Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Wild 7

by Jason Thompson,

Episode LVIII: Wild 7

"The Wild 7-- a super squadron of elite cops -- operate above and beyond the normal reach of the law! These former bad guys go after murderers and crooks who hide behind the power of corrupt politicians!"

I've never been a big fan of Speed Racer, except for the techno remix of the soundtrack from Alpha Team. It's one of the most successful anime ever brought to American TV, but it never played on TV where I lived, and the few times when I did see it, it was localized into English so well, it felt like the kids' cartoon that it was. Still, its hyperactive style and giant-eyebrowed hero are a link to the dusty days of 1960s shonen manga, when men were men even if they wore white pants and red socks, and when shonen manga was still mostly about exaggerated versions of "real" things, like sports and samurai and crime. But I can't think of Speed Racer without thinking of another '60s story that I like much better, Mikiya Mochizuki's Wild 7.

There's not actually much connection between the two: Speed Racer is an anime about a boy with a racecar (the manga published by DMP is a Japanese adaptation of the anime) and Wild 7 is a manga about a group of rogue motorcycle cops who chase down crooks. But Mikiya Mochizuki, the creator of Wild 7, worked as an assistant to Speed Racer creator Tatsuo Yoshida, and the two properties have similar character designs, similar crazy action and a similar generational feeling, coming out within two years of one another. There the resemblances stop. Peter Fernandez, who brought Speed Racer to American TV, used to boast that due to his edits, nobody ever died in the English version of Speed Racer (although I guess he didn't count drivers of all the cars that plummeted off 50-foot cliffs); but fat chance ever editing the deaths out of Wild Seven. Gun battles, brutal beatdowns and dubious morality are packed into every chapter. It's one of the most violent children's manga imaginable, a manga that feels like someone shouting at readers "Hey! Manga aren't just for kids anymore!" before pistol-whipping them in the face.

Wild 7 (no relation to the 2006 American movie of the same name) is the story of a band of seven motorcycle cops who hunt criminals that the law can't touch. Answering only to a shadowy ex-policeman who funds them with mysterious sources of income, they're antiheroes one and all, all of them with a dark backstory and deadly talents. ("To qualify for the Wild 7, you must first, be a villain and second, have a worthy skill.") Hiba, the leader, is an ex-reform-school kid. Don ("oyabun" in the original Japanese) is an ex-yakuza. Backfire ("Ryogoku" in the original Japanese) is the buck-toothed, nerdy demolitions expert, whose bike has a rocket launcher for a sidecar. Hippy Tom, the beardy strongman with John Lennon glasses, is a would-be revolutionary who had to go on the lam after blowing up a bunch of planes at one of America's Japanese military bases. Each of them has their special motorcycle and their special gun, and they aren't afraid to use them. They drag crooks behind their bikes for punishment, and dangle them over the edge of skyscrapers (like Batman in Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns) to extract a confession. They have to be tough, because in the world of the Wild 7, the crooks control the politics, the courts and the media. In the first chapter, Hiba chases down an oily criminal who just got out on bail, and pulls up next to the guy's limousine, pretending to be a traffic cop. "I've come to erase you," he tells them. "You mean arrest, not erase," say the crooks, laughing about how they're just going to pay some stupid traffic ticket and get off scott free. "No—I meant ERASE!!" Hiba shouts, and whips out his gun and blasts them to pieces.

Of course, Hiba doesn't spend all his time shooting bad guys in cold blood. In his spare time, the boyish assassin hangs out at a coffee shop run by Iko, a cute girl whose panties are occasionally visible, and her little sister Shinobe, who has hair like Cindy Lou Who in The Grinch Who Stole Christmas. Iko has a crush on Hiba, and Shinobe teases her about it, goofing up the manga with her scampy-little-kid hijinks. Another regular at the coffee shop is Makoto, a little boy whose dad is a policeman. Makoto's dad is the kind of cop who's loyal to the system, who tries to do things by the book and ends up getting betrayed by his corrupt superiors and beaten half to death by dirty crooks. Hiba respects Makoto's dad, and even though he's a killer, he has his own sort of moral code. He occasionally tries to convince the leader of Wild 7 to let him do things more humanely, but the boss always shuts him down. ("Why not let him confess and give him a chance to mend his ways?" "What on earth are you thinking?! How dare you defy my orders! Strike them off the face of the earth!") Most of all, he respects friendship: the friendship of his fellow Wild 7 members who share a sense of honor and a desire to make a better world by killing bad guys, or doing whatever it takes.

Wild 7 was a super hit in Japan; it went on for 48 volumes from 1969 to 1979, and was followed by many sequels and spinoffs, including an anime made as recently as 2002. In America, it wasn't so successful; just six volumes of the original series were translated by ComicsOne in 2001. (Mochizuki was annoyed that ComicsOne changed the name of some characters, like turning "Happyaku" into "Otto" and "Hebopi" into "Hippy Tom".) There's a lot more information (in Japanese) at the amazing fan site wild7.jp, which talks about all of Michiya Mochizuki's manga in many genres: military, soccer, boy detectives, samurai drama, crime. In addition to being a mangaka, Mochizuki worked as a soccer coach and a construction worker. His resume is like a snapshot of shonen manga in the '60s, and boy, his heroes have big eyebrows.

