House of 1000 Manga

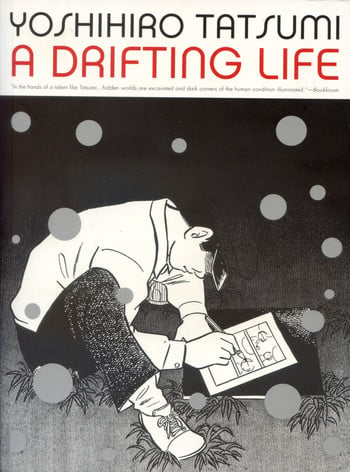

A Drifting Life

by Shaenon Garrity,

Yoshihiro Tatsumi passed away last month, bringing an end to one of the most remarkable careers in manga. Happily, he chronicled a sizeable chunk of it in his 2009 doorstopper of a manga memoir, A Drifting Life, which should be required reading for all who would dare call themselves otaku. A Drifting Life scored major critical attention on its release, winning the Tezuka Cultural Prize in Japan and two Eisner Awards in the U.S., for Best Edition of International Material (Asia) and Best Reality-Based Work. (I've griped about this before, but people, why can't the Eisners just call it Best Nonfiction? The tiny bat-winged copyeditor that sits on my shoulder bursts into flames every time I see that.) If you've ever wondered where manga came from, this manga is the best place to start getting answers.

Tatsumi uses the real names and faces of people in the manga industry but adopts pseudonyms for himself and his family members, even though A Drifting Life is obviously autobiography. His whey-faced stand-in's name is Hiroshi, although in the early chapters he (or maybe the translator, American alt-comics great Adrian Tomine) sometimes forgets to stay in the third person: “I burned through the entire Nakamura Manga Series of works by Noboru Ooshiro, Takashi Shiga, and Bontaro Shaka. My heart beat with excitement as I read the adventure novels of Juzo Unno and Yoichoro Minami.”

As the manga opens, Hiroshi is in junior high. It's the late 1940s, Japan is still struggling out of the ashes of World War II, and comics provide a much-needed escape for Hiroshi and his sickly older brother Okimasa. The brothers enter manga-drawing contests in children's magazines, eventually making enough from the small cash prizes to supplement the family income and inspire fantasies of a career in manga. At first Okimasa is the more talented of the two, but his health problems grow more serious, and as his future becomes doubtful he envies Hiroshi's bright prospects.

Manga is still a small, cozy world. Hiroshi is able to strike up a correspondence with Noboru Ooshiro, the greatest pre-Tezuka manga artist, whose charming full-color children's comics rank among the best of Japan's wartime literature. Ooshiro even invites Hiroshi to join his studio, but Hiroshi, then a teenager, is a little too in awe of the master to accept. He's even more thrilled by an audience with Osamu Tezuka, then still a med student living with his mother.

These early chapters about the birth of the manga industry are the most entertaining part of A Drifting Life, simply because the subject matter is so much fun. Even the legends in the field are barely more than kids themselves, and a youthful enthusiasm permeates everything. Hiroshi tries his hand at whatever the comics business has to offer, from posing as a housewife to win a competition judged by Sazae-san creator Machiko Hasegawa to starting his own publishing circle for teens, the Children's Manga Association. His urge to form groups, to organize and quantify the nebulous new art form, will be a defining feature of his adult career.

When Hiroshi skips college to become a professional cartoonist, some—but not all—of his naïve optimism gets chipped off. A lot of the publishers he worshipped as a kid turn out to be fly-by-night outfits run out of dingy storefronts and cramped apartments. After some hustling, Hiroshi becomes one of the talents pimped by a seedy outfit that dodges debt collectors and routinely runs out of money to pay its artists. What the hell; he's happy to be in the business.

If you're a hardcore manga fan, part of the fun of A Drifting Life is seeing classic manga-ka as youngsters just starting out. No lie, I got a chill up my spine when future Golgo 13 creator Takao Saito first looks into a Mickey Spillane novel. The publishers can't predict what will sell, initially putting their money in newspaper-style gag manga without realizing that Tezuka and his sprawling adventure sagas are the way of the future. (Nowadays, things have arguably come full circle, with gag manga magazines taking a healthy chunk of the market in Japan.) In the background, Tatsumi shows postwar Japan regenerating into the pop-culture beast that would someday conquer the world, moving from kamishibai to radio to television to Godzilla movies. It seems manga, like Japan itself, could grow up to be anything.

