Review

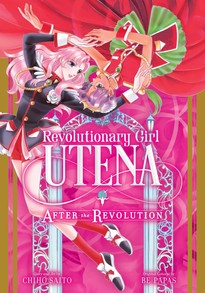

by Rose Bridges,Utena: After the Revolution GN

| Synopsis: |  |

||

20 years after Utena revolutionized and was subsequently erased from the world, the Student Council members have gone on with their lives, with no apparent memories of the duels or their parts in them. Touga and Saionji have become rival art dealers. Juri is a fencing champion and model, and Miki is a blueblood and world-renowned pianist. The desires and contradictions they struggled with throughout the course of Utena's journey are still deep within them, but the time for their own revolutions is fast at hand. Here are three stories of how Utena is able to lead her former classmates to smash their own shells while she searches for how to save Anthy. |

|||

| Review: | |||

Calling this version of Revolutionary Girl Utena "after the revolution" is a bit of a misnomer. In many ways, it makes the most sense if you pretend the ending of the anime (and the manga, although this particular series seems to build more on the anime's continuity) did not happen in the way we see it. Like the The Adolescence of Utena film and every other piece of Utena media out there, you can read it as a continuation, but it resonates more if you view it as an alternate re-telling. (Or better yet, just don't worry about how it relates to preexisting "canon" at all. Revolutionary Girl Utena as a franchise has never benefited from overly literal approaches to its constructions of reality.) It's just one where most of the main characters are now 20 years older than they were in the show, but without their memories of its events, they go on similar journeys to self-actualization. And everything is, once again, bathed in metaphor, symbolism, and allegory (allegorier, allegoriest). Despite this, Utena: After the Revolution is a work for preexisting fans of the series only. While it seems to have hit a reset on at least some of the characters' emotional journeys from the anime, it still builds on prior knowledge: There are little in-jokes that you won't get if you aren't familiar with the anime. More importantly, it also doesn't spend much time investing you in the characters. Utena: After the Revolution assumes that the brief introductory bios at the beginning of the manga are all you need to re-acclimate yourself. It's designed for those who are already deeply invested in this franchise—a group which absolutely includes myself—and particular in the supporting characters of the student council, and the idea of them forging their own revolution like Utena and Anthy. Essentially, each story is a bit like if each character (or characters, in the case of Touga and Saionji's story) were the protagonists of the show, the ones taking the last stand against Akio and in favor of changing their world. So I will approach this review assuming the reader is familiar with the original Revolutionary Girl Utena anime, referring to it without spoilers and occasionally making nods to the original manga and feature film continuities as well. So let's go through each of the individual vignettes. The first, and probably the strongest of the three, is Touga and Saionji's story. The two men are now rival art dealers, returning to Ohtori Academy in search of a famous painting called "The Revolution." Along the way, they're met with the now largely powerless ghost of Akio, who is guarding the painting and tries to ensnare them back into his control. But before he can do that, another shadow—a young Utena—encourages them instead to fight against him. What makes this story so fascinating is the push-pull between Touga and Saionji. They've seemingly grown apart even though they fight each other on the auction stage. In their own ways, they've resettled into the same relationship they had early in the show. Touga is the star with a new woman on his arm every night; Saionji is petulant and jealous. And yet as the story goes on, it becomes clearer that perhaps Touga should emulate Saionji rather than the other way around. Saionji is the one who truly appreciates the art they both deal in; Touga only sees it as a means for profit. Once again, Touga is more easily tempted by power—by Akio—but ultimately they'll need each other if they want to revolutionize the world. So yes, if you're like me: it doesn't explicitly ship them together, but the subtext, just like in the original anime, is strong. The way that art interpretation functions as a mirror to understandings of power and shifting expectations—including a painting literally changing in front of their eyes—is also meaningful, and helped me to better understand why these characters were in a career path that didn't seem like a logical way forward from where they were in the original storyline, unlike Juri and Miki. Every version of Revolutionary Girl Utena is about the ways we will only see what we want to see, until we're ready to face up to the biases society has imposed on us. Using visual art just makes the metaphor all the more apparent. And there's a gorgeous poetry to Touga and Saionji literally selling these illusions while also being trapped in them. The second story focuses on Juri, Shiori and Ruka in a future where Juri is a fencing champion and Shiori her manager. And of course it also deals, in its own way, with illusions and mistaking them for reality. There was something powerful for me about seeing Chiho Saitō explicitly confirm Juri's romantic feelings for Shiori. In Saito's original manga version of the story, Juri is seemingly heterosexual and in love with Touga, Shiori does not appear, and that version famously tends to play the queer themes closer to its chest (though they're not nonexistent, as is often misstated). Yet not only is Juri's love for another woman made clear here, but just like in all of her anime episodes, it's key to understanding her story. In this version, Juri is in a women's fencing championship where she learns that her opponent is not another woman but in fact, Ruka, her former school fencing team captain. As Juri is considering retiring from fencing, Shiori threatens to leave with Ruka and manage him instead, breaking Juri's heart; she can live without the sport, but not without the woman she loves. If Ruka in the anime seemed to exist to encourage Juri to move beyond her destructive love for Shiori, Ruka in this story represents Juri's fear of losing Shiori to a man—and that she can never truly be her "prince" because of her gender, or fundamental ordinariness. We finally get a glimpse of what led Juri to initially fall in love with Shiori, and the origin of her love of fencing. The story of how Ruka entered and exited their lives is also altered for this continuity. In the end, Ruka's presence turns out to be another illusion, only revealed after Utena shows Juri how to be a prince in her own way. Relevant to this discussion is the role Utena herself plays in all of these stories. Having moved beyond the reality of