Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girls index

**** I'm not long back from viewing this in 3D at Hoyts Imax in Highpoint West (a suburb of Melbourne). Ghost in the Shell (live action)

Reason for watching: I wouldn't have missed this for quids, though I must admit to approaching it with both anticipation and trepidation: anticipation of the benefits that a Hollywood (even though it was mostly shot in New Zealand) budget would bring to an anime franchise; and trepidation that an insensitive interpretation of the underlying themes might traduce something with a honourable and long-standing tradition. Crucial to how both these factors might play out would be how well Scarlett Johansson carried off the role of the Major. Given that I've only just seen the movie, this post is more a record of my impressions than a review. The images are from the trailer on the Hoyts website. Technical Issues: Hoyts/Imax fluffed it. The film began without sound right through the Major's construction sequence, the opening credits, the Major's awakening and conversation with Dr Ouelet, and the early parts of the geisha hacking sequence. At this point the film (or should I say file) was stopped and restarted, with some improvement but still quite unsatisfactory. This time the sound didn't kick in until the Major awakened. Hoyts didn't bother trying a third time. It was a crap effort from Hoyts, Imax and the film's distributors, especially at the premium Imax price we all paid. Synopsis: The Major is an agent with the Public Security Section 9, whose task is to combat hacking and other cyber crimes in a world where people readily enhance their bodies and consciousness with cybernetic implants. She is the first and, so far, only successful instance of a human brain implanted into an otherwise fully cybernetic body, although she can remember virtually nothing prior to the procedure. When scientists and other officials from the Hanka Corporation - the very organisation that rebuilt the Major - are murdered after having their minds hacked, the Major must not only hunt down the perpetrator, but she must also uncover the truth of her own past.

Comments: Let's get the most important thing out of the way. Scarlett Johansson succeeds as the Major with some applomb. She mightn't give a blistering acting performance that'll earn her award nominations, but the essential persona she portrays - serious, somewhat aloof, intelligent and capable - is in keeping with her anime predecessors. Most importantly, Scarlett Johansson has a commanding presence, so essential for the character. Nevertheless, her forefronted doubts and fears mark her as different from earlier versions. Where those Majors were magnificent cyborg shells with a bemused human ghost, Johansson's is an agitated ghost finding itself in, yes, a magnificent yet alarming shell. It makes her the most human version so far. An emotional reunion late in the film is unlike anything in the franchise so far. It also works. Perhaps it helps that the Major has a human face on screen for the first time. Mind you, human face or no, she looks convincingly like the Majors I've come to know and appreciate. It must also be said that all previous animated Majors have taken liberties with the original manga and differed from each other in designs, personalities and back stories. Speaking of back stories, this is yet another origin story. Unlike the Mamoru Oshii film, which examines what the Major is and what she will become, or the Kenji Kamayama Stand Alone Complex series, which explore the implications of ghost hacking and cybernetics within the structure of police procedurals, Rupert Sanders's film looks firmly backwards into her past. It is all about revealing to us who she really is. The implication is that more is to come. That's OK with me. The rest of the Section 9 crew dutifully play their roles, though they are more multicultural than formerly. Of them, only Batou and Arimaki get significant screen time. Pilou Asbæk's Batou is more cuddly polar bear than the trigger-happy killer found in the various anime. I like him better for it. Takeshi Kitano's subtitled Japanese speaking Aramaki is bizarre. If the script writers are giving the finger to naysayers then I applaud it, if it's appeasement then I'm bemused. Either way it's an unnecessary annoyance. Funny that I don't mind subtitles in the various anime. Kitano isn't convincing in the role, having the startled look of someone who has had too many facelifts, rather than the simian wisdom seen previously.

Even more successful than Scarlett Johansson are the wondrous city scapes. With the deep-field 3D visuals and the skyscraper sized holographic advertisements, this is Ridley Scott's Blade Runner taken to the nth degree. Rupert Sanders takes those notions and similarly expands the grimy Hong Kong world of Oshii's original film to give us a vision that may not be altogether original, but is nonetheless glorious in its beauty and its ugliness. Look closely and you will find constant nods to the backgrounds of the two Oshii films. If only it would dwell on those visuals in the same way that Oshii did. I miss those ruminative moments. The film is let down from time to time with cheesy 3D gimmicks. Objects or people that come out of the screen may startle, but the effect eventually irritates. Also less than convincing are some of the interior settings that seem cheap and lacking in creativity. Even more disappointing is the prosaic, by the numbers soundtrack. The electronic drones and sequenced rhythms may be intended to suggest the artificialty of the Ghost in the Shell world, but they fail to go that extra, inspired step. They lack either Kenji Kawai's unearthly vocal harmonies so memorable in Mamoru Oshii's films, or Yoko Kanno's techno soundtrack that added such urgency to Kenji Kamiyama's TV series. The live action film likes to tease - constantly playing the cymbals that introduce kawai's justly admired Ghost City. We finally get relief as the end credits roll.

On a cerebral and, dare I say it, ruminative level, the film plays out the cyborg/human dilemma reasonably successfully thanks to Johansson's portrayal of the Major. What disturbs is the way the conflict with the ulitmate, underlying villain is played out. Where the Oshii film is about possibilities and where the Kamiyama series are about justice, the live-action film falls back on retribution and revenge. THAT is a step backwards. Rating: the low end of very good, though I may modify that as I become more familiar with it. On the positive side Scarlett Johansson gives a new, more intimate version of the Major while preserving her commanding presence in a flim that is consistently a visual treat while paying homage to the original Mamoru Oshii films. On the down side the soundtrack is forgettable, Aramaki hard to take seriously and the final resolution lets the film down. Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Apr 28, 2018 11:46 am; edited 2 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Touma

Posts: 2651 Location: Colorado, USA |

|

||

|

I really want this movie to be one that I will enjoy.

After reading the many comments about how terrible it will be, from people who have not seen it, it is reassuring to read a positive review from somebody who has seen it. Thank you. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

You're most welcome. I hope you enjoy it when you get the chance to see it.

|

|||

|

|||

|

Night fox

Posts: 561 Location: Sweden |

|

||

|

I'm relieved to hear that Scarlett got a thumbs up from you. How the main character is portrayed is so important for the overall impression of a movie, after all. Since I live fairly close to an IMAX-theater myself, I'll probably see the 3D-version too. The downside seems to be the plot's vengeance-theme (which has been done enough in countless other hollywood productions), I'd been hoping for a more philosophical approach. Which brings me to:

So, they're planning a sequel then (Where they explore the meaning of life, the universe and everything)? |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

I think the vengeance resolution is symptomatic of the issue that other reviewers have been mentioning - the indifferent screenplay. There are, to my mind, two reasons behind that. 1. The shortcomings of the original Mamoru Oshii film. There isn't a lot of substance to the original film. It's strengths are its original concept, the visuals in many of scenes, and Kenji Kawai's musical composition. The story isn't complicated, nor is the philosophy explored in any depth. Of course, we've lost Kenji Kawai until the end credits. 2. The narrative of the live action film is about the Major. In the original she was the dominant character, but the narrative was about the villain and her ultimate relationship with the villain. Shifting the narrative to her makes the film more emotional - to the moderate extant that is - and therefore less cerebral. To those of us who like the franchise for its cerebral games the new film, while visually outstanding and while Scarlett Johansson is quite good, there is a sense of a lack of substance. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Three commercially released flims in three weeks. The Project is being delayed again and again.

A Silent Voice Reason for watching: The premise of someone trying to atone for their behaviour resonates with me. I've done plenty of things in my time that I wish I could undo. Also, anime seems to be becoming generally accepted as cinema entertainment in Australia, with this being yet another example of a widespread release. Another sign of anime's growing popularity is that all the best seats for the first two nights at Hoyts Melbourne Central had been booked by the time I got online. The session times at their suburban complexes were awkward to manage after work and, in any case, after screwing up the sound for Ghost in the Shell I wasn't inclined to give Hoyts more of my money, so I headed off to the more intimate theatres of the Nova in Carlton. The images are from the Madman trailer.

