Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Sanctuary

by Jason Thompson,

Episode CXXIV: Sanctuary

"There's no need for heroes in government!"

—Secretary-General Isaoka

When I was in college, Sanctuary was my least favorite manga. I had a friend who only liked American comics; he made fun of manga for the big eyes, the sentimental stories, all the usual things. There was only one manga he read: Sanctuary. I hated Sanctuary. I hated the cold, realistic artwork, the hard-boiled unsentimental crime plot, and all the scenes of sleazy yakuza guys grabbing women's breasts. (On the other hand, I had no problem with all the scenes in Ranma 1/2 and Video Girl Ai of guys accidentally grabbing women's breasts. Go figure.) When he would make fun of the manga I liked and rub it in my face how much he liked Sanctuary, I would tell him "THAT'S NOT REAL MANGA."

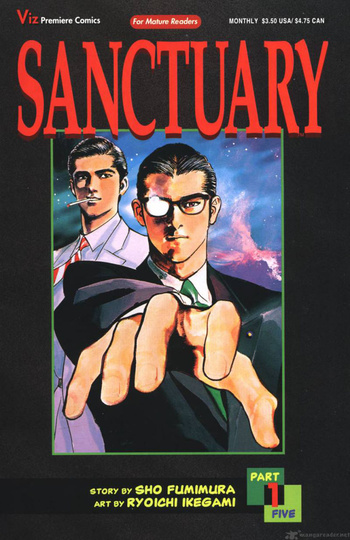

But in the '90s, Sanctuary was one of Viz's bestselling manga, and it's not hard to see why. Americans love crime comics, and Ryōichi Ikegami's art is amazing: his photorealistic mastery of figure drawing and facial expressions makes his manga look realer than life. I think everyone does a double take when they first see it, thinking Is that a photo? How does he do it? Maybe this makes him a good first-time comic artist for people who don't normally read comics because they think they're too cartoony or whatever. My sister, who only ever liked two manga (Maison Ikkoku and Sanctuary), had a Sanctuary poster on her bedroom door, a gorgeous Ikegami painting of the main characters, two very very Handsome Men.

Handsome Man #1 is Akira Hojo, yakuza. Around 28 years old, he's a member of the Hokushokai, a yakuza clan based out of Roppongi, a world of hostess clubs and playgrounds for the ultra-rich. Unlike the stereotypical yakuza who's some tattooed thug or a loser with a bad haircut, he looks hot, has good manners and dresses in expensive business clothes. He'll shoot you with a smile if you cross him (though his underling Tashiro handles all the realdirty work, i.e. the broken glass in the face, the slamming fingers in car doors), but his greatest strength is his charisma. ("A yakuza is a yakuza no matter what he looks like or what lifestyle he leads!") When the story begins, he's only a mid-ranked yakuza, but he's on his way up…whatever it takes.

Handsome Man #2 is Asami, also about 28, who begins the story as the secretary of a member of the Japanese Diet. He's a two-fisted politician (well, politician's assistant); the first thing he does in the story, before he even says anything, is punching some guy in the face for trying to blackmail his boss. Japanese politics is a lot like the yakuza: it's a world controlled by old men who use shady double dealings to maintain the status quo. Asami, like Hojo, is an ambitious young man trying to climb to the top and shake up that power structure. And what is the source of candidate Asami's mysterious funding? Newsflash: it's Hojo. The two (unofficial) hottest men in Japan have a secret alliance, one of them rising through the yakuza, the other through the Japanese legislature—sunlight and shadow!

Only one person knows their secret: Kyoko Ishihara, 27, deputy chief of the Roppongi Police Station. Kyoko, a virgin at 27, has poured all her passion into her work and will do anything to catch Hojo. ("A man's pride is no match for a woman's!") Does she secretly have the hots for him? I won't tell, but here's a spoiler: she keeps his framed photo next to her bed. Regardless, Kyoko does some detective work and uncovers a shocking fact: in 1975, Asami and Hojo were the sons of Japanese families working in Cambodia, where they were caught up in the terror of the Khmer Rouge. Their parents were killed, and Asami and Hojo were sent to a concentration camp, where they ate rats to survive and were only able to escape by sheer luck.

