Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga Special: Salaryman Kintaro and Quiet Don

by Jason Thompson,

House of 1000 Manga Special Travel Edition Part I

I'm out of the country this week on a trip to Jordan, which is currently experiencing pro-democracy protests not yet as big or as violently suppressed as the ones in Egypt. I thought I might segue this into something Jordan-related, but I don't know any manga set in the region that's as good as Joe Sacco's graphic novel Palestine. (The lame ending of Tezuka's Adolph doesn't count.) If the king stays in power, as it's looking like he will, my question is, for better or worse, where will I get my manga? Amman isn't exactly crawling with BookOffs and Kinokuniyas. I could bring some books on the plane, but extra baggage is expensive.

Luckily, technology comes to the rescue. I don't own a Kindle or an iPad (sorry, Viz and Yen Press apps), but I own an iPhone. Furthermore, my wife develops iPhone apps, so between the two of us, we form a small Venn diagram of iPhone manga-reading technology. And while I've written elsewhere about the sordid, seedy world of bootleg manga apps, I don't want to be caught illegally reading manga and renditioned by the Jordanian Secret Service. Those dudes are bad news.

So join me as I settle into this airplane seat for this 10-hour flight and read some manga the easiest way I can while traveling: on my phone. I used to be skeptical about cellphone manga. I prefer manga that can be physically acquired, read in the bath, and swum around in, the same reason that Uncle Scrooge prefers coins in his money bin. But I also like the idea of being able to hold all my manga within reach of my arms, carrying it around with me all the time, absorbed in my brain…so these two impulses are contradictory. Digital manga, although not satisfying in the primitive way a physical object is satisfying, allows me the temptation of having whatever manga I want, wherever I am..., whenever I want it.

Another advantage of digital manga (I mean actual digital manga, not the company 'Digital Manga') is, it's cheaper to make, and this means you could publish weird stuff that would never have a chance of selling in America. No matter how low American manga companies slash their lettering rates and translation rates, physically printing a few thousand or ten thousand graphic novels costs anywhere from $10,000 on up, just for labor, ink and paper. But with digital manga, all you have to do is pay for the rights, and then you have it translated for dirt-cheap by some Japanese major desperate to get into the manga/anime industry, and presto! The printer's loss is the reader's gain as licensed digital manga, like certain other shameless ways of digitally distributing manga, provides an opportunity to read stuff that'd never be translated otherwise.

Assuming anyone is crazy enough to publish it, that is, which leads me to NTT Solmare. This Japanese company is one of the bigger legit companies doing manga on the iPhone store, and I've already reviewed some of their other books, such as Buichi Terasawa's Cobra. They've published some manga so odd that there's no way it would ever get on the shelf of a Borders in America, unless homeless manga fans are squatting in an abandoned bookstore. Curiously, they also have cell phone versions of some manga translated by other publishers: Mayu Shinjo's Ai Ore (under the original literal title "Instead of Singing Love Songs, Drown in Me!"), published by VIZ, and Kaoru Tada's Itazura na Kiss, published by DMP. I've got to assume that there is some sneaky rights thing going on that VIZ and DMP have no control over, much like how Square Enix's online manga store has online versions of the same translations VIZ and Yen Press paid money for. But given the choice, it's still easier to read those books in print, so I haven't been downloading Ai Ore volumes off of iTunes.

One of the types of manga published by NTT Solmare is seinen ("men's") manga. The word seinen refers to any manga published in a "men's" magazine, from Maison Ikkoku to Battle Angel Alita to Steel Ball Run to Hataraki Man,but NTT Solmare is publishing some of the most hardcore stuff, manga so manly it'll make you want to ride cycles all night with your pals in your tattered school uniform, go fishing at dawn on the open sea, chug some beers with yakuza for lunch, and finish the day by singlehandedly carrying a 620-pound, 8-foot long wooden penis down the main street of Nagoya for the Hounen Matsuri. Salaryman Kintaro and The Quiet Don are two of the most oldschool manly manga I can think of, and even though Salaryman Kintaro started in 1994, they epitomize the '80s, a time when machismo and salaryman work ethic dominated manga, the time of the Japanese economic boom. Reading these manga is kind of like stepping into the world of Mad Men, only without the clever dialogue and self-referential commentary on sexism and racism. This is the pure stuff, the kind of thing that you'd find at used bookstores in Japan, which makes it especially bizarre to see it translated on cellphones. (Though actually, many Japanese digital manga sites, like Sokuyomi, specialize in selling out-of-print manga online.) Both were super-hits in their time, adapted into TV series and movies, and now they're available in English.

