Review

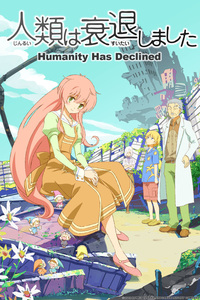

by Carl Kimlinger,Humanity Has Declined

Episodes 1-6 Streaming

| Synopsis: |  |

||

The distant future. Humanity has declined. The remnants of the once-mighty species have been reduced to living modest rural lives, scraping together enough food and electricity to get by while the world they built crumbles into oblivion around them. There are still governments and organizations, though much reduced in power and reach. An unnamed girl in one small village—we'll call her Watashi as she calls herself—works for one of them. The UN specifically. She's a mediator. Which mostly means that she's a liaison between the village people and the fairies. Yes, fairies. They're tiny and adorable and love sweets and games, but they're also capricious and gifted with god-like technology, capable of building literally anything that can possibly be imagined. So despite her blasé attitude Watashi's job is very important, as the mischief the fairies get up to, helpful intentions notwithstanding, can be quite dangerous. |

|||

| Review: | |||

AIC's nearly unclassifiable post-apocalyptic comedy/fairy-tale is a brilliant but ultimately uneven animal, a work of towering imagination whose wacky unpredictability sometimes leads it into dead-end stories. When it works it's a comedy unlike any on the market; when it doesn't it's a self-indulgent bore. The brilliant outweighs the uneven, but at times it's a real battle. The first of the series' largely independent short stories introduces us to the show's gentle take on the end times, in which humanity finishes its run not with the flash of nuclear war or the dead rising from their graves but with a slow fading into ruin. While the ruins that tower around them attest to the heights humanity once achieved, Watashi's people live lives of quiet deprivation, subsisting as villagers in medieval Europe might have: on what they grow in their gardens and find in the woods. It's an essentially melancholy vision, made strangely appealing by the friendly fatalism of the villagers and the bright atmosphere that the show wraps their hopeless situation in. It may be the end of mankind, but it's a beautifully colored end populated by likeable archetypes (no one has names, only titles) and fanciful beasts given life by unknowable technologies. It's but one of the series' many inspired inventions: the apocalypse as fairy tale. The series' post-apocalyptic vision has a certain built-in humor, both in the fairies—who multiply unless kept blister-packed at night—and in Watashi herself, whose caustic inner wit and unflappability in the face of absurdity are frequently hilarious. But it's only when the first story heads to a suspicious factory (it's been pumping strangely inhuman products into the local economy) that the sheer insanity of the series' comic imagination becomes clear. Specifically during a tour guided by a sentient loaf of bread, who at the tour's end offers himself up as a taste-test by ripping himself in half and spraying the horrified Watashi with his blood-red carrot filling. The episode that follows features cigar-smoking chicken carcasses bent on world domination, a Looney Tunes chase during which chickens hide in factory machines that turn them into chicken products, and several church-unapproved uses of the Ave Maria. It's a feast of comic invention unseen since the very best episodes of Mitsudomoe and Is This a Zombie?—and in a series that is clearly twice as smart as either. The series doesn't just take Arthur C. Clarke's famous sci-fi law (“any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”) at face value, but later puts out its own spin on it (call it “life in a sufficiently advanced civilization is indistinguishable from bad fiction”) that is both very funny and, upon reflection, eerily logical. At this point the series is nearly perfect: balanced between hilarity and melancholy; intellectually engaging and yet hugely entertaining; and blessed with a thoroughly delightful female lead. There's no way, it seems, that it could maintain that. And it doesn't. The next story introduces the fairies to the wild and wooly world of yaoi doujinshi, prompting them to concoct their own manga, in which the readers become the characters and must pander to their audience or be cancelled. Watashi and her companions try out cliffhangers, shocking plot twists, and creative reinvention, all with dire consequences. Perhaps if you're a manga artist or doujinshi aficionado, or at least a manga enthusiast, these episodes will be funny, but to the rest of us they're one long in-joke, the punch-line to which we're not necessarily privy. The advantage of the series' premise—in which technology can do anything but is controlled by essentially a civilization of ADD children—is that it allows the series to do pretty much whatever it wants. That it wanted to do something as tedious as a two-episode self-appreciation of manga/anime culture is worrisome. Series director Seiji Kishi is, appropriately enough, an artist who splits his time pretty evenly between the surprisingly good and the brain-bleedingly bad. He is more reliably skilled at comedy than anything else, so it isn't a shock that he does humor quite brilliantly, lavishing hilarious care on a John Woo shootout with naked chickens and timing Watashi's mile-a-minute internal and external dialogue with screwball aplomb. It is a surprise, though, how well he does everything else. The storybook simplicity of his backgrounds fits the fable-like tone of the series to a tee, as do the equally simple score and colorful character designs. His action scenes—the ones that aren't jokes—are fairly perfunctory and as ever he relies more on editing and headlong pacing than actual animation to keep the energy level up, but those aren't such lethal issues with a little stylistic focus to back them up. He's produced a series that looks and acts pretty much exactly like what it is: speculative post-apocalyptic fiction written by manic comedians and delivered as a fairy tale. If the series' second story is reason for worry, its third is an answer to those worries. The right answer. It's a madcap journey through the remains of an ancient city that mixes the mad comic impulses of the first with a touch of the second's concern for anime convention while adding its own little emotional edge for a marvelous return to entertaining form. Like the factory tour before it, it's a tad insane, a tad more clever, and littered with funny, surprisingly interesting sci-fi ideas. (The pushy helpfulness of the dead city's gelatinous technology is dead-on considering current technological trends, as is Watashi's primitive terror when confronted with it.) But more importantly it also brings back the hint of melancholy that haunted that first story's edges. It's there in the Human Monument Project's opening festival, which seeks to celebrate humanity's past but can't help being a sad reminder of how far the species has fallen. And it's there in Oyage and Pion, the deeply odd robots who provide the impetus for the tale and whose back-stories are steeped in cosmic loneliness. It isn't enough to spoil the fun mind you, but it is enough to let you know that the series' bittersweet heart still beats. Though it is telling that the story's most poignant moments are given over to a pair of anime parodies whose down time is spent being 2001: A Space Odyssey parodies. |

|

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of Anime News Network, its employees, owners, or sponsors.

|

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall (sub) : B

Story : B+

Animation : B-

Art : B+

Music : B

+ A highly imaginative and frequently hilarious show about the slow death of humanity; excellent heroine; surprisingly solid sci-fi ideas. |

|||

|

discuss this in the forum (16 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history |

|||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about |

||