Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Eagle

by Jason Thompson,

Episode LXIII: Eagle

The son of an immigrant works his way up by his bootstraps, goes to law school, and then goes into politics. After fighting with Hillary Clinton in the primaries, he becomes the Democratic presidential nominee, and goes up against an old white Republican in the presidential race. In a political contest focusing on America's foreign wars, he steps closer to a dream some people thought was impossible…becoming America's first non-white president.

If this sounds familiar, it's the plot of Kaiji Kawaguchi's manga Eagle: The Making of an Asian-American President. Viz was so excited about this manga that they rushed it into production in time for the 2000 presidential election, making the then-unusual decision of releasing it as monthly graphic novels (albeit small ones of 100 pages each) and 400-page omnibuses instead of tiny monthly comics. Politics junkie Carl Horn, now the #1 manga editor at Dark Horse Comics, put his life's blood into the edit, using all his knowledge and research to make the English rewrite as realistic as possible. Yet despite the parallels to Barack Obama, and five Eisner Award nominations, Eagle is almost forgotten today, and no one has ever tried to reprint it.

Eagle is a look at an American presidential race from a Japanese perspective. Takashi Jo, a young journalist who never knew his father, returns home in Okinawa after his mother unexpectedly dies. But the funeral is barely over when he's sent out on assignment for the Maicho Shimbun newspaper: to go to America to write a piece about Kenneth Yamaoka, a Japanese-American Senator running for president. Yamaoka seems like the perfect candidate: a star quarterback in college, a Vietnam war vet and a successful lawyer. He's a family man too, married to wealthy New England heiress Patricia Hampton, and his son Alex and his adopted daughter Rachel are close to Takashi's age. Tall, handsome, well-spoken and able to keep eating no matter how many fundraiser banquets he's invited to, he seems like the perfect candidate. Takashi, who's new to American politics, is surprised when the candidate grants him a private interview.

And then Yamaoka drops the Darth Vader bomb: "Takashi…I'm your father." DONNNNN!!!, as they say in One Piece. Yamaoka reveals that he had an affair with Tomiko, Takashi's mother, while he was stationed in Okinawa as a serviceman. Now that Takashi knows the truth, if he wants to, he could surely reveal it and end Yamaoka's presidential campaign. But the inscrutable candidate seems to trust that Takashi won't betray him. Quite the opposite, the young man can't bring himself to betray his father until he finds out even more. Takashi follows his father on the campaign trail, doubting and hoping, trying to figure out the answer to the main question of the series: who is Kenneth Yamaoka? What was Yamaoka's reason for abandoning Takashi and his mother? Is he the idealist that the world knows on the surface, or a ruthless, Machiavellian power-politician? Is he America's only hope, or the devil himself?

Kaiji Kawaguchi, the author of Silent Service, Zipang and recently the time-travel manga Boku wa Beatles, is a seinen mangaka who does stories about history, politics and war. He's kind of like the Tom Clancy of manga, but Eagle (the "making of…" subtitle was added for the American edition) is his only work that's been translated, except for a rare Kodansha Bilingual edition of Zipang. In an interview in the back of volume 2, Kawaguchi explains that he was inspired by The War Room, the documentary film set behind the scenes in Bill Clinton's 1992 presidential campaign. Eagle attempts to explain the weird world of American politics (particularly the confusing electoral system), and also to channel the excitement of an American political race, something with no real parallel in Japanese parliamentary politics. Armed with plenty of research and location photos, Kawaguchi takes his reader on a tour not just of American politics, but of America the country: Sakura Square in Denver, the statue of Nathan Hale on the Yale campus, Miami, Florida's Little Havana, the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago. It's an American travelogue, combined with a story of power and ambition, sex scandals and family secrets.