Hiroshi Motomiya's Salaryman Kintaro is about a former gang boss who becomes a salaryman. After his wife dies leaving him with his infant son, Kintaro Yajima , ex-leader of the 10,000-strong Hasshu Rengo biker gang, abandons the thug life and goes to Tokyo to work for a corporation. His new coworkers in their suits and ties are bewildered to see him show up for work surrounded by his ex-gangbangers bidding him farewell, but Kintaro has an "in": he was given his position by Yamato Morinosuke, the venerable chairman of the company. Yamato met Kintaro while he was out fishing, and he owes him a favor; onetime fisherman Kintaro (fishing is a super-macho profession in Japan) saved him by swimming seven straight hours when his boat broke down leaving him adrift at sea. Honorable old Yamato, in fact, is getting tired of the salaryman life and starting to question what it all means. "What is the salary man? Since when did the bachelor degree become a must for them? Since when they were chosen to wear suits?" The sinister, puffy-faced president Oshima, who is angling for control of the company when the old man retires, doesn't have any such self-reflection. Like the bad yakuza in a yakuza film, Oshima has no honor; he's one of the new corrupt breed who just cares about money.

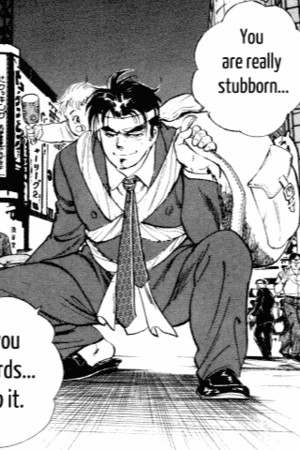

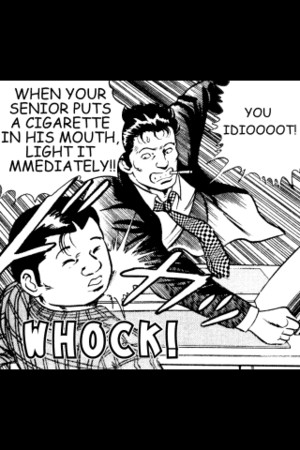

Only one man stands in the way of his control of Yamato Construction, and of course, it's Kintaro. With his headband, his long tie floating in the wind, and his infant son strapped to his back, he's like a salaryman Lone Wolf and Cub. Since he is a high school dropout and has no office skills in the traditional sense, Kintaro is first put to work making photocopies and sharpening pencils. His artisanal pencil-sharpening technique, an art practiced in the West only by David Rees is so incredible that it soon attracts the attention of everyone in the office. ("Delicate, refined and indeed comfortable to use. It's the sincere way of sharpening!") Soon, he makes friends with all the staff and joins them for sake, karaoke and mahjong. ("It can be said that real training for salary men is in the night!") This being a Japanese office in a 1994 manga, the female characters are all secretaries and office ladies, who all have a crush on Kintaro. It's just a question of whether they know it yet. But Kintaro also rubs some people the wrong way. "He's not a human being but a stray dog!" snarls the loathsome Oshima. Managing Director Kurokawa, a cold corporate oligarch who gives Kintaro a lecture, turns out to be just as badass as our hero in his Lawful Evil way ("Human beings cannot live alone. There is a high-and-low relationship in the human society!") Eventually Kintaro cuts his hair and starts looking more like a regular salarymen, but he's always a glowing, nigh-radioactive mass of testosterone deep down. When yakuza or random jerks harass his coworkers on the street, he sticks up for them by sticking his foot up the bullies' asses. "Don't make a fool of Salary Man, you idiot!" he shouts. (That's how it's translated, anyway.) Kintaro may not know about business, but he's a Man's Man and a raging fighter. The moral of this manga is BUSINESS SENSE DOESN'T MATTER AS MUCH AS BEING A MAN AND KICKING ASS! His coworkers, too, turn out to know karate and judo from their school days, reclaiming their submerged manliness in Kintaro's presence.

