Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Raika

by Jason Thompson,

Episode LIV: Raika

For this week's column about obscure, underappreciated and classic manga, I'm going to talk about…NARUTO! No. Not really. I'm going to talk about Yu Terashima and Kamui Fujiwara's Raika, which is sort of like Naruto's grandfather's cousin. Probably Fujiwara's second most famous manga (his only other translated work is Hellhounds: Panzer Cops, written by Mamoru Oshii and later adapted as the anime Jin-Roh), it ran from 1987 to 1997 in Japan, and had a brief run in English in 1992-1993.

Most manga set in historical Japan are set in the Meiji or Tokugawa eras, but Raika takes us way, way back, to a time before Japan was Japan. It's set 1800 years ago in the realm of Queen Himiko, the semi-mythical founder of Japan, then known as Yamatai. Technology is primitive; the great hall of Queen Himiko is just a wooden longhouse with a grass roof, like those ancient houses in Shirakawa, the basis of the town in Higurashi When They Cry. Himiko is as much a shaman as a queen, but despite her mystical powers she is a frail old woman, and her imminent death threatens the stability of the 29 separate countries which make up early Japan. Himiko's right-hand man, Chosei, is a doctor and military attache from the country of Gi (China). Chosei seems to be merely a faithful advisor, but in fact he has a secret motive: to make Yamatai into a Chinese province. To do this, he hopes to groom 13-year-old Iyo, one of Himiko's sacred virgin priestesses, into the new queen.

Iyo, an innocent girl who spends most of her time training her spiritual powers by standing under waterfalls, has no interest in ruling Yamatai. "I don't know how to rule a country! I still like playing in the fields with the animals and birds!" But Chosei has plans for her, and so does the swordsman Kiji-no-Hiko, Himiko's bodyguard, who has a thing for the beautiful girl. "The queen is on her deathbed! Yamatai can be ours!" he tells her. When Kiji-no-Hiko makes his move on Iyo when she's in the bath, she blasts him with a bolt of energy: all that psychic training isn't for nothing. Kiji-no-Hiko is persistent, and things get tense. And then Iyo is rescued by a strange boy who jumps out of the trees: a boy with a wild head of spiky hair: the "lightning headed boy," Raika.

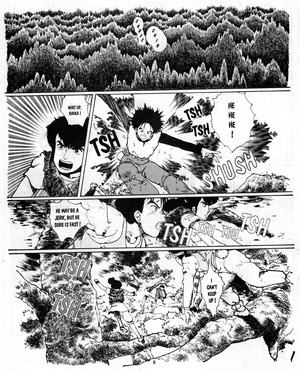

Raika is one of a group of orphan boys who live in a treehouse on Kumaki Mountain, in land unclaimed by the warring clans. To the surprise of Kiji-no-Hiko, they've been trained in shinsenjutsu (translated here as "mountain magic"), an assortment of ninja-like arts. ("Do you expect me to believe that there are kids who can use shinsenjutsu out here in the middle of nowhere?") They travel by leaping from tree to tree, they can throw shuriken in the blink of an eye, and they're generally awesome. They owe their training to Master Roshi (not a reference to Dragon Ball since it's actually a title, not a name), the old man of the woods. Master Roshi, like Chosei, is Chinese, and has come to Japan bringing the superior knowledge of his culture: martial arts originated in China, after all. But Roshi advises his pupils to avoid getting involved in the conflicts of Yamatai and its rivals. "Both countries will be destroyed," he warns them. ""We have no country or empire. We are shackled by no man or thing. How you live and how you die is the most important decision you will make."

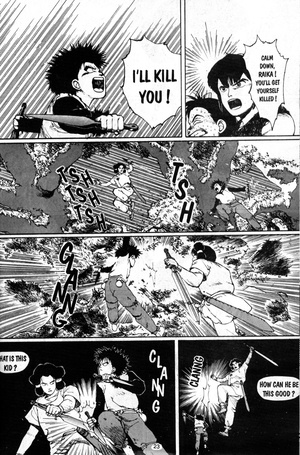

Raika doesn't care about politics, but he has a sense of justice, and he leaves the would-be rapist Kiji-no-Hiko humiliated with a scar on his cheek ("I don't like rape, mister!"). He then returns to the treehouse, but afterwards, he can't help thinking of Iyo and wondering about the world outside the forest. Meanwhile, the discovery of Raika and Master Roshi throws a wild card into Chosei's plans. ("It's the duty of the Ambassador of Gi to manipulate these babies of Yamatai. But if there is another Chinese involved, it changes the equation!") Chosei sends an assassin to kill the wild boys, and Iyo risks her life to send Raika a magatama bead to warn him. As various factions compete for power, open battle soon erupts. Who will win, and will Iyo and Raika survive?

