspired by Samuel Beckett's play Waiting for Godot, which may have been flippant, although it might be argued that the earth's renewal is awaiting Godoh's intervention. Olga comes from the Norse name Helga, meaning "holy, blessed". Comments: Born in 1928 in Osaka, Tezuka endured the firebombing of the city in World War 2. He also lived through the subsequent "Japanese Miracle" that saw the nation become the world's second largest economy. Hence, it isn't surprising that death and rebirth are constant themes in his work, or that the phoenix should be such a central figure. You can see the renewal theme in such works as Tales of the Street Corner, Kimba the White Lion, Marvelous Melmo (where the phoenix has an essential role), and the Buddha films, to name some that I've reviewed in this thread. To that I would add my favourite Tezuka quote, What I try to [say] through my works is simple… just a simple message that follows: "Love all the creatures! Love everything that has life!" I have been trying to express this message in every one of my works. For Tezuka, the phoenix is the incarnation of love, the creative force, the bringer of life and death. Hayao Miyazaki would create a variation on the theme with his Forest God / Nightwalker from Princess Mononoke. So, we're talking big themes and big ideas here. Going further, the depiction of annihilation as a precursor to renewal will be played out famously in the next anime I'm reviewing, Space Runaway Ideon, as well as titles as disparate as Neon Genesis Evangelion and Puella Magi Madoka Magica.

That ambition is matched, to an extent, by the film's production. In several scenes the backgrounds are fully animated. Not just panned or multi-planed, but fully painted: when a car drives down a highway, the scenery approaches and whizzes past; when a person moves around a room the walls rotate around them. The exterior shots of Godoh's spaceship - the Shark - are computer generated and the studio avails itself of rotoscoping (though these days the technique has acquired an underserved bad reputation in anime). Space Firebird 2772 is an innovative film for its time and, in patches, an impressive achievement even to this day. At other times it hasn't aged at all well. Many of the characters are stuck in the Tezuka 1950s and 60s design time warp. The musical interludes are reminiscent of the worst efforts of Toei from that same era, although I should be grateful that the cutesy alien animals don't sing. Likewise, the numerous joke scenes as often as not add little to the film other than drag it out. At two hours the film could be much leaner. and, for all the innovation, at times the animation and artwork are just plain bad. As with earlier Tezuka films, there's a mixture of brilliance and poor judgement. The contemporary Castle of Cagliostro is, overall, a better visual experience, but then Tezuka is taking more risks. The scene that, deservedly, gets most notice has 7½ dialogue-free minutes covering Godoh's creation in a test tube, his childhood indoctrination and conditioning, his meeting with Olga and ends with his enrolment at flying school. It's simple, and a visual story telling tour-de-force. If you include the initial images of the phoenix flying and the credits, the first spoken words - which are jarring when heard - are 11½ minutes into the film. Most modern of the character designs - that is it follows the aesthetic fashion of its time - belongs to the protagonist, Godoh. He's a variation on Joe Yabuki (Ashita no Joe), Koji Kabuto (Mazinger Z) and Susumu Kodai (Space Battleship Yamato). As protagonist and hunter of the phoenix he's quite the earnest character. There's a melancholy about him that I suppose the cutesy space aliens are meant to mitigate. Conceptually his role is to destroy his quarry. Tezuka's worldview isn't about eternal life; it's about renewal. The phoenix must be destroyed for the earth to be reborn. Through its sacrifice it creates. Only when Godoh realises how genuinely he loves Olga is he able to subdue the phoenix, which becomes powerless and submissive when confronted with love. Yeah, that's cheesy, but Tezuka's and Sugiyama's conviction manage to pull it off. Just. At the climax of the film, Godoh will have his own phoenix moment, thus embellishing the central theme.

Godoh The film makes extensive use of Tezuka's "star system", whereby he re-uses characters from other stories, but with different contexts, back stories and even names. Think of it as using specialist character actors in live-action films: you've got an actor (or, in Tezuka's case, character design) who plays many roles over the course of their career, but usually of the same type. With a specialist character actor, you know what you're getting the moment they appear on screen. Rapid establishment of character types is essential to anime. In the last couple of decades moe stereotypes have filled much the same function as Tezuka's star system. Still, I find it weird seeing Black Jack as a villain. Maybe that's harsh. His black and white hair informs the viewer that he is ambiguous, and he does the right thing by Godoh eventually. Olga: Setting the animation innovations to one side, the film's best moments usually involve Olga. While she's every bit as serious in demeanour as Godoh, she is treated more comically. Her multiple transforming abilities, while vitally important on several occasions, are humorous. Godoh has a remote control that initiates her transformations. Well, think rapid channel surfing. My favourite moment is when, after saving Godoh from the Phoenix the first time, in this instance in rocket form, she lands, then must shake her nose cone to get her face and hair to re-appear and flick her rocket pods to turn them back into legs. The motions are cute and funny and sexy all at once. Now that's a cue to segue into her fetishy design. On one level Osamu Tezuka is something of a libertarian when it comes to sexuality or, to put it more bluntly, he has the eye of a dirty, old man. That's apparent in Princess Knight, Marvellous Melmo, Tales of a Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra. I like her design all the same. She manages to combine that provocativeness with both a steely hardness and a maternal softness. I see her as a sort of spiritual daughter to Maetel (Galaxy Express 999). That leads me to another common Tezuka trope, which is related intimately to his concept of renewal: female fecundity. Viewing that as paternalistic is certainly reasonable, but there is more going on. Without attempting to justify his approach it seems to me that, to Tezuka, a woman's desirability is rooted firmly in her fertility and that the principal outcome is childbirth. Hence, it follows that the form of male behaviour he seemingly promotes, or at least condones, is ultimately creative, though your mileage may vary on that score. As Philip Brophy explains in 100 Anime: