Forum - View topicErrinundra's Beautiful Fighting Girl #133: Taiman Blues: Ladies' Chapter - Mayumi

|

Goto page Previous Next |

| Author | Message | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

My first recently completed series to be considered in this thread. Hey, the two seasons have a combined 126 episodes. It has taken me a while to get through them.

Ashita no Joe and Ashita no Joe 2; aka Tomorrow's Joe Reason for watching: Part of my project to watch significant titles from last century. Synopsis: Ashita no Joe (broadcast 1970-71): Follows the early boxing career of Joe Yabuki, a delinquent and drifter, whose brawling impresses down-and-out former boxer Danpei Tange. While incarcerated in a youth detention centre Joe meets soul-mate and future boxing rival Tohru Rikiishi who becomes his inspiration. On release from prison Joe trains with Danpei in a shack on the banks of the Sumida River in the corrugated iron slums of San'ya in Tokyo. Motivated by Danpei and Rikiishi and supported behind the scenes by the young heiress pilanthropist and boxing manager, Yoko Shiraki, Joe hones his skills. He rises in the Japanese rankings until a long anticipated bout ends in tragedy, leaving Joe devastated and without his boxing mojo. Yoko brings the like-minded free spirit, Carlos Rivera, from Venezuela to Japan to rekindle Joe's killer instincts, culminating in a full-on slugfest. Ashita no Joe 2 (broadcast ten years later): Retraces the final episodes of the original series from when Joe kills his oponent in the ring and has is enthusiasm for fighting re-ignited by Carlos, then follows his upward progress until he finally meets the world champion Jose Mendoza from Mexico. On the way Joe must overcome a malaise that grows with his abilities (again remedied by Yoko finding the appropriate opponent) and also come to terms with advancing punch-drunk syndrome.

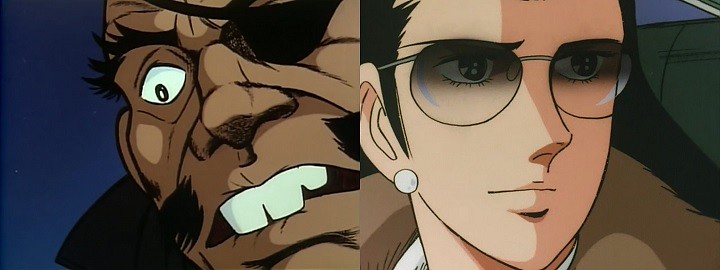

Danpei Tange and Yoko Shiraki. Note the stylistic difference between the older and newer series. Context: Given that, for me, the most interesting things about Ashita no Joe are its historical and social settings I'd like to give some personal context about the times in which it is set. As a child in the 60s and a teenager in the 70s, Japan loomed large in Australia, probably only exceeded by the US and UK in terms of impact. Within a generation of being vanquished in World War 2 - pretty well every city had been razed - Japan was touted as an economic miracle. Toyota and other car companies had devastated the motor industry worldwide; Honda had done the same for motorcycles; and the Japanese exploitation of the transistor had revolutionised household appliances. There was a joke at the time that Japan lost the war but won the peace. Japan exuded a confidence akin to what can be seen in China today. (Mind you, I also remember news reports about the pollution in Japanese cities and also the violent protests over the building of Narita Airport.) It even got to the point where economic pundits were saying that Japan's GDP would inevitably exceed America's. Reality intervened, however, and the 1970s oil shocks and resulting stagflation saw investment in Japan move to real estate, eventually resulting in a massive property bubble. It's hard to imagine those heady times when you consider how introspective and directionless Japan seems to be today. On a more particular level, at that time the face of Japan became, for Australians, a game boxer named Fighting Harada. In the space of two years he had three world championship bouts with Australian boxers: once for the bantamweight crown with the aboriginal Lionel Rose (who, incidentally, became Australian of the Year after the fight) and twice for the featherweight title against Johnny Famechon. All three boxers were highly skilled. Harada was short and stocky with an appealing, childlike, quizzical look on his face. His fighting style put more value on courage than strategy. I remember my stepfather listening to two of the bouts live on the radio while (technological marvel of marvels) the second Famechon fight was broadcast on live TV in glorious black and white. (Note that Melbourne is one hour ahead of Tokyo). I viewed the fight recently on the web and, Famechon being knocked down late in the fight - it was ruled a slip by the referee - then hitting Harada through the ropes and out of the ring, brought back memories from that time. Harada first become a world champion in 1962 and it is highly likely that he was an inspiration for the original manga.

Joe Yabuki, in characteristic red and white. Comments: I'll get it out of the way right now: Joe Yabuki is a prick. He's loud, provocative, in your face, arrogant and totally self-absorbed. Danpei is taken not only by the strength of Joe's punch but also the ferocious glint in his eyes (bitterly ironic when PDS later affects his eyesight). A boxer can only succeed if he remorselessly cruel. Yoko falls for his animal aura. Both Rikiishi and Carlos see a kindred spirit. Ego is an essential element in the make up of the three boxers but more more important is how they light up in the ring, how they blaze with life. Joe describes to Noriko, a young woman who is sweet on him, how his aim is to burn so brightly that not even charcoal remains, only white ash. When Yoko pleads with him not to face Jose because of his PDS, Joe says:

Yet Joe carries people with him. His intuitive enthusiasm, his larger-than-life force, his will makes him a charismatic figure to his professional entourage, his rivals, the slum-dwellers - particularly the children (after all, he is a child who never grew up) - and Japanese boxing fans. He shocks people then wins them over; they come to love him and follow him. A large part of the success of the show is how convincingly it portrays this dynamic. Another is how, the first series in particular, we witness the making of character from delinquency and confusion to orientation and involvement. His wild beast isn't so much tamed as directed. He begins the first series with a characteristic defensive stooped gait but under Danpei's guidance will come to walk straight and tall. His back becomes broader as the story progresses. His rivals are also magnetic, especially Rikiishi and to a lesser extent Jose. Another of the reasons why I rate the first series slightly higher, despite its lower technical merits and inferior conclusion, is that no rival in the second season, including Jose, can match Rikiishi. He is an older, simpler, wiser version of Joe. His crooked smile and gleeful enjoyment of fighting make him instantly likeable. Whenever Joe becomes too annoying Rikiishi can be relied upon to stitch him up. How his final bout with Joe is treated, how it concludes and how the aftermath is presented is shocking yet intelligently and movingly crafted. Jose, the fearsome world champion, is by comparison something of a cipher. He is the perfect boxer with no apparent shortcomings; the ultimate hurdle for Joe to overcome. Therein lies another difference between the two series: the first is more of a character piece; the second a more typical sports anime. I will say this, though - the fight with Jose, which occupies the last three episodes of the second series, ends magnificently. The last image shows friends, fans and foes standing in the stadium as one in awe. It's pretty good.

