The Mike Toole Show

Tatsunoko Time

by Michael Toole,

The floodgates are open. I've known just a bit more about the recently-emerged Anime Sols and Daisuki streaming sites than the general public for some time now, so it's been nice to have not one but two cats let out of the bag in recent weeks. Not surprisingly, both Anime Sols and Daisuki are of particular interest to me, a weird old guy who likes weird old cartoons and frequently bemoans the fact that, despite our amazing modern world, I still don't have an option when it comes to parking my butt on the couch and watching episode after episode of Gordian Warrior. Thanks to new services like this-- and in particular Anime Sols, who have a sweetheart deal with Studio Tatsunoko-- my dreams of indolence and very old cartoons might soon become reality.

In the meantime, I've been downing episode after episode of Yatterman. Heard of it? You might have-- it got a nifty-looking but oddly dull live action film adaptation a couple of years back, directed by no less than Japanese cinema icon Takeshi Miike. That film came on the heels of a sparkly TV remake of the original 1970s show, which is also available on Anime Sols for people fortunate enough to be in the US and Canada. Yatterman, which I'll talk about in some detail later, is one big fat spoke in an entire wheel of global hits from Tatsunoko. We've heard of some of ‘em-- like Speed Racer, and Gatchaman, and Robotech - but there are plenty we've haven't. I'm gonna talk about both categories.

It wasn't just the 3-hour Yatterman marathon that got me thinking hard about Tatsunoko-- it was poring over their list of works. The company was founded in 1962, by three brothers: Tatsuo, Kenji, and Toyoharu Yoshida. Like the similarly emerging Tele-Cartoon Japan, these three brothers decided to pursue mainly television animation, which was starting to explode across Japan as families bought up TVs like hotcakes. This new company, dubbed Tatsunoko (the term means “seahorse,” but it can also be translated as “Tatsu's baby,” because the company was presided over by the eldest Yoshida, Tatsuo!), took a year to develop their first big project-- an ambitious kids’ science fiction series called Space Ace. Recognizing that the series was a tall order for the fledgling company, the Yoshidas teamed up with Toei to get the show off the ground. But Toei wanted a piece of the copyright pie-- they didn't just want to work on Space Ace as contractors, but wanted some ownership rights as well. Tatsunoko balked at this, and production was scrapped. Toei went ahead with a space adventure TV show of their own, Space Patrol Hopper, but Tatsunoko still benefited-- animator Hiroshi Sasagawa had spent time during the planning phase training at Toei's animation studios, and was ready to take up directing Space Ace on his own.

Space Ace is a goddamn holy grail for me. Not the cartoon itself, which is really just one of a number of stylish, weird, and cheaply-animated SF cartoons (see also: Prince Planet, Super Jetter, Space Boy Soran, Meteor Mask), but the dubbed version. I love hunting down old anime dubs, but Space Ace’s dub is one of a very few that seems to be completely unattainable, almost certainly lost. This is because it wasn't rerun for years in the US, like similar 60s anime favorites Astro Boy and Gigantor. Space Ace was aired on Melbourne, Australia's Channel 9 in 1968-- but this was before the age of the VCR, and the small pockets of older Aussie anime fans, like Glen Johnson (who has even more information about Space Ace on his site) haven't been able to turn up any of the film reels. The show's English version remains buried in time.

The thing is, the mere existence of a dub of Tatsunoko's very first TV cartoon is very telling. It's a demonstration that, from the beginning, Tatsunoko were absolutely hell-bent on getting their stuff onto the international market. Rival studio Mushi Production had lined their pockets with overseas money from hits like Kimba, and the Yoshidas wanted in on that action. While a mysterious dubbed version of the B&W Space Ace aired on TVs would air in Melbourne, Tatsunoko were also teaming up with an American TV producer-- one Fred Ladd, of Delphi Associates, who'd had success dubbing Astro Boy and Kimba for NBC and formed his own company to manage the popular Gigantor. Ladd knew that the sun was setting on black and white TV, and so was able to convince Tatsunoko to dig up the original pencil test animation of the first episode of Space Ace and re-animate it-- in color! The resulting pilot, which Ladd dubbed Ring-o (the title character flies around on a high-powered ring, see), drew some interest-- but no suitor wanted to foot the bill to redo the rest of the series in color. Ladd still owns a copy of that color pilot, and screens it from time to time.

