Brain Diving

The Youkai Show

by Brian Ruh,

All of a sudden this Halloween I got sick of your standard ghosts and ghouls, generic specters and werewolves, and especially overused zombies and vampires. I craved something different. Not necessarily something bloody and terrifying, just something kinda creepy and out of the ordinary. “Japanese monsters,” I thought. “That would do the trick.” Not big hulking gargantuans like Godzilla or Mothra, but the more intimate monsters of Japanese folklore known as youkai. My mind immediately went to the works of one man – Shigeru Mizuki.

There have been quite a few books written about Japanese monsters in the last few years, both academic – Civilization and Monsters: Spirits of Modernity in Meiji Japan (1999) by Gerald Figal and Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai (2008) by Michael Dylan Foster –and popular – Yokai Attack!: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide (2008) by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt and The Great Yokai Encyclopaedia (2010) by Richard Freeman, just to name a few. Plenty of youkai also appear throughout Japanese anime and manga, many of which can be traced to Mizuki's influence on manga's development from the 1960s onward. As just one example of this, while I was writing this article ANN reported that Mizuki was designated a “Person of Cultural Merit” by the Japanese government. But still, there's almost nothing by Shigeru Mizuki in English. I was curious, so I used WorldCat to look up how many titles by Shigeru Mizuki in English are held by libraries worldwide. The grand total was zero! This is completely unacceptable for an artist who has had such a large influence on postwar anime and manga.

Who was this Shigeru Mizuki guy? You might recognize him by his most famous creation – Gegege no Kitaro. It's about an undead kid named Kitaro and the adventures he has in the world of Japanese monsters. Before this hit, though, Mizuki created spooky stories for both the kamishibai (live storytelling) and kashihon (book rental) markets. In fact, the very first Kitaro stories were created as rental manga. Before this, Shigeru Mizuki had grown up listening to stories of youkai in rural Japan and later lost his left arm during World War II. (Mizuki was a southpaw, though, so even though he had been artistically inclined before the war, he had to train himself how to redraw everything using his non-dominant hand.) As manga began moving away from the rental market and more toward magazines, Mizuki's manga began running under the name Hakaba no Kitaro (or Graveyard Kitaro) in the avant-garde Garo magazine beginning in 1964. In 1967, Weekly Shounen Magazine picked up the manga and made it more child-friendly as Gegege no Kitaro. A black and white animated series of Kitaro began airing a year later, and so far not a decade has gone by that hasn't seen a new Kitaro animated series. In addition to the anime on television, there are also over ten Kitaro films, including a live action one from 2007.

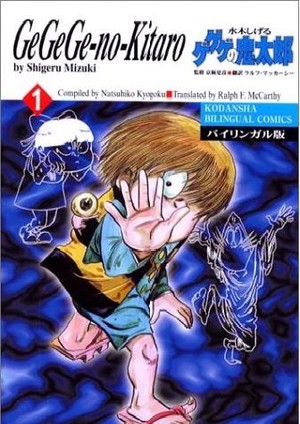

Although I said that no libraries seem to have any of Mizuki's work in English, in 2002 Kodansha did publish three volumes of Gegege no Kitaro in a bilingual edition. (It's just that no libraries anywhere seem to have them.) They seem to be fairly rare, though, so I haven't been able to get my hands on any copies. It would seem that the volumes are “best of” the Kitaro manga, since their covers say that they were compiled by Natsuhiko Kyogoku, another writer and expert on youkai. (Two of Kyogoku's books, Summer of the Ubume and Loups-Garous, have been published in English so far. Some of his novels have been turned into anime as well, including Loups-Garous, Mouryou no Hako, and Requiem from the Darkness.) Still, three difficult-to-obtain volumes are pale in comparison to Mizuki's mountain of manga and youkai catalogs in Japan, or even the respectable chunk that's been translated into French.

Although I said that no libraries seem to have any of Mizuki's work in English, in 2002 Kodansha did publish three volumes of Gegege no Kitaro in a bilingual edition. (It's just that no libraries anywhere seem to have them.) They seem to be fairly rare, though, so I haven't been able to get my hands on any copies. It would seem that the volumes are “best of” the Kitaro manga, since their covers say that they were compiled by Natsuhiko Kyogoku, another writer and expert on youkai. (Two of Kyogoku's books, Summer of the Ubume and Loups-Garous, have been published in English so far. Some of his novels have been turned into anime as well, including Loups-Garous, Mouryou no Hako, and Requiem from the Darkness.) Still, three difficult-to-obtain volumes are pale in comparison to Mizuki's mountain of manga and youkai catalogs in Japan, or even the respectable chunk that's been translated into French.