Joe and Tohru Rikiishi. Don't worry. They're wearing boxing shorts. I spluttered first time. Unless the plot requires otherwise (ie, blue denim prison uniforms), Joe is characteristically shown dressed in red and white. The inference is obvious and, by all accounts, Japanese fans at the time saw Joe as symbolic of the rising economic power of Japan. Director Osamu Dezaki cannily depicts this growth without ever drawing particular attention to it. Over the course of the two series the wastelands across the river are filled with ever larger and larger factories. Skyscrapers steadily get taller. The slum-dwellers start off watching Joe's bouts by gathering around TVs in appliance shop windows; later they meet in the house of someone who has a TV; by the end they can afford seats in the stadium. The boats plying the river become ships. Freeways appear. Cars become more and more common. Those that rich girl Yoko drives get flashier and flashier. The local grocery eventually replaces bicycle deliveries with van deliveries. The Tange Gym starts off as a shack under a bridge across the Sumida River and ends up a two story structure atop the embankment. As Joe's power grows, so does Japan's. (The only thing that doesn't change are Joe's most loyal fans - five street kids, who provide a Greek Chorus style commentary on events as well as comic relief. The story probably covers several years of Joe's life but they don't grow up at all. They can be amusing; they can also be tiresome.) Dezaki's working-class sympathies are obvious without being didactic.

Dere dere and tsun tsun in 1970, decades before they became fashionable. That's street urchin Sachi. She'll fleece you in a flash and clobber you with little provocation. I enjoy Dezaki's style. For all the melodrama, the corniness and animation cheap tricks, his timing and visual sense are spot on. Despite the limited animation his scenes can be eye-candy or bone-crunchingly effective. I see his influence in later directors, including Ikuhara and Mashimo. He also treats momentous events in his stories with finesse. The climaxes to Joe's fights with Rikiishi and Jose are both done superbly. For sure, they're over the top but it works with boxing, a melodratic sport if ever there was one. Mind you, by the time I got to the second series I'd had enough of the brutality of the fighting, melodramatic or not. I'd had my fill of grimaces, grunts, screams, distorted faces, stomach punches, blood, sweat, saliva, broken jaws, cracked skulls and punch-drunk syndrome. I guess that means Ashita no Joe got its message across successfuly. Anyway, I intend to watch more of Dezaki's anime if I can. It's worth reading Mike Toole's article, Dezaki's Due. And also Justin Sevakis's Buried Treasure article. Rating: Ashita no Joe = very good; Ashita no Joe 2 = good.

Joe and Jose Mendoza. A mild example of the brutality on display. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 13, 2019 3:49 am; edited 1 time in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

To my disappointment, the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF) didn't show any anime this year. To make up for this omission my next review celebrates the 2007 MIFF, which led to my anime renaissance.

Paprika Reason for watching: Back in September 2005 my nephew and his mother (my sister) invited me to see Howl's Moving Castle with them at the Nova Cinema in Carlton (an inner Melbourne suburb). It was only the second anime I had seen since my childhood (the other being the execrable Urotsukidoji: Legend of the Overlord about 15 years earlier.) I repaid the treat in June 2007 with Tales from Earthsea at the Kino Cinema in the city. While I enjoyed both moderately (slightly preferring Earthsea), neither awakened within me a passion for the art form. Julie, a cinefile friend of mine and member of MIFF, hearing of my apparent anime interest, took me to the MIFF Paprika screening at the amazing Capitol Cinema on 10 August 2007. In the space of the one minute and fifty seconds of the opening credits I became an unreconstructable anime fan. While I've had more memorable cinema experiences, they have all involved activities other than the actual watching of films. Happily, the rest of the film delivered on the OP's promise. Never before had I seen something that so successfully exploited the possiblities of 2D animation. Synopsis: At a psychiatric institution in Japan two wunderkinds - Dr Atsuka Chiba (a psychologist) and Dr Kosaku Tokita (an electronics developer) - build a psychotherapy machine that records dreams. Its power is enhanced by their subsequent invention of the DC Mini, a device that can remotely access dreams, both to record them and to insert new elements, including the avatars of the therapists, allowing them to participate in the dreams. When several devices are stolen, Chiba, along with her dream avatar, Paprika, must dive into society's subconcious to prevent the "dream terrorist" from breaking down the barriers between dreams and reality, especially when it becomes clear that the terrorist's dream can even infect people who are awake.

As in Millennium Actress a reflection reveals another, different self. Dr Atsuko Chiba and her dream avatar Paprika. Comments: To be in the audience of a storyteller is akin to being in a dream. We know it isn't real, that the wonders and alarms are artificial, that the logic may not be linear, or may not even make sense. Yet we suspend our disbelief - unwillingly in dreams and (mostly) willingly in cinema. More than in any other cinematic form we allow 2D animation to play with our sense of reality; and it is Satoshi Kon, more than any other director, who uses that freedom to confound and astonish us. In Paprika he explores dreams with 2D animation, to play with the paradigms of storytelling. It is a thoroughly postmodern text (if you can excuse the pomo talk) but it succeeds because it is so beguiling. Watching Paprika hop on a rocket painted on the side of a truck then fly through the nightime Tokyo metropolis, then step out of a computer screen to wrap a jacket around a sleeping animator, then stop the traffic with a snap of her fingers, is pure magic and pure Satoshi Kon. Tokita puts it nicely:

Only in animation will the viewer accept someone jumping into a television screen and coming out of a camera lens. Even with CGI we still place limitations on what we will accept. This makes animation potentially the most productive medium for tearing apart story telling structures, something understood long ago with Warner Brothers' amazing Duck Amok. Sadly, this potential has rarely been realised. Paprika is its apotheosis, a game being played at the expense of normal story telling conventions.

