Game Review

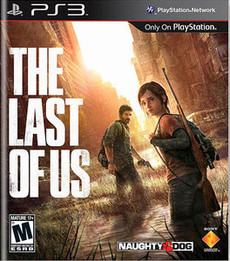

by Dave Riley,The Last of Us

Playstation 3

| Description: |  |

||

It's been twenty years since a fungal infection brought down humanity. Joel and Ellie are two travelers on a cross-country mission of hope. |

|||

| Review: | |||

Cannibals, roving bandits, man's inhumanity to man, people living on borrowed time, totalitarian government: there's no shortage of zombie cliches. There are enough of them to fill scores of books, movies, and video games over the years -- with most of the recent ones shouting some variation on the incredibly banal realization "WE are the Walking Dead!" The Last of Us certainly hits most of the major tropes. Twenty years after the world has exploded humanity shuffles along, cowering in quarantine zones, hiding from fungus-headed zombies who spread their plague by spores as well as bites, for if there were no bites then there would be nothing for infected characters to shamefully hide before they turned. The opening of the game is about as frank and unkind as any opening to any game has ever been. It is affecting, though it is only slightly more playable than a cutscene. It is what the Dawn of the Dead remake's opening scene ought to have been, but could really never hope to be. Its emotional beats are simple, but effective. Twenty minutes isn't enough time to create fully fleshed out characters, but it's enough to seed them with a few traits, it's enough to build up their skeletons, such that they can be used to hurt you. The prologue is a warning: The Last of Us is cruel.

Two people start a cross-country trek for the usual post-apocalyptic reasons. There's Joel, a middle-aged man bordering on an old man, and Ellie, a child bordering on an adolescent. She don't like him and he don't like her, though we know that's not bound to last. They will bond as characters in these stories do: over survival, over food, over the murder of bandits and zombies. The Last of Us has hundreds of bandits and zombies. It has about three times more enemies than are necessary in every combat encounter, which makes sense given this game's Uncharted lineage. The bad guys here take comparatively fewer bullets, which is great considering ammo is so tight… or it seems tight, anyway. You will pretty much have enough ammo to shoot through every encounter, even though it seems like you are constantly running low, and you will have enough scissor bits and fertilizer sacks to craft enough shivs and improvised bombs to get you through. Honestly the worst crime The Last of Us perpetrates in the name of scarcity is not always doling out enough bullets for your favorite gun. There's a lot more movement than you'd expect from a cover-based shooter. Enemies actually bother flanking, so firing more than one or two shots from a single position can be dangerous. Joel is fragile, by video game standards, and there is no gradually filling red skull in the center of the screen, warning that you might want to retreat to cover, sometime, maybe, if you feel like it, no big deal (though there remains the industry-standard strawberry jam smeared on the camera lens). Instead, if Joel is out of cover too long he will be shot, and that will put him on his ass. Unlike in Resident Evil 6, where being laid out by a thousand enemies shooting a thousand rounds a minute felt cheap and infuriating, here the frustration serves a purpose: it makes the player feel constantly imperiled, even if it's only one enemy taking pot shots. It reminds you that you are not in control, and it forces you to weigh the risks of hunkering down versus the risks of staying mobile. This fragility and lack of limitless ammo makes The Last of Us a nominal stealth game. Joel spends a lot of time tiptoeing up behind the bad guys and choking them out. Sometimes it's bandits protecting their turf, sometimes it's late-stage infected, Clickers, whose fungal growths have made them blind, but also given them phenomenal hearing and an uncanny death rattle of a warning sound. Detection leads to extended shootouts, often with an additional spawn of half a dozen more guys. This makes stealth feel frequently futile, because the penalty for failure is usually more enemies (and more time-spent) than just brute-forcing the encounter in the first place.

There are a few encounters where you can evade the enemies entirely. Very rarely you're allowed to hide from a pack of bandits as they wind through a ruin of cars like a pack of hyenas, or press yourself against a wall as a trio of military men storm past you without checking their peripheral vision. These moments are are so satisfying that it really seems like more of the game should've been about that and far less of it should've been about crouching behind an overturned table and plinking away at ruffians whose thirst for revenge clearly far outweighs their asset management, given how many bullets and lives they waste on Joel and Ellie. Throughout the firefights Ellie scampers around the area, helping where she can (often by hurling a brick into someone's face), and seeming like a person who is part of this engagement instead of a bullet and coin dispenser. This may be because her clambering onto an enemy's back, screaming and spitting profanity as she does, and jabbing her knife into his neck has a more noticeable effect on the battle than if she were there solely to distribute extra carbine bullets. Also because… it looks kind of awesome when she's doing it. And when it's over she emits some hissing whisper of a curse word that vents all her tension out into the room, and into the world, and into the player. Yet, for all the blood and all the swears, the game is rarely crass. This is not The Walking Dead, show or comic, where the ultimate moral is that survival, at any cost, is the only thing of value. Neither does it go with the morally comfortable idea that "sometimes, simply surviving isn't enough." Its characters, even its main characters, do things that are both arguably and explicitly evil. A parent may commit desperate acts in the service of their child. Joel certainly does. This doesn't make evil deeds moral, but it does make them fathomable. The game doesn't go to great lengths to highlight its amorality, as most zombie stories do. It doesn't really bother to point out when it is being clever or gritty. There are power fantasies at play in The Last of Us, make no mistake, but they are rarely the adolescent male power fantasies that video games (and post-apocalypses) usually throw at us.