Salaryman Kintaro reminds me of Tooru Fujisawa's GTO, another manga in which a loose cannon ends up working for the Man and reforming/reinforcing society's rules in his crazy, wacky way. Unfortunately, though, Kintaro doesn't have GTO's fanservice or sense of humor. Kintaro never falters; his homespun, two-fisted gangbanger wisdom is the cure for every problem, whether it's a mahjong game with his coworkers (solution: an awesome yakuman win), fishing with his boss, or teaching a lesson to a salaryman's spoiled son (solution: punch him in the face). If there's any sense of irony in this corporate fairytale, it's buried deeper than even my radar can detect. It's pure '80s nostalgia and manly adventure for people who are reaching the "too old to read manga" age.

The Quiet Don, on the other hand, is like those parts of GTO when Onizuki is humiliated in public, wears an elephant's trunk on his penis, and walks around with a pizza box full of human poop. Started in 1988 and somehow still running at 96 volumes, this manga is almost the opposite of Salaryman Kintaro: a badass yakuza who's a meek, lovable salaryman inside. Although maybe inside that he's a badass yakuza again…it's kind of infinitely recursive. Kondo, an approximately three-foot-tall, wimpy-looking man whose job is designing ladies' underwear, is the son of the boss of the Shinsen-gumi yakuza clan. When his father is murdered, Kondo must step up and become the boss of hundreds of tough, mean, scarred yakuza. He doesn't want to do it, but his mother, a yakuza queen with goddess-like authority, insists. "My son is a natural born gangster. He's afraid his ferocious yakuza blood would start to flow through his body. That's why he insists on doing office work." Kondo gets permission from his mom to continue designing lingerie that the same time that he manages the affairs of the yakuza, and there you have the setup.

The point of reading The Quiet Don, apart from its absurdity, is waiting for Kondo to snap. And really, you have to wait and wait and wait. At his job at the lingerie company, he's a passive pud, bullied by his coworkers and angrily defended only by his female coworker AKINO. ("Get angry, Kondo-kun! You are the flabbiest and quietest man in this company. That's why they take advantage of you! Don't you have any pride as a man?") No, he doesn't. His obnoxious, bald boss asks him to run around Ginza wearing nothing but panties as a "kamikaze PR" stunt. ("You will be a running billboard. Media will probably condemn us but it's a great way of promotion.") Meanwhile, when his yakuza homies ask him for permission to avenge the murder of his father, he says no, over the objections of angry sub-boss Hijikata. ("They blab around that Shinsen-Gumi is chicken-hearted! We've become a laughingstock in this business!") Kondo abhors violence; his solution is to go over to the headquarters of the enemy yakuza by himself on his day off and politely ask them to disband. Of course, this works, but sadly, not for any particularly clever reason. "I'm afraid of being absorbed in the world of gangsters," he confesses. But his mother knows he's really got the makings of an amazing yakuza deep down…right?

Unlike the dead-serious Kintaro, The Quiet Don is basically a gag manga. There is lots of really crude, sleazy humor and some (censored) nudity, both male and female. Kondo is continually designing awful, disgusting undergarments, such as ultra-absorbent "napkin briefs" ("Practical because of the high absorption, it solves the women's problem of vaginal discharge"). Perhaps it's just because everybody in this manga is a loser that the sexism level seems higher than Kintaro; the female characters are all pathetic losers just like the men. Or perhaps it's just extra sexist. In one subplot his scheming subordinates try to marry their daughters off to him. ("Sayaka-chan, what kind of underwear are you wearing now? I'm just interested in girls' underwear.") The art is less polished than Kintaro, and the character designs are strange; some of them seem to be based on the photorealism of Ryōichi Ikegami, but they're mixed with gag manga characters, like Kondo. But when our hero slicks his hair back and puts on his dark glasses, watch out! His coworkers at "Pretty KK" lingerie company don't recognize him as that loser they see every day in the office, and they're left marveling at that mysterious, studly, Hobbit-sized yakuza.