Paprika is an animation leap of faith from the mundane to the fantastic. The principal device of Paprika is that Satoshi Kon deliberately misleads the viewer as to what waking state the characters of the story are experiencing. First, by having them dreaming, and thus believing, they are awake. He then complicates things by allowing some characters to interact within shared lucid dreams. (If I hit you in our shared lucid dream am guilty of assault? If I rape you in our shared lucid dream have I committed a crime?) Finally he has the population of Tokyo share the same dream while they are actually awake; believing in and acting out the experiences of the dream. A row of men gleefully dropping off the side of a skyscraper in an orderly progression is just one of the film's memorable sequences. Instability prevails. For the players and for the audience. On a first watch there is little prospect of the viewer recognising the moments of directorial deception to avoid being bamboozled by events on screen. If you can’t tell what’s going on by two thirds way through… well, that’s the point. Don’t worry, though. The film is so entertaining, you only need to relax and let it play with your brain. As one critic put it, this is a film to be experienced, rather than understood. The instability created allows Satoshi Kon to incorporate a series of metafictional gags that work beautifully in the Japanese dub but, by their very nature, aren't nearly as effective in the American dub. This is because, in the Japanese dub, two important supporting characters - the barmen Mr Jinnai and Mr Kuga - are voiced by Satoshi Kon and the author of the original novel on which the anime is based, Yasutaka Tsutsui. They are not-quite-detached observers, but knowing who they really (?) are is central to the gag, which includes an outrageous plot hole that is, literally, a hole. It appears without explanation; the chairman of the research institute enters the hole as a cripple and comes out as a god, again without any explanation. He's then swallowed whole by Paprika, also without any explanation, and Tokyo carries on normal life as if the hole isn't even there. When Detective Konokawa asks the two bartenders where the hole leads, they look away. Well, they don't have any answer - they just wrote and directed the jolly thing. Of course, it's all metafictional pomo fun but, really, you can't beat it for a literal and figurative plot hole. Happily, the bartenders, ie the original creators, decide, in their own words, to clean up the mess, though they never explain how.

"What is this?" "A big hole." "I can see that!" Much of the appeal of the film for me stems from the central character, the icy Atsuko Chiba and her playful alter ego, Paprika. Ice queen scientist by day; dream goddess by night, she leaves all the male characters in her wake as she unravels the machinations of the dream terrorist. While all around her are losing their minds she is the one who saves the story from its postmodern absurdities. (With the help of the barmen, of course.) The other characters, other than Detective Konokawa, tend towards caracature, all with some level of absurdity. Konokawa, for his part, is earnest and somewhat dull. To an extent he plays our eyes in the story, sharing the astonishment and bewilderment with the viewer. In addition he has his own issues to resolve. (With the help of Paprika, of course.) The film also plays opposites against each other. Paprika herself provides a list at the preposterous climax: light and dark; reality and dreams; man and woman. All you need is to add the missing spice: Paprika. Or so she says. Opposites are also played out in the major character relationships: Slender, anal Atsuko with obese, oral Tokita; physical man of action Konokawa with his best friend - dumpy, ineffectual chief Shima; crippled chairman Inui with his Adonis-like homosexual lover Osanai. I've never quite got the metafictional point of these highlighted opposites. Perhaps they're adornments in the way the christian symbols adorn Neon Genesis Evangelion. I'm open to explanations.

Sexual opposites: the chairman as phallus, standing erect for the first time; and DC Mini as uterus (from the DVD / Bluray menus) My major problem is I've watched Paprika so many times I've quite possibly killed it as entertainment. I've done the same to the Lord of the Rings movie trilogy to give a non-anime example; on the cusp of doing it to Noir; and well on the way with Puella Magi Madoka Magica. I've done it with many a favourite musical piece. Obsession does that, unfortunately. It means I now see some of their shortcomings that I may have glossed over previously. Paprika's piss-take climax doesn't work for me but that isn't a deal breaker. Nor is how gross both Inui and Tokita can be. The former is the villain, after all but Tokita's portrayal does veer towards ridiculing obesity for its own sake. More concering is that all the good guys are straight, while all the villains are gay (Inui, Osanai and Himuro). While it may be part of the opposites dynamic being played out - different is creative, same is oppressive - it smacks of homophobia. I also remain unsure about the rape scene. Osanai insists he loves Chiba/Paprika, while Paprika retorts that his actions are about power, so it seems that is the authorial sentiment. Worthy for sure, but the seriousness of the scene - undermined by the corny rescue - in this instance doesn't sit well with rest of the film. Despite it occuring in a dream don't forget that it is a shared dream. Even if there isn't an actual body that is being violated, it somehow feels like the notion of rape is being used as part of the meta games. I contrast it with the famous, analogous scene from Perfect Blue, where the horror of rape is demonstrated by two actors. The moment in that film where, during a break in filming, the male actor apologises to Mima is a stroke of genius. Paprika, though the better movie overall, can't match it. Both dub and sub are adequate to the task. The sub, naturally, has the advantage of Satoshi Kon and Yasutaka Tsutsui playing the roles of the bartenders. Legendary seiyuu Megumi Hayashibara does Paprika well but is too high-pitched for Dr Chiba; while Cindy Robinson has the right range for Chiba but is too childish and too fake as Paprika. The dub script is wordier - presumably to match the lip flaps - so the verbal gags sometimes aren't as snappy. I prefer George C Cole's Detective Konokawa but, beyond that, I'm not fussed. I tend to watch the dub version, simply because it allows me to immerse myself in the visuals without the distraction of subtitles. Satoshi Kon again teams up composer Susumu Hirasawa from Millennium Actress and Paranoia Agent for the soundtrack. Although several of the tunes aren't all that appealing as stand alone items they work well in the context of the film. Some of the success of the opening credits is due to his Meditational Field, which, along with the closing The Girl in Byakkoya perfectly captures the wonder of the film. And, despite, being made on a small budget, it is still, after nine years, visually dazzling. Rating: masterpiece. As in Tokyo Godfathers, Satoshi Kon places a shout out to his earlier films in Paprika but goes a step further this time. Paprika recommends that Detective Konokawa sees the film Dreaming Children. When Konokawa arrives at the cinema we see above him advertisements for Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress (with the much maligned American character design for Chiyoko) and Tokyo Godfathers. You can also see a slither of what appears to be the Paprika promotional artwork. Above the entrance is the hoarding for Dreaming Children, the original planned title for his next film, later changed to The Dream Machine. Satoshi Kon died before he completed it.

The dream evaporated. Further reading: Justin Sevakis's rapturous review. Mike Toole's article The Dreams of Satoshi Kon: Chapter VI - The Endless Dream Paprika (novel), Yasutaka Tsutsui Satoshi Kon, the Illusionist, Andrew Osmond Over the next week I plan to move here reviews from other MIFF anime I've seen from the What are you watching right now? Why? thread. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 13, 2019 4:08 am; edited 2 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

As threatened, here's the first of my retrieved reviews of anime seen at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF). A Letter to Momo was shown as part of MIFF in 2012 and then shown again as part of Madman Entertainment's Reel Anime Festival in 2013. I've included here both my original review of 08 August 2012 and my additional comment of 12 October 2013. I've edited the first to clear some ambiguity, add some pics and to bring the formatting in line with other posts here.