Knowing that finding any translated Shigeru Mizuki manga could take a while, I thought this would be a good time to check out the book Anime and its Roots in Early Japanese Monster Art by Zilia Papp. Like I've said in previous columns, I'm wary of the claims some make that anime has a direct lineage that can be traced back centuries to the earliest Japanese scrolls. Luckily this book isn't trying to make such an argument and it is actually a lot less general than it sounds. Rather than trying to say anime itself came from some quite old scrolls, Papp primarily writes about Shigeru Mizuki's manga and the relatively recent (eighteenth and nineteenth century) images of youkai that inspired them.

Before I get to Papp's book, though, I have two related articles for your Read This! pleasure this month. Both appear in the fourth issue of the journal Mechademia and are by scholars who have written about youkai. The first is by Zilia Papp herself, is called “Monsters at War: The Great Yōkai Wars, 1968–2005,” and is adapted from one of the later chapters in her book. (Publishing journal articles that later are incorporated as part of a book is pretty standard practice in academia.) In the article, Papp discusses the idea of the “youkai wars” that Mizuki first introduced in Gegege no Kitaro and is later adapted into the anime version as well as a live action feature film in 1968 and one by Takashi Miike in 2005. By making such comparisons, she traces how the images of the youkai have been used over time in postwar Japan. If you can't find a copy of Papp's book, or if you want to check out what she has to say before trying to track it down, this article is certainly recommended. While you're on the Project Muse page for Mechademia, you may want to read “Haunted Travelogue: Hometowns, Ghost Towns, and Memories of War” by Michael Dylan Foster. In it, Foster discusses Mizuki's hometown of Sakaiminato, which has become a shrine to Mizuki's youkai, which can be seen everywhere all over the town. Actually, the entire fourth issue of Mechademia is currently free to read at the Project MUSE website. If you're interested, I suggest checking it out – it's a scholarly journal that comes out on a yearly basis that focuses exclusively on anime, manga, and games. The fifth issue, which focuses on fans and fan studies, should be out later this month. (Disclaimer: I'm one of the journal's editors and I have an article coming out in the next issue. However, as with most things academic, I make absolutely no money no matter how many copies I manage to convince you to buy.)

Anime and its Roots in Early Japanese Monster Art by Zilia Papp

Anime and its Roots in Early Japanese Monster Art by Zilia Papp

Not only is this a very recent book, having just come out this year, but it's the first really “academic” book I've discussed so far in this column. Flipping through the book, you can tell that Papp isn't aiming for a popular audience. It's not that the language is terribly difficult or obtuse, but you'll certainly see references to other books and journal articles throughout. Another indicator that this is a strictly academic book is its price – it only comes in hardcover and its list price is $93. This is a surefire indication that this isn't a book you'll find at your local bookstore. When books are priced that way, you can be pretty sure that their main market is university libraries. If you don't have one near where you live, you local public library might be able to get you a copy through interlibrary loan.

Like I mentioned above, the title of Papp's book is a little misleading. She focuses mainly on the youkai scenes Mizuki Shigeru created in his manga, which were later animated forscreens both large and small. In doing so, she seeks to investigate how such imagery “has been influenced by youkai imagery created in the Edo to Meiji periods and demonstrate how the design of the characters of the contemporary animated series is an integral part of a process of visual evolution of the representation of monsters that began in the Muromachi period.” Papp spends a good part of her short introduction justifying, from an art history perspective, why comics like those of Mizuki are worthy of study. (Apparently there are still a number of people out there in the academic world, and in general for that matter, who still need to be convinced that it's possible to say scholarly, relevant, and interesting things about anime and manga.)

Papp's second chapter traces a short history of youkai from before recorded records up through the present day. She begins with the idea that youkai are beings that inhabit an in-between stage in the world. They are neither good nor evil. They are neither human beings nor gods. They are mysterious and changing. For these reasons, people feared youkai because they could not be concretely pinned down. However, youkai exist everywhere; Papp lists three main types of youkai – of the mountain, of the water, and of the village and home. Because of this, although youkai were written about in various stories, they did not appear in Japanese art until the Edo period (1603-1868). Papp goes into quite a bit of detail in this chapter, writing about specific artists and works of art. These details set the stage for her introduction of Shigeru Mizuki and Kitaro. For such a visually-oriented chapter, though, there are no pictures, which can be a hindrance if you're not well-versed in Japanese art.