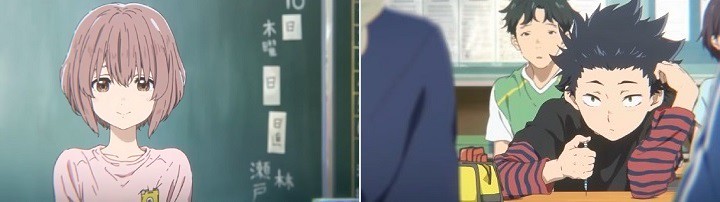

Shoya is intrigued by the arrival of the mysterious transfer student. Warning: a tad spoilerific. Synopsis: When a new girl, the severely deaf Shoko Nishimiya, starts at Shoya Ishida's elementary school, he leads a cabal of students in bullying her. Eventually the school and parents intervene. Shoko is transferred yet again, while Shoya's former confederates abandon him, leaving him to bear alone the odium of their behaviour. By the time he's a high school student he is ostracised and bullied in much the same way Shoko had been. Now more aware of how she had suffered and remorseful for his former behaviour, he seeks out Shoko to both help her overcome her difficulities in connecting with other people, but also to get his own life back on track. Comments: For the most part anime evolves steadily, if slowly. It's easy to criticise anime studios such as Kyoto Animation - the makers of A Silent Voice - for their seemingly conservative approach to their productions. It's as if they know their market and happily pander to it year in, year out. But then, when I compare this new film with, say, 2007's Clannad, I quickly realise how far the company has come in that time. Kyoto Animation has always preferred character based plots (even if the characters were frequently moe archetypes) to thematic based plots, but where this movie shines is in its intimate character study of Shoya and, to a lesser extent, Shoko. Despite their two dimensional appearance and conservative character designs, Sho1 and Sho2 (

Image exposure creates an intentional emotional distancing from Shoko. I'll start with Shoko because, while she isn't the protagonist, she is the catalyst for the story. One of the most impressive things about the film is how, while she clearly good-natured, there is something slightly repellant about her: a combination of obtuseness, diffidence, stubborness and an inability to communicate her feelings. This last is more than just a case of her deafness and incoherent vocalisations, but is also aggravated by her tormentors' refusal to listen, through spite and impatience - they won't learn sign language or indulge her handwritten messages. Looking back at the victims of bullying I witnessed in my school days and later, that combination of seeming dumbness (though, in hindsight, they weren't unintelligent - it was probably fear that made them appear that way) and unpleasantness (again no doubt accentuated by their fear) were common features. Part of Shoko's stubborness is that she is actually sweet on Shoya, causing her to endure more than she might otherwise. The presence of the admirer who won't go away, whether true or imagined, is its own source of aggravation for someone as emotionally insecure as Shoya. Her development isn't as closely argued as his, so seems a little less convincing. Indeed, her role recedes somewhat toward the end, though she is pivotal to the film's dramatic climax. In a realistic portrayal of high school romance, the two never manage to express their attraction for each other. You might say the affair is left dangling. One unsuccessful attempt by Shoko to tell Shoya her feelings is a highlight of the film. Shoya's development is a step-by-step process. He begins as insider and bully, in an instant becomes outsider and bullied in a sequence that doesn't quite convince, then sets out to make amends for the damage he has done - for both self-centred and altruistic reasons. He will come to understand his own motivations and how his behaviour affects others. He will also begin to see things from other people's perspectives, which will reconnect him with them. An interesting aspect of the film is that his redemption won't come from an act of forgiveness from Shoko; instead it begins with self-awareness and is completed when he is readmitted into the community. That is to say, accepted as a friend by his peers. The notion of belonging to a larger whole is a very Japanese one. It's also, to my culturally determined eyes, conservative and alarmingly conformist. You can find a similar argument in ERASED where the protagonist repeatedly fails when acting alone, before succeeding when part of a supportive team. Why Shoya bullies Shoko is never made explicit. Whether that's a weakness or subtlety of the scipt I'm not sure. After all, he is otherwise a good hearted kid. It might be surmised that his bullying compensates for his unsettled family life and a lack of any close friends. Perhaps pushing away the girl he likes and pities, and who might just like him, might assuage the alarm his emotions create.

Shoya's perpetual startled expression unintentionally impedes appreciation of his emotional progress. The support characters also have their complications and development journeys. There's a blunt girl, Naoka Ueno, who can't abide Shoko, so becomes Shoya's most enthusiastic ally in the bullying. Her path to self-awareness will entail learning how to separate emotions and behaviours. Another girl, Miki Kawai, whose hypocrisies always managed to draw the strongest responses from the audience, must learn that she isn't the centre of the universe. Miyoko Sahara will acknowledge that being a bystander to bullying also makes her culpable. The stumpy Tomohiro Nagatsuka - with a character design that doesn't fit the film's aesthetic vision - has no conception what friendship entails, but that makes him endearing in his own peculiar way. Best of all the support characters is Shoko's younger sibling. I won't say anything about the character, not even mention their gender, to avoid spoiling the suprises and the entertainment they provide. An instant classic character. There's a teacher who lets things slide until the principal intervenes, only then acting decisively (and in a way that makes the aftermath more difficult for Shoya than it needed to be) and a wise and foolish mother who is unable to give the emotional support Shoya needs, but then marvellously steers him away from some seriously self-destructive behaviour. A strength of the film is how it manages to integrate all the character journeys mostly seemlessly into the narrative. There are issues nonetheless. There are plot turns that are portrayed figuratively that I didn't fully comprehend. I never know whether that's my fault or the film's. I'm sure while watching it at home in the future I'll better understand what's going on. That's anime, I guess. There's also the problem of how a deaf person can glean anything useful in a classroom setting without professional assistance. I suppose that's a real life dilemma: such children are arguably best off in a normal classroom setting but how on earth can they make sense of what the teacher is saying. I've aleady mentioned that Shoya's motivation for his bullying is left to speculation. The depiction of his descent into being bullied is trite, as is a moment late in the film where his friends (see image below) suddenly desert him. The moment they all return is just as bad, despite the attempt to pass it off humorously. The film progresses its story methodically, but it could have economised more.

An older Shoya and his friends. L-R: Miyoka Sahara, Shoko Nishimiya, Shoko's younger sibling, Tomohiro Nagatsuka, Shoya, Naoka Ueno, Miki Kawai and Satoshi Mashiba. The blue cross is a visual cue telling us the characters estranged from Shoya. My surprise at this film getting a multi-cinema release was allayed when, researching this review, I learned that it was directed by Naoko Yamada, who also brought us K-ON! (at the age of 25!), Tamako Market and Tamako Love Story, as well as the first season of Sound! Euphonium. Clearly she's an up and coming directorial star. Previously I've never got past the first episodes of either K-ON or Tamako Market. Given my negative reactions to them, A Silent Voice is something of a surprise. Visually, it's KyoAni attractive, without breaking any new ground. The character designs are the weakest element, being rather more generic than the complex characters they harbour and in two instances - the perpetually startled Shoya and the creepily cartoonish head on Tomohiro - spoil the visual pleasure of the film. The film plays around with light exposure levels, not always to good effect. To give two examples the second image above works reasonably well, but in the one immediately above the characters are too evenly lit for the setting they're in. The music, when applied, sensitively embellishes the film. There's a chime sequence that caught my attention that is both urgent and emotional. Loved the OP song. Now, where has an old fart like me heard that before? Rating: The problem I have when rating an anime like this is that I'm not its intended audience. By way of contrast, consider Ghost in the Shell above. I am fair, square part of that film's demographic: an Anglophone long-time fan of the franchise with a preference for strong female lead characters and for plots driven by philosophical concepts rather than adolescent rites of passage. I enjoyed it thoroughly, in spite of its, by now, well publicised shortcomings in the screenplay. When I got home from watching A Silent Voice two days ago I rated it as good. Thinking it about it since, I've concluded that, for its likely audience and for its genre, it's better than that, so very good, with reservations.

Shoko gets a soaking. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

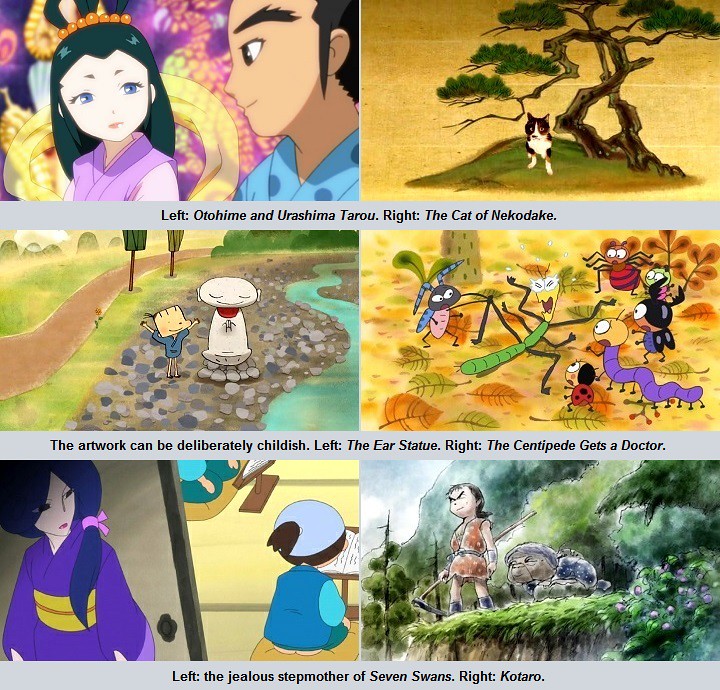

Folktales from Japan or, to give it its full title, Hometown Rebuilding: Folktales from Japan.

