Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Bringing Home The Sushi

by Jason Thompson,

Episode XCVIII: Bringing Home the Sushi

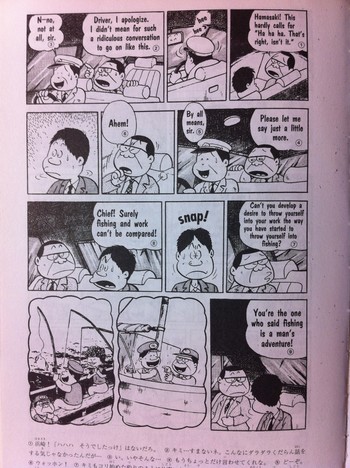

"Can't you develop a desire to throw yourself into your work the way you have started to throw yourself into fishing?"

"Chief! Surely fishing and work can't be compared! You're the one who said fishing is a man's adventure!!"

—Juzo Yamasaki & Kenichi Kitami, Diary of a Fishing Freak

It's too bad more people don't study countries through their pop culture. Maybe teachers think it's not academic enough. Maybe they say it's just a partial picture of a country (but a partial picture is better than no picture). Or maybe it's just something people do with some countries and not others. For instance, there's no books called An Inside Look at Chinese Military History Through Wuxia Films, or An Inside Look at Korean Society Through K-Dramas, or An Inside Look At the Arab Spring Through Egyptian Ramadan TV Serials. But there IS Bringing Home the Sushi: An Inside Look at Japanese Business Through Business Comics, a standalone book published in 1995.

This book with the long title, which I got for 99 cents on alibris, was published by the creators of Mangajin magazine, which is also pretty interesting. From 1990 to 1997, for 70 issues, Mangajin, subtitled "Japanese Pop Culture and Language Learning," was packed like a bento box with articles about geisha, bullet trains and politeness levels, mixed with letters from readers in Japan joking about how they'd mixed up the word basu with busu. But not only that, Mangajin also included manga, in the original right to left format, with the text translated in the margins instead of in the balloons so you could compare the English and the Japanese!

Manga…Japanese pop culture info…unretouched art and translations so literal they're hard to read…they were 20 years ahead of their time, right? But the difference between Mangajin and the many "learn Japanese through manga" things available today is that it wasn't aimed at otaku; instead, it was aimed at people who may never have watched an anime in their life but wanted to learn about Japan's booming late-'80s, early '90s economy. Mangajin printed Japanese comics mostly as a fun way to introduce the reader to colloquial Japanese. But Mangajin had one advantage over trying to teach English to Japanese businesspeople from Superman (or teaching Japanese business culture from Bleach): the existence of JAPANESE BUSINESS COMICS!! Although Mangajin articles occasionally mentioned shojo and shonen manga, the focus was on adult manga—josei, seinen—and especially manga about the glamorous world of salarymen, office ladies, big business and binge drinking. While otaku were, as always, enamored with escapist stories about ninja and witches and science fiction, and less enamored with stories about pensions and workplace sexism, Mangajin was happily printing hardcore manga about Japanese business culture, the kind that never sells in the US…except maybe (?) for one teeny-tiny period when American businesspeople thought that by reading manga they could make lots of ¥¥¥.

Unfortunately for anyone who hoped Mangajin could travel into the future and do a license rescue of Mari Okazaki's Suppli, the truth is they never published complete storylines; they only published random segments of business manga, rarely more than a chapter or two. But they did do one sort-of graphic novel, Bringing Home the Sushi, a collection of nine stories by different artists. Bringing Home the Sushi is aimed at a more general audience than Mangajin; for one thing, the dialogue is actually translated in the word balloons instead of outside it. (Other formatting experiments didn't work out so well: the art isn't flipped, but the book is printed Western-style, so you read each page R->L and then turn to the next page L->R, which makes my head hurt.) Between stories are essays by various Japan experts, to help explain the context; and each story sheds a different light on the world of Japanese salarymen. Reading all these stories together is like nibbling at a bunch of izakaya food, not eating a full meal…but it's delicious.