In the third chapter, Papp begins by briefly giving a biography of Mizuki and how he came to create such an iconic manga like Gegege no Kitaro. She traces some of the characteristics of Kitaro (such as being born in a graveyard and only having one eye) to earlier Japanese and Buddhist texts. But it's the fourth chapter in which Papp draws most of the work in the book. (At nearly 75 pages, this chapter is over a third of the book by itself.) In this chapter, Papp tries to trace specific youkai that appear in Mizuki's manga and anime to historical precedents to see how they have changed over time and what this could possibly mean. Unlike the second chapter, there are plenty of illustrations throughout this chapter, often comparing the image of specific youkai from an old encyclopedic collection of Japanese monsters with those from Mizuki's manga and anime. The similarities are often quite striking, and it's often quite evident that Mizuki took the designs for some of his creatures straight from these eighteenth and nineteenth century collections. However, Papp notes that Mizuki was creative with his incorporation of youkai as well; some of his creations were not originally youkai but rather gods from Hindu, Buddhist, Shinto, and Taoist sources. Some of Mizuki's youkai designs came from masks that Mizuki collected from South Pacific islands like the one Mizuki had been forced to fight on during World War II. Still other youkai were Mizuki's original creations as well as historical figures. (Marilyn Monroe even makes an appearance as a youkai in one episode.) This chapter, which details the specific influences on specific youkai, is probably the most satisfying one of the book and makes for interesting reading by itself even if you skip the preceding chapters.

In the third chapter, Papp begins by briefly giving a biography of Mizuki and how he came to create such an iconic manga like Gegege no Kitaro. She traces some of the characteristics of Kitaro (such as being born in a graveyard and only having one eye) to earlier Japanese and Buddhist texts. But it's the fourth chapter in which Papp draws most of the work in the book. (At nearly 75 pages, this chapter is over a third of the book by itself.) In this chapter, Papp tries to trace specific youkai that appear in Mizuki's manga and anime to historical precedents to see how they have changed over time and what this could possibly mean. Unlike the second chapter, there are plenty of illustrations throughout this chapter, often comparing the image of specific youkai from an old encyclopedic collection of Japanese monsters with those from Mizuki's manga and anime. The similarities are often quite striking, and it's often quite evident that Mizuki took the designs for some of his creatures straight from these eighteenth and nineteenth century collections. However, Papp notes that Mizuki was creative with his incorporation of youkai as well; some of his creations were not originally youkai but rather gods from Hindu, Buddhist, Shinto, and Taoist sources. Some of Mizuki's youkai designs came from masks that Mizuki collected from South Pacific islands like the one Mizuki had been forced to fight on during World War II. Still other youkai were Mizuki's original creations as well as historical figures. (Marilyn Monroe even makes an appearance as a youkai in one episode.) This chapter, which details the specific influences on specific youkai, is probably the most satisfying one of the book and makes for interesting reading by itself even if you skip the preceding chapters.

The last chapter before the conclusion presents a short history of youkai in Japanese film from the late 1960s through 2008. This is the chapter that much of the Mechademia article reworks. Papp spends a few pages discussing the character designs in Takashi Miike's Great Yokai War, which she knew about firsthand since she played a youkai extra in the film. She also briefly mentions the manga and adaptations of Tezuka's Dororo and Kazuo Umezu's Cat Eyed Boy. This is probably the least satisfying chapter, if only because Papp sets her sights too high. A single chapter can't provide an in-depth look at youkai in Japanese film – it would probably take an entirely separate book in order to do that well.

It's to Papp's credit that she manages to make her subject matter interesting even though we don't have ready access to officially translated versions the Mizuki manga or anime. Like I said, this is an academic book, so it's not necessarily going to jump off the page with its prose stylings. It's more important to effectively communicate the information to the reader, and Papp does a good job of this. Since there are so many anime and manga out there that refer to youkai, you might want to take a look at this book if you're interested in increasing your knowledge of Japanese pop culture.

It's a bit of a consolation that in July Drawn & Quarterly announced the license of two titles by Shigeru Mizuki – Toward Our Noble Deaths and Nonnonba. The first is a semi-autobiographical tale of Mizuki's time fighting in the Pacific theater during World War II. Although the second is also semi-autobiographical, it is more closely related to the ghost stories like Kitaro that Mizuki in known for. Nonnonba is about a young boy who listens to the supernatural tales of an old woman in his village and draws artistic inspiration from them. I'm excited to finally be seeing at least some of Mizuki's work in English. However, it's no Kitaro. Hopefully, if these two manga do well for D&Q, we'll be able to see some Gegege no Kitaro on our shores in the near future.

Brian Ruh is the author of Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. You can find him on Twitter at @animeresearch.

discuss this in the forum (14 posts) |