Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Moving away from romances for the moment.

Warning: This article will reveal the identity of Marnie. You can avoid this by not reading the Personal Reaction section. When Marnie Was There Reason for Watching: Simple: it's Ghibli; it had a general release in Melbourne; and Hiromasa Yonebayashi's previous film, Arrietty was a treat. The Madman dvd release from earlier this year has been sitting on my shelf, waiting for me to get other reviews out of the way. Synopsis: Anna Sasaki is a foster child suffering from depression. Although she acknowledges that her foster parents care for her, she feels she is a burden to them and that their motives aren't entirely selfless - a thought that creates self-loathing within her. Further, although she remembers neither her deceased parents nor her grandparents, she is resentful that they abandoned her in a world where she feels an outsider, something exacerbated by her dark blue eyes. On the recommendation of her doctor - Anna is also an asthmatic - she spends a summer with relatives of her foster mother on the shore of a lagoon in Hokkaido. Across the lagoon is a derelict mansion - The Marsh House - that seems strangely familiar to Anna. It induces a sequence of dreams where she visits the mansion in its heyday decades ago and meets and befriends a girl her own age: the blue-eyed, pale-haired Marnie. When Anna learns that Marnie did indeed live there all those years ago she wonders how this sprite came to haunt her dreams and what the connection between them might be. Long-forgotten memories are awakened when the answer arrives unexpectedly.

Upon meeting Marnie happiness begins to seep into Anna's life. Review: When Marnie was There is something of departure for Studio Ghibli. As I did with the Porco Rosso review I'm going to quote long time Ghibli producer, Toshio Suzuki, from the "Making of" documentary included on the dvd.

Suzuki didn't have a production role for this particular movie, so the context of the quote is that his opinion has been sought about the theatrical release poster - the one with Anna and Marnie back-to-back, holding hands. Suzuki didn't like the poster at first, but has come around. I suspect he doesn't like the movie much, either. Youthfulness aside, the movie looks and feels different from anything previously from the studio. Paradoxically, it is instantly recognisable as a Ghibli production, thanks to its character designs and meticulous production values. How is it diferent? In a word, sombre. Sombre in its design, the colour palette, its story and its protagonist. While it has a joyful ending, Anna's depression hovers over the film. This isn't necessarily a bad thing. Just don't come to the movie expecting the high-spirited wonder so characteristic of Ghibli. Yes, it has magic, wonder and handsome settings but they are comparatively subdued, at all times filtered through the unhappy eyes of Anna.

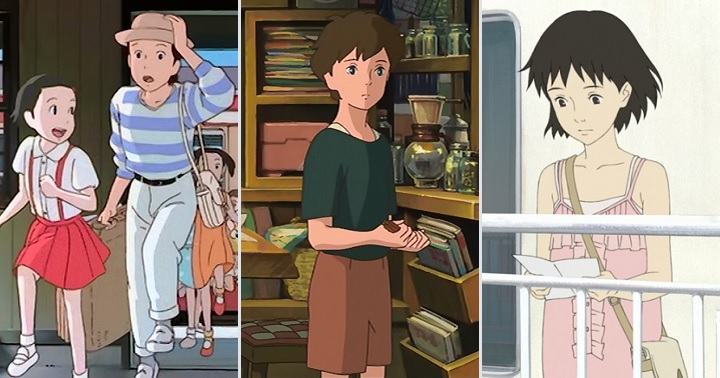

Three spiritual sisters; anxious characters all. L-R: Taeko, Anna, Momo. Anna is one of the few broken characters in the Ghibli protagonist list. I can think of three others. She lacks, however, the humour and irony intrinsic to both the protagonist of Porco Rosso and Chihiro from Spirited Away. The Ghibli character whom she most recalls is Taeko Okajima from Takahata's Only Yesterday. Both Anna and Taeko are "ordinary" people, harbouring grief and resentment. Both will find catharsis over the course of their story. Oddly enough, it struck me pretty quickly that Marnie was telling much the same story as A Letter to Momo. Not just the story, but, even more than Taeko, Anna is the spiritual twin of Momo. In the abovementioned "Making of" director Hiromasa Yonebayashi explains how he brought A Letter to Momo's animation director and character designer, Masashi Ando, into the team specifically to recreate the character expressions from the older film. From Momo he also brought in the director, Hiroyuki Okiura, and six key animators to be key animators in his own film. Comparing all three films I think Okiura's film is the most fun and the most immediately engaging, while its emotional payoff is more contrived. All three characters are rejuvenated by rustic settings. Taeko's and Momo's emotional repair is facilitated by third parties: the farmer Toshio in Taeko's case and the three goblins in Momo's. Anna is more interesting - Marnie is, after all, a figment of her memory - so her repair comes from within. It makes her the most independently strong of the characters. Of course, When Marnie was There will succeed or fail largely on the appeal of the main character and, to a lesser extent, Marnie. I'm not sure that Anna pulls it off. Her development is thoroughly convincing but her humourlessness is unrelenting. In fairness, she's seriously depressed. The film makes up for this by a wonderful sense of place with all its beautiful scenery, the surprising, everchanging tides, the wondrous Marsh House with its visions of days gone by, the quirky characters living around the lagoon and, most of all, with the enigmatic Marnie. The titular character's first appearance is as if she's a young goddess or fairy, with her cheery optimism, her flowing golden hair, her nordic blue eyes, her white nightdress and her bare feet. The seemingly perfect feminine girl, she brings magic into Anna's life. As the film progresses, however, the dreams develop an edge to them: Marnie's cheeriness begins to seem forced, as if her world isn't as perfect as she makes out; and in some she inexplicably abandons Anna. As Anna recovers, the Marnie of her dreams becomes more and more ambiguous and even a little sinister. Without the dynamic between Anna and Marnie the film would flounder. The compelling relationhip that has been established gives the revelation of who Marnie is all the more impact. It's also fun to rewatch the film while paying attention to everything Marnie says and does - it's as if at times she knows what their relationship is - and looking out for the visual hints Yonebayashi sprinkles before the viewer.

Modes of living. Top: Anna and her foster mother's Sapporo flat; the Marsh House. Bottom: the front entrance of the renovated Marsh House; the Oiwa residence. The film also places before the viewer the relationship between people, their environment and their mode of living. Depressed Anna and her overly anxious foster mother live in a generic block of flats surrounded by ashphalt; uptight Mrs Kadoya and her bossy daughter live in a formal Japanese house; the relaxed, generous Oiwas - Anna's hosts - live in a rambling, organic, cluttered (but orderly) accumulation of rooms on the side of the lagoon. Did the people create the houses? Or did the houses create the people? Not a house, but the silo that overlooks the lagoon has an extraordinarily baleful effect on people. Most enigmatic is the Marsh House that, depending on the tide, can be reached by rowboat or by walking across the mudflats. (Anna will eventually discover you can get their by more conventional means - by road to the front door.) The house has three distinct personalities: the grand disrepair as Anna first discovers it; the even grander nocturnal parties of Marnie's parents in Anna's dreams; and the airy, fashionable home for its new residents. Architecture is part of the history of our lives. As are our families. The sadness of Anna's life is that she has lost her place in her family history. Her new foster family cannot give her, she feels, the bedrock of ordinary life that other people have. Hence, she considers herself an outsider. Her home has few accoutrements, as it lacks history. The happy Oiwa house seems on the verge of collapse under the weight of all its history adorning every nook and cranny. The Marsh House enchants because it suggestive of all sorts of pasts. Hisako, the painter, tries to capture on canvas that history before it is changed forever by its new renovating owners. Pivotal to the story is the discovery of Marnie's diary, Hisako's belated acount of Marnie's life and final piece of the jigsaw - a photograph - that finally reconnects Anna with her family history. When Marnie Was There, as its title suggests, is about how the essential presence of family history in our lives grounds us. Without that history we are lost or, at the very least, diminished. This is a film about family storytelling, not in the postmodern way of Satoshi Kon, but in a more nostalgic, emotional way. Personal reaction (highly spoilerific): When Marnie was There is a satisfactory film. Since Spirited Away the only superior Ghibli film is The Tale of Princess Kaguya, while The Wind is Rising would be its equal. Yet it affects me in a way that no other Ghibli film manages to do. I don't think it's due to any universal qualities that the film possesses but more to do with the personal baggage I bring to it. If you don't mind learning a bit about me, read on.