As Tomofusa Kure explains in his opening essay, this book is basically a battle between two different kinds of salarymen. "Good" salarymen are the kind that work hard to succeed, the adult versions of Shonen Jump heroes who fight with contracts and presentations instead of chakra and shuriken. The first type of salaryman is represented by Kenshi Hirokane's Section Chief Division Chief Manager Executive Director President Kosaku Shima, the ultimate salaryman hero. Shima is the James Bond of salarymen, a great boss and a great employee who always wins AND always does the right thing, and who, in true Horatio Alger style, gets promoted up and up and up until he's the president of a massive electronics company. In the other corner, you have manga about "bad" salaryman, the slackers, the goof-offs, who never get promoted. This includes truly bad employees like the scheming goof-off in Hiroshi Tanaka's Nakana! Tanaka-kun ("Don't Cry, Tanaka-kun!"), but it also includes characters like Hamasaki from Tsuri Baka Nisshi ("Diary of a Fishing Fool"), or perhaps the main character in Cooking Papa, who are actually good-hearted and reliable but simply care more about their family and hobbies than about advancement at work. (Of course, Kosaku Shima cares about his family too; the manga's reality is just warped so that he's able to care about his family while also continually advancing in the company.) Kosaku Shima has been running in Morning magazine since 1983; Tsuri Baka Nisshi has been running in rival Big Comic Original since 1979. Together they represent the two ideals of how to be a 'proper' salaryman; you can do the oldschool guts-and-determination thing and struggle to get that raise and get that promotion, or if you don't have what it takes (loser), you can take consolation in knowing that you love your family and you're a good cook or a damn fine hobby fisherman. Or perhaps my personal favorite, you can be the biggest nerd in the office.

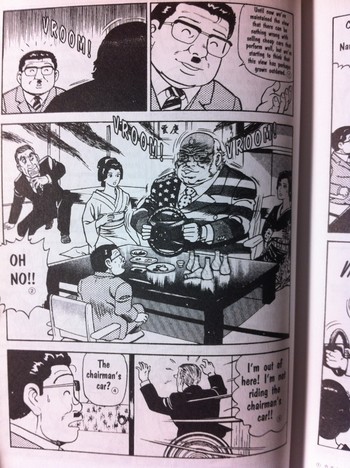

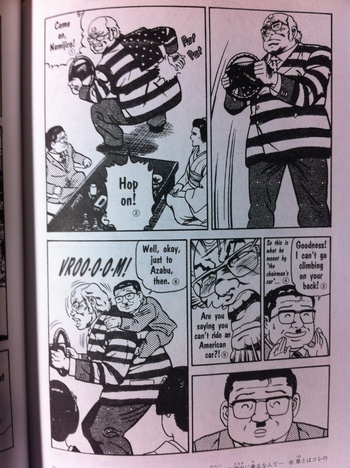

Almost all the manga in Bringing Home the Sushi fits into one or both of these categories: the earnest struggle-to-succeed story or the Dilbert-style slacker comedy. (Maybe more Blondie than Dilbert.) It will delight any shonen fan to discover that the earnest stories are totally insane. Torishimariyaku Hira Namijiro ("Director Hira Namijiro") by Tatsuo Nitta, is, like his other translated manga, The Quiet Don, the story of a quiet little wimpy-looking guy who turns out to be a complete badass. In the short scene in the book, Director Namajiro, who works at a Japanese auto firm, is forced to entertain an American automobile executive, Chairman Icepocca, at a drinking party. Of course, Icepocca is a giant, blustering behemoth, and he gets so drunk he decides to play car with Namajiro riding on his back, smashing him into the walls as he corners ("A ha ha ha ha! It accelerates! It corners! It stops! The basics of performance are all right there in American cars!") Of course, by the typical shonen manga combination of (1) enduring extreme physical pain and (2) being honest and courageous even when in reality he'd get in big trouble for doing so, Namajiro eventually wins the respect of the American, and we, the readers, get the awesomest portrayal of an American businessman in a manga ever.