Reason for watching: The series started so long ago I can only suppose that I was interested in learning about the Japanese myths behind many anime stories. Background: The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, along with the ensuing tsunami and the nuclear meltdowns at the Fukushima powerplant, was the greatest disaster to strike Japan since World War 2. The Japanese National Police Agency put the toll at 15,894 deaths, 6,152 injured and 2,562 missing. It is thought to be the costliest natural disaster in history at over US$235 billion. In its wake there were fears that the anime industry would be severely affected. Remember, this was coming on top of the Great Recession following the Global Financial Crisis. That crisis, for its part, led to the bursting of the anime bubble in the US. I recall reports at the time of production difficulties leading to some episodes failing to meet deadlines and some studios relocating. In hindsight the industry took the setback in its stride, although there was a period where shortcuts were apparent. The production shortcomings of something like Kill Me Baby were a sign of the times. Yet Japan did what Japan has traditionally done: put its head down and strove to overcome the problems through hard work and perseverance. Hometown Rebuilding: Folktales from Japan reflects the times. It was not only billed as giving animators a fillip, it also promoted the values favoured in difficult times: hard work, thrift, honesty, decency, generosity, and respect for authority and tradition. Comments: The format of each episode was simple: three independent segments, telling a tradtional Japanese story. The only things shared by the segments were a) the two seiyuu - Yoneko Matsukene and Akira Emoto who, between them, voiced every single part over the 258 episode run; b) the keyboard music, which, though rarely repeated, was clearly improvised by the same team - ANN simply lists Kazuko and Keiichi Goto as the musical directors; and c) in most episodes, the opening words "Mukashi Banashi", which would be the Japanese equivalent of "once upon a time". For a time each episode contained one repeated segment. Further, some stories were told multiple times in different styles, while some basic tropes appeared in many variations - frugal old couples whose humble behaviour has them richly rewarded; young men whose kindness to animals earns them transformed animal wives with strings attached; the endless shenanigans of foxes and tanuka; or the travails of monks and their novices, to name just four. The segments, particularly early on, either told famous stories, such as the exploits of Momotaro the Peach Boy or the (literally) star-crossed lovers of Tanabata, or simple tales with a moral. Typical of the latter would be the old wood cutter who finds himself lost in a forest, encounters magical creatures, treats them well and is rewarded with treasure. When his lazy, avaricious neighbours find out, they bully the magical creatures and are suitably punished for their efforts. Later the series would become more adventurous. Segments built around a gag were common from the start, but tragedies and horror stories became more frequent later in the run. Some tales even explored marital infidelity. That the series won a "Children's Cultural Welfare Prize" from the Japanese Government suggests that the Japanese can be as relaxed as anybody else when it comes to the material presented to children.

What stands out when watching this series at any stage during the run are the basic production values. There is next to no animation, the artwork is simplistic, as already mentioned there are only two voice actors, and the musical orchestration is minimal. I wouldn't be the least surprised if, following the examples of the voice actors, the two musical directors improvised the music and played all the instruments. That said, and storytelling qualities aside, there are two areas where the series is outstanding. Visually, the series is more adventurous than most mainstream anime series, with a variety of styles not often seen elsewhere, be they impressionistic, expressionistic, naive, or sometimes downright bizarre or even ugly. The images I've chosen for this review should give some idea of the extraordinary range. I imagine the producers gave the segment directors considerable lattitude in how they presented their tales. Equally impressive are the voice actors, particularly Yoneko Matsukane whose characters covered either gender at any age. I especially liked her simpleton adult male characters, her old women and her children. Not so good were her young women, who always seemed too yamato nadeshiko for my tastes. That may have been deliberate, but they lacked the comic nuances that made her other characters as amusing as they are. Akira Emoto's (how's that for an anime surname!) only shortcoming was that he sometimes sounded too old for the characters he was voicing. I also can't recall that he ever voiced young women characters. Those points aside, his comic enunciation was as much a pleasure as his partner's. The two could handle ensemble dialogue with aplomb - there could be a six-way conversation that sounded as if six different people were voicing the characters. The longer the series went, the more I appreciated their efforts.

Rating: So-so. If this were a 26 episode series containing the 78 best segments from the five year run, it would be outstanding. As it is, there's way too much dross and repetition. For every one memorable segment there were five utterly forgettable. As it was, after two years, let alone five, I was beginning to wonder if I would ever finish the series. Watching one episode a week wasn't a chore but I have no intention of watching its sequel series, Hometown Visiting: Folktales from Japan. It seems the time for reinforcing traditional work efforts in the wake of disaster is past; the new title suggests a more nostalgic homage to traditional values. **** My next review, unless something unexpected happens, will steer me back towards the path of The Great Project. |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

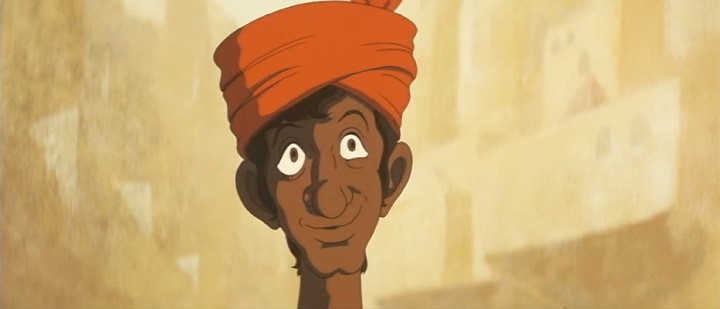

Senya Ichiya Monogatari (ie, Tales of a Thousand and One Nights)

Diverse characters from the film (clockwise from top left): The police chief's prediliction for mood altering substances ensures he relies heavily on his assistant, the aptly name Badli; Badli with adopted daughter, Jalis (who is actually the daughter of Aladdin and Miriam); Havahslakum, the police chief's pampered son - note the long hair and beads befitting a hippie; Feisty Mahdya, the bandit leader's daughter who gets a raw deal from everyone, including Aladdin; Aladdin in prosperous Sinbad guise; and The King of Baghdad is startled by the fruits of Sinbad's wealth. Reason for watching: As part of the Grand Project I'll be covering Cleopatra and Belladonna of Sadness. Senya Ichiya Monogatari is often included with those films in a sort of hindsight designated trilogy. For sure all three came from Mushi Pro, were directed by Eiichi Yamamoto and willingly foreground their sexual elements, but, as far as I can tell, there was never any stated intent from Mushi, Osamu Tezuka or Yamamoto to make a trilogy. In his Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements says that Tezuka had simply concluded that the adult cinema would be more lucrative than children's animation was proving to be. By the time the third film was being made - Belladonna of Sadness - Tezuka was no longer president of the company. Tonally, that film has little in common with the two made under his aegis. That all said, it would remiss of me to not to review all three movies. Synopsis: Coming to Baghdad the impoverished water seller Aldin (Aladdin) is enchanted by Miriam, a slave girl being sold at auction. He steals her, setting off a loosely connected sequence of episodes that include a den of thieves (Open Sesame!) who indulge in psychedelic freak-outs; a drug-addled police chief whose wife frequents said freak-outs, whose pampered, idiotic son purchased Miriam, and whose off-sider manipulates all and sundry to his own advantage. There's an island of nymphomaniac lamia who are happy to indulge any male who strays their way so long as their true nature isn't revealed. There's another island with triple-eyed giants who do battle against rocs. You can throw in a magical talking ship that can grant any wish, a bickering, shape-changing djinn couple, and a stupendous competition between the king of Baghdad and Sinbad - formerly Aldin but now swimming in wealth, thanks to the aforementioned ship - to determine who has the most mind-bogglingly amazing collection of treasures.Things culminate with Aldin/Sinbad crowned as the king of Baghdad and building a tower to reach the sun that, of course, collapses. Aldin leaves Baghdad the way he arrived - as a penniless water seller.

Miriam at auction. Provocative in so many ways. Comments: Senya Ichiya Monogatari is like no anime today. Very loosely Inspired by the tales of Aladdin, Ali Baba and Sinbad (none of which, incidentally, were part of the original collection of tales - they were added by European translators), the film adds a late sixties sensibility (it premiered in 1969) that makes it both distinctive and locks it firmly into the era. The tone is set from the very first beats as Aladdin, bearing a goofy grin of expectation, strides towards Baghdad to a psychedelic blues tune built around two distorted guitars and a base brought forward in the mix. He might just as well be walking to San Francisco. The hippie feel continues with a more wanton psychedelia as the forty thieves cavort in their cave with an unfortunate woman. Those darker rhythms also accompany a violent home invasion of the voyeur Suleiman and bloody sword fight between the thieves and the forces of the treacherous assistant to the police chief. Aladdin strides through it all, doing as he pleases, loyal to no-one, disrespectful of all, always on the fringes except for a brief period as King of Baghdad. Aladdin may be the hippie outsider but the structure of the film also fits another longstanding story telling tradition. He is the picaro in a picaresque tale. It is his story and nobody else's - all other characters come and go - they are disposable in a story telling sense. He is an outsider of low social status who gets by on his wits. What there is of a plot is a sequence of losely connected episodes - there are sudden changes of focus or direction and fantastical creatures or things intervene unexpectedly. While not precisely satirical all the characters are ridiculous, even the hero, who is a rogue who operates on the edge of the law. Yet he is likeable, thanks partly to his foolish grin and his unquenchable optimism, but mostly because he makes fools of the pompous, idiotic and villainous characters he meets. Once the viewer latches on to that last quality, watching him becomes more rewarding.