The mish-mash of architectural styles add to the Marsh House's appeal. On a prosaic, architectural level, the Marsh House is very familiar to me, so I'll start off by examining its architecture. Looking at the picture above, and ignoring outbuildings, the mansion has five distinct elements: the basalt base (which I reckon is native Japanese, perhaps a former fort, and predates the rest of the building); the Edwardian (called Federation in Australia) era ground floor; the Victorian era upper floor (with Edwardian eaves and finials); the basalt neo-gothic right wing (again with Edwardian finials); and the more pure Edwardian left wing. The costumes worn in the film's party scenes suggest they are set in the twenties. The three architectural styles were popular immediately prior to that. Melbourne was founded in 1835 but it wasn't until the gold rush of the 1850s that its population and wealth exploded. Thanks to wealth brought by gold, the city oozes grand Victorian era (1837-1901) architecture. Indeed it is named after one of Queen Victoria's Prime Ministers and located in the state of Victoria. The end of the gold rush led to a property bubble that burst in the 1890s. Things picked up again with Federation, which coincided with the new Edwardian (1901-1910) styles. Throughout most of my adult life I have lived in Victorian or Federation houses. I have had bedrooms with fireplaces just like the one above. What's more, especially in the suburbs around where I'm living at present, there isn't much uniformity of style. Many houses blend Victorian and Edwardian features. It gets better. The local stone is bluestone, a form of basalt that looks exactly like the stone used in the Marsh House. It's very hard so not easily worked and therefore isn't cut precisely. This leads to a rough, uneven appearance and the need for mortar. You get the picture. The Marsh House is both magical and familiar. I feel very much at home with it. On a personal level, and with the architecture of the Marsh House as a foundation, there are parallels between Anna's life and my own. Like her I am prone to depression. I understand her reactions to people and situations. I've experienced them. Though never a foster child, my father died before I was born so I partly share Anna's loss. (My oldest sister is also called Anna - she lost her father at the age of 2, the same age roughly as the Anna of the movie. Creepy, huh?). I remember when I was younger standing in front of a mirror with a photo of my father in my hand, trying to make a connection between the two faces. (I couldn't.) Like the film's Anna I am missing family connections. She cannot remember her parents and forgotten her grandmother who cared for her after her parents died until she herself died. I have no memory, nor can I, of my father or his parents. My childhood, however, was full of stories my mother told us children of our father. Only last year I took my elderly mother to see the farm, on the banks of the Murray River, where she lived during that short marriage. Like my mother, Anna's grandmother was a storyteller. When the film joins the dots to reveal that Marnie is Anna's grandmother; that her dreams are her remembering her grandmother's songs and stories; and restores her personal history, it unfailingly shreds me emotionally. Rating: initially excellent but I feel that was inflated by my emotional response. I don't think it's better than Princess Mononoke, which I've rated very good, nor is it on par with the daring Spirited Away. So, for the moment, I'll say it's very good. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 8:32 pm; edited 7 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

This week's housekeeping review was originally posted on 23 January 2012. It's directed by Hiromasa Yonebayashi, who helmed When Marnie Was There. I've spruced up the layout to suit this thread, added a couple of images and, since that date, downgraded its rating to good. I might add that I think that The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, The Wind Rises and When Marnie Was There (all released subsequently) are all better, so my comment below about it being the best Ghibli film since Spirited Away no longer stands. And Princess Kaguya is the exception that proves the Ghibli redhead rule.

Arrietty. (Released in North America as The Secret World of Arrietty with a different dub.) Reason for watching: As part of a major release in Australia (through Madman), Arrietty is screening in 12 cinemas in various locations across Melbourne. One of them - Cinema Nova in Carlton - is screening the Japanese dub with subtitles whereas the others are showing the UK dub. Yes, we speak English in Australia, not American, though some may find our accent strange. Melbourne is arguably the anime capital of Australia and is home to both Madman and Siren Visual. (I live only a short tram journey from Madman's warehouse). Anyway, I trundled down to the Elsternwick Classic yesterday and came away convinced that it's the best Ghibli film since Spirited Away (although that isn't necessarily saying a lot) and that Arrietty is the best Ghibli heroine since Porco Rosso's Fio.

Why do all the best Ghibli and proto-Ghibli girls have red hair? Think Nausicaa, Fio, Clarisse and now Arrietty. Synopsis: Arrietty is a Borrower: a tiny human living with her family beneath the floorboards of a house belonging to regular-sized humans. They "borrow" discarded items, using them in creative ways: a kettle as a boat, a clothes peg as a hair tie or a pin as a sword. When Arrietty befriends Sho, a regular-sized boy, she exposes her family to danger, necessitating a move to a safer haven. Comments: The English dub is appropriate, simply because the original Borrowers is set in England. Ghibli's take is fascinating, though. They have deliberately mashed up English and Japanese cultures. To whit, the setting is a mostly English house with a smattering of Japanese features; it has an English garden with Japanese monuments; the borrowers keep their original English names while the host humans have Japanese names; when the human family has dinner two of the characters eat a traditional Japanese rice dish with chop sticks while the third has meat and three vegies using a knife and fork; when you see text on screen such as books or signs, sometimes it's in English and other times it's in Japanese. (The American version gives the human family English names, completely missing the sly multi-cultural joke.) The weirdest thing - pointed out to me by my sister - is that the cars drive on the right hand side of the road, which is at odds with both England and Japan. I have to admit I missed that detail so I have to take her word for it. It's also odd that Spiller looks like an American native. I must say I really appreciate Ghibli's perverse non-conformity. Getting back to the marvellous red-headed heroine, Arrietty is competent, self-confident and perhaps a tad serious. Her voice actor, Irish woman Saoirse Ronan is nigh-on perfect in the role. Geraldine McEwan as the scheming maid Haru isn't far behind whereas Olivia Colman's Homily is perhaps too over-the-top in her hysterical timidity. I found the slow enunciation of the male characters - Sho and Pod - distracting, as if their scripts didn't properly synchronise with the lip flaps.

The cat proves to be smarter and more helpful than it might seem on first impression. The film is at its best in the first half when Arrietty, alone or with her father Pod, explores the wonders of the garden or the seemingly cavernous human house. Not only is the wonder of her world exquisitely observed but we get to see our own world through an entirely new perspective, with clever visual and sonic observations on things we take for granted. The friendship between tiny Arrietty and human Sho is sweet and platonic, but the development is so succint that it didn't succeed in getting me emotionally committed to it. It's as if the makers were so enchanted by the world of the borrowers that they lingered there just a little too long. I, for one, liked it that way. The film is not so effective in the second half. The exploration takes a back seat to the plight of the borrower family as they contemplate their compromised secrecy and their future security. The action isn't particurlaly exciting and the sense of wonder is overtaken by events. Beyond Arrietty none of the characters have the presence to carry the unfolding drama. The penultimate scene isn't as wrenching as it may have been, thanks to the not totally convincing bond between Arrietty and Sho. The music is perfect. Breton Cécile Corbel’s Celtic harp is a revelation for a Chibli production. What could be more appropriate than a Celtic harp for a film about the little people? Rating: very good Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 8:43 pm; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

phia_one

Posts: 1661 Location: Pennsylvania |

|

||

|

I've seen some clips of the UK dub for Arrietty and I like it much better than the US one. None of the VAs fit the characters in my opinion.

To me, what really made the movie was the music. It's just so relaxing and I thought it did a good job of pulling me into the movie. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Next weekend and the one after the Japanese Film Festival rolls into Melbourne. I hope to give first impressions of Miss Hokusai, The Case of Hana and Alice and Ghost in the Shell: The New Movie. This week I'm going to look at a couple of taboo-breaking series. Today's new review is an old favourite of mine. It isn't a RomCom but it is the best love story I've yet seen in anime.

WARNING: I'll be freely discussing the major hook of this anime, (which, I'm sure most people know anyway), along with other plot developments.