Tatsunoko weren't able to spread Space Ace to every corner of the globe. But Tatsuo Yoshida, himself an accomplished cartoonist, had a great idea-- he'd combine the excitement of auto racing, and the stylishness and international backdrop of the popular James Bond movies. The resulting series, Mach Go! Go! Go!, would become Tatsunoko's first color cartoon, directed by Hitoshi Sasagawa. An American company called Trans-Lux snapped up the rights, hired an experienced actor and voiceover man named Peter Fernandez to dub it in English, retitled the affair Speed Racer, and the rest is history. There are two wrinkles to the early Speed Racer story that amuse me, though. The first one is that, during the show's production, Tatsunoko grew enough to start hiring more people. One of those people was a 16-year-old kid named Yoshitaka Amano. He was an excellent draftsman, an artist with a unique flair for stylish, easy-to-animate characters. Amano would go on to define the visuals for a huge part of Tatsunoko's productions, before splitting to become the character designer for a little video game franchise called Final Fantasy. The other funny thing is that, in spite of Speed Racer's broad marketability, Trans-Lux sold the series off in 1969 so they could go where the real money was: LED signboards! I guess that worked out OK for them, though, because they're still in business.

The studio would follow Speed Racer with a number of TV cartoons that went on to be huge hits around the world. Judo Boy, the Fugitive-esque tale of a young judo champ zooming across the countryside in pursuit of his father's killer, a man with one eye, somehow never made it stateside in spite of this incredibly fucking awesome opening. Seriously, look at this shit.

But Judo Boy, originally Kurenai Sanshiro, was a hit all across Europe. Hakushon Daimaoh, a much-loved TV comedy about a kid and his bumbling genie pal, also spread across the globe-- thought it wouldn't be until the late 1980s when the series, under the title Bob in the Bottle, made inroads in the English-speaking world. Cute-but-grim Honeybee Hutch would suffer a similar fate, enjoying success in Europe more than a decade before Saban scooped it out of the woodpile and dubbed it in English. Saban also snapped up a weird Pinocchio adaptation called Mokku of the Oak Tree-- under the title Adventures of Pinocchio, the show aired on HBO for a couple of years. Don't miss episode five, in which Pinocchio, in his quest to become a real boy, attempts to kidnap a child and remove its still-beating heart!

Despite a great track record of shows solidly marketed both at home and abroad, Tatsunoko's best days were still ahead of ‘em in the 1970s. Perhaps their biggest, most enduring hit ever would come in 1972, with Ippei Kuri's production of Science Ninja Team Gatchaman. The relentlessly action-packed, vivid, and weird adventures of five young men and women battling an intergalactic criminal conspiracy in colorful bird costumes captured the public's imagination; Kuri had swiped the dramatic stock “henshin” sequence from the previous year's Kamen Rider, and Kamen Rider creator Shotaro Ishinomori would respond in kind, grabbing Gatchaman's concept of five color-coded heroes for his super sentai project Goranger a few years later. The series ran for more than 200 episodes, including the sequels Gatchaman II and Gatchaman F. Closing theme “Gatchaman's Song” was such a broad hit that it was hurriedly shifted to the OP sequence midway through the series.