In the lair of the forty thieves. Rape as a sequence of gag images wouldn't go down well these days. In the tradition of the picaresque novel and representative of the "free love" of the sixties, the film happily indulges it penchant for sex, three years before Ralph Bakshi's Fritz the Cat made a fortune using a similar formula of sex and satire. Yes, the film contrasts the joyful unions between Aladdin and Miriam and between Jalis and Aslan with the thieve's rape of the unnamed woman in the lair, Badli's rape of Mahdya, Suleiman's voyeurism, Havahslakum juvenile simpering after Miriam and the djinns' jealous bickering, but I can't help but feel that the film is, as a product of its time, mysoginistic. Sometimes "free love" could be spin for easy sex for men. As in the earlier Mushi Pro films I've considered recently, while Tezuka and Yamamoto are usually, though not always, sympathetic towards their female characters, their presentation can be male-centric. Take the image above, taken from a scene in the bandits' lair. The rapists are depersonalised thanks to their uniform grinning and distorted representation. They are clearly unsavoury in their intent and their actions. The woman elicits sympathy due to her somewhat more realistic depiction and the shock in her eyes. But.. but.. it's meant to be funny. It may be creatively animated, but it's disturbing nonetheless. She doesn't appear before or after the scene. She remains unnamed. Her role is to provide a few seconds of entertainment for the viewer. Mahdya, the wilful daughter of Kamhakim the bandit chief, remains victim throughout despite her nature. Her only recourse is revenge. Miriam and Jalis have no role beyond being objects of desire. Emblematic of the issue are the lamia who present themselves as voluptuous women to the lucky/unlucky men who wash up on their island (Greek mythology intrudes into the film from time to time), but in their secret lairs revert back to their snake form. They are male longing and fear given visual form. Given the film's overall mildly satirical slant one might argue that the film is having a dig at male self-importance, but I'll leave that to the viewer.

Be careful what you wish for. Where there is choice there is misery.* Thing is, both the comic tone and design of the females, with some exceptions, are presented for the pleasure of the viewer. The stronger female characters - Mahdya, the police chief's wife, the Lamia queen - have the least appealing designs. Apart from the reservations I've already voiced there are other moments that elicit different responses. The climax of the tryst between Miriam and Aladdin is depicted figuratively by a "camera" zooming into a flower, past the petals, the stigmas and stamens and deep into the stem. The metaphor doesn't quite match real human anatomy but it's so corny, so kitsch, that it's funny. Perhaps it's intentionally funny - the film is a comedy after all. People's humour can be hard to fathom at times. More inventive and arresting is a sequence from Aladdin's night on the island of the Lamia. Using pencil shadings against an entirely, and perhaps too obvious, lurid pink background, it is a writhing tangle of limbs, fingers and other body parts that continually transform to suggest intimate, erotic exploration. Ignoring these concerns and stepping away from the current anime aesthetic we are all accustomed to, the film is a visual treat, infused with the wit and invention I have come to expect from Mushi productions. Somewhat like Masaaki Yuasa's Mind Game, though without the manic variation or frequency, the film uses different art and animation styles to suit the tone of a scene. As always with Mushi, there is a constant sense of activity, even when there isn't much animation. Despite Mushi's reputed financial difficulties at the time, there are scenes with complex animation. Awkward moments do intrude from time to time. In the opening scene of Aladdin tramping across the desert, the dunes aren't receding beneath his feet, which suggests shortcutting, but may have been a deliberate effect. If the latter, it doesn't convince. Some of the live images - used as backgrounds or as framing shots - mesh awkwardly with the rest of the film. I'm thinking of the model used to depict Baghdad, an aerial scene using a model of an oasis in the desert, and the magical ship sailing on live-action film of the sea. Because of the use of different visual styles throughout, the film just manages to get away with these intrusive efforts.

Night on Lamia Island. The music from Isao Tomita is a highlight, from the bluesy opener I mentioned earlier to the more freaky music that gives the film a desperate, edgy feel. The pink sequence uses more abstract sound effects, while there's a brassy, breezy, percussive variation on the opening tune for more upbeat parts of the film such as the first scene on the flying wooden horse. My grasp of musical theory is scant but my ear tells me that, probably, all the tunes are variations on a theme. Given that the romantic scenes use "The Young Prince and Princess" from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade (named for the character who narrates the stories in the original One Thousand and One Nights) then I suspect the theme is derived from there. Music is very elastic. Rating: good. Despite the sometimes dubious treatment of its female characters and an aesthetic that may not appeal to present day anime viewers, Senya Ichiya Monogatari is a fun, picaresque film that goes in a direction not seen before in animation. Unlike earlier Mushi Pro TV series such as Astro Boy or Princess Knight that spawned whole genres of anime, this is the first of three films that led into a creative and financial dead end for the company. Apparently it did well in Japan but its budget relied upon overseas success that wasn't forthcoming. It deserved a better fate.

Aldin/Aladdin. According to Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy he was modelled on the French actor, Jean-Paul Belmondo.** * Just keeping with the late 60s hippie vibe. ** And Badli had sex with a crocodile? Really? |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

The upheavals happening within the torrenting community will have some impact on this project. It could have been worse. In Australia content providers not long ago acquired the right to force ISPs to block access to torrent hosting sites. I expected the big name sites to get the chop quickly (which happened), whereas I thought the smaller anime specialist sites would remain around a little longer. Newer titles are, for the most part, available on DVD or streamed on licenced sites. It's the older, otherwise unobtainable titles that are of concern to me. Seeing the writing on the wall some time ago, I've been downloading older series as quickly as Australia's archaic internet speeds and limited bandwidth have allowed. My suburb is particularly bad - wireless internet is the best of a set of bad options. The following anime are at risk of not being reviewed:

Heidi, Girl of the Alps: almost complete - I'm hopeful of getting all 52 episodes, but at 1GB per episode for the second half of the series it's straining my internet resources Majokko Megu-chan: I only recently discovered this oddity of a magical girl show Hana no Ko Lunlun: I have a couple of complete episodes Fairy Princess Minky Momo: I've managed 4 raw episodes, including the famous one Magical Angel Creamy Mami: I may have missed out on this one altogether Nurse Angel Ririka SOS Geneshaft Najica Blitz Tactics Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha: hard to believe it can't be purchased new. Uta~Kata Okusama wa Maho Shojo Banner of the Stars 3 Mai-Otome Shion no Oh Chiko, Heiress of the Phantom Thief Given how many titles I already own, are still available in Oz or the US, or downloaded already, it could have been much worse. On to the real reason for this post. **** Beautiful Fighting Girl # 5: The great Lady of perfection, excellent in counsel, the great one, sacred image of her father aka... Cleopatra

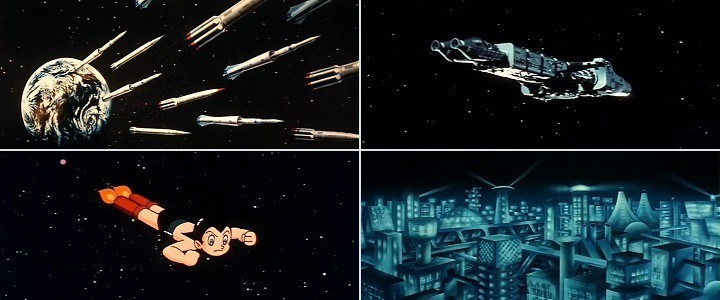

Cleopatra: space opera epic. No. Wait... Synopsis: Framed within a story involving interplanetary warfare and time travelling conscious minds, Cleopatra meets three great Roman generals - Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and Octavian (later known as Augustus Caesar). Following Julius Caesar's triumphal entry into Alexandria, rebels smuggle Cleopatra into his chambers in a sack to assassinate him. Instead the two become lovers. Caesar takes her to Rome where she remains until his assassination by Brutus and Cassius. Returning to Egypt she welcomes and seduces Mark Antony, who is subsquently defeated in battle against Octavian. When her attempts to ingratiate herself with Octavian fails, Cleopatra kills herself. Production details: Premiere: 5 September 1970 Source material: original production Studio: Mushi Pro Original plan & story line: Osamu Tezuka Directors: Osamu Tezuka & Eiichi Yamamoto Music: Isao Tomita Among the animators can be found Yoshiaki Kawajiri who would later direct Wicked City, Ninja Scroll, Birdy the Mighty, Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust and Highlander: the Search for Vengeance, among other things.