Nanoka's sweetness goes a long way in undermining any negative reaction to her choices. Koi Kaze Reason for watching: It has been a long time since I first watched this anime but, as far as I can remember, Theron Martin's reviews and the promise of a serious take on incest, had me intrigued. It has never been released in Australia so my first attempt at ownership turned out to be a shitty quality bootleg from SE Asia. In due course I replaced this with the Geneon version from Right Stuf. It has become one of my most re-watched anime series. Synopsis: Fifteen year old Nanoka and twenty-seven year old Koshiro are sister and brother who haven't seen each other since their parents' divorce when Nanoka was pre-school age. Not recognising each other, they have a chance meeting amongst windblown cherry blossoms (Koi Kaze = "love breeze") leading to a visit to an amusement park and a Ferris wheel where they candidly reveal their emotional inner selves. Their subsequent shock when they discover they are siblings is compounded by their parents' plans to have Nanoka move in with Koshiro and his father to bring her closer to her new school. They each struggle to reconcile their romantic and sexual feelings for the other with their familial relationship and social expectations. Despite, or perhaps because of, their genuine feelings, over the next twelve months they are inexorably drawn further and further into what must surely be a doomed relationship. Comments: This is a possibly alienating anime. If a sympathetic exploration of incest doesn't sit well with your moral compass then it may not be the series for you. At the other end of the scale, if your taste in anime runs to imouto/onii-chan comedy hijinx you may be disappointed by its serious take on the trope. Either way, if you avoid Koi Kaze you will be missing a thoughtful, beautifully written series from director Takahiro Omori (Hell Girl, Baccano!, Natsume's Book of Friends, Durarara!! and Princess Jellyfish, to list just the ones I've seen). This series doesn't pull its punches yet it always manages to treat its most difficult subject matter with finesse and sensitivity. At the centre of the story are two engaging characters: Nanoka Kohinata (taking her mother's family name) and Koshiro Saeki (taking his father's). Nanoka is beautifully portrayed on the cusp between childhood and adulthood. Her childishness, her vulnerability - she is dwarfed by Koshiro - her inexperience, her bewilderment at both Koshiro's and her own emotional behaviour are reflected nicely in her character design and how she is animated, often transcending the production limitations. Her appearance can be captivating: the image at the top of the post is an example of how inherently sweet she can be. At other times the adult comes through. My favourite example is from the iconic Ferris wheel scene where their compartment disappears, Nanoka's hair blows in the wind and, for a moment, you see the woman within her as she touches Koshiro's head. Just brilliant. An earthy example of her latent sexuality is another early scene where, dressed only in shorts and red camisole, she is clipping her toenails whilst, unkown to her, Koshiro gazes at her unconsciously displayed female form. In a series where all the other characters are notable for their indecisiveness, Nanoka will show her mettle (whether misguided or no) when she pushes her relationship with Koshiro to its consummation, and is the more comfortable of the two with it, and in her dismissal of Kaname Chidori in their showdown beforehand. Her cheerfulness and her ready bemusement are in stark contrast to Koshiro's morose and irritable behaviour.

Suggestions of the woman Nanoka will become: subject and object; self-aware and unselfconscious. For his part Koshiro is a more difficult character to like. Part of what makes him interesting is that he is a much more empathetic character than his brusque, short-tempered exterior suggests. He tells us he chose to work for a marriage agency because he enjoys bringing people together and watching their relationships develop. His act of kindness in retrieving Nanoka's dropped train ticket attests to his innate good nature. In the defining Ferris wheel scene he demonstrates to Nanoka his underlying sensitive nature when he comprehends the similarities between their plights, as well as his ability to judge his own behaviour and his admiration of her straightforward, honest feelings. It is a gentle side to his nature that Nanoka will recall when Koshiro later treats her meanly and arbitrarily (or so it seems to her). In truth, his angry outbursts arise because he is unable to deal with his growing sexual attraction towards his sister. What's more, for the first time in his life he discovers that he loves someone from the bottom of his heart. (After dumping him his former girlfriend, the kill-for gorgeous Shouko Akimoto, wonders if he ever could.) He is weak. He doesn't want to let go the the possibility of having sex with Nanoka but nor does he want to hurt her by setting limits to their relationship. Perhaps he should: he is the adult person, after all. Instead he vents his frustration upon her, cruelly at times. He moves out of home to avoid, rather than confront, the problem and stumbles when Nanoka appears at (or, rather, trips over) his doorstep.

A flattering image of Koshiro. Normally he appears rougher and intimidating. He needs to shave more. Best of the support characters is Koshiro's office manager, the straight-talking, feisty, big-drinking, likeable Kaname Chidori. If Shouko has the looks that Koshiro ought to be lusting after then Kaname has the personality. Not only that, but in time we will learn that she is sweet on him also. (Likewise, Shouko would probably take him back if only he showed he cared for her.) The perceptive Kaname is one of only two people to get an inkling that things could be going astray with Koshiro and Nanoka. In effect she becomes our moral touchpoint, clearly laying out to them both the dangers of their incest. Despite her best rhetorical efforts she is no match for the stubborn Koshiro or the determined Nanoka. What would you do in her situation? Dob your friends into the police? Their parents? I would probably do as she does: try my best to dissuade them, then leave them to the consequences of their choice. The other person to sense what's going on is Nanoka's best friend: the loyal, unlucky-in-love, uncertain Futaba Anzai. In a series that abounds in sharply observed or contrasted moments, her statement that she is too scared to find out the identity of Nanoka's secret boyfriend brings home how chilling the situation has become. If Kaname Chidori is the good angel doing everything she can to prevent Koshiro and Nanoka from making a terrible decision, then Koshiro's co-worker, Kei Odagiri, is the bad angel. He is bearable as a sleazebucket character because, for the most part, his latent paedophilia is so clownish. He does, however, highlight two of the strengths of the series. Firstly, a series dealing with incest could so easily be tasteless. Odagiri is cleverly portrayed to constantly remind us of this, thereby paradoxically helping it avoid this very pitfall. Second, and more importantly, we condemn him from the start for his apparent paedophilia even though he never carries out his fantasies (if only, perhaps, through lack of opportunity). Yet we more readily forgive Koshiro for doing precisely what is abhorrent in Odagiri. Thus, the viewer becomes complicit in Koshiro's and Nanoka's actions.

Kaname Chidori, Futaba Anzai & Kei Odagiri: different viewpoints on the protagonists' transgression. Odagiri's ironic role is just another example of the exquisite script driving the anime. The genius of the script is apparent on several levels: the way it adroitly handles the potentially squicky subject matter; the beautifully constructed characters of Nanoka and Koshiro; the psychological insights into their behaviours; and the slow development of the affair that never strains credibility yet inexorably leads to its final outcome. Its greatest genius, however, is, as suggested above, to make the viewer complicit in the transgression of the protagonists. When Kaname desperately tries to prevent Koshiro from taking a step too far, a part of me is hoping she loses the argument. And, because Nanoka so successfully wins my sympathy, that same part of me would rather she achieve her heart's desire than conform to society’s expectations. It's not as if the script is condoning their behaviour. Time and again there are ironically juxtaposed scenes, quietly placed contrasts or visual editorials. When Koshiro sniffs Nanoka's bra he comes across as sleazy but when Nanoka is twice aroused by Koshiro's smelly work shirt she doesn't seem sleazy at all. Koshiro repeatedly reasures potential marriage club members that all people are thoroughly tested so that anyone they meet is completely safe. Except the staff members, perhaps? Koshiro drags himself from their first-time post-coital bliss to tell their father via the telephone not to worry about how late it is because Nanoka is staying over at his place. The next morning they go to the local park and throw mud at each other. Later, after hours, they climb into the Ferris wheel and pray together that it will move, to recreate that original moment together, as if the world would move to suit them. (They are unaware that their father, who happens to own the amusement park land, has decided to redevelop it as a shopping mall.) Most poignant is the last episode visit to their mother where she reads out a school essay of Nanoka's dreams, that includes living together again with her mother, father and big brother, becoming a hair stylist like her mother and eventually taking over the business, getting married and having lots of children. All gone. This understandably leaves the two nigh on suicidal. (Oddly enough, for all its potentially controversial subject matter, the one episode that was withdrawn from the original broadcast was an earlier one dealing with the divorce. In Japan, it seems, divorce is more taboo than incest or suicide.) If the series doesn't approve of their actions, neither does it condemn them. The two characters are so sympathetic and their story so meticulously crafted that I also found it impossible. I am left hoping they can manage the best they can in an extremely difficult situation. Difficult perhaps, but the series doesn't end in calamity. Instead we leave the two lovers, as close to each other as ever, facing an unmapped and uncertain future. We can only wonder what will become of them.