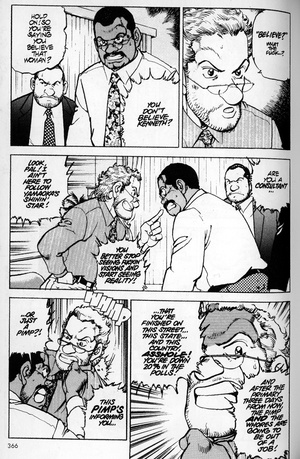

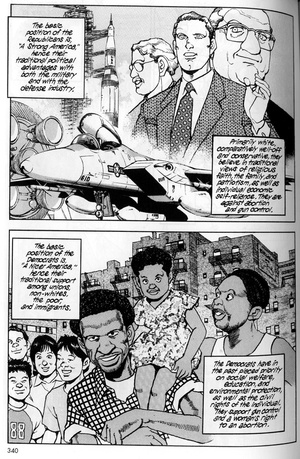

But does it have politics? Oh yes it has politics, and hell yes, Kawaguchi takes sides. Yamaoka is a Democrat, standing up for liberal values like peace, gun control, and unions. The Republicans are the bad guys—although really, the Republicans don't even show up that much, since most of the comic is about Yamaoka's primary battle with his Democratic rivals. When the story begins, Yamaoka is considered a long shot to get the Democratic nomination; his main rival, the Vegeta character, is vice president Albert Noah. Any resemblances to Al Gore are clearly intentional; in the Japanese edition, his name was originally "Albert Nore" but editor Carl Horn changed it, in his own words, because "Albert Nore sounded a little too Mad Magazine." Al Noah is depicted as a cool aristocratic policy wonk, a blueblood in contrast to Yamaoka, a man of the people. Another deadly rival is the first lady, Ellery Clinton, the wife of President Bill Cliff. Ellery—I have no idea who this is a caricature of, honest—is an ambitious politico with a hunger for power. "There's a compelling force in this house. You can feel it in your body…it comes from politics itself! It's erotic…bestial…I thrive on its brutality!" The Republican candidate, Robert Grant, the Freeza character, is a 68-year-old ex-astronaut with ties to the military.

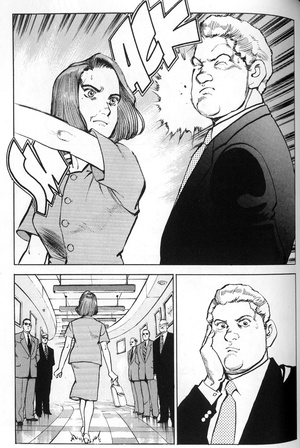

Yamaoka works his magic charisma against these and other opponents, in public debates and backroom dealings, while Takashi watches from behind the scenes. Kawaguchi is fascinated with the workings of the political war room, of staying up late chugging coffee, manning the phones, figuring out strategies, etc. One of Yamaoka's first victories is to enlist the help of George Tuck, a scruffy super-campaign-advisor, apparently based on Dick Tuck. But like any shonen manga opponent who's badass when they're an enemy but instantly turns useless when he becomes your ally, George spends a lot of his time just reacting to Yamaoka's recklessness. In Kawaguchi's version of America, most political battles are won by Yamaoka himself meeting one influential person (in Eagle, politicians don't seem to have handlers or bodyguards) and convincing them that he's the right man for the presidency. He goes to New York to get the endorsement of NYC mayor Gilbert Blackburn; he goes to Texas to get the endorsement of Don Taylor, a good ole' boy ranch owner. ("I need you to contact all your union members before the polls open! I want the vote from every farmer, rancher, canner, and meatpacker we've got in the Super Tuesday states!") It seems unrealistic (or does it?) that these power-brokers can supposedly convince millions of people to vote for Yamaoka, but maybe you could say that Kawaguchi is using them as a microcosm of the demographics they represent. As Kazuo Koike said, "manga is about characters," and it's easier to show politics as a conversation between two people than as numbers on a poll. And Yamaoka has a way of convincing people. "I felt it from the moment I met him. He was different from anyone I'd ever known…" says his wife Patricia. "Y'talk t'him, y'believe in him!" say the Texans.

