Review

by Carl Kimlinger,From Up On Poppy Hill

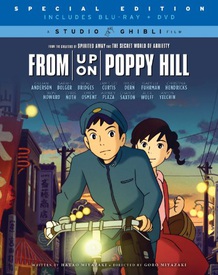

BD+DVD

| Synopsis: |  |

||

The year is 1963. In the port town of Yokohama, pretty young Umi raises signal flags every morning in her garden. Umi's family runs a boarding house, and has done ever since her father was killed at sea. The signal flags are in memory of him. Unbeknownst to her, in the bay a boy named Shun raises answering flags on his father's tugboat. Umi meets Shun when he leaps in protest from the roof of the school's soon-to-be condemned clubhouse. Known to its devoted inhabitants as the Latin Quarter, the clubhouse is to be replaced by a more modern structure. Shun is firmly opposed, and in addition to daredevil publicity stunts, he also runs pro-Latin-Quarter propaganda pieces in his one-page amateur newspaper. One day he asks Umi to help, and the inevitable happens. Unfortunately there are secrets in their pasts that may not allow the inevitable to continue. |

|||

| Review: | |||

Goro Miyazaki's follow-up to his debut, the poorly received Tales from Earthsea, is a modest little film. It's also an immensely charming one. A portrait of youth in 1963 Yokohama, Poppy Hill is a beautifully composed love letter to the era, to the city, and to the joy of being young. It is sentimental filmmaking in the very best sense: moving and deeply nostalgic yet winningly underplayed. The film is simplicity itself. Two young people fall in love as they and their classmates struggle to save a beloved local landmark. It's a family-friendly Hollywood premise that the film molds into something quiet and textured and sweetly real. It lets its leads' feelings drift naturally, maintaining the essential reserve of a Showa romance and leaving it up to us to figure out their relationship. There is no cheap drama, no easy scapegoats or convenient villains. When an anvil drops on Umi and Shun's fledgling relationship, it drops so quietly that only a sudden stiffness in Shun's behavior betrays the dropping. That anvil is the film's one truly clunky contrivance, a hoary bit of soap opera business that even the characters admit sounds like “cheap melodrama.” But even it is treated with sometimes heartbreaking delicacy—plus enough drama-destroying honesty to strip away its soapy aftertaste. The film builds like that, with restraint and deceptive simplicity, to moments of surprisingly deep and honest feeling. It may be a gentle movie, but it isn't afraid to hit your heart. Though it invariably hits it with class and just a touch of poetry. As it does when a beautifully sad dream plumbs the depths of Umi's familial yearning. Or when Umi and Shun share a bittersweet moment while leaving Tokyo. Or, most memorably of all, when independent Umi allows herself to lean on her mother, letting go for one devastating moment of helpless weakness. The Latin Quarter business, on the other hand, allows Goro Miyazaki and his Studio Ghibli crew to indulge their more rambunctious side. The quest to save the ancient building is full of boyish mischief and male ruckus, adding an essential vein of youthful fun. A vein that the film isn't afraid to exploit whenever its tone threatens to grow too grave. As a man (read: a grown boy), the dumb stunts and girl-fuelled idiocy of the Latin Quarter guys strikes a nostalgic cord that resonates almost as deeply as the film's subtler and more profound sequences. What guy hasn't jumped off a roof for attention? Or smiled like a goober when girls scolded him? (Negative attention is still attention, girls.) It's to the film's credit that neither Umi nor the film itself looks down on the boys for their raucous ways. Indeed Umi appreciates their candor and ardor, and while the film definitely finds humor in their filth-living, risk-taking boyishness, it also harbors a marrow-deep affection for them. Arguably the film's very best scene is the one in which the school's boys hold a riot of a debate, only to snap into instant solidarity (and break into song) when the teachers come to check on them. It helps, of course, that the film takes pains to give the hordes of supporting players—both male and female—their own distinct personalities. From Umi's best friend (the no-nonsense daughter of a plasterer) to the uber-nerds of the astronomy club, from the blowhard head of the philosophy club to Umi's girlishly fearless sister, everyone in Poppy feels like they have their own lives and their own stories to tell. It helps too that the film leaves the work of building character to the animators, allowing Umi's purposeful stride and adult poise to say everything that needs saying about her strength of character, or Shun's infectious energy