Contemplating suicide: he dithers but the more practical Nanoka moves on. The artwork and animation reveal the limitations of the production's budget. Backgrounds are basic, movements are awkward and the characters are variable in their appearance. That doesn't matter so much with Nanoka, whose variable facial features sit easily with her changing clothes and hairdos. This is a show where demonstrating the state of mind of a character is more important than design consistency. That said, Koshiro is dstractingly off-model at times. Nevertheless, talented director that he is, Takahiro Omori uses his resources effectively and Koi Kaze more than makes up for any visual shortcomings with an inspired use of music (except the awful end theme) and, importantly, silence. Omori has continued to work with many of the same people over the years. One under-acknowledged collaborator is composer Makoto Yoshimori. Here he uses a plaintive, melodic style, unlike the more upbeat numbers of Baccano! and Durarara!!. The music always suits and enhances the feel of the series. Yoshimori is a composer who is particurlarly sensitive to the work he is embellishing and doesn't impose his sound on a series in the way, say, composers like Kenji Kawai or Yuki Kajiura are apt to do. I prefer the Japanese dub to the American dub simply because in the Japanese version Nanoka is voiced by the appropriately aged Yuuki Nakamura. Tiffany Hsieh sounds like what she is, an adult mimicking a child. Patrick Seitz, however, does a fine job as Koshiro. Rating: Masterpiece. Anime's best love story, partly because it is so beautifully written but also because of its sharp edge that, along with the writing, prevents it from becoming formulaic or sentimental. The subject of incest is treated with a maturity not normally seen in anime, so that much of the anime's power comes from the viewer's complicity in Nanoka's and Koshiro's transgression, courtesy of the two being such sympathetic characters. The open ending may disappoint some but I think it is entirely apt. Further reading: Theron Martin's thoughtful reviews. DVD 1 DVD 2 DVD 3 Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 10:20 pm; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Key

Moderator

Posts: 18454 Location: Indianapolis, IN (formerly Mimiho Valley) |

|

||

|

Probably goes without saying that I agree with every single word. Definitely interesting seeing another perspective on this, as you put into words some observations that I vaguely picked up on but never articulated (such as how the series displays Nanoka's latent sexuality). I said on ANNCast a couple of years ago that this is the best-written anime series that I've ever seen, and nothing I've seen since then even comes close to contradicting that.

Oh, and for anyone not already aware of this, Tiffany Hsieh = Stephanie Sheh. I think this was one of her earliest prominent performances. |

|||

|

|||

|

Akane the Catgirl

Posts: 1091 Location: LA, Baby! |

|

||

|

Hey, Koi Kaze is on my list of anime to see! I'll probably check it out next year, if I have the time. Thanks for your review! Really, thanks. (My current favorite romance is Spice and Wolf, and I'd like to see your thoughts on Holo and Lawrence.)

Also, I just posted my Sailor Moon analysis post. Can you update the title? I'd be very grateful if you do. |

|||

|

|||

|

Key

Moderator

Posts: 18454 Location: Indianapolis, IN (formerly Mimiho Valley) |

|

||

|

To put it into perspective, if Koi Kaze is my all-time #1 for writing then Spice and Wolf is somewhere lower in my Top 5. As romances go, the two have substantially different strengths; whereas S&W's appeal lies in the byplay between the two leads, KK's strength is in the way it analyzes its two leads and their situation.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

I would add that Spice and Wolf adds two extra layers onto its unmatched comedic byplay between Holo and Lawrence: the four stories around Lawrence's economic misadventures; and the overarching mystery about Holo's origin. You could say it's a RomCom++. The treatment of the situation between Nanoka and Koshiro in Koi Kaze makes it the better love story. They would both be in my top ten anime, but, as Key says, for different reasons.

BTW, Akane, there are links on the first page of this thread to my initial responses to the two S&W seasons. They will be added as posts in this thread, probably sooner rather than later, in one of my midweek housekeeping updates. I want to get all my masterpiece rated anime included in this thread. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

This midweek housekeeping review is an expansion of the original post from 6 July 2011, including the synopsis I wrote for my nomination in the Best First Episode Tournament, some pics and extra text.

Sasameki Koto Reason for watching: I was intrigued by the glowing assessment of the first episode after stumbling across Carl Kimlinger's review of the first six streamed episodes. I'd never seen a yuri anime before and, at the time, it was available for Australians on Crunchyroll. This was my opportunity to dip my toe in the yuri pond, so to speak. Within that one episode I was hooked. Synopsis: Sumika Murasame is sports champion, dux of her year, class president and admired by everyone. Tall and be-spectacled there is one thing she isn't: "kawaii". That's a problem because Sumika loves her best friend, Ushio Kazama, a self-proclaimed lesbian who won't even look sideways at another girl unless she rates highly on the adorable scale. Afraid that a confession of her love will end their friendship, Sumika watches on in agonised silence as Kazama hunts for the perfect cute girl. Of course, for her part the clueless Kazama is blissfully unaware that her best friend is, in reality, her true heart's desire.

Sumika gazing at Kazama with just a hint of paranoia. This yuri anime has a remarkable first episode that isn't much of a guide to the rest of the series. If that episode were an OAV on its own I would rate it as excellent and be tempted to give it a masterpiece ranking. The writing and structure are perfect gems - every moment adds something to the overall story. The characters, especially the lead Sumika Murasame, are nuanced with each gesture and word meaningful, be it the movement of fingers as Sumika and Kazama hold hands, or the sudden intake of breath by Kazama when a teardrop slides down Sumika's cheek, or the trembling hands of a love-smitten student. Sure, it's corny but it's very well done. Standing above all this (literally and figuratively) is Sumika, one of my all-time favourite anime characters. Intelligent, capable and genuine but not above behaving quite badly towards her best friends and / or tying herself in knots over how to express her love, she is a multi-faceted, sympathetic creation. Then everything changes. In the second episode, the already basic animation retards even further and subtlety is replaced by face faults, deformation and shouting. Nuanced writing gives way to absurdity and cheap laughs. The worst part of it is that it diminishes the carefully wrought intimacy of the first episode.

Tomoe and Miyako show Sumika and Kazama how it should be done. It's not all bad. Things improve when the tomboyish, mature Tomoe is properly introduced into the series. She adds an impartial stance for us to view Sumika's and Kazama's delusions while nudging them ever so gently together. She is also the only character to ever outwit Sumika or out-perform her at sport, thus making the latter even more sympathetic. Tomoe comes as a package with her pint-size fake-princess lover, the intentionally unpleasant Miyako Taema, whose main role is comedic editorialising. She simply isn't funny enough to succeed. Diminutive, softly-spoken class vice-president Masaki Akemiya is the sucker who cops most of the misfortune dished up by the series. Sweet on Sumika and knowing she's lesbian, he dresses as a girl to catch her attention. When his overly hormonal, nose-bleeding younger sister sends pictures of him to a fashion magazine he quickly becomes their top "female" model. Other characters have no qualms about using his cross-dressing talents for their own ends, which invariably involve him being humiliated time and again. Straight girl Kiyori (both in her comedic role and sexual preference) doesn't do much other than eat (how does she remain so skinny?) until episode 11 when she stitches up ratbag Miyako and all-too-serious self-deluding Azusa Aoi by subjecting them to a sequence of sickening amusement park rides. Hearing the spiteful Miyako say, "Oh Jesus!" as she's about to go into freefall is almost as good as seeing Izaya getting punched out in Durarara!!. Aoi, while neither an appealing nor significant character, does have some poignant moments where, as with Sumika and Kazama in that memorable first episode, she illustrates the loneliness and tangled strategems of a young lesbian trying to find a place in an, at best, indifferent world and to identify like-minded people. When Sasameki Koto does that sort of thing well, it is an outstanding series.