And yet it's the politics, not the art, that really makes Wild 7 a period piece. To quote Lone Wolf and Cub creator Kazuo Koike: "The '70s in Japan was an era rife with student protests…There was a lot of resistance and overall, people were very angry. The mood in the air affected manga creators as well in the subject and content of their work." Wild 7 shares this anti-authority feeling, and like Koike's works, it's not a straightforward leftist moral where hippies and activists are good and cops and politicians are evil. In Wild 7, peaceniks and pacifists are just as likely to be corrupt (or at least misguided) as anyone else.” In one scene, the "good" policeman tries to get the riot police to support him in an attack on the criminal headquarters, but the head crook just laughs and turns on the TV, revealing that all the riot police are busy dealing with protesters at the nearby college campus. "I created the protest to keep the cops busy! I'm in control of the demonstration!" Does that make Wild 7 right-wing? Well, maybe and maybe not. Like Hippy Tom, the heroes' sympathy is with the activists; in another scene, they refuse an order from their tyrannical boss to attack a gang of protesters. In fact, their boss is obviously evil, and it seems like it's just a matter of time before the Wild 7 rebels against him too. It's the standard nihilistic dilemma seen in so many action movies: work for The Man who gives you tricked-out motorcycles and guns and high-tech toys, or rebel against him too and just blow up EVERYTHING?

The mixture of manly friendship, tons of bullets flying everywhere, and bravado in the face of certain death reminds me of the films of Sam Peckinpah, whose The Wild Bunch came out just a few months before Wild 7. Another movie which feels similar is the original Dirty Harry, with Clint Eastwood as the vigilante cop, but it came out in 1971, two years after Wild 7. Still, both of them channel the same anger against the chaos of the 1960s: the desire for rebellion mixed with the desire for law and order; anger against the corrupt authorities mixed with anger against the lowlife scumbags dealing drugs on your street corner. (Incidentally, the makers of Dirty Harry later tried to back away from glorifying vigilante violence; in the 1973 sequel Magnum Force, the bad guys are a death squad of rogue motorcycle cops who execute criminals without trial. Dirty Harry vs. Wild 7?) But Mochizuki wasn't just inspired by American movies; one of his big influences for Wild 7 was the Shinsengumi, the famous special police squad which kept the peace in Kyoto during the Meiji Era. ("I am a Shinsengumi otaku," says Mochizuki on wild7.jp.) The Shinsen-gumi fought for a doomed cause—the Shogunate—but like the Wild 7, the morality of their cause doesn't matter as much as their honor and loyalty to one another. Unlike Lone Wolf and Golgo 13, those other famous manga assassins/antiheroes from around the same time period, the Wild 7 suffer a lot, proving their awesomeness by the amount of blood they shed (their own, not just other people's).

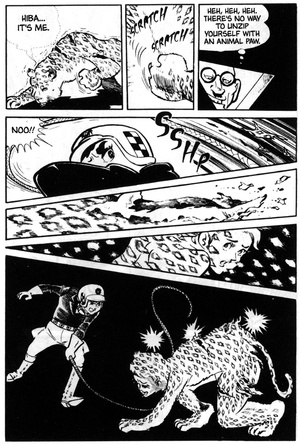

The weird thrill of Wild 7 is seeing the guns-blazing deadly violence mixed with boys' manga silliness, such as the bad puns, the villains' booby-trapped headquarters, or the Biker Knights who dress up in Medieval armor and impale their enemies on sidecar-mounted lances. Gory death, cynical adult political commentary, and afterschool-cartoon violence (such as Hiba's special four-wheeled motorcycle that can drive up walls) coexist cheerfully. Oh, and did I mention the sex? Well, maybe that's an exaggeration; there isn't really any sex in Wild 7, at least not in the translated volumes. But there is that scene in volume 3 where the villains kidnap Hiba's hapless girlfriend, Iko. When Hiba comes to their hideout to save her, the villains gag Iko and put her inside a leopard suit, unable to do anything more than crawl like an animal and moan pitifully. Thinking that she's a real leopard, Hiba grabs a whip from the wall and lashes Iko over and over while the villains watch and drool. "The more she tries to get near him, the more he'll whip her. Yeah, yeah, whip her some more! Ha ha ha ha…!"

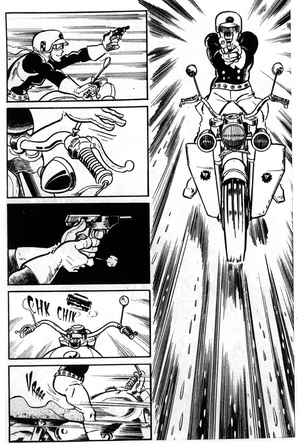

So, Wild 7: arguably inappropriate for all audiences, but like Sam Peckinpah and Dirty Harry, you can enjoy it just as a good story with lots of guns and bikes and heroes with tragic pasts. Also, Mochizuki draws great action. His battle and chase sequences are still exciting forty years later, with lots of explosions, motorcycle stunts, incredible handgun shots and narrow escapes. His cinematic style, as well as his occasional penchant for sadism and damsels in distress, was an influence on the manga of Hirohiko Araki (JoJo's Bizarre Adventure). For those who like detailed schematic closeups of motorcycles and guns and (to a lesser extent) military equipment, it's got that too, showing the influence of Yoshiyuki Takani and Shigeru Komatsuzuki, some of Japan's greatest 20th-century illustrators of real and imaginary military hardware. In fact, of all Mochizuki's many untranslated manga, the one I'd most like to see is Saizensen ("Front Line"), his 1964 shonen manga based on the true story of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The 442nd were Japanese-Americans who volunteered to fight in the European battleground in World War II rather than be imprisoned in internment camps like most other Japanese-Americans at the time; I wonder how Mochizuki handled the material. As for Wild Seven, it's one of those crazy classic manga that is way too long and old to be translated, except perhaps by something like j-comi.jp, whose founder Ken Akamatsu has been talking about using machine translation and google ads to get old out-of-print manga online. Who knows? Until then, the ComicsOne ebooks are still easy to find online, and worth checking out, if you don't mind the low image quality.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (4 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history