"Humoring the drunken client" is apparently a staple of Japanese business and business comics; even in Tsuri Baka Nisshi, the hero meets a big client who's also a fishing nut and whose favorite amusement is to watch geisha pretend to be fish and fishermen and chase one another around the room singing a song. But this is just the merest of a salaryman's challenges. In the sample of Section Chief Kosaku Shima, Shima has been transferred to a remote branch factory that makes breadmakers, but on his first day he unthinkingly says the bread isn't very good, and all the employees give him the cold shoulder. Shima's solution is to eat bread continually until he learns to appreciate what his employees go through. ("From now on, I'm going to eat bread for lunch every day. Even if I never learn to like it, I'm going to keep eating it until I know the difference between good bread and bad bread! I've never been this intensely focused on anything before!") Meanwhile, way below Shima at the very bottom of the corporate ladder, Yosuke, the hero of Jiro Gyu and Yosuke Kondo's Eigyo Tenteko Nisshi ("Notes from the Frantic World of Sales"), is having his first day on the job. Yosuke, a wimpy appliance salesman, is really freaked out as his bosses line up all the new employees and tell them to shut up, go out there and SELL, SELL, SELL!! "This place is a battlefield!" he thinks, sweating. Eigyo Tenteko Nisshi has the feel of a "struggle to succeed" shonen-style story, but at least it doesn't make it look easy. Yosuke's group leader, Shibata, tells him "I'll take such good care of you that you'll bleed from your butthole!"

The Japanese business world is traditionally a sausage fest. Even into the '80s and '90s, most Japanese working women were expected to be little more than secretaries, "office ladies" who did photocopies and faxes, got tea for the men, and were expected to leave the office when they got married. (From the essay in Bringing Home the Sushi: "Some Japanese corporations even nudge their young OLs into marriage by offering classes in sewing, cooking, flower arrangement, and other skills that will make them more attractive marriage prospects.") OL Shinkaron ("Evolution of the Office Lady") by Risu Akizuki, the only female creator in the book, is a sort of Cathy-style four-panel comic about those silly office ladies and their wacky misadventures (buying clothing, flirting with guys, etc.), which has been running in Japan since 1989. Akizuki does write about sexual harassment, and some of the strips are actually quite funny, but the institutionalized sexism feels like stepping back into the world of Mad Men(a world, admittedly, only 20 years before some of these strips). Kazuyoshi Torii's Toppu wa Ore da!, about a guy who works for a kick-ass female section chief and wants to be as good as she is, is more of a feel-good story about conquering sexism, but still, the heroine can't be shy about flirting to win over a client. ("Well now, that's really something! A female section chief, and a beauty to boot!") Bringing Home the Sushi came out 15 years ago, so maybe it's just a little out of date, but there's no manga in this book quite like Moyoco Anno's Hataraki Man, which tells the story of a female professional from a female perspective.

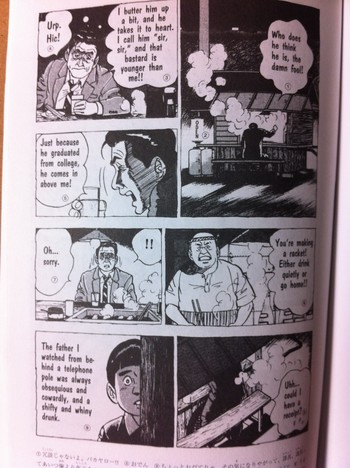

This book is a great sampler of manga that most companies would never dare translate. (Although a few volumes of OL Shinkaron and Kosaku Shima were translated in Kodansha Bilingual editions.) Also, it accomplishes the impressive feat of humanizing Japanese office workers, a group often unfairly portrayed in the American media as "antlike automatons" (to quote Laura Silverman's opening essay) and in shonen and shojo manga as "the main characters' boring parents." One of the only complete stories in the book, Ningen Kosaten ("Human Crossroads"), is a short story about the troubled relationship between an ex-salaryman father and his salaryman son, who remembers an incident from his childhood when his father pretended to have been mugged to cover up spending his entire paycheck on booze. Now, the son is getting older, and he's worried that he's turning into a loser like his dad.

If that sounds too serious and emo, don't worry: this book also has plenty of drunk businessmen wearing American flag suits, and junior sales executives spazzing out, and businessmen eating all the bread they can. This book has almost every mood and type of comic; the only real problem is that it's too short. I read Bringing Home the Sushi when I first started working at Viz, and it actually did help me in business. "From now on," I thought, "I'm going to read manga every day. I'm going to keep reading it until I know the difference between good manga and bad manga! I've never been this intensely focused on anything before!"

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (18 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history