It's disappointing that Madman haven't released it as a DVD or Bluray. I guess I may have to import it from the US.

Momo arriving by ferry at her new island home, with the unfinished letter. **** A Letter to Momo Context: It was a cold, wet, blustery, winter’s morning here in Melbourne when I caught a train to the city to see A Letter to Momo at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Federation Square as part of the Melbourne International Film Festival. It’s a fantastic venue with a huge screen and with seating for about 400 people. It’s steeply tiered so that wherever you sit there is an uninterrupted view of the screen. I arrived about twenty minutes before the start and got myself a great spot about five or six rows back in the centre. Shortly afterwards a young bloke sat down two seats to my left and settled himself in nicely with biscuits and a thermos full of coffee (did that smell good, or what!). On my right three people made themselves comfortable and began to tuck into some very Asian smelling food. One of the things they had didn’t smell the best but the rest was mouth watering. And I thought I was there for the visual and aural experience. Just before the film began the first school group arrived. They were all girls and filled the rest of my row and the two in front. They must have unsettled the guy on my left – I didn’t smell coffee thereafter. They were shortly followed by a second school group, this time mixed, who filled the rest of the rows to the front of the cinema. All the students were actually well behaved and added to the atmosphere. Given that A Letter to Momo has a school aged heroine (11 or 12 years old, perhaps), they responded appropriately to the film’s many emotional highlights. They were good. The film deserves credit for engaging them so effectively. On to the film itself. Synopsis: Following the death of her father (who left a letter that never got beyond a salutation), Momo struggles to come to terms with her grief and guilt, and finds herself distanced from her mother. When the two move to a new home on a remote island in the Japanese Inland sea, Momo befriends a young boy and his perceptive younger sister, an absent-minded, timid postie and three highly entertaining goblins. With their help Momo begins to see things differently, gets some notion of what her father had wanted to write to her, and prepares to take the plunge into her new life on the island.

Momo is slow to warm to the goblins. Comments: One of the things that struck me from the beginning of film is how Momo is, or more correctly isn’t, presented to the viewer. There are no obvious visual cues, a la anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day to indicate the personality type. Clearly Momo is depressed: she even comes across as sullen. In appearance she is part Kei from Jin-Roh - The Wolf Brigade (Hiroyuki Okiura directed both), part Chihiro from Spirited Away and lots of Makoto from The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (though somewhat younger than Makoto or Kei). Indeed, visually it follows the style of Mamoru Hosoda’s two recent movies. That may be just current fashion or perhaps due to the involvement of production house Kadokawa Shoten in all three. Getting back to Momo, she is no kawaii, moe, or dere dere standard type. She is someone we are going to get to know over the course of the story. And the film is happy to take its time in the telling. She may be a regular schoolgirl, but she’s a very real seeming, regular schoolgirl. One of the marvels of the film is the way it captures a girl on the cusp of puberty. Her body is still a child’s, but she views people and events and objects not always in the self-centred, acquisitive, curious way of a child but frequently in an appraising, measured way of an adult. Nevertheless, she still has a child’s lack of self-consciousness about her body: she constantly moves and deploys her limbs in a very naturalistic, innocent way. Indeed, another of the great things about the movie is the natural way everyone moves. I think it’s one of the best anime I’ve yet seen in this regard. All the same, like so much anime, the camera loves to linger on her body, though it is done in a chaste, rather than fanservicy, way. As an example, the moment that got perhaps the biggest laugh from all the school kids in the audience, along with the rest of us, is when Momo, lying on her back on the floor and suffering severely from malaise, wants to move but cannot raise the energy to stand up. She slides across the room on her back by pushing with her feet. It's a moment everybody could relate to: you’re down in the dumps so you end up doing something silly and pointless because you just couldn’t be bothered. If there’s a problem with Momo it’s that she’s just a bit too ordinary. But, then again, it makes it easy to relate to her and, therefore, sympathise with her. Other than the goblins, none of the other characters get a real lot of screen time. Even Ikuku - Momo's breezily cheerful but struggling mother - is mostly offshore, attending a care givers course (the irony there is stark). Initially, I found the goblins problematic. Until their appearance, the story suggests a strong sense of realism, other than the three water droplets that are our first hint of what’s to come. The effect of the goblins is to upset the apple cart (or, more correctly, the mandarin cart) of seriousness that had prevailed until their entrance. The film gets away with it because they are so appealing, despite a tendency to grossness. I won’t elaborate further other than to say there are a couple of really gross yet hilarious moments involving bodily actions that should be enjoyed without forewarning. In a movie like this you know form early on that it’s going to have an emotional resolution. It doesn’t skip on that promise. Two big tear drops fell from the centre of each eyelid onto my cheeks – I must have been holding my head perfectly straight at that moment – as Momo and we finally get the answer we’d been waiting for from the beginning. Given the anime community’s current penchant for a strong emotional involvement with characters and story then I’m sure this film is going to be a winner. This film is Hiroyuki Okiura’s first directorial effort since Jin-Roh - The Wolf Brigade in 1998. They have very little in common other than they are both very typical products of their time and have a slight similarity in character designs. Neither are or were particularly groundbreaking in their visual style or subject matter for their time but both films excel in important areas – artwork, animation and story telling. The quality in both just shines through. Perhaps in Momo the human characters are a tad ordinary and the goblins just a little too silly but I sure hope I get to see more films from Okiura in the future. Rating: I find that I come away from cinematic anime experiences with an enthusiasm that wanes over time. I'll be harsh and rate Momo as very good. It approaches The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and Summer Wars in its appeal and is somewhat better than any of Miyazaki's post - Spirited Away efforts. The MIFF has been supportive of anime. Since 2007 I've seen Paprika, The Sky Crawlers, Summer Wars, First Squad - The Moment of Truth and now A Letter to Momo. In that time it has also shown at least two more - Tekkonkinkreet and Mai Mai Miracle. ****

Taking the plunge. **** A Letter to Momo I saw this at Cinema Nova in Carlton this afternoon as the final instalment of Madman's 2013 Reel Anime Festival. I won't say much about it here because I saw it a year ago at the Melbourne International Film Festival where it was shown in a much larger, packed, venue on a huge screen. At the time I said I'd be harsh and rate it very good. On a second viewing, I've no doubt I was indeed too harsh so I've upped the rating to excellent. It never drags for a longish movie - 2 hours - while Momo and the goblins have grown on me even more since my first viewing. If this were a Ghibli movie, and it's better than anything from them since Spirited Away, it would have been rated by 1450 ANN viewers by now, not 145. This is a gem that seems to have flown below people's radar. It deserves to been seen by a wide audience.