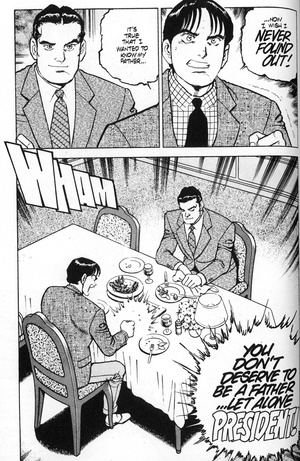

So then what's up with the whole having-an-affair-and-abandoning-his-son thing? The answer, and the key to Yamaoka's whole personality, seems to lie in Yamaoka's traumatic experiences in Vietnam, which took him to the darkness, like the dark heart of America itself. His own brother died there, and he himself survived by "pure will"…and by becoming a killer. "These hands are stained with the blood of mothers and children," Yamaoka confesses to Takashi with a smile. DAMN! "The truth of the matter is that war is murder. Their holy wars, our wars for peace—murder. Those whose job it is to lead their country into it are also murderers." Are these the words of an idealist, or a complete cynic? Early in the manga, Takashi thinks he's figured out that Yamaoka is a good guy at heart, but when he tells his thoughts to Yamaoka, Yamaoka just mocks him. Takashi gets mad back. "You're not fit to be a father, let alone the president! You're a heartless bastard!" As Takashi becomes closer to Yamaoka's oblivious family—his stately wife, his sweet daughter, his impulsive son—he starts to wonder about his own family. What really happened to his mother? He and his mother are the only people who know the secret that could stop Yamaoka's presidency. Did she die naturally…or was she killed?

2000 long, rambling pages of sex, espionage, politics and traced photographs—this is Eagle. The manga challenges some tough issues, including race; it isn't blind to the troubles that an Asian-American candidate would face. As one character says to Takashi, "If he does become president, this country will never be the same. The American people are a melting pot of many races, but the American presidency? 'Eisenhower' is about as funny-sounding as their names have ever got. No 'skis'…no 'steins'…let alone anything like 'Yamaoka.' Two hundred years since George Washington, and in all that time there's been exactly one president who wasn't a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant. And look what happened to him." Yamaoka's odyssey is also the odyssey of Japanese-American immigrants, and as Takashi traces his father's path from Seattle to the nomination, he learns something about the history of Japanese-American communities. It was through Eagle that I learned about Ralph Carr, governor of Colorado from 1939 to 1943, and one of the few politicians who spoke out against the incarceration of Japanese citizens during WWII. Perhaps Eagle's view of race in America is still a little optimistic, but looking at it from 2011, Yamaoka's journey doesn't seem impossible.

Eagle was one of those manga that people love to love but don't love to buy; despite good reviews, its sales always sucked horribly. Perhaps readers were turned off by the slow pace, or perhaps it's just that seinen manga never sells. But Eagle also has some real problems. Kawaguchi's big ambitions mean he has to be held to big standards; drawing an entire manga about American politics isn't as easy as just giving Barack Obama a cameo in Air Gear. For all the ways that Eagle gets American politics right, there are ways that it's absolutely, fall-on-your-face wrong. Many issues that are political hot buttons are never mentioned at all, particularly all the issues related to the religious right: abortion, gay marriage, religious issues in general. Some of this may be because Kawaguchi was writing the manga in 1997-2001, with the Clinton years as his model, before the Bush years gave a huge boost to the religious right and pushed all these issues into the forefront. (Gay marriage, for instance, wasn't a major political issue until about 2004.) But it's probably also because these issues are less of a big deal in Japan, and Kawaguchi simply thought his readers wouldn't be interested.

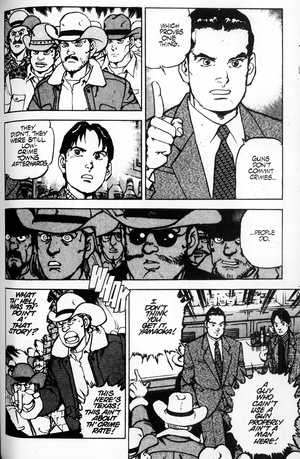

Another problem with the manga is that, at times, it's just ridiculous. (WARNING: SPOILERS.) We always see Yamaoka from the perspective of Takashi or another character—we never really see inside his head—and as a result, Yamaoka never really develops a human side, no matter how much we find out about his past. He's the archetypal manga hero who everyone says is charming and brilliant, even though we, the reader aren't always convinced he's so charming.In one unbelievable scene he goes into a honky-tonk bar in Texas and convinces the cowboy-hat-wearing cattlemen that America needs stricter gun control laws. Reading this scene and other like it makes me angry, not because I have strong feelings about gun control either way, but because it's illogical to the point of stupidity. This could never happen. In shonen manga, it's a convention of the genre that you can awe people into agreeing with you, but in the real world, there's no 'perfect' argument in favor of gun control, or most other issues. Americans can't agree on objective scientific data, let alone politics. (I don't know why I find this shonen-ness so much more annoying in Eagle than in The Legend of Koizumi, but I suppose it's because Eagle doesn't have a mahjong battle against Hitler on the moon.) In places the manga reads like it was storyboarded visually and the text came later ("In this panel, Yamaoka gives awesome speech. Write speech ten mins. before deadline"). Sometimes Eagle's political speeches are good and believable, partially thanks to Carl Horn's rewrite, but other times they remind me of Douglas Copeland's description of Japanese comics in Microserfs: "The characters all look as if they're saying unbelievably important things — talking to God and the Wizard of the Universe — but when you translate them, all they're really doing is making belching noises."