to say everything that needs saying about his natural charisma. Woven through and around this essentially straightforward tale is a meticulously maintained, deeply felt sense of place. In some ways the film is as much about the Yokohama of fifty years ago as it is about Umi and Shun and the Latin Quarter. Exacting attention to period detail and loving appreciation for long-gone rhythms of life and abandoned standards of behavior bring Umi's world to vivid and very human life. Yokohama teems and clatters with the friendly energy of a messily expanding city (most notably during a pair of magnificent downhill races into the belly of the city); Umi's school radiates rustic charm; and the Latin Quarter… well, the Latin Quarter betrays Ghibli's predilection for the fantastical. It's a baroque wonder; an interior shantytown of jury-rigged clubhouses and mazes of stacked junk, twisting their way up cozily crowded staircases and into the depths of the Quarter's several floors, their cluttered balconies connected by rope pulleys and bucket elevators that ferry packages from boy to boy. You can see why the boys love it so. Details pile up as the film moves forward—the feudal posture of Umi's matriarchal grandmother, the small talk of Umi's boarders, the unique lunchtime routines of Umi's school, Shun's old-fashioned romantic reserve, the careening traffic at the city center, the colored smoke from the city's industrial quarter, and uncountable thousands more, all beautifully illustrated and lyrically presented—until we are transported, away from our seats, into the bustling, long-ago Japan of the film's imagination. Satoshi Takebe's lovely pop score, dotted with sweetly old-fashioned songs, supplies the finishing touch on an essentially unassailable production. The sin of GKIDS Poppy Hill dub lays not its casting or its performances. The dub lines up a formidable roster of big-to-medium-name talent, most of whom do perfectly fine work. Anton Yelchin and Sarah Bolger are appropriately restrained as Shun and Umi; Jamie Lee Curtis is predictably solid in the small but pivotal role of Umi's mother; Beau Bridges is perfect as an unexpectedly kindhearted industrialist; and Ron Howard has a lot of fun as the philosophy club blowhard. The problem is with the script. Not that it isn't skillful in its own way. But it treats the film less carefully than the original: imposing unnecessary narration on the opening's wordless survey of Umi's morning routine, for instance, or beefing up the series' message about respecting the past by having Umi blurt it out. It's a blunter instrument than the original, and accordingly deals more damage to the film's delicate dramatic constructs. And that is not acceptable, not in a film as finely constructed as this. GKIDS supplies a choking glut of extras. If you're willing to put in the time, the disc offers up a wealth of revelations about the origins of the film, the history of film's theme song (a gorgeous love ballad), the production of the English version, and the production of the film itself (it was made during the fallout of the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami). There's a good deal of information about Yokohama, both from Goro Miyazaki, who admits to seriously fictionalizing the historical city, and from a travelogue that contrasts current day Yokohama with archival footage from the '50s. There're also multiple tastes of Hayao Miyazaki's notoriously crusty personality, as well as hints of what it must be like to work with/for him. The most interesting material, however, comes from Goro, the son. Specifically the younger Miyazaki's essay, printed in a very nice color booklet, wherein he speaks tellingly of his slack attitude when making Earthsea and his desperation and ulcerating anxiety when making Poppy Hill. He describes wrecking his health, wallowing in doubt, and fervently wishing he was a better artist. His father wrote the film, so he was desperate to avoid being told that “the screenplay was good, but the movie was not.” He needn't have worried. The film born of all that strain bears no marks from it. It is an effortless, magical confection. It is a good film. |

|

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of Anime News Network, its employees, owners, or sponsors.

|

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall (dub) : B+

Overall (sub) : A-

Story : B

Animation : A

Art : A

Music : A

+ A lovely, nicely restrained period love story fuelled by a powerful (if somewhat fanciful) nostalgia. |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (21 posts) | | |||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about Release information about |

||