Momo and goblins. The guy on the right is about to display an explosive talent when dealing with wild boars. While seeing it in a smaller theatre added to the intimacy, the smaller images reduced the physicality of the goblins as well as Momo's body and movements. And, even though I knew what was coming, I had a reprise of tear drops plopping onto my cheeks at the big reveal, though not with the previous perfect symmetry. **** Theron Martin's review can be read here. And, no, I didn't plagiarise the synopsis from the ANN encyclopaedia. I wrote both. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 13, 2019 6:01 am; edited 1 time in total |

||||

|

||||

|

dtm42

Posts: 14084 Location: currently stalking my waifu |

|

|||

|

^

Why does no-one ever talk about the fundamental plot hole in the movie? You know, the one that completely destroys the whole climax? Yeah, that one. Thematically it doesn't have any impact, but it sure matters if - like me - you care about the plot. |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

Please elaborate. |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Stepping ahead to the 2014 MIFF where, unlike this year, we had an embarrassment of anime riches. Here's the first of three memorable films. This review was originally posted on 10 August 2014. I've replaced the MIFF promotional pics with screenshots from the Madman DVD release. I haven't changed my mind on its masterpiece rating, making it my highest ranked Ghibli film.

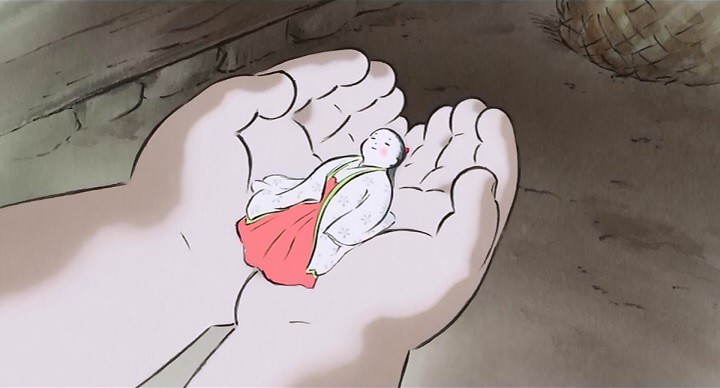

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya Saw this yesterday as one of three anime films being presented by the Melbourne International Film Festival. The Story: An old bamboo cutter discovers a tiny girl nestled within a glowing bamboo stalk. Overjoyed, he takes her home where, with the help of his wife, he raises her amidst rustic simplicity. The girl rapidly grows into a beautiful young woman. Later he discovers a fortune in gold nuggets along with the finest garments and interprets this to mean that she is of royal blood, to be treated accordingly. With his new found fortune the bamboo cutter sets up her up in a villa in the capital, buys himself a title and employs tutors to transform the country girl into a refined woman. News of her beauty spreads rapidly. Powerful and wealthy suitors compete for her hand in marriage culminating in a proposal from the emperor. All the while Kaguya wishes that she and her family could return to their former life and to be reunited with her sweetheart, Sutemaru. Sooner or later, though, her true origins will make their own claim upon her.

Princess Kaguya is no Thumbelina. She rapidly (and humorously) grows into a normal sized young girl. The Venue: Seven years to day that I saw Paprika and had my passion for anime kindled I rocked up to the same cinema (The Capitol in the city) and the same film festival (though seven years apart, of course) and rediscovered all over again why I love the art form. Not since Paprika have I experience so much joy and wonder in anime. The Capitol Theatre is the most amazing cinema space I have ever been in. Designed by American architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, it has a ceiling so wondrous that, if ever a film should pall, one need only look up to have one's enthusiasm renewed. Whenever I've been there I've felt a buzz among the patrons: the place does that on its own. It was a big crowd too: a full house of 600, with all seats pre-sold and people queuing down the street in the centre of Melbourne to get the best spots. At AU$19.00 a pop that's over a million yen added to the film's bottom line. The woman to my left had a North American accent while the bloke to my right complained that the seats had shrunk since he was last there (meaning he had put on weight). We're lucky to still have the venue. In the 60s it was earmarked for demolition. RMIT University, who currently own the building, are in the process of restoring it.

The combination of watercolour, pastel, CGI and animation is a marvel. The Film: The thing thats stands out immediately is that, while it is quintessentially Japanese, this film looks like few anime you may have ever seen. At the risk of sounding critical, it reminded me of Folk Tales From Japan but with a much bigger budget, even more heart and sophistication, and an eye for beauty glimpsed only occasionally in the TV series. The artwork is all pastel, watercolour and white space, which may have been an illusion as the parallax effects from time to time betrayed the use of CGI. Whatever the production methods used, the combination of tenth century magical tale and the traditional art style evoke a peculiarly Japanese mythology and sensibility that is paradoxically both artificial and timeless. While there are characteristic Isao Takahata stretches of stillness, there are frequent moments of thrilling movement: such as the appearance of a shimmering lake in a travelling camera shot; or when two lovers falling from the sky make the most startling change of direction; or when Kaguya runs back to her village in a sequence that is all black and white but for her red hakama. It's a flashiness quite unexpected from Takahata but adds to the enchantment he casts over us. Even simple body movements are animated with flair. Given the simple seeming artwork it is quite an achievement.

Simple. Stark. Beautiful. That magic in the animation is there in other ways right from the start: in the discovery of the miniature princess in the bamboo; her freaky spurts of growth; the old woman suddenly producing milk; the games of the children; the change of seasons; in how Kaguya seems to bring everything and everyone to life, like a caress of spring air. Moving the setting from the bamboo grove to the city may necessarily cause the film to forsake its rustic innocence but it doesn't lose its elan. The bamboo cutter tries hard to be dignified but appears a pompous fool, as exemplified by how he loses his hat whenever he walks through a doorway. Kaguya's tutor is more than pompous - she is downright supercilious - and a marvellous creation to boot, probably because we sympathise (or maybe it's just amused) with her astonishment at Kaguya's life force. Kaguya herself is a wonder. She astonishes everyone she meets. Happily, the film is so convincing that the viewer need never doubt that the astonishment is genuine and appropriate. Her mettle is tested with her first five suitors. How she handles them is clever and seemingly imbued with a modern appreciation of her rights as a person. This is a young woman learning the power of her wits and how to make independent decisions and yet, the film is essentially faithful to the 10th century story it is based upon. That supposed modern sensibility is, in truth, much older than we imagine.