The traumatic experience made a lifelong bond between the two boys, and when they returned to Japan, they made a vow to achieve something. "A part of you that you never let anyone else see…a world of your own, beyond anyone else's power…what we in Japanese call sei-iki, 'sanctuary.'" But for Hojo and Asami, 'sanctuary' is not just a personal goal; it's nothing less than a complete transformation of Japanese society. "The world can't be run by spotty old men forever!" Hojo says. "Do you know the average age of a Japanese politician?" asks Asami. "The young ones are sixty…I want to become prime minister at the age of forty, and fill the cabinet with people in their thirties!" Japanese politics are ruled by wealth and seniority. Career politicians rule thanks to public apathy, and by general disinterest in politics among the Japanese (though Japanese voter turnout is still about 10 percentage points higher than in presidential elections in the USA. Sigh.) Together, Hojo and Asami must fight the system, represented by the toad-like, brilliantly scheming Secretary-General Isaoka, who dominates the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. Will their days in the killing fields of Cambodia give them the guts it takes to remake Japan?

The biggest strength of Sanctuary is that the premise is so crazy ambitious. The intricacies of the Japanese political system may not be familiar to American readers (incidentally, in the original Japanese run of Sanctuary all the names of political parties were changed, but Viz used the real names), but the idea of reforming politics surely is. Asami's political ladder-climbing goes side by side with Hojo's yakuza adventures. They survive by having no fear of death and always being one step ahead. In one early plot, Hojo and Asami threaten a politician by having his thugs grab the politician and…take him to a fancy swimming pool where he sees Hojo flirting with the politician's teenage granddaughter, who thinks Hojo is the coolest. The politician is disturbed at first, but later the politician coldly reassesses and won't give in: "Whether my daughter is raped by some yakuza thug, or married off to some corporate president, what does it matter?" He counter-hires thugs to kill Asami, and they almost do, but they mistake someone else for him and kill the wrong man. The political arena is dangerous too: on his first day in the Diet, Asami gets in a fistfight with the rebellious junior politician Sengoku, who shows up drunk and vomits on the capital steps. When they're not getting punched or shot at, our heroes face prospects even more disturbing than death, like when Secretary-General Isaoka tests Asami's loyalty by having a threesome with him: "A politician can't be afraid to show his ass. Asami, will you take this woman with me?" Another Sanctuary trademark is the dramatic speech (whether political or criminal) that turns enemies into friends, impresses everyone, and blows the audience's (and the reader's) minds. In Sanctuary, the characters almost always talk right towards the camera, like they're talking to the reader. The heroes never lose their cool, no matter how bad things get. In one flashback scene, Hojo has to stab his own hand with a knife to prove that he's worthy to join the yakuza. "Doesn't that hurt, boy?" the yakuza boss asks him. Hojo smiles as he answers, but there's sweat all over his forehead. "It hurts so much I could cry."

But what about the issues? At some point Hojo and Asami do have to explain what their 'sanctuary' means, and it turns out that they have a couple of practical ideas: (1) opening Japan up to foreign labor (so Japanese workers will have to compete harder to stay on their toes), and (2) making Japan more independent from America, perhaps even changing the Constitution so Japan can have an army again. The first idea is still controversial in Japan; the second idea, on the other hand, has been a standard patriotic talking point for decades, at least since Shintaro Ishihara's 1989 book The Japan That Can Say No. Hojo and Asami are nationalists; they want to make Japan stronger, whether it means outproducing the American auto industry or outgunning the Russian and Chinese mafia. Like in Sho Fumimura's other manga Japan (a much worse manga than Sanctuary, despite being drawn by Kentarō Miura), there's a lot of complaining about how the younger generation in Japan today (which would be the mid-'90s) are weak and spoiled and don't have the work ethic of their parents. Not to bust the bubble (economy) of Sanctuary's supposed pro-youth message, but frankly, this sounds exactly like the kind of thing a cranky old man would say. And while Sho Fumimura complains about the complacent old men who have all the power, he's also very respectful to the sufferings those old men underwent when they were young, during World War II and immediately afterwards. The 'Cambodian killing fields' backstory is basically a way of giving Hojo and Asami their own 'war experience' which shapes them into heroes; the only real problem with the old men from WWII is that they forgot the lessons of the war and got lazy.

