Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Shigeru Mizuki

by Jason Thompson,

Episode CVI: Shigeru Mizuki

"Outside of the world we know, there exist a hundred thousand other very strange worlds."

—Shigeru Mizuki, Nonnonba

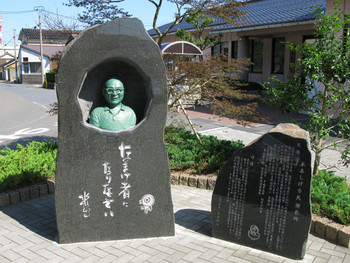

If Osamu Tezuka is the God of Manga, Shigeru Mizuki is the kami. Of course, they're the same words in Japanese—Tezuka's the manga no kamisama—but when I think of Tezuka I think of a wise old man on a cloud, endlessly drawing manga, and when I think of Mizuki I think of a a mythological Japanese creature, a playful spirit, a master of monsters. Shigeru Mizuki is perhaps the world's oldest active mangaka, 90 years old and still going strong, although most of his works have never been released in America. Sakaiminato, Mizuki's hometown, is graced with hundreds of bronze statues of the monsters he drew, a Mizuki museum, and even a statue of the still-living Mizuki himself. It's not hard to imagine people in the future burning incense beneath it, like a Buddhist shrine to a deified mangaka, the artist whose works defined the modern meaning of yokai.

Mizuki's life is like a legend in itself; Frederik Schodt retells it in his book Dreamland Japan. Born in 1922 (six years before Osamu Tezuka!), Mizuki grew up in a remote fishing town in western Japan. An old lady known as Nonnonba, who died in 1933, taught the boy the local superstitions of monsters and spirits. When Mizuki grew up, he went to art school and tried to become a professional painter, but World War II intervened and he was drafted in 1943. He was sent to Rabaul, in the jungles of Papau New Guinea, where the mild-mannered, glasses-wearing boy was continuously beaten by his commanding officers. At one point, Mizuki's entire detachment was wiped out by an enemy attack, and only Mizuki survived. When he returned to base, his superiors reprimanded him for losing his rifle and for surviving rather than dying in combat. In another infamous incident, which later became the basis for his semi-autobiographical manga Onward Toward Our Noble Deaths, another Rapaul-based unit—to which Mizuki was almost attached—was sent out on a suicide mission but returned alive; since their deaths had already been reported to headquarters, they were sent back to the front again with orders not to come back alive. Incidents like this made Mizuki a lifelong pacifist. Onward Toward Our Noble Deaths has lots of dark humor; I hope that the scene where hundreds of soldiers are lined up to see a single prostitute isn't based on real life as well. ("Hurry up in there! Thirty seconds per person, you know!")

It got worse. Mizuki got malaria. Then, his left arm was blown off in an Allied bombing raid. After undergoing surgery in the jungle without anesthesia, Mizuki gradually recovered, an experience which left him with a belief that some spirit force was protecting him and guiding his life. After the war he almost decided to stay in Papau New Guinea with the natives, with whom he had become friends, but instead he returned to Japan. The one-armed veteran worked a variety of jobs, including running an apartment building, operating a pedicab, and drawing artwork for kamishibai "picture-plays." In 1958, when it was obvious that kamishibai weren't able to compete with television and manga for kids' attention anymore, Mizuki adjusted to the times and drew his first professional manga, Rocketman. He soon became a prolific mangaka. He drew some horror: in 1963 he even did an unauthorized manga adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft's The Dunwich Horror, changing the setting of the story to Japan. But he also drew straight-up silly shonen manga, albeit with a working-class, leftist bent: his first big hit was TV-kun (1965), a comedy about a boy who (in Fred Schodt's words) "discovers how to enter his TV set, steal the products displayed on commercials and give them to his poorer, real-world friends."

But Mizuki's first BIG big hit came when he mixed the two: shonen manga and horror. In 1959 he began drawing Hakaba Kitaro ("Graveyard Kitaro"), a manga adaptation of one of the classic kamishibai stories dating back to the mid-1930s. It became popular, but Mizuki had a falling out with the publisher over money, so he left the manga and the publisher hired a hack to continue drawing Hakaba Kitaro for them. (Although according to Takeo Udagawa's awesome book Manga Zombie, Kanko Takeuchi, Mizuki's replacement, actually did a pretty good job.) But Mizuki didn't stop: he took his own version of the story to a new publisher, renamed it Gegege no Kitaro ("Gegege" is a sound FX for a spooky, cackling laugh), and in 1965, it debuted in Weekly Shonen Magazine.