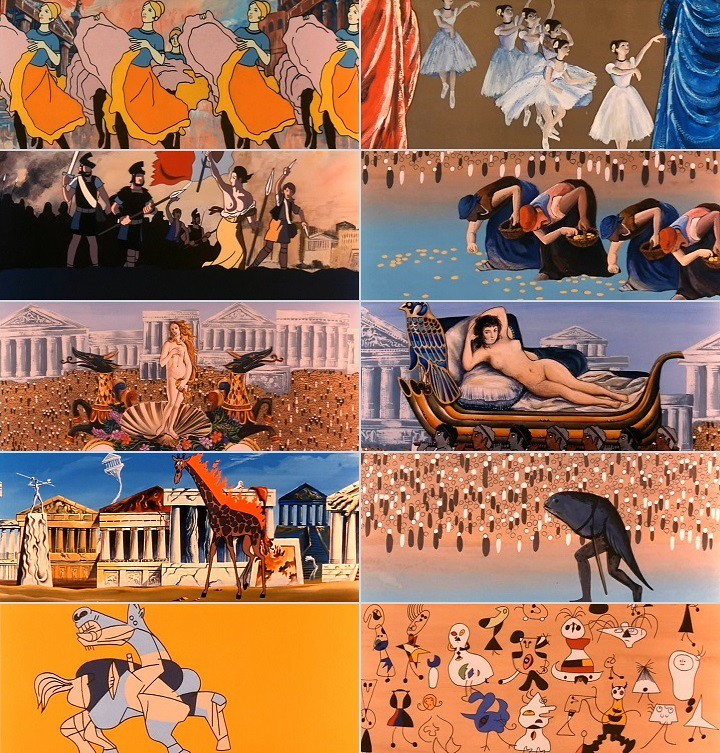

Cleopatra: incisive examination of Western history and culture. No. Wait... Background: In 1968 Osamu Tezuka stepped down as company directer at Mushi Pro to start a new company, Tezuka Productions. While his creative influence at Mushi remained profound, Mushi Pro was beginning to look to source material from elsewhere, such as the first Ashita no Joe series (reviewed here). Tezuka's previous film, Senya Ichiya Monogatari, had not recouped its costs, which forced Mushi to rely on Cleopatra to make them up. It also cut into the new film's budget, further disenchanting the staff, who, it seems, were unhappy with their working conditions. Cleopatra bombed. Mushi Pro was spiralling into bankruptcy. Comments: Tezuka and Yamamoto had always had a penchant for the absurd, clearly seen in the picaresque Senya Ichiya Monogatari, but given even more rein in Cleopatra, which is probably best viewed as a farce. Examining the framing story of the film gives a clue to what Tezuka and Yamamoto are perhaps trying to achieve. Placing the film within the context of its times provides further hints. The framing story is set far into the future. Earth is at war against Pasatorine (Pasateli according to some sources) rebels. One of the earth commanders discovers that the resistance is putting into place the mysterious "Cleopatra Plan", so he sends three agents back to the time of Cleopatra to uncover what the plan might entail. Turns out the Pasatorine rebels are taking the form of beautiful women in order to marry earth men, then using sex to kill them or, at the very least, distract them sufficiently to allow the Pasatorine to gain their freedom from their overlords. The ruse reflects the Egyptian rebels' scheme to use Cleopatra to rid themselves of the Romans. Cleopatra modifies the plan in the hope of using her charms to court influence with them. The framing narrative is a neat inversion of the Aristophanes comic play, Lysistrata, where the women of Greece, fed up with their husband's interminable warmongering and led by the eponymous heroine (whose name means army disbander), go on a sex strike until the men negotiate peace. Eventually, both the men and the women are so desperate for sex they reach a reconciliation and everyone lives happily ever after. Despite the narrative inversion, both the film and play humorously play on the notion found in the popular sixties and seventies slogan, make love, not war.

Cleopatra: postmodern pastiche of popular culture. No... Wait... That popular slogan should also remind us of the times in which the movie was made. In 1970 the Vietnam War was raging. At its peak over half a million American soldiers (and over seven thousand Australians) were deployed. The war spilled across borders as the US covertly began massive bombing campaigns in Laos and Cambodia. Protests grew around the world, while the Viet Cong's Tet Offensive convinced many that the American intervention was proving to be impotent. By the time the Mai Lai Massacre became public knowledge in 1969, any moral justification for the war was evaporating in the face of public opinion. The connection with the Vietnam War may seem tenous, but there are other elements pointing in that direction. In The Anime Encyclopaedia Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy are spot on when they describe the green-skinned Caesar "as a cigar-chomping American politico". Mark Antony could be straight out of a Hanna-Barbera cartoon. If Caesar represents American belligerence and Mark Antony American impotence, then Octavian is ambiguous, in more ways than one, though he reminds me of Spock from Star Trek. The film's emotional climax isn't Cleopatra's death. Rather, it's the next scene as Lybia, her handmaid, climbs to the top of a pyramid and exhorts the Roman troops below to get out of Egypt. Her "Get out!" echoes over and over. The end credits play to an American-style folksong that asks are we guerrillas or gorillas.

Cleopatra: breaking new ground in the girls with guns genre. No... Wait... (How the gun got into the scene isn't convincingly explained.) With the film sinking with hardly a trace when it was first released, its polemics are now arcane, unless the viewer can make the necessary associations. Those misled souls who watched it in 1972 at porno cinemas in America may have felt not only cheated - it's not pornographic - but, living at the time of the Vietnam War, also affronted by a one-time military enemy hectoring them, albeit slyly, about their nation's own hegemonic adventurism. Other problems also undermine the film. Foremost is Tezuka's seeming inability to treat anything or anybody seriously. His characters almost always have a comic edge to them. They are clowns to a person. As a result, when he is being serious, it isn't immediately apparent. I first watched the film not quite four years ago, but I'm finding it much more interesting this time around, simply because this review requires me to research and think about its themes. A more casual viewing is much less rewarding. The overall effect is to distance the viewer from the experience, leaving them less engaged than they might otherwise be. Visually, the film is both brilliant and awful. Sometimes it's gorgeous, other times its animation shortcuts or its figurative representations seem amateurish. There are scenes that surprise and amuse. I think of the eye-catching sleight of hand as the old woman and resistance leader Apollodoria folds up Cleopatra then inserts her into a sack. Caesars triumphal parade in Rome - see second group of images above - is emblematic of everything that is appealing about Tezuka and everything that is frustrating. With minimal animation and much repetition it, nevertheless, combines visual flair, clever gags and a jaunty theme to both capture the festive spirit and simultaneously skewer the pomposity. The scene is reminiscent of the poster sequence in his Tales from the Street Corner and the whole of Pictures at an Exhibition. I can't help but think that when he's short on ideas, Tezuka falls back on presenting a figurative parade of images. He has mastered activity without movement. That said, those segments are enormous fun. Tezuka and Yamamoto try to repeat the "pink" scene from Senya Ichiya Monogatari when Cleopatra and Caesar make love the first time, using evolving line drawings to express the eroticism. It doesn't work. The scene is worse than grotesque, which could have worked if done well. It's clumsy. Somewhat more successful, in its eroticism, but perplexing in its placement is the mirrored moving image sequence after the death of Mark Antony. Again, clumsy. Perhaps the message is that death is erotic. The framing sequence has animated heads on live-action bodies. So weird. Films should start with their best sequences, not their worst.

Cleopatra: coded anti-Vietnam War film. Possibly. (Actually, that's Lybia in the image.) Other oddities abound. Anime characters from the time pop up all over the place. Other, inappropriate images get dropped into a scene, sometimes literally. During the Battle of Actium a space re-entry capsule parachutes into the sea among the war galleys. The death of Caesar is presented as a Kabuki play, complete with traditional music and howling voices. It's clever and it's funny but it does go on and on. As the protagonist of the film Cleopatra is intentionally enigmatic. The viewer never gets inside her head. When she is transformed from an ugly girl to a beautiful queen (supposedly - I think her character design is sour) by the priest, she seems supportive of her peers' revolutionary aims, yet she willingly becomes the lover of both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. It's not even clear that she likes either of them. Her grief might well a manifestation of her fear for her future. My take is that she sets out to seduce the generals for political ends but is ensnared by her own nature and desires. As she says after the death of Antony, all she wants is love and the things that ordinary women have. I wonder if Tezuka had read The Feminine Mystique. Isao Tomita provides another worthwhile score for the Mushi canon. Centrepiece is his loveliest creation yet, the sad, yearning Tears of Cleopatra sung by Saori Yuki. The film uses multiple arrangements of the piece. One in particular is languid, fragile and wistful. In the love-making scene between Antony and Cleopatra, the tune is played on a sitar - such a fashionable instrument of the time (1970, not the 4th decade BCE). Without the tune the film would lose much of its feel and much of its lustre. Other pieces are workmanlike, without ever matching the haunting beauty of Cleopatra no Namida.