You want spoilers…? It's a long climb to the top, and Hojo and Asami have to walk over a lot of corpses. But Sanctuary isn't like a typical American crime drama, like, say, Breaking Bad, where power corrupts and pride goeth before the fall. (Remember, Sho Fumimura also wrote Fist of the North Star. He doesn't have a problem with power or pride.) The traditional late 20th century yakuza story, like the films of Kinji Fukasaku, also has an unhappy ending, with corrupt modern elements overcoming traditional yakuza values of loyalty and fraternity. But Sanctuary is more in the spirit of an '80s bubble economy manga; Hojo and Asami are essentially superheroes in suits, like Salaryman Kintaro or Section Chief Kosaku Shima. More often than not, Hojo and Asami make friends with everybody they meet, impressing people so much with their willpower and idealism that everyone switches to their side (even when it makes no sense and goes against their own interests) and the only people who have to die are losers who nobody liked anyway. Indeed, predictably for Ikegami, the few irredeemable enemies in the story tend to fall into just two categories: (1) foreigners and (2) ugly people. Like in Crying Freeman, I spent much of Sanctuary waiting for "the chickens to come home to roost" and the heroes to suffer the consequences of their actions, but it never happens…well, at least not exactly. Maybe Western readers prefer their heroes to be martyrs…but then again, James Bond never had to die for his sins. Of course, James Bond also doesn't give long speeches to his enemies about why he's right and they're wrong and they should join MI6.

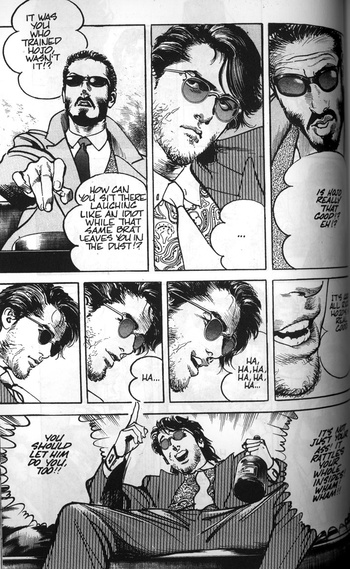

Basically, the story of Sanctuary is of everyone—male and female—falling in love with two superior guys. When I was in school I thought of Sanctuary as "unsentimental" compared to the love-com manga I liked, but actually, it's very sentimental: it's just a macho sentimentality where it's all about the love-worship of powerful men. This is openly acknowledged in the series' best character, Tokai, a tattooed, scarred, long-haired, badass yakuza who was Hojo's aniki before he went to prison. When he's released from jail, Tokai's first line is "Where's the babes?" He's the exact opposite of smooth Hojo: he drinks, he fights, he breaks liquor bottles over people's heads, and he has a habit of raping waitresses in bathrooms ("The quickest way to straighten a woman out is to give her a big thick one!"). However, no matter how many women he screws, Tokai's only true love is Hojo, for whom he has a not-even-disguised homoerotic attraction. "When a dummy like me meets a guy he can't get a handle on, he falls for him just like that. What can I say…I love him!" When Tokai becomes Hojo's subordinate, a police officer mocks him, "Haven't you got any shame, taking it up the ass from that brat Hojo?" Tokai just laughs. "It's good, all right! Hojo's real good! You should let him do you, too! It's not just your ass! It rattles your whole insides! Wham! Wham!"

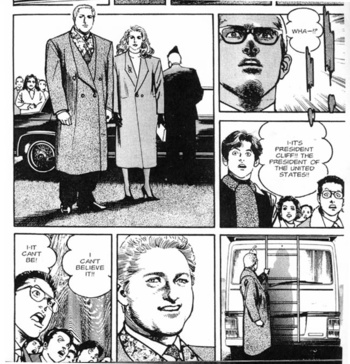

Sho Fumimura and Ryōichi Ikegami collaborated on other manga (also about hot ambitious flawless men) such as Strain and Heat, but Sanctuary is their best one. Many of its arguments about Japanese nationalism and politics are still being debated today, although Japan's weakened economy makes Fumimura's vision of a Japan-dominated future seem more like wish-fulfillment than ever. (But hey, the American economy sucks nowadays, and Americans still love to hear about American exceptionalism too!) In 2009, the Liberal Democratic Party finally lost its domination of Japanese politics. And in 2001, new Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi impressed everyone by being a "maverick" and "young"…but dude, even he was 59 years old. Regardless of how relevant it is, Sanctuary (at least the first few volumes) is a great page-turner with twisty storytelling and beautiful art that's really like nothing else. When will there be another manga like it, another manga for the "non-manga-fan manga fans"? And special bonus: Bill Clinton shows up.

discuss this in the forum (13 posts) |