Even at its most wistful, Kaguya never loses its sense of joy. If the film has flaws they appear towards the end. Kaguya's behaviour becomes erratic as she begins to understand her true origin. How she comes to know these things isn't explained and so her actions seem unconvincing. In fairness, the original tale also has her coming to realise spontaneously what she is. I didn't know the story until watching the movie and looking it up online afterwards. I suppose, like any legendary tale, someone from within the culture would know the story already and not be bothered by these questions. I don't wonder why Ned Kelly strides out from the Glenrowan Hotel in his suit of armour; I just expect any telling of the tale to do it with the appropriate dramatic effect. Similarly, as an outsider, the Buddha's entrance near the end of the film comes across as cheesy. Unfortunately, things aren't helped by the imagery being reminiscent of Buddha's appearance in the grand parade in Paprika, which, in the context of that film, is highly unflattering. I suppose it would seem natural to a Japanese viewer but, perhaps the Japanese are now so divorced from their religious traditions they are incapable of portraying them convincingly. Nevertheless, the final scenes show all the people whose lives had been touched by Kaguya - those who had nourished and cherished her and even those she rejected - briefly acknowledging the profound effect she had upon them. The verdict: Masterpiece. Better by far than Grave of the Fireflies or Only Yesterday. It is glorious. What a way to end a career! The Wind Rises pales by comparison. It's the only film I've seen where a character falling, breaking his neck and dying elicited spontaneous laughter from the audience. And the guy wasn't evil either, just ridiculous. You gotta see it to understand it. It's an example of how Takahata is such a master at manipulating emotions. Upcoming: On Wednesday I'll be going to the first of three screenings of Patema Inverted at ACMI 2 in Federation Square where director Yasuhiro Yoshiura will be taking part in a question and answer session aftewards, while this coming Sunday I'll be seeing Giovanni's Island, also at ACMI 2. (ACMI = The Australian Centre for the Moving Image.) Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 13, 2019 7:06 am; edited 3 times in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Continuing with retrieving reviews from the 2014 MIFF. This review and Q&A with the director Yasuhiro Yoshiura was originally posted on 13 August 2014. When I got the Hanabee DVD I was able to answer for myself one of the questions the director couldn't - I've added that post from 15 December 2014 at the bottom and some screenshots from the DVD. I've also, since, reduced the rating to good.

Patema Inverted Saw this today as the second of three anime films being presented by the Melbourne International Film Festival. The Story: Patema, a princess of a constricted but mostly happy underground community that knows of no world other than rock and endless tunnels, loves nothing more than exploring the forbidden sectors. After an encounter with a man who walks suspended from the ceiling she finds herself on the surface world where she is inverted - gravity works in the opposite direction for her compared with everybody and everything else. Letting go of an anchor point means falling into the sky. She meets a young boy, Age, who unsuccessfully strives to protect her from the oppressive, watchful guardians of his world. Age and Patema's underground friends must learn to see the world in new ways to save her from captivity while Patema must overcome some of the most primitive fears known to humans: fear of heights, fear of falling, agoraphobia and vertigo. Together they will come to understand the true nature of the world and its peculiar physical laws and perhaps find a way to reconcile their clashing points of view. The Venue: In contrast to the Chicago School splendour of The Capitol, Patema Inverted played at the more prosaically functional Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) in Federation Square just a couple of blocks down the road in Melbourne. According to Wikipedia ACMI is a state-of-the-art facility purpose-built for the preservation, exhibition and promotion of Victorian, Australian and International screen content. This particular screening was part of the Next Gen program of MIFF, sponsored by the Australian Teachers of Media - who have kindly produced a ten page study guide - and supported by the state and federal governments. Nice to know our taxes are being used to expose school children to anime. I like it. I was surrounded by a couple of hundred students but the film kept their attention throughout.

Federation Square, Melbourne, from the entrance of ACMI. Boring fact: there are 13 railway lines beneath our feet. The Film: There is something Satoshi Kon-like in the films of Yasuhiro Yoshiura. Both directors have (or had in the case of Satoshi Kon) a penchant for setting up expectations and then up-ending them. Where Kon used these twists to destabilise reality in an unsettling postmodern way, Yoshiura uses them to overturn old paradigms and replace them with new ones. Patema Inverted continues with his fascination with paradigm shifts but mostly lacks the edginess of Satoshi Kon, the philosophical depth of Time of Eve or the arcanery of Pale Cocoon or Aquatic Language. Its simplicity makes it more accessible than the latter two films but leaves it a notch or two below Time of Eve or the best of Satoshi Kon. The weird premise - gravity being inverted for the heroine - is complemented perfectly by the visuals. The background artwork is gorgeous to look at in the manner of much contemporary anime although it doesn't revel in its beauty the way that The Tale of Princess Kaguya does so profligately. But it is the visual aspect that is the hook for the film. And a huge hook it is. Yoshiura plays to the max the notion of characters having figurative and literal opposing points of view. As well, the constant fear of falling into the sky is visceral and terrifying. The imagery of someone holding on for dear life with just clouds and emptiness below them won’t be easily forgotten. Yet the terror is replaced by sublime joy when Patema and Age discover that by holding onto each other they can fly across the landscape. (People holding on to other people for survival is a major image and theme of the film.) Or when Patema sees stars for the first time, spread out below her. It turns out, too, that the stars themselves have two realities.

I feel your fear, Patema. Patema is game but highly vulnerable. One slip, one false move means a fall into oblivion. The scenes are framed so the viewer is staring into the abyss along with her. We share her terror. The urge is to hold her, to save her from annihilation. For me, it induced some of the strongest moeru reactions I've experienced with anime. At one point, having no other alternative, Patema grasps onto the body of the big bad, the overplayed psychotic Izamura, for anchorage. In that moment he finds a strange pleasure in the sense of protectiveness he feels, but the parent is quickly replaced by his Marquis de Sade nature. The rapid transformation with its sexual undertones briefly has the film prying into an uncharacteristicly dark place for Yoshiura. That moment aside no-one else is as memorable as the heroine. Compared with Time of Eve the characters are flat. Age is stoically loyal; his rival from underground, Porta, is goofily good-hearted, the authority figures from the upper world are stiff and overbearing. Actually, stiff is a good description for many of the characters. The designs are unexceptional, bordering on dull, and they even hold stiff poses much of the time, although their movements are fluid, which makes for an odd mixture. The orchestral soundtrack from veteran Michiru Oshima (The Weathering Continent, Fullmetal Alchemist, Little Witch Academia among others) ranges from suitably lyrical to overbearing - even when it's not supposed to be. The theme song is sweet, though. The Verdict: Very Good. This is a film that ought to be seen on a big screen. A small screen will limit its highlights and highlight its limitations. The Interrogation: The writer and director, Yasuhiro Yoshiura, is a guest of the festival. He was introduced before the film and answered questions afterwards through an interpreter. I took notes with a pen and paper until my pen died about half way through - that's what I get from relying on old technology. I think I've remembered all the questions and answers. This isn't a verbatim account of the session but the gist of what was said. Apologies if I've misrepresented anyone - it isn't intentional. Yoshiura is a short, compact man, unassuming it seems, considered in his replies and a couple of times struggled to answer. He was well received by the audience. (Oh, and I didn't ask any of the questions.)