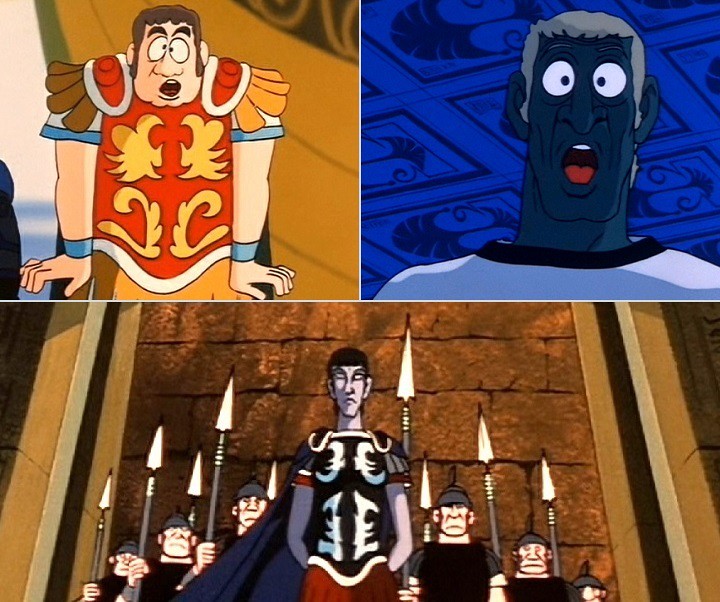

The Roman generals upon meeting Cleopatra. Clockwise from top left: Mark Antony; Julius Caesar; and Octavian - you just know he's going to be trouble. Rating: decent. Cleopatra tries to be several things at once: a tragi-comedy; an anti-war polemic, a character study, a cartoon for adults with unabashed erotica, a pastiche of popular culture and, above all, a vehicle for Tezuka's quirky humour. Because no single element is done outstandingly well, other than one song, and because there are so many elements then any possible impact it may have had becomes diffuse. It represents an interesting path that anime started down before turning back around. In one sense it has left a lasting legacy that was hinted at in Princess Knight. For the first time in anime we are presented with a sexualised female protagonist. With the magical girl genre now established, the obvious next step is to combine the two. Unsurprisingly, Tezuka will be in the vanguard. Resources: ANN Cleopatra @ tezukaosamu Cleopatra @ Cartoon Research The Font of all Knowledge Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade, Volume 2, Jonathon Clement, A-Net Digital LLC The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle

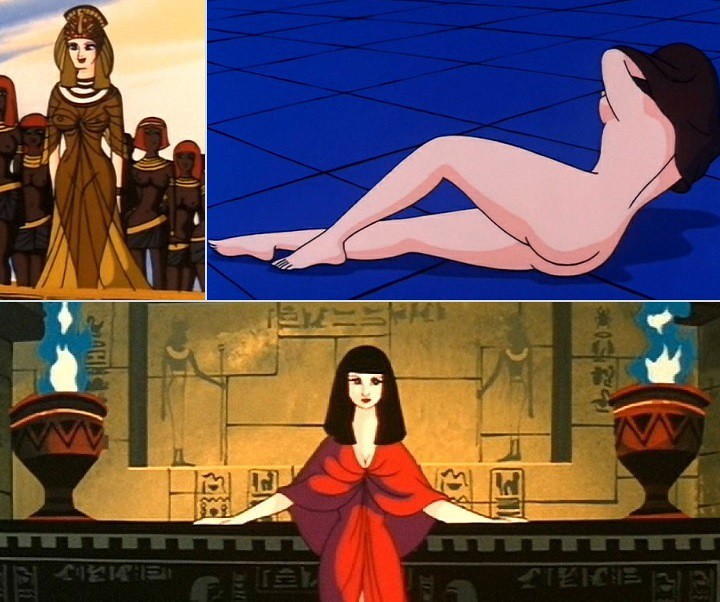

What the generals saw. Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:32 pm; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl # 6: Mako Urashima

Mahou no Mako-chan (ie, Magical Mako-chan) (Episodes 1 (part), 2-5, 10-13, 43-45 & 48) Synopsis: Bored with her life as a mermaid, the youngest daughter of the Dragon King wishes to become human after saving then falling in love with a young man from a sinking ship. Her wish is granted, however she can never return to the life of a mermaid. Adopted by a kindly old man who shares his house with a menagerie of animals, she goes to school, makes new friends and overcomes ordeals. All the while her parents keep watch over her. Following her abduction early in the series, Mako's father gives her a protective magical pendant with reality altering powers. Mako wonders if she will ever be re-united with the young man she saved. Production details: Premiere: 2 November 1970 Studio: Toei Doga Source material: original production Original creator and planner: Kenji Yokoyama under the name of Shinobu Urakawa Series director: Yugo Serigawa Music: Takeo Watanabe Comments: The first thing that I need to mention is the peculiar form the episodes that I watched took. Unable to locate any fansubs, I eventually tracked down multiple rarely-viewed episodes on Youtube under its Polish name, Sirenka Mako. Catch is, not only were there no subtitles, but the Japanese dialogue was overlaid with a Polish commentary. Hey, if I must have one language I can't understand then I may as well have two. Simultaneously. So I'll make the same caveat I did with Himitsu no Akko-chan: this is more an impression than a review. More so, actually. Having a greater personal dramatic focus than its predecessor it must rely more on dialogue, which made it harder for me to follow. The female Polish commentary was precisely enunciated, in a cultured, well-educated voice. It seemed too good for the vaguely disreputable anime antics on the screen. I mean, imagine an elegant society lady describing anime fanservice. Maybe she was admonishing the Japanese for their capitalist pigdog depravity - this is 1970 communist Poland after all? I wouldn't know. This is yet another example of an early anime with a female protagonist that was released in countries all around the world - other than the Anglophone parts, that is. You can find snippets on Youtube in French, Italian, Spanish and, of course, Polish, but not in English. As I said earlier, no one has fansubbed it. I shall desist from railing against Anglophone misogyny lest I find myself hoist upon my own petard at some point. I'll just say it's frustrating. Not only is this an emotion friendly take on The Little Mermaid story but Mako-chan shares elements with her two Toei predecessors from Sally the Witch and Himitsu no Akko-chan. Like Sally, Mako comes from a magical world although, being human now, she no longer has any innate magical powers. This is more than compensated by the stupendous magical pendant her father gives her. The pendant is an analogue of Akko's compact, although Mako doesn't often use it to transform herself. Instead she can and does use it to alter reality in many ways, such as creating objects out of thin air, stopping speeding vehicles or removing the pollution from entire landscapes. The pendant is so powerful that it removes any tension that the anime may have otherwise generated. I constantly found myself growing impatient during perilous moments, waiting for the pendant to be brought out. The show tries to counter the problem by having Mako's father admonishing her for over-using it, or even reversing the changes. He would rather Mako resolve issues on her own. Mako tries to follow his advice, but what's a girl to do when she is abbucted, or dangling from a cliff, or about to be assaulted? In a further nod to the older series the Hanamura triplets are replaced by twins Jiro and Taro, who get up to mischief, but not as entertainingly as their earlier counterparts.

Clockwise from top left: If only Homura Akemi could get hold of that pendant. It would solve all her problems Cop Mako-chan's cthulhu eyes The lingerie scene That mini-skirt Mako-chan and her gang Brandishing a sword at twins Jiro and Taro Befuddling her father the Dragon King As mermaid before having her wish granted. A development, so to speak, from the earlier Toei magical girls is that Mako appears older and is drawn more realistically and elaborately than either Sally or Akko-chan. She looks sixteen to their thirteen. Strangely, though, her classmates, with one notable exception in her rival Tomiko, look like they belong in primary school. Mako's best friend, Haruka, is half her size. Several of the male peers she encounters also look and behave her apparent age, while the two male members of her gang look way to young to associate with her. I suppose it depends on whether the character's role is to create sexual tension or comic relief. It does leave me wondering what the age is of the intended adience. On a related note, though it seems rather mild after watching Cleopatra, Mahou no Mako-chan increases the level of fanservice for a shoujo magical girl TV series. It is more frequent and more eroticised, while the heroine is now aware of her allure. In one episode she spends the day with her father, who is in human form. In quick succession she teases him in her lingerie (TV tropes labels it as anime's Lingerie Scene trope codifier), followed by undressing in his proximity - she waves her bra at him - and later in a fashion store where she buys a mini skirt that doesn't cover her underwear. Don't get me wrong: the fanservice is mild by today's standards, while things will be ramped up further very soon. Again it leaves me wondering who the fanservice is for. Were men watching this show back then? It is a sign, perhaps, of how the female protagonist for a male audience evolved from the magical girl. Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind is the love child of Sally the Witch. Two trends in the three Toei series are diminishing slapstick and increased seriousness. Hence, Sally the Witch is the most fun of the three series. Mako has comic moments but the dilemmas she faces are urgent and sometimes dangerous. Flirting aside, she doesn't have much of a sense of humour. She is usually the observer or the voice of reason when everyone else is losing their heads. She's the straight guy surrounded by clowns - likeable, admirable but too dull to be lovable. Give me Yoshiko from Sally the Witch or Princess Knight any day.