There is a worry that a game like this needs to be "experienced" (say, by watching it on YouTube) more than it needs to be played. The Last of Us is very linear and very story-based, which doesn't usually lead to multiple playthroughs or complicated gameplay strategies. But the frustration and confusion and anger that builds up inside of us as we wend our way through dangerous combat and clumsy stealth is only replicated, amplified, by the story. Without actively participating in the gameplay the cutscenes might not seem nearly as dire. The Last of Us has some pretty awkward controls. Switching weapons and equipping bricks and healing in the middle of combat is more complicated than we're used to. At times it is definitively "too hard" and deaths come because of cumbersome interface, not to evoke a feeling of helplessness. Often, it feels unfair. Often, reloading to a checkpoint makes you mad. That might be the point. Stories like this -- light on the plot, heavy on the characters -- work especially well in games because we spend hours, sometimes dozens of hours, in a character's skin, through not just the interesting bits, but also the minutiae of rooting through trash cans and picking up salvage. Time-spent can make it easier to empathize with a character in a video game than a character on a movie screen. When they are frustrated, we are frustrated too. When we have spent thirty minutes failing and faltering through combat, our rage makes their rage seem more legitimate. Maybe this is giving the creators too much credit, but the rest of the game feels too purposefully crafted for us write its gameplay off to poor design decisions. As Joel feels harried and disempowered by the plot, so does the player by the game. But as cruel as it is, and as cumbersome, The Last of Us is also kind. The game features such exceptionally graphic violence and it abuses its characters with such pointed focus, that its lighthearted moments are almost impossible to trust. It is a game that knows when you need a break, so it puts its characters on a road trip, or has them crack wise over a stack of dirty magazines, or sticks them in front of a dart board. There is beauty left in the world, where light filters through autumn leaves into sunken basements, their ceilings breached by collapsed highway, their concrete halls converted into impromptu lakes, new homes for schools of fish. As the game gets longer, and the hurts get deeper, so do the breaks, until large stretches are just about walking around, and repositioning ladders, and ferrying about on floating pallets in subway tunnels transformed into rivers, where nature has reclaimed most of what humanity has left behind. The quiet moments last as long as you let them. There is an occasional prompt in the game that dispenses, at the push of the button, some fleeting and non-crucial communication between Joel and one of his companions. There is a high-five button. It only shows up once. I would've liked to see it a dozen more times. I would have liked a whole game made of these prompts. I would've liked to stay in many of these places, the in-between places, for a very long while, because their beauty and calm so naturally convince you that here, and not out there, is where you belong, and if you could just have this then how easy would it be to forget the mission? Don't Joel and Ellie deserve some peace? Don't you deserve some peace? Ellie is fourteen in a world that ended two decades ago, she has never known anything but apocalypse. The apocalypse is her normal. She is foul mouthed and indefatigable because it's hard to imagine anything else for her to be. In a particularly poignant scene -- or not even a scene, really, just a bit of tertiary dialogue spouted out while searching for scissor halves and binding tape -- she tells jokes she's read out of a book, jokes about pizza with punchlines she does not understand. How could she? She's never eaten a pizza. She's probably never even seen one.

And that face! With those baby fat cheeks masked by surly grimace, who could want anything but to protect it, to protect her from a world that hates her, hates everything? But she is resourceful. She is independent. The game walks a tightrope by, at times, treating her like an object, in order to instill a sense of parenthood in its player. We want nothing but to keep her away from all the bad things in the world, but Ellie demands her agency, and eventually claims it, and that twists the knife all the more during the moments where it is taken away from her, or Joel, or the both of them at once. She is so brave, shockingly brave, braver than any of us were at fourteen, braver than we are now, even. She is unthinkably brave, perhaps unknowingly brave, too, and her perils cut us so very deeply. The Last of Us is about the thick skin we've built for ourselves and, underneath that, the places where we secret our hurt. It is about how our morality can be compromised and about how our needs conflict with those of the world. It's about how a pain can build up inside you until the choice between being a good person and a bad person isn't really a choice at all, because all that's left inside you are the echoes of damage that have wound themselves around your heart. There's plenty of ways we expect this game to end, if we follow the road map of six decades of zombie films and comic books and video games. How surprised should we be, then, when it's not about that, any of that: cannibals, bandits, zombies, totalitarianism. Instead it's about grief. It's about what a human is, and about the choices a human might make. The Last of Us doesn't stand on the top of the hill and scream "but who are the real monsters?!" because the truth is it doesn't matter, and never has mattered, and zombie stories need to stop acting like that's the only question worth asking. The characters of The Last of Us may act monstrous -- there is a quick time event for crushing a man's face with your boot that appears with startling frequency -- but its purpose isn't to show us how thin the line between human and monster is, its purpose is to show us that even the monsters may act as they do for very human reasons. |

|

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of Anime News Network, its employees, owners, or sponsors.

|

| Grade: | |||

Overall : A-

Graphics : A

Sound/Music : A

Gameplay : B+

Presentation : A-

+ Fairly original take on the zombie apocalypse with an endearing cast of characters ⚠ Extreme violence |

|||

|

discuss this in the forum (32 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history |

|||