Aoi, Kiyori & Miyako. No sympathy for the latter, though I love the way she enunciates that profanity. There are other comic moments that make this worth watching, even if it isn't the first rank. Akemiya's cross-dressing gets him into some diabolical scrapes while Sumika's fear of coming out does likewise, though nowhere near as humiliatingly. Pick of the comic moments is the Strauss Waltz iced tea disaster in episode 10, brought about by Sumika fantasising about Kazama's bikini strap failing. It's just this sort of goofiness that makes Sumika anything but aloof, despite all her abilities.

Magazine model Akemi, aka Akemiya. Kazama has a crush on the former. The latter has a crush on Sumika. The creative team may have realised that they got it wrong because in the latter part of the series, they cut back on the annoying bodily distortions and the writing becoming more sensitive even if it doesn't to return to the levels of the first episode. Disappointingly, the final episode, while it is clear that Kazama truly loves Sumika, doesn't properly resolve the romantic tension between them. That isn't altogether surprising. The show is a tease, like the manga it comes from. (The anime only covers the first 13 chapters of the manga and it takes until chapter 36 for Kazama to admit she loves Sumika.) The manga was published in the seinen Monthly Comic Alive. It's clear that this a yuri series for a male audience, especially when you consider how the character designs are intended to please male viewers. You could say it's a regular seinen romance where a girl, Kazama, doesn't go for boy sports jocks like Sumika. Indeed, Sumika - as she is actually presented - is quite the tomboy. As mentioned above, her lusting after Kazama can seem more male than female. Describing Sumika as simply a re-constituted male diminishes her, though, as she is a marvellous female character. What is diminished is the story's polemical reach. It's hard to imagine its male audience identifying with the plights of the young lesbians. I suppose Sasameki Koto may engender sympathy for the female characters. It did with me. Another facet of the anime is its class distinctions: Kazama lives with her struggling writer brother in a tiny apartment; Sumika's father runs a large, historic dojo. In other words, not only is Sumika accomplished, she is also from a wealthy samurai bloodline. Just as well she's a down-to-earth character. Anyway, it's an interesting dynamic that isn't ever fully teased out in the anime. A pity.

Sleeping together on the train after a big day out. Sweet. Rating: Good. Sasameki Koto never again matches its singular, poignant first episode. It does manage, thereafter, to get by on the strengths of its main character, Sumika, its humour and the occasional return to the dilemmas and loneliness faced by young lesbians. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 11:00 pm; edited 2 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

It has been a long day. After work I walked into the city to meet some friends to take part in a climate change rally ahead of the Paris Climate Summit. The police said there were about 40,000 people; the organisers 60,000. You get the ballpark figure, but certainly nowhere the numbers for the 15 February 2003 anti-Bush/Blair/Howard invasion of Iraq rally in Melbourne (150,000 - 200,000). There you go: now you know my politics. After the march three of us had dinner in a noodle cafe in Chinatown and then I was off to the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Federation Square. Yep, the Japanese Film Festival (JFF) has finally rolled into Melbourne.

During the pre-screeing ads, there was an announcement that ACMI would be showing Princess Mononoke in December, using the original 35 mm print. If there's one anime film that I've longed ot see on the big sceen (and the ACMI screens are certainly that) then this is it. Anyway, on with the show. It's already 1.00 am and there's another film, The Case of Hana and Alice, this evening. Because I'm not long home from seeing Miss Hokusai, and given its episodic nature, this will be more a set of impressions than a formal review. The anime images are from the JFF website. [Morning after edits]: I've cleaned it up a little to remove some typos caused by my previous sleep deprived state and to better express some of the things I was trying to say. I've also added the paragraph about the visuals. Miss Hokusai Reason for watching: I could. The JFF has shown a few anime in recent years: the two Buddha movies based on the Tezuka manga (the first was good, the second weak); the Otomo anthology Short Peace; and Tamako Love Story. I didn't bother with that last one. After watching the first episode of the TV series Tamako Market I just couldn't stomach sitting through the entire series then watch a movie.

The film brings to life these and other paintings by Miss Hokusai's father. Synopsis: Covers a year in the life of the famous Edo Period artist Hokusai through the eyes of his older daughter, Oei, also a talented artist. We meet other artists of varying ability, art dealers, prostitutes and patrons in the teaming streets and alleyways of Edo (now Tokyo). We also meet Oei's younger sister, the blind and ill Onao, who depends upon Oei to "show" her the sights of Tokyo. Comments: Miss Hokusai has an impressive track record at festivals and competitions, culminating in the best animated feature at the Asia Pacific Screen Awards in Brisbane earlier this week. It is based upon the manga Sarusuberi, which, according to the font of all knowledge - Wikipedia - is a collection of unrelated short stories. This is reflected in the movie, a series of slyly intelligent tableaux, all featuring Oei, a conscious decision by director Keiichi Hara to give the film coherence. Oei is a forceful, serious yet eccentric character. She suggested to me what Ohana's grandmother, Sui Shijima from Hanasaku Iroha - Blossoms for Tomorrow, may have been like when she was nineteen years old. Her pouting lower lip also suggests wilfulness, self-centredness and petulance. She is a better character, however, than that might imply: her generous, loving care of her ailing sister belies that lower lip. She is an instinctive painter, who, when inspiration arrives, can rapidly produce works of power and flawless technique, exemplified by a large painting of a dragon done in a one night rush. When she labours over her work the results are more prosaic, more flawed. Nevertheless, the film favourably compares her with all other artists of Edo with the exception of her father, whom she tolerates so she can learn from him. She follows Hokusai on his peregrinations amongst the lowlifes of Edo to absorb a life precariously yet richly lived. Characteristically she looks on inscrutably as her father turns each scene on its head. The setting is a kind of Japanese version of the Paris Left Bank. The young Hokusai is keen to improve herself as an artist. In one amusing sequence, after being told that her portraits of women were technically superior to her peers' yet lacked sensuality because of her naivete, she visits a female prostitute to be shown a world of sensual pleasure. The hard-working courtesan promptly falls asleep in Oei's arms.

Oei has a droll, petulant air. She doesn't suffer fools gladly. Hokusai senior has the genius's ability to see clearly into the heart of things. His analysis of the ability of his daughter and his peers and rivals is unerringly accurate. There is more, though. He can see the ineffable otherness of people and paintings and objects - things that have a powerful, unconscious affect on our state of mind. In one example a businessman buys a painting by Oei that gives his wife nightmares. Hokusai explains to Oei that the painting has loose ends, makes the necessary additions and releases the woman from her ordeal. In another instance he enables Oei and his apprentice to visualise a courtesan's mental anguish as an attempt by her head to escape from its body as she sleeps. It isn't just them he convinces: he plants the image into the courtesan's mind as well. It's no wonder that Oei follows him around, despite her apparent exasperation; everywhere they go is a new experience for her. Not only does he have a unique vision, but he can get other people to see it as well. Unlike his daughter, he can churn out work of great skill without waiting for inspiration, including erotica - apparently much sought after by many different segments of that society. The film provides a poignant and obvious contrast to Hokusai's vision in his younger daughter Onao, who is blind. Her blindness disturbs him, as if it is a malignant thing that could deprive him of his ability. The loss of his genius is a fear he reveals in the courtesan sequence mention above. For her part, Onao understands her father's reluctance to visit and sees herself as a destroyer who deserves to go to hell. Vision is life; blindness is death. Oei repudiates this view, patiently and lovingly taking her younger sister around Edo, to feel, hear and smell the life all around. Scenes where Onao lies face down in the snow or when Oei gently places Onao's hand in river from a moving boat are magic. For all Hokusai senior's vision and technical ability there are still alternative ways to experience and understand the world.