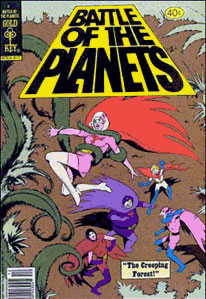

In the west, it'd take a few years for Gatchaman's star to rise, but rise it did-- and all thanks to B-movie and TV maven Sandy Frank. Frank was on the lookout for a foreign piece of science fiction that he could leverage to capitalize on the popularity of Star Wars, and in 1978 he used Gatchaman as that leverage. Redubbed Battle of the Planets, the adaptation is kind of busted in places-- wisecracking kid Jinpei is rendered inarticulate, and scenes of extreme violence are replaced with bad animation of 7-Zark-7, a charmingly terrible synthesis of R2D2 and C-3P0 that lectures the audience with the dulcet tones of Alan “Uncle Scrooge” Young. But despite that, Battle of the Planets is a fairly faithful adaptation, run through with TV stars like Casey Kasem and Keye Luke. The soundtrack, a melange of Bob Sakuma's original score and Hanna Barbera regular Hoyt Curtin's brassy craziness, is one of the best unplanned collaborations I've ever heard. You can still get it on CD! Battle of the Planets ran for years in syndication, and a wave of nostalgia for the title at the turn of the century led to DVD reissues, comic book tie-ins, new toys, and a lavish and irritatingly elusive set of DVD boxes from ADV Films. Thankfully, it looks like Sentai Filmworks is taking up the slack on home video.

That reach wasn't the extent of Gatchaman’s influence, though. The series had a direct impact on subsequent Tatsunoko shows, stoking the “henshin hero” boom that would give us colorfully costumed good guys like Robot Hunter Casshan and Hurricane Polymar. Polymar was one of the first major jobs for a mechanical designer named Kunio Okawara; because of the success of Polymar and other shows like it (he also worked on Gatchaman II), Okawara was able to more or less invent the title “mecha designer” for himself. A few years later, he'd design the original Gundam, the RX-78.

By this point, we're smack in the middle of the seventies and life is good for Tatsunoko. Well, maybe not that good-- Space Knight Tekkaman, an early foray into serious, high-stakes sci-fi, is quietly cancelled after only half of its original planned 52-episode run. Despite the setback, director Hiroshi Sasagawa is undaunted, and heads right into his next work, a family comedy series called Time Bokan. The concept is simple: two kids in silly costumes, plus their pet bird and talking robot pal, jump into a time machine after their mad scientist grandpa accidentally sends himself back in time. Opposing them are a trio of villains: a femme fatale, a skinny guy, and a squat guy with huge teeth. These folks.

Wait wait, I mean these folks.

These folks, I think?

Wrong again? Okay fine, it's these folks.

These folks, then? They seem like the right types…

ALRIGHT ALREADY.

Yeah, Time Bokan set the stage for a number of goofy formulas, and while the show was good fun, with time travel adventures that involved both historical and fantasy characters, it still ended after a year. Then, Tatsuo Yoshida died of cancer.

Man, cancer sucks. Dude was only 45! He was succeeded as president by his brother, Kenji. Tatsuo stuck around long enough to see his final creation, a Time Bokan spinoff called Yatterman, launch on New Year's Day-- but by the time the show's impact as a hit was really felt later in the year, he was in his sickbed. Yatterman turned the two-dumb-kids vs three-dumb-villains formula into a beloved institution, with crazily imaginative mecha, toilet humor, sight gags, and music that had families rushing to tune in every Saturday at 6pm. Rising tastemakers Yoshitaka Amano and Kunio Okawara drew the funny characters and fanciful mecha, and the faithful Sasagawa directed. More than anything else, Yatterman is the single closest analogue I've ever seen to Hanna Barbera's popular 60s and 70s fare like Scooby Doo and Yogi Bear. The animation is simple and the stories are pretty repetitive (there's a “gag of the week” involving a swarm of hilarious little mecha animals that makes me laugh like a goddamned simpleton every time), but there's a charm and inventiveness to the proceedings that make it persistently watchable and enjoyable, even thirty-five years later.