It's a terrible photo. I'm sorry. Question. How important is allegory to you? Yasuhiro Yoshiura. I'm interested in oppressed societies, not for political reasons per se but as entertainment. I got a lot of my inspiration from Hollywood. Q. I can see Romeo & Juliet, Nineteen Eighty-Four and Philip K Dick. Can you tell us the sources of your inspiration? YY. I love movies. I'm influenced by favourite movies. The story is a conventional boy meets girl. My favourite movies include Nineteen Eighty-Four, Brazil and Gattica. Q. Your heroes are challenging dogma – why did you chose teenagers? YY. The age of Patema and Age is 14 – halfway between a child and an adult. Aiga (the surface city) is the source of evil (sic). Q: Are you from Aiga or the Sakasama world? YY: To be honest – from Aiga. I am Age or the big baddie Izamura.

No. No. You're not the big baddie, Yoshiura-san. Q. Your first and second names are anagrams. Did that inspire your inverted world? YY. Aaaaaah. It can be inverted. Since a child I have always looked into the sky and thought I would fall into it. So I decided to make a film. Q. How long was the filmmaking? How difficult? YY. Pre-production was one year, making the film, two. The most difficult thing was to make sure it started right. The animator was confused which way was up. Q. Did you make the film with western audiences in mind? YY. I wanted western audiences to watch the film so I made it simple. (The audience laughed as Yoshiura seemed to realise he may have committed a faux pas.) Q. I can see similarities with Pale Cocoon. Was that deliberate? YY. It was the same person making the film so the same things will be said. Q. Were there any issues writing the screenplay? YY. After I came up with the inverted worlds I struggled to work out how to finish the film. Then I thought of a false ceiling and everything fell into place. Q. There are some great ideas in the film. Do you plan to expand on them? YY. I have a great idea for a new project but telling you now would spoil it. Q. At the end of the film why doesn’t the notebook from the other society float away in the inverted gravity? (This created some alarm between YY and his interpreter.) YY. Someone was holding it. (No argument from the audience.) YY. Phew! Q. I noticed some encrypted mail towards the end of the movie. Is there a secret message for the audience to decipher? YY. It isn't a mystery but it is important. You will need to buy the Bluray to read it. Q. When developing the characters did you base them on people you know? YY. Yes. When I was working out how the characters should behave I asked myself what my friends would do. I am in the characters also. Autographed film posters were given to the two best questions. Yoshiura awarded one to the person who asked the hardest question - why the notebook didn't float away, while the moderator awarded the other to the Pale Cocoon questioner for being a long term fan. Upcoming: Giovanni's Island on Sunday. Not so boring fact: According to the very nice promotional brochure handed out, Time of Eve was iTunes's third most downloaded movie of 2011, after Toy Story 3 and Inception. **** Back in August I saw Patema Inverted at the Melbourne International Film Festival. Director Yasuhiro Yoshiura was a guest of the festival and answered questions after the session. You can read the questions and answers here. The most intriguing moment was this one:

My pre-ordered copy of the DVD finally arrived today (only twelve days late) and, strewth, Yasuhiro Yoshiura has got it totally wrong.

The person with the notebook resting on his palm is Elder - one of the underground people. Nearest to him is another undergrounder - Porta - and further back is Jack, from Aiga, who, as can be seen, is affected by gravity differently from the other two. The notebook is also from Aiga - it belonged to Age's father - and we initially see it resting appropriately on the floor of the Aigan flying device. As the above questioner observed, without being held down it should have fallen into the sky. Oh dear! (Perhaps Elder has his left hand resting on the book? Yeah. That must be it.) ~ An extra on the Hanabee DVD shows Yasuhiro Yoshiura visiting Healesville Sanctuary on the outskirts of Melbourne where he is filmed goofing around with Hanabee staff in front of koalas and emus. Is this extra included on the US or British releases?

~ The printed email at the end of the film mentions the following co-ordinates: Latitude 33.3526' N, Longitude 130.2401' E. That is the location of Fukuoka, where Yasuhiro Yoshiura grew up. **** I've dropped my rating of Patema Inverted a notch because, beyond the startling premise, which is executed pretty well it must be said, most of the other elements aren't all that memorable. The characters are unoriginal - the big bad is especially annoying - and the social commentary is of the standard "oppression is bad" variety. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 13, 2019 7:29 am; edited 1 time in total |

||||

|

||||

|

Night fox

Posts: 561 Location: Sweden |

|

|||

Wouldn't people from the (inverted world?) be able to balance out the inverted gravity, by wearing e.g. belts and shoes with built-in lead weights from the "normal" world? |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

^

I got vertigo trying to read your post. To answer your question, you'd think so. If I recall, the big bad used weights to tether Patema. For the most part, though, Yoshiura uses ceilings, rather than weights, to constrain the characters. Not only does a ceiling turn out to be a major plot point (as he points out in his Q&A) but it fits in with the theme in his earlier films of breaking out of constricted space. |

||||

|

||||

|

dtm42

Posts: 14084 Location: currently stalking my waifu |

|

|||

The climax of the movie is Momo's mother having a serious asthma attack during a typhoon. In order to save her, Momo needs to summon a doctor who is on a neighbouring island, but in order to do that she needs to survive the storm whilst crossing the bridge. The yokai big and small work together to form a tubular shield for Momo to ride through, and she successfully makes it across the bridge. Errinundra, you seem like a wise and intelligent fellow. So tell me; how did Momo and the doctor get back across the bridge to save her mother? So yeah . . . the movie's climax is built upon that plot hole. |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

Don't be fooled by appearances.

My schedule is full: I'll have to leave that gaping until the weekend so I can re-watch the ending. |

||||

|

||||

|

dtm42

Posts: 14084 Location: currently stalking my waifu |

|

|||

|

^

No problem. I left you hanging for a few days (totally by accident I swear, I completely forgot to check the thread), so I don't mind you taking a few days to get your answer in order. |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

^

It's absolutely clear in the film how she gets back: the same way she got across the bridge in the first place. As they arive on the other side of the bridge Momo yells out, "Please wait for us!" to which the farting goblin replies, "I hate rain. Please make it quick!" |

||||

|

||||

|

Errinundra

Moderator

Posts: 6584 Location: Melbourne, Oz |

|

|||

|

Life & family intervenes. This was supposed to be posted yesterday. It's the last of the MIFF reviews, originally posted 17 August 2014. I've replaced the original promo pics with screenshots from the Madman DVD release.