Oei and Onao. How we see the world is subjective. I have no idea whether or not Oei is a fictional character. One of the curious, largely unexplored, themes of the film is that neither Hokusai nor Oei seem much concerned about her gaining recognition for her work. The film makes it clear that her peers and at least one art dealer know her style along with her strengths. It also has her completing her father's commissions under his name, even the popular erotic portraits of women. The implication being, that if she actually existed, she may have painted many of the masterpieces attributed to him. The name of the film - Miss Hosukai - is even a reference to her being one part of Hosukai the painter. The catch is, she doesn't make an issue of it with the result that the film doesn't explore the idea in any depth. Visually, the film is all Production I.G. class with several exceptional and magical sequences where Hokusai senior's art or artistic vision is given imaginative expression on the screen. Nineteenth century Edo is intricately depicted. An early panoramic view of a busy street, with teeming people moving every which way, nicely sets the standard of avoiding the sensation that the named characters are the only people in an otherwise ghost city. For sure, it is a romantic depiction of Edo, but it is a grubby, scented, active one. Grubby, but also alluring. For a lovingly recreated period film, the music is thoroughly western in its style and instrumentation, reminding me that this is, after all, a work of artificiality. Rating: very good. Miss Hokusai is a sophisticated, adult movie exploring genius through the eye's of the daughter of one of Japan's most celebrted artists. An entertaining cast explores themes of family and artistic vision in a Bohemian environment through a series of loosely connected but entertaining episodes. It doesn't provide answers but neither does it hit the viewer over the head with preaching. It is a worthy recipient of the numerous awards it has won.

The studio. Neither Oei nor Hokusai clean up after themelves. They move whenever a place gets too dirty for comfort. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 20, 2019 11:37 pm; edited 5 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

This evening I was back at ACMI for the next instalment of the JFF. The start time - 6.45pm - was much more civilised. Two hours later as I stepped out into Federation Square I was greeted by orange and mauve stripes adorning the skyline. Again the pictures are from the JFF website.

The Case of Hana and Alice Reason for watching: As before. I could. Synopsis: Following the separation of her parents Arisu moves with her mother to an outer suburban location, but things don't start well in her new life. At school she is bullied because she occupies the seat of a boy, apparently named Judas, who disappeared, maybe even murdered, the year before when his four supposed wives discover the existence of the others. She is creeped out even further by someone spying on her window from a neighbouring house. Realising that the two may be connected she confronts the Peeping Tom, a shut-in named Hana who had been in Judas's class. Despite the unpromising start the two quickly find common ground. They decide to track down the truth about the missing boy, leading to a sequence of misadventures across the city involving, among other things, a gullible taxi driver, a kindly old man, four generous punks, a sleeping truck driver and a bevy of schoolboys hoping to get a glimpse of a car accident casualty. Comments: Long-time live action director Shunji Iwai turns to animation for the first time as director in this prequel to his 2004 teen romance movie, Hana And Alice, using the actresses Yu Aoi and Anne Suzuki to reprise their roles. The choice to go with animation is obvious: having actresses approaching 30 playing 14 year olds just isn't going to work. Funnily enough, they do act the roles: the film has both rotoscoped backgrounds and characters.

Arisu the ballerina in school uniform. In this sequence the film breathtakingly switches to outlined animation. The rotoscoping works well on the big screen. The interior backgrounds have a real life detail and messiness while the exterior backgrounds have perfect, infinite parallax. This latter quality gives the film a sense of space and movement foreign to more traditional anime, while avoiding the blocky look you sometimes get with CGI generated backgrounds. The rotoscoped characters also succeed, avoiding the twitchy bodies and blanked out faces of their counterparts in Flowers of Evil (though that anime is intentionally seeking to unsettle the viewer). The beauty of rotoscoping is that Iwai has real cameras at his disposal, allowing him to accurately record people's movements. No other anime I've seen so acurately displays someone running at full speed or performing a ballet routine. One extended running scene highlights Arisu's feet as she's chasing her father's taxi: the way her feet impact the ground, the way the forces are transmitted, they way her feet flex, arch and lift is glorious. It's something anime rarely gets right and never, that I've seen, so beautifully. The ballet dancing sequences go further and combine tracking camera shots with exaggerated animation to again highlight the beauty of the movement. The downside is that real cameras cannot easily do the things that the virtual cameras of CGI animation are able to. In one instance Arisu races wildly up a switchback staircase in her house with a virtual camera following her body closely. The change to CGI is obvious: the backgrounds empty and Arisu's movements seem artificial. I like the rotoscoping but, if you prefer the on-screen imagery to stick closely to anime norms, this film may require some adjustment.

This running sequence is marvellously done. The rotoscoped tree shadows, with their parallax obeying behaviour, add to the marvel. The most important, and the most memorable, element to the movie is the developing chemistry of the titular characters. As the point of view character we get to know Arisu much better. She is a believable mix of naivete and schoolyard scepticism; embarrasment around adults and unselfconscious ease with her body when dancing or running (she's talented at both). More the follower than the leader, she makes up for it with her gift of listening to other people's point of view, a gift that quickly wins the trust of the taxi driver, the old man, her former acquaintance Yuki, the classroom exorcist and, of course, Hana. She's a toughie, though. She takes no shit from a boy who tries to bully her alongside a railway line, even managing to turn the situation to her advantage. (Bullying is an ongoing theme of the movie.) She is also prepared to take on an entire classroom, and makes a good fist of it. Hana is quite the oddball. Her idea of a love letter to a fellow student is to send him a marriage certificate filled out with their personal details. Needless to say, things don't turn out well. She devises madcap schemes then relies upon Arisu to carry them out. Like Arisu she's a toughie - it's clear these two are going to be a formidable combination and, because they are so likeable, it's a pairing guaranteed to have the viewer barracking for them. Anime sometimes struggles to develop chemistry between characters. I think it's because on-screen chemistry isn't simply in the conversations that characters share but also they way their bodies converse. At best, seiyuu may record their dialogue together. Otherwise it is up to the talent of the animators to convince us of the authenticity of the relationship. With rotoscoped animation two actors are physically interacting and it's clear that Yu Aoi and Anne Suzuki work well together, not just in those moments when they're in physical contact but also in the way the hold themselves in the presence of the other. They are a fun pair.

Hana and Arisu learn the answer to the final mystery. If I have a complaint, it's that the film takes too long for them to meet. The set up of the scenario, whilst concerning Hana - though we don't know it, takes too long. That reflects the nature of the narrative: even when Arisu and Hana start working together the plot proceeds in a series of slowly developed gags. They're fun and quirky, but there's not much urgency or drama. I wonder if The Case of Hana and Alice will continue to entertain after multiple viewings. Is the chemistry of the two leads enough to pass continued scrutiny? I don't know, but I'd still like to own it on dvd. This is a good-natured film. One of its tricks is to introduce threatening characters then reveal them to be anything but. The class exorcist forces a ritual upon Arisu then later admits that she did so to help her fit in (and even admits that she faked an episode of being possessed in order to become the class exorcist to stop herself from being bullied). Arisu and Hana meet a gang of punks in a ramen shop. When the punks realise that the girls might miss the last train while waiting for their order they offer their own newly arrived meals. An old man initially seems a pervert and and abductor but soon shows his true, sweet nature. Shunji Iwai not only directed the movie but also scripted it and wrote the music. He's quite the polymath. The music is melodic, though it frequently gives the impression I've heard it before. Rating: very good. Appropriately and effectively used rotoscoping; a winning performance between the two lead actors, genial story telling with droll observations, and a sequence of gag situations combine to make a highly appealing film. Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Sep 21, 2019 12:13 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

This week's housekeeping review comes from the first Japanese Film Festival I attended. Like the two posts immediately above, it was written and posted when I got home from watching it on 1 December 2011. Unlike them it's brief. (I must be getting worse as I get older.) As usual I've updated the format and added two pictures from the trailers for the films. I've also added some notes at the end regarding the sequel, which I saw a year ago today at, you guessed it, the 2014 JFF. And, yes, you may notice if you do some simple detective work that I've plagiarised myself again. I've since downgraded the rating to decent.

More on the ACMI's Essential Anime program. Six films are being shown in mid-December: Princess Mononoke, My Neighbour Totoro, Laputa: Castle in the Sky, Boruto: Naruto the Movie, Dragon Ball Z: Resurrection "F", and Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo. I really couldn't sit through Eva 3.0 again - it completely tanked compared with 2.0 - and the two shounen films aren't my cup of tea. I've never seen anything from either franchise. Are they worth the admission price of $13.00 each? I intend to watch the Miyazaki films, of course. Buddha: The Great Departure Reason for Watching: I've just got home from seeing this film at the cinema. It was shown as part of the Japanese International Film Festival which has just rolled into Melbourne. I only found out about it this morning, thanks to a death nell news item at ANN AU. Arietty is showing on Sunday but I suspect it's already sold out.