Since he is written as a manga hero and not a realistic portrait of a human being (i.e. he's more Section Chief Kosaku Shima than Don Draper), Yamaoka never really has to answer for the contradictions in his character; he gets to have it both ways. Other characters, such as Takashi, and Al Noah, end up being much more sympathetic. But Yamaoka is an idealist and does have one great dream, which he reveals after the Democratic nomination, setting into motion the final act of the story. At a memorial service at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Yamaoka says "Vietnam was not a 'war'. I believe it was an act of barbarism committed by a selfish nation." The veterans on the National Mall are shocked and angered, but they're even more shocked when Yamaoka continues his speech on national TV the next day. "First, over the next eight years, I will order that all U.S. bases abroad be shut down. Second, unless the lives of American citizens and the territory of the United States itself is under threat, it will be the policy of my administration to forego any future U.S. military action. My administration will work to make the United Nations what our ideals meant it to be…a true collective security organization for a world of freedom…that transcends any need for military nationalism…including our own! In other words, I want to dismantle the military-industrial complex!"

This speech is Kawaguchi's idealism talking, not just Yamaoka's. With this big reveal, Yamaoka is revealed to be a character along the lines of Captain Kaieda in Kawaguchi's Silent Service, the nuclear submarine captain who goes rogue and declares that his submarine is an independent state. In both this manga and that, the hero is driven by a desire to stop American military intervention in foreign countries (and in both manga, the United Nations is presented as a shining, humanitarian alternative). The theme, of course, is very much on the minds of Japanese readers, since Japan is host to American military bases which aren't entirely welcome there. It's foreshadowed at the very beginning of the manga, when Takashi tries to throw his mother's ashes into the sea off Okinawa, but they are blown back into his face by the jetblast of an American fighter plane. In a nod to realism, after Yamaoka's speech the phones start ringing off the hook at campaign headquarters, with people accusing him of being a traitor, but Yamaoka perseveres. In typical Yamaoka style, he even manages to have it both ways, telling American military contractors that he'll help them transition into their new role as military suppliers to the United Nations peacekeeping forces. (Except of course they'd surely only be making a tiny fraction of the profits they made before, and…oh, I give up.)

Whether or not you believe that the US should end its foreign wars, this plot development is ridiculous; a presidential candidate who said something like that would soon be an ex-candidate. Well, no one ever said manga had to be realistic. Even if the politics and the candidate are wildly idealized…and even if the last volume feels frustratingly rushed, with the Republican candidate almost like an afterthought…Eagle is worth reading for the experience of seeing America through an unfamiliar mirror. It's got a family drama too. "I consider Eagle to be at heart the story of a family," Kawaguchi has said, and he's right. I haven't even mentioned the love story.

But it's also true that Eagle has not aged well. Its politics are based on the Bill Clinton era, and not just because of Bill and Ellery. It's set in that time between 1992 and 2001 where America was at a height of prosperity, with the Cold War over and no obvious replacement enemies, a time when Japanese liberals like Kawaguchi (and some Western liberals) could dream that the US might focus on peace. But today, 10 years later, the US military budget is bigger than ever, and the great unending war on everyone's mind isn't Vietnam. Today, it's not hard to picture a candidate from a non-white immigrant background getting questioned about what country he's loyal to, something Kawaguchi was too naive or noble to even imagine. Today, Eagle is a manga about history, not current-day politics; although to be fair, it was always more about the feeling of working on an American political campaign more than it was about actual American politics. If you can't find this manga in a bookstore or library, the next best thing is volunteering for a local political campaign. (Actually, that might be even better than reading this manga.) Hopefully Eagle won't be the only Kaiji Kawaguchi manga ever translated in English in a nice omnibus edition.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (41 posts) |