Not surprisingly, Tatsunoko would milk the Time Bokan cow until it keeled over, then set to work making hamburgers and wallets out of the carcass. Yatterman was followed by Zendaman, Otasukeman, Yattodetaman, and Ippatsuman, before the final installment, Itadakiman, was ignominiously cancelled in 1983. They'd occasionally go back to the Time Bokan well after that-- a peculiar OVA here, a forgettable 2000 sequel there-- but the franchise quieted down for the 80s and 90s. That's okay, because Tatsunoko, the little family animation studio that could, kept on doing stuff. Remember Superbook and The Flying House, the two separate shows that both featured nearly identical children and their robot pals using mysterious technology to travel back in time and live through the adventures of biblical heroes like Moses and Jesus? I'm pretty sure one or both of those shows still air on religious cable channels. Well, both of ‘em were brought to you by Tatsunoko! So was rollerskating henshin hero Muteking, kids’ funny animal romp Lil’ Bits, and a certain 1982 joint called Macross.

Alright, Tatsunoko didn't make Macross themselves. Studio Nue did the creative stuff, and the series was planned by Big West. But Tatsunoko did the heavy lifting, and importantly, they also handled business development for Macross overseas. When a company called Harmony Gold-- who'd already done plenty of business with Tatsunoko up to this point!-- came asking after Macross, Tatsunoko supplied the series, plus an incredibly poorly-worded contract that granted Harmony Gold rights to the Macross TV cartoon and trademarks outside of Japan more or less in perpetuity. When HG realized that they couldn't get a 36-episode series into daily syndication and had Carl Macek patch together Robotech, they went back to Tatsunoko and helped themselves to Southern Cross and Mospeada. (Fun fact: despite being chronologically earlier in Robotech, Southern Cross came out after Mospeada in Japan!) Decades later this agreement would more or less scupper the chances of seeing a legit release of newer Macross cartoons in the west-- but back then, it was good business for everyone.

Tatsunoko spent much of the 80s in an odd state of transition-- Kenji Yoshida stepped down and the reins were taken by Ippei Kuri. The studio dabbled in other ventures, like an animation training school, and did a lot of subcontracting work-- when they weren't kicking out Robotech II for Harmony Gold, they helped fund Megazone 23 and did some gruntwork on Akira, just like seemingly every other studio in Japan. They did close the decade with two sizable hits-- the laser tag cartoon commercial Zillion, and the archetypical Pretty Boys in Armor series Shurato.

Then, they made this thing! You can't really hang Samurai Pizza Cats on the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles-- TMNT is a little older, but it didn't make it to Japanese cable TV until 1991. Tatsunoko's Legendary Ninja Cats was a pretty typical kids show-- until it was seized by Saban for broadcast in the US. The show was adapted by a coterie of Los Angeles voice actors, many of whom (notably Robert Axelrod) have maintained that the scripts supplied to Saban were awful and/or nonexistent, so the team decided to rewrite the entire show. The resulting explosion of cultural references, bad puns, and outdated celebrity impressions (this show taught me who Charles Nelson-Reilly was!) has attracted a hell of a cult audience over the years. That cult is about to get their wish granted, because Discotek is releasing both versions of this show this summer, and... man. Anyone else just overwhelmed by the prospect of watching more than one episode of Samurai Pizza Cats? It's a fun little sign of the times, sure, but I can't help but view the idea of watching the entire series as something of an endurance test. Anyway! One final thing that cracks me up: the “we didn't have good scripts, so we made stuff up” story is also what drove Peter Fernandez and company to dub Speed Racer so freely. History repeats itself!

Aside from one of the best shows of the 90s (Irresponsible Captain Tylor, natch) Tatsunoko spent the 1990s mired in the Swamp of Remake. There was a Tekkaman remake (Tekkaman Blade, a stylish and dark take on the spacebound armored hero that easily eclipsed the original in popularity), a Casshan remake (nicely animated, not great), a Tekkaman Blade remake sequel (fanservice!), a Gatchaman OVA remake (really only notable for the Earth Wind & Fire tune in it), a Hurricane Polymar remake (about as good as the Casshan remake), and a Speed Racer remake.

No, it wasn't the bad American one. Ha! Man, that one was so awful. Like the above mentioned reduxes, Speed Racer X was dubbed an “anniversary project” by the studio, and even sported the aging Sasagawa returning to the director's chair. The series made some interesting changes to the formula, favoring long arcs over races that took place over one or two episodes, but it's fairly by-the-numbers. To me, the strangest thing about Speed Racer X is just how long it took to get localized-- I figured it for a shoo-in, but it didn't show up on Nickelodeon until 2002. Even more strangely, it's never been issued on DVD or rebroadcast in North America. We got that rubbish CG New Speed Racer cartoon instead. Ha ha! That was also terrible. Anyway, all that Speed Racer X really led to was a messy lawsuit, which might explain its curious absence.