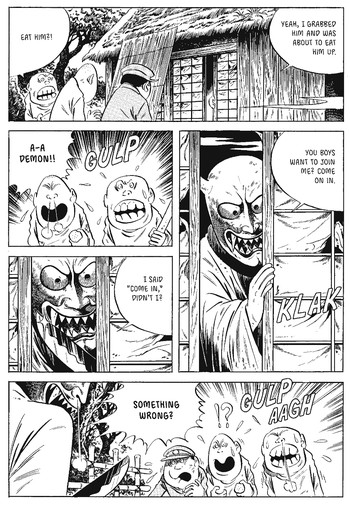

Gegege no Kitaro is the story of Kitaro, a creepy one-eyed boy with strange powers who hangs out in the graveyard and other ghoulish places. Neil Gaiman's The Graveyard Book featured a child raised by ghosts, but Kitaro is no mere human child with a human family to go back to: he's a monster child raised in both worlds. Born to two ghoulish undead creatures, he is the last of the Ghost Tribe, who are apparently not really ghosts but another species, if you wanna get all Charles Darwin about it. (The Japanese definition of yokai isn't too strict on the difference between monsters, ghosts and spirits.) Kitaro's only surviving relative is the final surviving bodypart of his dad, a talking eyeball with arms and legs which occasionally hides in Kitaro's empty eyesocket. Sort of like Jiminy Cricket for Pinocchio, Medama-oyaji ("eyeball dad") advises Kitaro and helps him get out of trouble. Kitaro's other friends include a grubby half-human, half-yokai, Ratman (not Ratnose from Sonny Chiba's The Street Fighter), the catgirl Neko-musume, and various other strange creatures with stranger powers. The original, pre-Shonen Magazine Kitaro stories had been more like horror tales, with Kitaro as the Crypt Keeper who introduces people to horrible scares, but the new shonen manga version was more playful. Kitaro and his pals hang out in places in graveyards, occasionally play pranks on humans, and use their magic powers to fight evil yokai who threaten the human world. Kitaro drew the heroes cute and cartoony (in a funky, definitely-not-Osamu-Tezuka-influenced way), the monsters weird, and the backgrounds super-super detailed, soaked with dark ink, an influence he probably got from horror manga.

In addition to being monsters with weird, vaguely defined powers, Kitaro and his friends have one other thing in common which is unusual by modern manga standards: they're all outcasts on the margin of society. After all, humans don't believe in monsters (a recurring theme in Kitaro is dumb adults who only don't believe in the supernatural). And Kitaro doesn't really have any human kid friends to make things more 'accessible' for the reader, and he doesn't spend much time enrolled in human school as a mysterious transfer student, or anything like that. The theme song of the original GeGeGe no Kitaro anime, which started in 1968, goes like this…

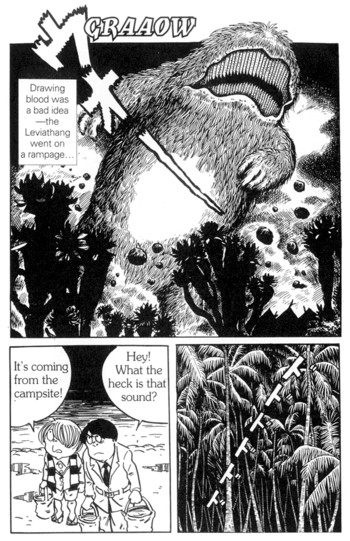

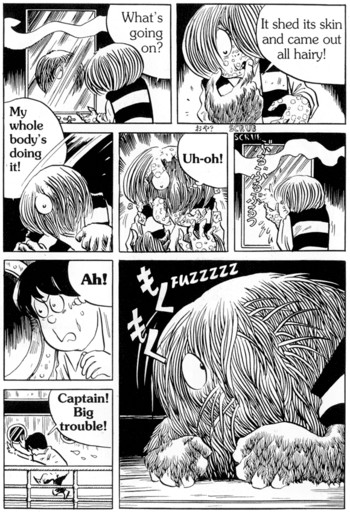

In the morning we're half asleep in bed

So much fun at monster school

Never a test, never a quiz

…accompanied by about a thousand "ge ge ge ge"s. Monsters don't go to human school! (Or ninja school, or magic school, for that matter.) Monsters aren't a part of your System, mannnnn! Kitaro is a kid, but he's also a weird wandering rebel freak, with just his dad to keep an eye on him. (I'm sorry. That was awful.) When not fighting monsters, he sometimes fights against corrupt adults, like in the story "The Leviathang," in which an evil scientist tries to capture a prehistoric whale-creature and ends up injecting Kitaro with prehistoric blood which turns him into a giant hairy monster. It's typical Kitaro chaos, with a happy ending. That particular story was influenced by the kaiju giant-monster boom (Godzilla etc.), but mostly, Gegege no Kitaro is about yokai. Mizuki uses his knowledge of Japanese legends and monsters to fill the story with weird beings: the "eight million gods" of Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away and Lafcadio Hearn's Kwaidan. Plus, Mizuki researched other cultures and threw in their monsters as well, using creatures from the fairy tales of Europe, South Asia and other places, which he visited once he had enough money enough to go there. (He even returned to Rabaul, where he lost his arm, to see the locals he had befriended once again.) But above all, he draws the monsters of Japan. Haunted umbrellas, living walls, giant flaming wheels, monstrous snakes and frogs and two-tailed cats…all kinds of spooky things creep and crawl through Gegege no Kitaro.