The serious tone allows Mahou no Mako-chan to broach some serious topics. In one episode Mako visits a heavily polluted bay where an old fisherman laments the destruction of a way of life. All around chemical factories pour their poisonous by-products into the bay and foul the air with their emissions. Mako joins a protest to bring to account the owner of one of the factories that has so destroyed the environment. By the end of the episode the issue remains unresolved and the fisherman dies of a broken heart. This is another fascinating example of anime reflecting its times. The episode is referencing the mercury poisoning that afflicted the residents of Minimata who ate fish from their bay that had been contaminated with mercury waste from the Chisso chemical factory. After a decade of cover-up the Japanese government belatedly admitted in 1969 (remember, the anime premiered in late 1970) the cause of the disease. The admission was explosive, leading to protests, litigation and intimidation - not forgetting the misery of the afflicted families. While the anime pulls its punches - it doesn't show anyone suffering the deformations of Minimata disease - it clearly condemns the chemical factories at a time when the public wasn't altogether sympathetic towards the victims. It's the best of the twelve and a bit episodes I saw. Most of the others were dull, particularly to my linguistically challenged ears. Rating: Not really good. Mahou no Mako-chan doesn't added much to the development of the magical girl. The protagonist is a little older, the magic is a conflation of elements from the earlier two Toei series, the subject matter is more serious (and less fun), and fanservice is introduced into the mix. I wouldn't recommend it unless, like me, you are obsessively exploring the roots of contemporary anime. Sources: ANN The font of all knowledge TV tropes Beautiful Fighting Girl, Tamaki Saito, trans J Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson, University of Minnesota Press The Anime Encyclopaedia, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle **** It will be at least two weeks before my next review. I've pretty much blown my data limits for both my PC and my mobile phone for the month. Last edited by Errinundra on Thu Feb 08, 2024 5:42 am; edited 3 times in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Kuroi Kikori to Shiroi Kikori (ie, the Black Woodcutter and the White Woodcutter)

Reason for watching: My original plan was to review Marvellous Melmo next after Cleopatra. I had been furiously downloading material the previous internet billing month, but I did manage to have the Mushi Pro magical girl series downloaded and 60% viewed when I discovered Mahou no Mako-chan (with its Polish voice-over) and all 26 episodes of the groundbreaking Sarusai no Taiyou (with a French dub) buried in the far recesses of Youtube. As both were released before Melmo they became my priority. You can see my review of Mako-Chan above, but I only got to episode 10 of SnT before I reached my download limit for the month. The new month began two days ago (as I write this), which hasn't been enough time to complete and review it. Rather than miss two weeks I cast around for something short to review in its place and found this gem from 1956. It's only fifteen minutes long and doesn't have a female protagonist, but there is a link to the great project. Production details: Vintage: July 1956 Studio: Nichido Eigasha (ie, Nichido Films) and Kyoiku Eiga Haikyuusha (ie, Educational Film Distribution) Director: Taiji Yabushita Key Animation: Yasuji Mori Source material: Hirosuke Hamada, a contemporary of Kenji Miyazawa who is similarly revered as an author of children's books. Background: Nippon Doga/Nichido was set up in 1947 by veteran animator Sanae Yamamato and included such luminaries as Kenzo Masaoka (Kumo no Tulip), Taiji Yabushita (who would go on to direct Tale of the White Serpent) and Yasuji Mori, whose influence on anime has been described by Isao Takahata as "incalculable". The 1950s were a lean time for Japanese animation. To give some idea, Kuroi Kikori to Shiroi Kikori was the only anime produced in 1956 according to the ANN encyclopaedia, though Wikipedia also mentions Yuurei-sen, a cutout and silhouette animation from another veteran, Noburo Ofuji. Nichido made ten two reel films and one single reel film over eight years in a hut on the grounds of a girls' school. The studio became a subsidiary of Toei Films in 1956, then re-badged as Toei Doga the following year, with Taiji Yabushita becoming Director of Production. He would go on to direct or co-direct most of the Toei's early anime productions before eventually becoming a teacher. He would also become the author of animation textbooks. Synopsis: On a winter's night a bear, a fox and a squirrel seek refuge from the cold. They are drawn to the hearths in the homes of two woodcutters. One man treats them poorly, while the other welcomes them. (I plagiarised myself again!)

Comments: I have said in the past that my life covers all full-colour anime. In the last few days I've discovered that I'm not quite that old, if that makes sense. The Black Woodcutter and the White Woodcutter beats me by about a year and a half. I wouldn't be surprised if I learned that it had been produced after Toei's purchase of Nichida, given the stylistic parallels between this short film and the early Toei feature films (reviewed elsewhere in this thread) and the relatively high production values when compared with older anime I've seen. Then again, given that the same creative talents were at the core of Toei Doga, then it's natural that some sort of direct lineage would be apparent. One thing I've learnt in the last year or so is how much we owe Toei for the art form that gives us so much pleasure. With its rustic setting, supernatural elements and heavy-handed moral lesson, this could be straight out of the sixty years younger Folk Tales from Japan. Yep - the nasty woodcutter has no-one to help him in his moment of mortal danger, while the kind-hearted woodcutter is saved thanks to his collaborative efforts with his newly acquired animal friends. Lovingkindness and communal endeavour will be rewarded, while avarice and individualism will be punished. It's so Japanese, so ideal and so naive. I like it. In terms of artwork and animation, the film is more sophisticated than Folk Tales, despite the six decades age difference. The colours are softer, though still surprisingly bright, given the film's age. Unlike the newer series it's actually animated. As with Yabushita's Toei flims, much of the character animation seems too slow, as if the characters are acting in something more viscous than ordinary air, like clear treacle. Things come alive when the black woodcutter chases the squirrel through the snow. The sequence combines dynamic moves with simple but effective visual gags. The appearance and movements of the ice witch are more stilted, less convincing. This is speculation, but given the up-front advocacy of traditional Japanese values along with the name of Nichida's co-producers - Educational Film Distribution - I wonder if the intention was to screen the film in schools. If so, it follows the common Japanese tendency of combining puerile elements, such as the almost infantile character of the squirrel, with unglossed violence, such as the shooting scenes, which are played seriously. This isn't the eros and thanatos that will become a staple of anime. It's innocence and death, presented surprisingly starkly. In any case, if Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy are anything to go by, the film mustn't have made much of an impact. Neither of their books mention the film (though they are useful for information on the studios and their prime movers). The animals are appealing in a pitiable way, rather than through the singing, dancing, and jolly slapstick we get in the subsequent Toei feature films. Other than the fox's awkward two-legged gait and the squirrel's contrived cuteness, that's a good thing. There are no spoken parts and other sounds are muted, as if deadened by the enveloping snow. The music is likewise understated but effective. Overall the film has a brooding, yet oddly graceful air to it. The quality of the print on display is remarkably good, being sharp, steady and devoid of the marks and faults often seen in older celluloid films.

Rating: Decent. At only fifteen minutes, this is well worth the effort in tracking down. Resources: ANN The Font of all Knowledge - clearly not so, as I also had to consult... The Font of all Knowledge German edition translated by Google Anime: A History, Jonathon Clements, Palgrave MacMillan via Kindle The Anime Encyclopaedia 3rd Revised Edition: A Century of Japanese Animation, Jonathon Clements and Helen McCarthy, Stone Bridge Press via Kindle AniPages Last edited by Errinundra on Sat Mar 03, 2018 8:35 pm; edited 1 time in total |

|||

|

|||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

||

|

Beautiful Fighting Girl #7: Nozomi Mine

Sasurai no Taiyou (aka Wandering Sun) Spoiler alert. Wandering Sun depends on melodramatic developments to give the story impetus. Being a story with a moral, the discourse flows from these central dramas, so discussion of the anime's themes will necessarily involve some spoilers. Synopsis: A disgruntled nurse switches the name tags of two baby girls: one - Nozomi - will become the daughter of an impoverished couple living in Tokyo's slums; the other - Miki - will become the daughter of fabulously wealthy parents. Though their prospects have now been reversed, they will meet in high school and become rivals as up-and-coming pop singers in Japan's cutthroat entertainment industry. Miki - living a pampered life - will get unstinting support from her supposed parents, while Nozomi will suffer setback after setback in her personal circumstances as she struggles to make a name for herself in the provinces and the lowlife bars of Tokyo. Envious of Nozomi's singing talents, Miki uses every opportunity she can to humiliate her rival. Whatever they do, however, the reputation and prospects of the two young women hangs on the whim of a nurse with an axe to grind, Michiko Nohara.