Generator Gawl was dubbed a return to form by Tatsunoko, who tried to sell the series as a throwback to their henshin hero glory days. Unfortunately, it was pretty crappy. But you can't keep a good company down, and Tatsunoko rang the millennium in with The SoulTaker, which is absolutely the best example of their superhero shows since 1983's Urashiman. It was something of a breakout hit for director Akiyuki Shinbo-- the series had a tricky narrative structure, but Shinbo drew plaudits for its intense visual style. He'd spent the 90s directing middling OVA fare like… well, like that Polymar OVA, but Shinbo was able to parlay SoulTaker's artistic and commercial success into a string of better and better jobs. The SoulTaker isn't just about a hard-luck kid turning into a dark superhero-- it's the start of Akiyuki Shinbo's long transformation from the guy who directed Debutante Detective Corps into the guy who directed Madoka Magica.

Tatsunoko made an admirable attempt at raising the “dark hero” stakes with 2005's Karas. It has interesting cel-shaded CG effects, and the dubbed cast inexplicably sports B-movie stars like Matthew Lillard and Jay Hernandez. A bit sadly, 2005 also saw the company's reputation as a family-run animation studio come to an end, as the Yoshida family sold a controlling stake in the company to toymaker Takara. The company promptly hopped back on the remake n’ sequel gravy train, providing production assistance for Robotech: The Shadow Chronicles and turning out remakes of both Yatterman and Casshern. One big difference between these shows and the forgettable OVA remakes of the 90s? These ones are good, with real artistic verve. American anime fans already know and love Casshern Sins; hopefully Anime Sols will acquaint a few more of us with the zippy and fun Yatterman 2008.

It's hard to say where Tatsunoko will head next. The company's edged away from remakes in recent years-- the big-budget Speed Racer film might've netted them a huge windfall, if it hadn't flopped so badly, and the story repeated itself the following year with the Yatterman film. Plans for a second Yatterman film were quietly scrapped, and the studio could only watch from the sidelines as Imagi, who'd optioned Gatchaman for development as a big-budget CG movie, went out of business. Original fare, like C-Control and Muromi-san, have kept Tatsunoko relevant in fans’ minds. But as we near the apex of 2013, one truth prevails: it's time to take another crack at Gatchaman.

Fortunately, Tatsunoko are diversifying their approach. A “safe” live-action film from Nikkatsu is slated for August; time will tell if it hits the skids or actually succeeds. I think making a live-action Gatchaman is pretty risky business, so I'm glad that they're also working on Gatchaman Crowds, a summer animated project that looks completely different from any Gatcha-show before it. Casshern Sins was a surprisingly different take on the classic; I hope Gatchaman Crowds can follow in its footsteps.

As I sit here, waiting impatiently for the next Yatterman (every Thursday, gang!), I have to reflect on what a huge segment of Tatsunoko's catalog is comprised of mainstream hits, cult hits, or other trendsetters. It's easy to point at big studios like Toei and artistic maestros like Tezuka and Miyazaki as the standard-bearers of Japanese animation, but as far as I'm concerned, the Yoshida brothers might be the key figures, over the past five decades, in transforming anime from animation for Japan into animation that the entire world flocks to and enjoys. I hope the studio surprises the world again, and soon!

What's your favorite Tatsunoko show? And hey, what cons are everyone going to this summer? My profile next year will be low, since it'll be a World Cup year and Brazil will siphon away all my money. Last weekendI was talking at Anime Boston. Next week, I'm a guest no less at Anime NEXT. I'll be kicking around Anime Expo, and a featured speaker at Otakon. It's shaping up to be a good summer. How ‘bout you?

discuss this in the forum (40 posts) |