Prince Siddhartha: troubled by the world he sees, despite his privileged life. Synopsis: Covers the early part Buddha's life where, as the Prince Siddhartha, he is heir to the Shakya kingdom, which is constantly at war with the more powerful Kosala kingdom. Siddhartha's father tries both to raise as him as a warrior leader and to shield him from the miseries of the world. Of course, he is successful at neither and the young Buddha eventually renounces his privileged life to seek a greater understanding of the world and its obligatory suffering. Comments: The film is based on the manga by Osamu Tezuka and is a fictionalised account of the Buddha's life. Several of the principle characters - Migaila, Chapra, Tatta - are inventions of Tezuka's, which isn't a bad thing at all as the three have strong and memorable personalities, whereas the historical characters, including Siddhartha, are wooden by comparison. Siddhartha's wife was altogether too much one of those Tezuka cutesy Betty Boop look alikes to be taken seriously. For a film with pretensions to grandeur it is surprisingly mundane in execution at times (possibly due to budget limitations) and some of the dramatic scenes fall flat. In one death scene the "dead" character unexpectedly lifts her head and starts talking before having the good grace to finally expire properly. It came across as quite odd. These failings are more than compensated by other dramatic scenes that work well and, thanks to the giant screen and quality sound system, some stunning vistas and sound effects. Some of the battle scenes just won't be the same on a home system no matter how good. The film didn't flinch from the presenting the cruelties of life, including those inflicted upon children and women. Nevertheless, it faithfully captures the optimism that is such an essential element of any Tezuka work. The source material is so rich and so extraordinary that even a ham-fisted portrayal would have some merit. This version is much better than that but sometimes falls short of what it may have been. Rating: Good. **** David Cabrera wrote a dismissive review here at AU and, frankly, I think he's right. For me, the occasional grandeur of the imagery and battle scenes, along with the impact of the soundtrack was sufficient compensation for the weakness in the script. Whatever merits the film has would be diminished at home. Seeing the sequel - Buddha 2: The Endless Journey - also diminishes it. The newer film cuts back on the grandeur of its predecessor while expanding on its mediocre elements. Some of the monk's training scenes border on slapstick while the characters have become, I can only hope, unintentional parodies of the people they are supposed to represent. As I said above, I've changed the rating of the first film to decent and the rated the second as weak. I'm not at sure if it's worth perservering with the series.

His head changed shape. Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Sep 21, 2019 12:28 am; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

With Ghost in the Shell: The New Movie screeing at ACMI tomorrow afternoon (Melbourne time) I thought I'd write about the other film I saw at last year's JFF. I've since purchased the Hanabee DVD release.

Short Peace Possessions Combustible Gambo A Farewell to Arms Reason for watching: I had downloaded a raw rip of Combustible and, while I kind of liked it, I figured it would be pretty impressive on a big screen. It was a no-brainer once the JFF announced it would be screened at ACMI. Comments: Every few years the anything-but-prolific Koji Morimoto and/or Katsuhiro Otomo collaborate with other directors in making anthology OVAs/films. They're strange, very Japanese things, ranging from three to nine segments, sometimes with little obvious connection between the segments and often out of step with prevailing anime fashions. Among them have been Robot Carnival (1987), which I've yet to see, Neo Tokyo (1987), Memories (1995), The Animatrix (2003), Genius Party (2007), Genius Party Beyond (2008), and now Short Peace (2013). The content of the segments is quite an eclectic mix, both in subject matter, although they frequently have a science fiction theme, and in quality - ranging from absolute stinkers like Limit Cycle from Genius Party to the incomparable Magnetic Rose in Memories (with a script by Satoshi Kon). The theme of Short Peace - according to the font of all knowledge, Wikipedia - is Japan at various points in its history. The are two futuristic settings (including the opening credits) and three historical pieces. Violence is another linking theme: weather and unappeased spirits (Possessions); a conflagration (Combustible); demons (Gambo); and warfare (A Farewell to Arms). Given that none of the segments are set in the present time then the title, Short Peace, is presumably an ironic reference to the Japan of today. Other than that they are tonally and stylistically very different. Opening Credits - directed by Koji Morimoto (Magnetic Rose, Beyond, Dimension Bomb)

Rather than be terrifed by the surreal apparitions, the girl finds them wondrous. With several nods to Rintaro's opening segment Labyrinth from Neo Tokyo, a girl playing hide and seek is sucked into another, surrealistic world where she is possessed by a sphere of light that enables her to rapidly and continuosly transform her appearance. This short intro is a reprise on Morimoto's altogether superior Dimension Bomb from Genius Party Beyond. Once again he indulges his penchant for surrealist imagery, which sits well with the needs of the film - we are entering a world of the imagination where anything can happen - but is altogether too brief to amount to anything worthwhile on its own. There's some nice images here but, as with the rest of the film, if you approach this with an expectation of state-of-the-art animation, you will be disappointed. As a rule, Morimoto's segments are, for me, among the highlights of the anthologies but if you want to see how good he can be then track down the three I've listed above the image, from Memories, The Animatrix and Genius Party Beyond, respectively. Possessions - directed by Shuhei Morita (Tokyo Ghoul, Coicent, Freedom)

An umbrella frog enlists the help of the pedlar. A travelling pedlar/handyman finds himself lost in a mountain forest at the height of a storm. He finds an isolated, deserted shrine but as he settles down for the night he is disturbed by discarded, damaged human artefacts, come to life, clamouring for his attention: sun shades, kimonos and kitchen utensils. He must use all his wiles and skills to appease their spirits. After overcoming my initial dislike for the brutish, cgi design of the main character, this has become my favourite segment of the film. It has an optimism and generosity of spirit absent in the other segments (and, come to think of it, much of the rest of these anthologies). The thing that will hit the viewer first is the way it inverts the common anime technique of placing simple 2D characters in a cgi background. Here Morita has a 3D cgi character in a painted setting, though there are moments where the backgounds are also cgi. The household goods dragon at the end is beautifully done, the spirits possessing the abandoned objects are a fun mix of the sinister and the quotidian, while the pedlar's gruffness belies his good nature. Both actors have great voices for the role, particularly Jason Douglas in the English language dub. Possessions was nominated for the best animated short in the 2013 Academy Awards. Combustible - directed by Katsuhiro Otomo (Akira, Steamboy, The Order to Stop Construction)

Owaka: burning with grief. Childhood nextdoor neighbour sweethearts Owaka and Matsuyoshi are separated when the latter's wealthy father disowns him for carrying out his ambition of becoming a firefighter and wearing the tattoos typical of his occupation. The grieving Owaka accidentally sets alight her family's wood and paper house, leading to a conflagration that threatens the city. Matsuyoshi joins the battle to save the city, along with Owaka. The story is simple, the metaphors are obvious: what whe have here is Otomo spectacle. That's a good thing. I've never much liked his sour worldview and when he gets thematically ambitious the story telling suffers. Even more than his near contemporary, Mamoru Oshii, Otomo is at his best when his visual genius is unleashed. The story is told in the form of a rolling parchment scroll, an engaging trick that allows him to start with a panaoramic view a la Hokusai (see review above) then, as the scroll turns, the field of view narrows until we find ourselves in Owaka's garden. The segment comes into its own once the fire gets going. In the cinema the sights and the sounds, especially the non-stop pounding drums and crashing bells, were nigh on overwhelming. The characters don't amount to much but that hardly matters. What it lacks in complexity it more that makes up for with its effectiveness. Gambo - directed by Hiroaki Ando (Five Numbers!, Ajin)

If anime is to be believed polar bears have replace dogs as humankind's best friends. Next we'll have people jumping into polar bear pens in zoos. When a demon abducts girls from a terrified village, the last remaining girl enlists the help of a wandering samurai and a giant white bear, Gambo, to defeat it, leading to a brutal fight between the two monsters. Perhaps Gambo is hitching a ride on the success of Polar Bear's Cafe. How is that polar bears have to come to symbolise power and nobility for the Japanese anime audience? For that matter, since when have polar bears lived in Japanese forests? I can excuse those weird and wonderful things but more problematic is just how ugly and unpleasant this segment is. The deliberately primitive art style is unappealing; the battle between the demon and the bear is vicious; and the supposed cutenss of Kao, the girl, comes across as contrived. This is the weakest of the four main segments, yet it provides the most enduring images of the anthology. A Farewell to Arms - directed by Hajime Katoki (mecha/mechanical designer for the Gundam franchise)