The Quiet Don and Salaryman Kintaro are both fantasies for male office workers; like Superman, the tired corporate drone imagining that they are a badass bosozoku inside. The Quiet Don is much more of a humor manga than Kintaro, though, and I found myself wanting to read more of it, if simply to wonder where they were going to take this inane concept, whereas with Kintaro they dish out the same recipe of manly soup in every chapter. Beneath Kintaro's polish, it's extremely predictable and has as little relation to reality as The Quiet Don does. They're both interesting manga to read as artifacts of oldschool Japanese pop culture, but not so much for their own sake.

So if someone loaned me All One jillion volumes of The Quiet Don and Salaryman Kintaro, would I read them? Well, I'd skim them, but I'd be more inclined to do so if they weren't on a smartphone, or rather, if the smartphone versions were done differently. There are a couple of problems with the format. Like most digital manga for devices with small screens, including the cellphone manga by Tokyopop and GoComics (but not Comixology and the various pirate apps), the manga are chopped up so that you read them panel by panel. I have always hated and will always hate this format. It may work pretty well for four-panel manga, but for story manga, it wrecks the original page layouts and artwork and slows down the reading experience. In NTT Solmare's apps, you can either let tap the pages to go to the next one, or let the manga play at its own speed. The 'play at its own speed' is, unfortunately, frustratingly slow, and YOU can't entirely disable it, since whenever there's a transition animation or pan effect, you have to sit through it at its glacial pace. I really wish publishers who digitize manga wouldn't screw with it like this; they'd save themselves a lot of time cutting and pasting images, the manga would be more faithful to its original format, and frankly, most manga isn't very text-dense, so there's plenty of manga where I can read a full page just fine on a tiny screen. It's certainly far more invasive and art-altering than flipping the art left to right (which these apps don't do).

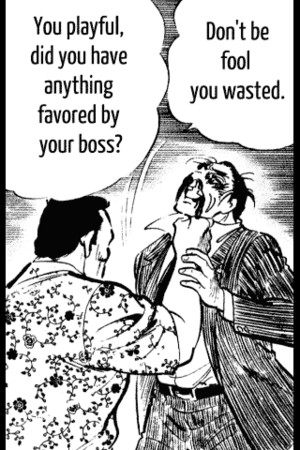

Another problem is bad translations, a necessary evil on the economic road to Making the Cheapest Manga Ever. "Don't be fool you wasted. You playful, did you have anything favored by your boss?" a thug threatens a businessman in Kintaro. Or another example: "Hellooo! I am... single man, Ichiro Maeda!" Or: "If it were the salary man who makes room at the elevator to let you feel pleasant, then race called 'salary man' would be a group of SHIT!" (capitals in the original) I could do a hundred other examples, but it goes behind the point of unintentional hilarity pretty soon and becomes simply tedious and unprofessional. Here's a suggestion for the publisher: don't have your manga translated on the fly by the person scanning them.

Finally, another problem, especially for macho manga like these, is that the iPhone manga is censored. The censorship (mostly in The Quiet Don) is handled by just cropping out whatever's offensive, so that in some panels people's bodies, or even their faces, are cut off in interesting ways. The censorship must have been NTT Solmare's decision, but Apple's iTunes Store is also known for their censorship and harsh age ratings; for example, according to the iPhone, any app which lets you access the web is rated 17+. When Kodansha Japan submitted all their manga as individual apps, a vast number were rejected outright for content reasons. It's possible to get around this by making a single "comics" app and then downloading new manga as in-app purchases online, but it's still inconvenient. (In contrast, most cellphone manga in Japan is available on networks that don't have such strict requirements, and some of the bestselling cellphone manga in Japan is said to be yaoi, the kind of thing you don't want people to see you buying in a bookstore.)

Last but not least, Salaryman Kintaro and The Quiet Don are both sold for $2.99 per segment, with each segment containing three chapters. Assuming about ten chapters per book, that's the same price as printed manga. Is it worth it? I'm not going to answer that. I'm just going to answer that it's nice to have a bunch of manga on my phone…but there's a lot of ways it could be done better. But while I'm in Jordan, that's the best I can do, so be here next week as I continue my tour of digital manga.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (3 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history