Is it any wonder it became a hit? Mizuki's art style (cute monsters, funny faces) are an influence on the work of artists as different as Akira Toriyama and Hideshi Hino. Osamu Tezuka's Dororo and Kazuo Umezu's Cat-Eyed Boy are also clearly inspired by (or: ripped off from) Mizuki's "monster child" stories. Mizuki's work was so popular he started a yokai boom in 1960s Japan, sparking new interest in the original myths and monsters he took his ideas from. In the '70s, Mizuki drew a lavishly illustrated "yokai encyclopedia" which is still considered one of the primary resources on the subject. Even modern manga like Yokai Doctor, Natsume's Book of Friends, and Nura: Rise of the Yokai Clan show the influence of Shigeru Mizuki's yokai. Mizuki accomplished the greatest thing a fan could accomplish: he started out drawing Gegege no Kitaro as a tribute to the monster myths he loved, and today, Gegege no Kitaro is better-known than the original source material he based it on.

And at some level, it seems, Mizuki actually believes this stuff exists. Mizuki went on to draw many other, non-Kitaro manga about diverse topics—a manga history of the Showa Era, a biographical manga about Adolf Hitler—but he always returns to yokai. It's like they're a part of his spiritual beliefs deep down. In 1977 he wrote a story about his childhood, Nonnonba, which he adapted into a manga in 1992. It's an amazingly polished and beautiful manga for an artist who, at the time, was 70 years old.

Nonnonba tells the story of Mizuki's childhood and his friendship with old lady Nonnonba, the teller of ghost stories. In some ways, young Shige (the young Mizuki's alter ego) is like every other middle-class kid in 1930s Sakaiminato: he spends hours after school fighting mock battles with the other kids, kicking the crap out of one another in two teams in a faintly disturbing foreshadowing of the War. But he also has an introverted, artistic side: he draws, he collects tree roots and animal bones, and he stares for hours at Buddhist paintings of heaven and hell. Most of all, he listens to the teachings of old lady Nonnonba, an old spiritualist whose main source of income is being paid to pray for people who are sick. She teaches him legends about monsters: "When a nonbeliever prays only at their convenience, an otoroshi drops down from the shrine gates!" "Cats show up as spooks called nekota after they die. And cats that lived longer than ten years turn into nekomata. They have two tails!" "Akaname is as a red monster who comes at night. She looks like a child except she has a looooong dirt-licking tongue!" He's scared, but he's also filled with awe and wonder at unknown things and the nature of existence. School is much less fun than Nonnonba, particular since even the school is becoming influenced by Japan's growing wave of patriotism and militarism: when he's late his teacher shouts "Japan is isolated and outshone internationally! What kind of son of the empire are you showing up late every day when our very survival is being threatened?!" The antiwar message of Nonnonba reminds me a bit of Barefoot Gen, but much subtler.

Then a new girl moves into town, Chigusa, an invalid whose time is mostly spent with bedrest and doctors. Mizuki makes friends with her, even though she's from the big city and doesn't believe in small-town superstitions. Death isn't too uncommon in this poor rural area, and Mizuki starts to think about the spiritual side of yokai. If yokai are real, might heaven not be real as well? In this manga, it seems like yokai are real, although you can never be quite sure it's not a dream or a hallucination. Mizuki makes friends with a yokai, the big-haired azuki-hakari, and he asks it deep questions. "A moment is an eternity, an eternity a moment," azuki-hakari cryptically answers. As Mizuki grows up, he deals with love, sorrow and the ostracism of his classmates, and Nonnonba and the yokai give him advice. It's all about spirits, Nonnonba says; the emotions he feels are actually the spirits of people in his heart. "As time goes on, you'll gather bigger and heavier spirits in your heart. But your heart will grow to bear that weight, and that's how you become an adult."

Spirits, monsters, yokai, religion, fiction, fact, everything mixes together in Mizuki's fascinating manga. It drives me crazy how little of his stuff is available in English; out of the approximately 1 jillion volumes of Gegege no Kitaro, only three short Kodansha Bilingual volumes were ever translated, and they're all out of print and hard to find. Luckily, Drawn & Quarterly recently released translations of Nonnonba as well as Mizuki's antiwar manga, Onward Toward Our Noble Deaths. From even this small sample of work, I get a picture of Mizuki as an old leftist hippie, a cheerful old man who believes in monsters and mysticism, who is opposed to war and authority, and whose big-headed kiddie characters have been adapted into five anime series and tons of live-action shows and made him super bank. He's like the Charles Schulz of Japan, only nicer. Even his wife likes him so much she wrote a novel about their life together, Gegege no Nyobo ("Gegege's Wife"), which was adapted into a film and a drama series. Life is basically good, even if sometimes sad things happen. People are basically good, even if sometimes they're foolish and blinded by power. Monsters are real. Even if this means the Dunwich Horror is real too, I could totally get behind living in the world of Shigeru Mizuki's manga.

discuss this in the forum (9 posts) |