The question of what manga will become dominates the second, more talky half of A Drifting Life. After establishing a successful career in children's adventure manga, Hiroshi becomes dissatisfied, searching for new visual approaches and ways to tell more adult, filmic stories. Of all the things he accomplished in his manga career, Yoshihiro Tatsumi is most famous for coining the term gekiga (dramatic pictures) for challenging, mature manga. At the time he invented the term, it mostly referred to hard-boiled crime stories, material considerably pulpier than what most modern readers would consider a serious graphic novel. But the work of Tatsumi and his colleagues pushed the boundaries of what manga could be.

The question of what manga will become dominates the second, more talky half of A Drifting Life. After establishing a successful career in children's adventure manga, Hiroshi becomes dissatisfied, searching for new visual approaches and ways to tell more adult, filmic stories. Of all the things he accomplished in his manga career, Yoshihiro Tatsumi is most famous for coining the term gekiga (dramatic pictures) for challenging, mature manga. At the time he invented the term, it mostly referred to hard-boiled crime stories, material considerably pulpier than what most modern readers would consider a serious graphic novel. But the work of Tatsumi and his colleagues pushed the boundaries of what manga could be.

Not that they were alone. A Drifting Life spends an inordinate amount of time on theoretical debates between rival schools of experimental manga: should they call it komanga? How about sestuga? What does any of it signify, anyway? In his efforts to define gekiga, Hiroshi works on two edgy manga magazines, Shadow and Skyscraper, and pens Tatsumi's crime classic Black Blizzard. Eventually, publishing houses take sides and fight over talent.

Beyond a point—say, around page 700—it takes a certain obsessive fascination with manga as an art form to maintain interest in all these late-night debates in sweatbox studios and izakaya. Although A Drifting Life follows the personal lives of its key players, it's first and foremost about manga, manga, manga. Hiroshi's friendships are all with manga artists (and a friendly telegram man who delivers missives from his editors), and his sexual experiences are fleeting, confusing, and unsatisfying: an afternoon with a nude art model, a partly consummated affair with the landlady at an artists’ apartment, virginal brushes with infatuated high-school girls. Warning to all would-be manga-ka: whatever Bakuman. may tell you, manga is not a good way to get laid.

Being a true Otaking, of course, I adore every page of A Drifting Life. In all his manga, Tatsumi is a blunt and relentlessly honest storyteller. That an artist of his caliber and sensibilities was able to leave behind a first-hand account of the early years of manga, captured forever in ink, is almost too good to be true. A Drifting Life sometimes rambles and gets caught up in minutiae, but Tatsumi remembers so much, and recounts it so vividly, that it's worth lingering on. And it's fun; even the lowest moments in Hiroshi's life glow with his enthusiasm and love of the craft. Tatsumi's works of fiction are famously bleak, but his autobiography is a happy work, filled with equal parts hope and nostalgia.

A Drifting Life ends abruptly in 1960 with two historic events: the first youth protests against America's use of Okinawa as its launching point for the Vietnam War, and the publication of Sanpei Shirato's manga Tales of the Ninja. These events presage the most important phase of Yoshihiro Tatsumi's career. Inspired by the political upheavals of the Sixties and a new wave of dark, gritty manga from young creators, Tatsumi would become the greatest gekiga artist, the exemplar of the genre he named. In the 1960s and 1970s he would draw the grim, quiet stories of contemporary urban life collected in English in the Drawn and Quarterly anthologies The Push Man, Good-Bye, and Fallen Words. (I would be remiss to omit the earlier Tatsumi collection Good-Bye and Other Stories, published by Catalan Communications in 1988 and for many years passed reverently among American manga fans who had no other access to Tatsumi's work.) He became one of the core contributors to the legendary alternative manga magazine Garo, as did Shirato, whose Legend of Kamui had such an impact on Japanese counterculture that college protestors used to chant, “We are Kamui!” From 1960 onward, Tatsumi was one of the artists who made manga grow up.

Tatsumi doesn't let us see any of that, but by the end of A Drifting Life the seeds have been planted. Perhaps all of it, Good-Bye and The Push Man and the Tezuka Cultural Award, is inevitable from the first pages, from that teenage boy drawing feverishly into the night. It's there when the young Hiroshi stares at fireflies on a summer night and aches to draw, and when Tatsumi writes in sincerity, “Never before had Hiroshi felt so much love for manga. He felt deeply moved that he was fortunate enough to draw manga.”

discuss this in the forum (2 posts) |