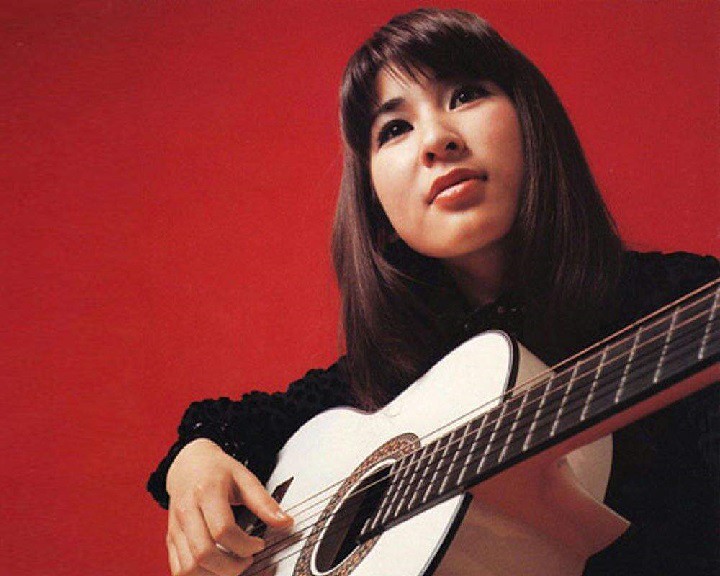

Nozomi: trawling the bars of Tokyo for work. Production details: Premiere: 08 April 1971 Studio: Mushi Pro (Mushi: first with idol singers) Source material: Sasurai no Taiyou, written by Keisuke Fujiwara (Fujikawa in some sources), illustrated by Mayumi Suzuki, published by Shojo Comic from August 1970 to August 1971. Series Director: Chikao Katsui Director: Katsumi Hando Storyboard: Yoshiyuki Tomino Character Design: Yoshikazu Yasuhiko (The last two named will collaborate on Space Battleship Yamato and Gundam.) Junko Fujiyama, aka Keiko Fuji: Wandering Sun set an example for future anime and music industry collaborations. The seiyuu chosen for the role of Nozomi Mine was Enka singer Keiko Fuji. The revival of modern Enka - a form of sentimental ballad - is generally put down to Fuji's debut in 1969. Participation in Wandering Sun was part of her strategy to gain wider exposure in the Japanese market. Her debut album, released five weeks prior to the premiere of Wandering Sun, was number one on the Oricon charts for 20 weeks - a record that still stands. It was finally replaced at the top of the charts by her follow-up album, which held the position for a further 17 weeks.

Keiko Fuji: wholesome and folky. Comments: Only the first episode has an English language fansub. I tracked down the rest of it in the dark recesses of Youtube - dubbed in French - and in my madness watched all 26 episodes. That my knowledge of French exceeds my knowledge of Polish means little. It's about on par with my Japanese, which left me reliant on visual cues, outside sources and the occasional understood word. I was often floundering. Again, consider this post an impression, rather than a review. Despite their problems, Mushi Pro had had some success with Ashita no Joe, premiered a year previously and still running as Wandering Sun began. Toei's magical girl shows had proven that a female audience was there to be catered to, so it might have seemed obvious to the Mushi Pro decision makers that the next step was a shojo equivalent to the famous boxing anime. Wandering Sun has all the hallmarks of Ashita no Joe, but with the fights replaced by pop music and the macho posturing replaced by personal drama. Yoshiyuki Tomino storyboared both series, thus providing some continuity in personnel. Beyond that they share a similar look, working-class ethos and a glimpse of Japan moving from post-war poverty to industrialised wealth. What Wandering Sun lacks is the talents of Osamu Dezaki (the other Osamu), who used Mushi Pro's dwindling resources masterfully in Ashita no Joe. Production-wise, Wandering Sun is miserly fare, probably exacerbated by the language hurdles in my way. I was left gazing at poorly drawn characters not doing very much in featureless settings. Had I understood the speech I mightn't be so critical of the visuals: a good script can cover poor production. It didn't help that the two main characters each had a signature song that they sang over, and over, and over, and over... Wandering Sun is an anime with a thesis and a moral. Contrasting two different families it valorises the efforts of everyday working Japanese, critiques the privileges of the wealthy and highlights the emptiness and dishonesty of the entertainment industry (without actually condemning it - after all, anime is part and parcel of it). How well the two young women cope will largely be determined by their place in and relationship to their families. It isn't until episode 24 that the anime discloses the nurse's motivation. spoiler[During World War 2 she had nursed, then fallen in love with an injured soldier. He subsequently jilted her to marry an heiress to a large fortune - the two becoming the wealthy parents of the anime. By switching babies, she ensures that his child is deprived of the benefits of his feckless marriage]. The anime is arguing that your lineage is less important than the social environent in which you are raised. A sheltered upbringing in a loveless family is no match for the rigours of a slum life, moderated by a supportive family. (Mind you, a eugenist might turn that around by saying that Nozomi had the advantage of better genetic stock, while Miki was doomed by her lower class genes.) Wandering Sun's argument is the antithesis of that in George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion - better known as the musical My Fair Lady - which posits that even the snottiest working-class girl can be turned into a ballroom countess with the right amount of training. Wandering Sun argues that character can only be developed through enduring setbacks and belonging to a community. Again, the old Japanese saws raise themselves for our consideration. It follows that poor Nozomi must endure indignity piled upon misfortune. Her mother is going blind, her father - who makes a living selling noodles from a handcart - is attacked by thugs, leaving him an invalid. At the worst possible moments Nozomi's voice fails her (suggesting she may be consumptive). Unable to support the family through her singing, she takes on part time jobs working as a maid for a songwriter who just happens to be Miki's singing teacher. She also works for Miki as her personal assistant during the latter's public appearances. Miki uses these opportunities to humiliate her rival. There is an important subplot where Nozomi falls in love with Fani, a champion boxer in the making. (This allows Mushi to re-use stock material - some of it looks supsiciously like touched up footage of Joe, Rikiishi and other boxers from Ashita no Joe.) Being adopted at birth, he doesn't know his real parents. When he learns early on, from the scheming nurse, that they are, in fact, Nozomi's parents, he flees Japan to preserve her honour, leaving Nozomi, who just can't take a trick, utterly bewildered. The cruelty is that we know that they aren't really her parents. Much of the pleasure of the show is in the viewer knowing more than the players. Michiko judiciously provides snippets of information to the characters to cause as much confusion as possible. Never underestimate the brooding perfidy of a person jilted.

Miki Koda (left) and Nozomi Mine: their costumes and bearing suggest artifice and authenticity. Getting back to Nozomi - as with Joe Yabuki she is the anime face of a growing, confident Japan rediscovering its identity and leaving behind the disaster of the war. Joe's belligerence won't do in a shojo series so it's replaced by a cheery optimism. The challenge for the Mushi team is to maintain that cheer in the face of all Nozomi's setbacks. Other than a couple of big dramatic moments such as Fani sailing from Japan, she doesn't moan or groan, or curse her bad fortune. Nor does she become cynical or despondent. Her characteristic reaction is a surprised intake of breath. Deaf to the verbal cues I suppose this sort of sound became more noticeable for me. The surprise reassures us that she has maintained her optimism while simultaneously registering that the circumstances run counter to he view of the how the world should be. Catch is, she does it multiple times in some episodes. Did Mushi record it just once? Or was it recorded freshly each time it was needed? It become, for me, her signature catchcry. Nozomi is the epitome of authenticity. She is a genuinely talented singer and guitarist who plays to her talents. She sings conservative ballads, dresses demurely, thinks and behaves guilessly and makes rapid connections with ordinary people. It follows that her progress will come from her innate qualities. Miki will, in a sense, have a harder time of it. She's a schemer - helped by her equally scheming rich "mother" - she's cruel, determined to become a pop singer despite her limited singing abilities. She depends on the lie behind her position in life to advance. She sings pop to Nozomi's folk and dresses to tease. For much of the series her star rises more quickly than Nozomi's. But Michiko is waiting and brooding in the wings to bring the whole artifice crashing down. Odd thing is, Miki is a gifted piano player. The anime seems to be saying that to be authentic you must play to your true nature. The men of the tale are intriguing. No doubt magnified by Nozomi's naivete, they are uniformly threatening. The are tall, unsympathetic, older, experienced, ambitious and cunning. Some of them even have a sleazy look to them. (To quote Jessica Rabbit, "I'm not bad. I'm just drawn that way.") Part of the pleasure of the series is the realisation that the story isn't about the innocent girl who loses her soul in the music industry; that Nozomi isn't going to be molested or assaulted. There are some bad men, such as the manager on the dismal tour of the provinces, who forces his musicians to play in wretched conditions, for miserable pay, even when they are ill. On the other hand there's her kindly uncle (I think that's his relationship to her) who is the one person who goes out of his way to help her throughout the series; there's a trumpet player on that ill-fated tour who starts by mocking her abilities and inexperience, but learns to appreciate her talents and opens her ears to the joys of ensemble playing. My favourite is the stern, chain-smoking, fop-haired music teacher and composer who bullies Nozomi as his way of bringing out the best in her. He perserveres with Miki because he is paid well to. One of the best moments in the series involves another of the male characters. In episode two Miki invites Nozomi to her birthday party - remember it's a date they share - to rub in the advantages of her family's wealth. At one point Nozomi dances a waltz with Miki's emotionally estranged father. Nozomi and he get along immediately: dancing fluidly and relating naturally. In truth, it's father and daughter arm in arm and face to face for the first time in their lives, though they don't know it. For most of the series it's that omniscient viewer privilige that provides the major pleasure.