Ohtori Academy, she seems have taken the role of Prince Dios in the original story. Dios was always there to push Utena on in her moments of doubt—creating the miracle that Juri doubted would happen in her first duel with Utena, or giving her the strength to fight on in her second duel against Touga. Of course, what Utena attributed to Dios was also sometimes spurred by Anthy's feelings (particularly in the second of those examples)—that was part of the illusion that Utena created for herself—but he represented her belief in the ideal of a prince, and that she can become that ideal. Which eventually she does, if not in quite the way she expected in the beginning of the story. Having visions of Utena as an illusion to push the duelists further seems like a completion of that arc for her. Still, it turns out that she needs them as well, giving their revolutions value outside of better understanding themselves and freeing them from the societal biases imposed on them. Each duelist has to help push Utena toward her goal of rescuing Anthy. This brings us to the last of the stories, involving Miki and his relationship with his twin sister Kozue. This one was the overall weakest, and will likely be the most controversial since it goes further with the incestuous bond between the twins than previous versions of Utena have. There is a reason why Miki is generally the least popular of the original duelists, and usually the one people struggle the most to "figure out," especially regarding his relationship with his sister. While one can read it in the literal sense of two siblings having forbidden sexual feelings for each other, I've always seen the Miki/Kozue relationship as in the gothic-romance tradition of incest-as-metaphor: metaphor for what your sibling symbolizes to you. In the anime itself, it was the loss of their childhood bond and the desire to return to that idealized past together (Kozue's duel theme even references time machines), and here, it is mixed with the lack of desire Kozue has for her husband and for her traditional but unfulfilling marriage. In both, it's jumbled in with her jealousy toward Miki's success—in this case, through literally mimicking his actions in her sleep. The fact that Miki remarks that their relationship is still taking form like their music seems to open it up further to a multiplicity of interpretations about what specifically is going on between them. And what is Revolutionary Girl Utena if not all about that multiplicity, and about the multi-variant nature of relationships? It's their story that gives a child version of Utena the final push to reach a child version of Anthy. This last moment between the girls is another reason why it's hard to read the manga as a straight sequel, even if the other characters are older and tell us that 20 years have past. The dueling arena in Utena, where each character is transported in their final scenes, exists outside notions of linear time—and the story the manga tells follows suit. This may leave you frustrated on first reading if you're expecting these 30-something characters to have grown beyond who they were in the original story. Touga, Saionji, Juri, Miki and Kozue were all on the way to smashing their own respective eggshells by the end of the anime, especially in the case of the former three. But now, the erasure of their memories seems to have reset their personalities. All of their stories, but particularly those of Juri, Miki and Kozue seem like echoes of their arcs within the anime. If so, what was the point of everything that happened to them then—especially when in the final minutes of the anime, it seemed like they were still moving beyond their coffins even without Utena there to guide them? Yet at the end of the day, I can't find much fault with this volume other than the suspicious lack of Nanami. (She gets a brief moment in Touga and Saionji's volume, but I would have loved for her to have her own story, and I'm kind of puzzled as to why they left out such a popular character.) The way that time folds in on itself, and that these characters are simultaneously older and yet not changed at all from their teenage selves, is quintessentially Utena. It makes it a much more fitting 20th anniversary present than a straight sequel. This manga forces us all to go back into the headspace the original work put us in, and reexamine the ways in which we might not have changed as much as we think from when this series first took us for a ride. Society's strictures are very tempting. It's easy to want to take Akio's hand. Utena's way, the way to revolution and genuine satisfaction, is the hard way, and one we need to keep reminding ourselves of throughout our lives. Chiho Saitō's art is, as always, impressive. As someone who is less of a fan of the manga continuity but in love with her sumptuous visuals, it feels great to have a version of this that combines my favorite version of the story (the anime series) with her gorgeous, detailed art style. In the back of the manga, there's a short omake featuring discussions between Chiho Saitō and her editor about the idea of a 20th anniversary special, and the thinking that went into it. There's also a quote at the end by Kunihiko Ikuhara, director of the anime series and film, about the concepts he had for this 20th anniversary special. He describes the importance of loss, and the need to look backward as well as forward in building the future. That seems to be the central theme of the manga: the way that the duelists' pasts still impact them, and particularly the loss of people important to them (especially in the case of Juri and Miki's stories) have impacted their present-day relationships. They must grapple with those losses, and truly accept them as parts of their lives, in order to win their revolutions. The way the storyline has one foot in the past and one in the future (present?) is the perfect shape for this story. So if you go into this manga expecting an ideal happy ending for these characters, to see how they've blossomed into their true selves away from Akio's influence, that's not what you'll get from this. But if you're a true Utena fan, you're used to letting this world and story take you for a ride, and nothing being as you expected. You're used to divining the message of the story not from what literally happens but from all the colorful symbolism around it. If you go in with that open mind, this is a richly satisfying little anniversary present for all of us Utena superfans. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : A-

Story : B+

Art : A+

+ Gorgeous artwork, puts a fresh spin on the Utena mythos in a way that still resonates with the themes and characters we know and love, being more of an alternate retelling than a true sequel is quintessentially Utena |

|||

|

discuss this in the forum (8 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history |

|||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about |

||