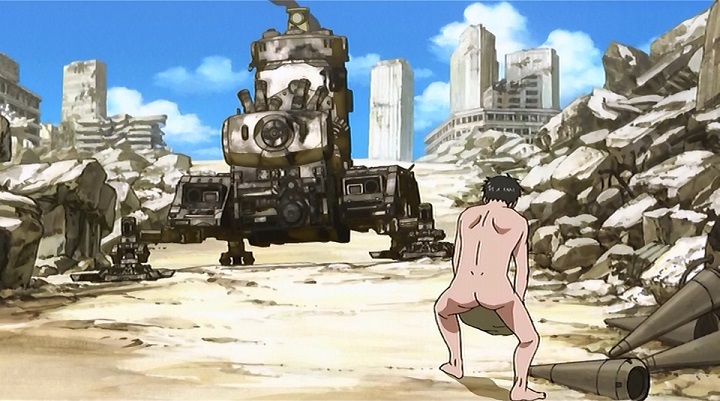

Human stripped to the bare essentials v tank robot in all its pomp. In a post-apocalyptic greenhouse warmed world, a mobile platoon encounters a rogue autonomous robot tank while recovering a nuclear warhead. The segment is adapted from a manga by Katsuhiro Otomo. Farewell's visual style is the least adventurous of any of the segments but it more that makes up for it with its superb animation, escalating drama and brilliant sense of timing. Sure, it's just a battle between humans using their wits and a terrifying, indestructible robot, but it is done with elan. It bothers me, though, how entertaining the battle is; how much it appeals to the viewers' pleasure in destruction and death. The same thing happened with the motorcycle scene in Akira. Given its Otomo provenance it isn't surprising that it is eventually mediated by a philosophical punch line, so to speak. A typically sarcastic and ironic one at that, but you'll have to watch the film to find out what it is. (The screenshot is a hint.) Rating: I find it difficult rating these films. The segments simply don't have enough time to have much stature while their diversity prevents the overall film from making any sort of polemical or narrative point. As a result I tend to rate them harshly. Possessions: good Combustible: good Gambo: so-so A Farewell to Arms: decent Overall: decent+ Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Sep 21, 2019 12:57 am; edited 2 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

This week's housekeeping review isn't part of the Japanese Film Festival but it's the other anthology mentioned in my last post that I've reviewed - this time from 27 March 2013. I've upgraded the pictures, normalised the layout and cleaned up some of the syntax.

Labyrinth Tales aka Neo Tokyo Labyrinth Running Man The Order to Stop Construction Reason for watching: I watched the third segment of the this three part movie series from 1987 a couple of years ago. MAL doesn't list the segments separately so I've had it lying in the imcomplete list all this time. I decided it was about time I got it shifted into my completed list. Comments: Labyrinth - directed by Rintaro (the original Kimba the White Lion under the name Shigeyuki Hayashi, Galaxy Express 999, Metropolis) Led by a French circus clown, a small girl and her cat take a trip through the imagination in a series of sometimes arresting tableaux that, in the end, don’t add up to much at all. With one glaring exception it is nicely animated while the atmosphere is simultaneously fun and creepy. The segment morphs through several stylistic changes, one of which is so redolent of the evolution sequence form Bruno Bozzetto’s Allegro Non Troppo that I suspect the whole thing is a homage to European animation. (This is the third anime I’ve seen with an obvious nod to Bozzetto’s masterpiece.) The segment introduces and frames the other segments.

One of these images is courtesy of Bozzetto; the other Rintaro. You guess. Running Man - directed by Yoshiaki Kawajiri (Ninja Scroll, Highlander: The Search for Vengeance, Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust) In a futuristic car racing competition one driver, Zach Hugh, who has the ability to psycho-kinetically destroy inanimate objects around him (and thereby his opponents’ cars), crosses the line between life and death through sheer will power. Yes, it’s loaded with Kawajiri grotesqueries (which, at the same time, seem mundane) while, thankfully, there are none of his statuesque but repellent looking women. It all gets a bit silly at the end, although the final destruction of Hugh’s car is poetry in motion and probably my favourite sequence in the entire movie.

The private detective investigating where Zack Hugh gets his enduring power from. The Order to Stop Construction - directed by Katsuhiro Otomo (Combustible, Steamboy, Akira) In the aftermath of a local coup, a Japanese salary man is sent to the jungles of South America to stop a giant construction project that has been taken over by robots who will not allow mere orders to stop them completing their assignment.

If you've ever wondered where Justin Sevakis got his avatar... Like most of Otomo’s work there is some wonderful hand painted animation and glorious scenery here. Yet, like the previous two segments in this anthology, there are moments of glaring shortcuts. I’ve never warmed to Otomo’s works. As with Kawajiri’s grotesqueries, Otomo’s satirical posturing lacks any ideological foundation to give it any point. It’s there because it gives the viewer a thrill. You could call it satire porn. The visuals are superb but the theme of robots taking over is oh so worn out. The main character, a buck toothed, shortsighted cliché from people’s worst nightmares in the 1940s, represents what exactly? Colonialism? Japanese imperialism? Who knows? So why present him that way? If there’s no target or no detectable underlying moral stance it just comes across as misanthropic.

The main character brings to mind WW2 perceptions of the Japanese. (BTW, whatever happened to Tasmania? Taswegians would be mightily offended.) Rating: Labyrinth: so-so Running Man: decent The Order to Stop Construction: my favourite segment - the high end of decent Overall: decent- Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Sep 21, 2019 1:28 am; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

I've booked tickets for four of the films in the Australian Centre for the Moving Image's Essential Anime:

Monday, 14 December - Boruto: Naruto the Movie; Thursday, 17 December - Princess Mononoke; Friday, 18 December - My Neighbour Totoro; and Saturday, 19 December - Laputa: Castle in the Sky. I've since learned I may have to stay late at work on Monday. Anyway, this week's review is the last of the Japanese Film Festival screenings, from last Sunday. I didn't fully grasp all the plot details so I've watched it again during the week at home. Ghost in the Shell: the New Movie Reason for watching: I've been following the Ghost in the Shell Franchise for a few years now so the opportunity to see the latest instalment at the cinema was most welcome.

Different decades, different directors, different faces: Major Motoko Kusanagi (L-R) 1995, 2015, 2004. Synopis: It's 2029 and, in the aftermath of world war, Japan has been booming thanks to it leadership in developing cybernetics. Things are beginning to stagnate, however, as older, established companies, in order to maintain market dominance, try to suppress innovation. At the same time Japan is trying to demilitarise by disbanding units and outsourcing security functions, leading to disatisfaction amongst the ranks, including the members of Major Motoko Kusanagi's former unit. When the Prime Minister of Japan is assassinated Kusanagi's team uncovers a web of connections between politics, profit seekers and disaffected soldiers. Things are complicated further by the Fire Starter virus that infects people’s ghosts, creates false memories and causes them to spontaneously rebel. The various strands all lead to a person who looks uncannily like the Major. Comments: For a franchise with a penchant for elaborate names, this movie sequel to the Arise story has the most prosaic title since the original movie way back in 1995. I suppose it reflects the straightforward way chief director Kazuchika Kise seeks to entertain us. While the cyberpunk themes remain and the plot has several entangled threads, the emphasis is on spectacular action, with three big set piece battles (a hostage crisis, a tank battle on a ship, and a two-part showdown with the Major's rivals from her former army unit) with police procedural (albeit clever) in between. The film doesn't dwell on the philosophising that hovers in the background, so beloved of Mamoru Oshii. Nor does it provide any startling plot twists, so beloved of Kenji Kamiyama. Oddly enough, despite the opportunities presented by the appearance of a doppelganger, the film doesn't use it to confound the viewer: there is never any doubt which is the real Kusanagi. More surprising, the film doesn't begin with the obligatory helicoper flight over the megapolis. That comes later. As does the the Major's signature freefall shooting of the bad guy through the skyscraper window before disappearing into the freeway network below. And there's also the expected cyberspace hacking graphically represented in three dimensional space.