Giovanni's Island Saw this today as the last of three anime films being presented by the Melbourne International Film Festival. The Story: An old Japanese man revisits Shikotan, an Island in the Kurils, where he lived as a child until its occupation and annexation by the Soviet Union. The journey revives memories of those events, especially his family’s struggles to adapt to the new circumstances, the bravery of his father and his schoolteacher, the scheming of his uncle, the Russian girl he meets and falls for, his evacuation from the island to Sakhalin, and a desperate journey with his ill brother to be reunited with their father. The Venue: It was back to ACMI 2 in Federation Square. Disappointingly, the audience was small, although it had screened already a week or so earlier. The Film: Giovanni's Island uses two framing devices to orient the movie in time, space and also thematically. The first is the seizure of the South Kuril Islands (including Shikotan) by the Soviet Union at the end of World War 2. While Russia had historical claims to other parts of the archipelago, they had never previously administered the South Kurils. The Japanese population was evicted in 1947 and repatriated to mainland Japan. Russian administration of the islands continues to be disputed by Japan. In the film two former residents - Junpei, who was a student at the time, and his teacher, Sawako - return for the first time at the invitation of the Russians to take part in a school reunion as a goodwill gesture. The film is seen through Junpei's eyes and he provides the occasional narration. The second framing device is the classic Kenji Miyazawa children's novel, Night on the Galactic Railroad. I would imagine that most Japanese viewers would be familiar with it. In that story Giovanni must work hard to care for his sick mother in the absence of his father who is missing so has no time to socialise with his peers at school. His only friend is Campanella. One day Giovanni has a dream of journeying with a soaking wet Campanella by interstellar steamtrain to the Southern Cross constellation. When he awakes he discovers that Campanella has drowned. The train thus becomes a metaphor for both permanent separation and for the journey into the afterlife. In the film we learn that Junpei (Giovanni) and his brother Kanta (Campanella) were named after the novel's main characters. Ominous or what?

Tanya takes the boys' Night on the Galactic Railroad into what used to be their home. She doesn't mean badly. The film can be divided into two halves: life on Shikotan before and after the arrival of the Soviets; and what happens after the eviction - set mainly on Sakhalin, where Miyazawa wrote much of Night on the Galactic Railroad. Despite the obvious conclusion one may make, the framing devices apply throughout the movie. For me, it was the first half that resonated the most. I was captivated by the life of the islanders, their reaction to the end of the war and the arrival of the Soviet troops. Despite their fearsome demeanour and reputation ("they kill bears with their hands") the Soviets are portrayed, if not entirely sympathetically, then without condemnation. For sure, Junpei's family is evicted from their house and into their stable so the commandant can take their place but he (the commandant) treats them kindly nonetheless. Junpei's father is arrested and sent to a prison camp but there is no hint of maltreatment in the film (though there probably would have been in real life.)

Figuring Tanya can't recognise Japanese names the boys introduce themselves as Campanella and Giovanni We see all this through the innocent, ignorant eyes of the young Junpei. Which is weird, because the framing device is the older Junpei reminiscing. You would think some editorial commentary from the older man would intrude. In any case, the developing relationship between the Japanese and the Russians is, for the most part, entertaining (tempered by some disturbing developments), especially the way the school kids from the two groups come to an accomodation with each other. They start off trying to sing nationalistic songs over each other and end up singing the others' songs. From warily eyeing each other in the school yard, they break the ice by playing tag together. When Junpei accidentally knocks over the commandant's daughter, the pretty Tanya, she defuses a likely brawl by ostentatiously blowing a kiss into his ear. Their subsequent friendship becomes a metaphor for what might have been: they are forcibly separated by the 1947 expulsion of the Japanese from the islands with nothing more than what they can wear or carry personally. From that point the film takes a darker, more emotionally fraught turn as Junpei, Kanta, their teacher and their uncle travel by ship to Sakhalin where they face an uncertain future. When they learn that the prison camp holding Junpei's father can be reached by train, the parallels with Miyazawa's tale become stronger and the outcome, for all its seeming inevitability, is still emotional, though not nearly as much as I expected. Whenever a sad story is required to carry a philisophical argument - yes, the South Kurils have been lost, but it's time to be strong and work hard for a happy future - I find that I'm detached from the emotion. That's not to say that the message isn't a worthy one, it's just that the message and the story are working against each other to an extent.

I don't know about you but I see an allusion to Grave of the Fireflies. The artwork and animation are a curious mixture of styles. The simple character designs can be rough, while furniture and other nearby objects have detailed textures with 3D shapes, even if they may be misshapen at times. The landscapes can be exquisitely detailed and natural looking while the clouds and other objects might be highly abstract. The blending of naturalism, artificiality and abstract expressionism matches the blending of the hard reality of the characters' lives with the fantasy of Night on the Galactic Railroad. It's not always convincing. All the same, I always appreciate anime that breaks away from the straightjacket norms so typical of the industry. Overall, it's visually appealing, though nowhere near being in the same league as The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. The verdict: Very good. The film tries to parallel the loss of the South Kuril Islands, the classic tale of Night on the Galactic Railroad with the story of Junpei's attempt to be reunited with his father after their eviction from the islands. Junpei's story is affecting and memorable, however the parallels tend to come across as extraneous. **** Todd Ciolek's ANN review can be read here. Last edited by Errinundra on Fri Sep 13, 2019 7:44 am; edited 1 time in total |

||||

|

||||

|

dtm42

Posts: 14084 Location: currently stalking my waifu |

|

|||

Indeed. My point was - dai shockuu - not that they couldn't physically get back, rather that the doctor would have to undergo the same weirdness which caused the postman to faint. I wonder what the doctor thought of the magical tunnel through the storm and the yokai swirling around him? Oh wait, they never touch on that. How odd . . . It's obviously not a plot hole that bothers most people - if they even realised there's a plot hole in the first place - but it bugged the heck out of me. I had difficulty concentrating on the finale and the emotional resolutions. I hate artificially convenient writing like that, especially when it is so glaring. Still a good movie though. For all of my griping about that one plot hole, I still rated it the same as you did. |

||||

|

||||

|

All times are GMT - 5 Hours |

||

|

|

Powered by phpBB © 2001, 2005 phpBB Group