One of the best things about Raika is the setting. 3rd century Japan is rarely depicted in manga, but here it is, a primitive society where priestesses perform divination with turtle shells and important personages are buried along with their sacrificed slaves. (The manga suggests that the latter might have been an imported Chinese custom.) Iyo is a bit of a damsel-in-distress type, but she and Raika are both likeable characters in a rough world. This is no happy shonen or shojo manga where no one gets hurt; people die, people get their arms chopped off, life is harsh. (Although it's also not one of those manga that rubs your face in how brutal things are.) But it's not all grim and gritty. Half the manga takes place on the ground; the other half takes place up in the treetops, where the shinsenjutsu masters jump around and rush at super-speed through the trees.

Fujiwara's detailed art and realistic, if sometimes stiff-looking character designs show the mark of Katsuhiro Otomo; Japanese wikipedia says he's also influenced by one of Otomo's favorites, the real deal himself, the French artist Moebius. If Fujiwara's backgrounds aren't quite as detailed as Otomo's, maybe that's because all he's got to draw in Raika is a bunch of trees and huts rather than motorcycles and skyscrapers. But the most obvious inspiration for Raika are the ninja manga of Sanpei Shirato. Shirato wrote dozens of ninja manga, most notably the 1959-1962 Ninja Bugeicho and the 1964-1971 Kamui Den ("Legend of Kamui"). Even Kamui Fujiwara's pen name, Kamui, is based on Shirato's manga. (Or, possibly, they're both based on the same source word, the Ainu word for god.) Shirato's works are classic manga that will probably never be translated because they're thousands and thousands of pages long. (Viz did translate one of Shirato's works in 1987, as The Legend of Kamui, but despite its nice Lone Wolf and Cub-like artwork and interesting stories it's just a spinoff of the original Kamui Den, drawn by one of Shirato's many uncredited assistants.) In Shirato's works, like in Raika, the ninja are mysterious masters of their craft, outsiders living in the wilderness, beyond the edges of society.

Shirato's longer works are historical fictions about class war and political upheaval—Kamui Den even ran in the underground manga magazine Garo—but Shirato is ultimately most influential for his contributions to ninja mythology. His manga are full of ninja jumping mighty leaps in the air, Legend of Kage style ninja throwing dozens of knives at once, ninja vanishing leaving only a block of wood in their clothes to baffle their opponents, ninja named "Sasuke," etc. These techniques would later appear in a thousand other manga, as the even more exaggerated ninjutsu in Naruto, or the shinsenjutsu in Raika.

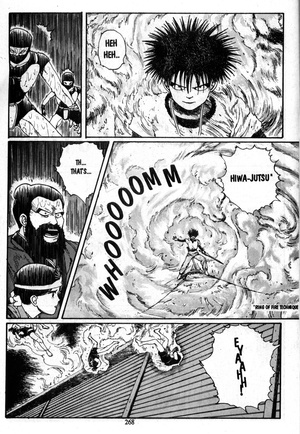

The really interesting thing about Raika is that the shinsenjutsu aren't just variants of ninjutsu; they're more like Early Iron Age ninjutsu. "The mountain magic technique is the forerunner to ninjutsu," one character explains. The heroes' powers in Raika almost seem like something you could learn to do if you were the world's greatest Boy Scout or you took a really great class in homeopathic medicine. This includes things like imitating bird calls, training wolves and owls and other animals, and making smoke bombs and poisons from various natural materials: pollen, plum pits, rudimentary gunpowder. There's also the chi-like power to project electrical energy, the power to hang upside down from the ceiling, and the power to move so fast you really confuse your enemies, but on the whole the powers in Raika seem right in line with the primitive arms and equipment the non-ninjas use. A low-tech setting needs low-tech ninja. In a world full of manga where everyone is leveling up like crazy, and ninja characters are splitting into thousands of doppelgangers and summoning 100-foot-tall giant frogs, it's refreshing to read a manga where the characters are just really skilled human beings.

The English edition of Raika by Sun Comics, which lasted for 20 monthly comic issues from 1992-1993, was an enormous bone-job. It's not that the translation was bad, although the lettering was pretty awful, with no effort to make the art bleed off the pages properly, meaning that you get to see all of the sloppy edges of Fujiwara's drawings. (What's interesting about this, at least if you're an ex-manga-editor, is that it means Sun Comics got access to the original high-quality photographic negatives of Raika's art, something many manga publishers don't even bother to do, instead preferring to just scan the pages directly from the tankobon because it's cheaper. And they STILL screwed it up.) What's sad about Raika isn't the print quality, but the fact that, according to experienced Viz and Del Rey translator Bill Flanagan (for whom Raika was his first professional work), the American publisher 'mysteriously' vanished, taking with him all the profits for the books, leaving thousands of dollars owed to the printers, the Japanese licensors and the other people working for him. It's a shame, because if Raika had been licensed by a more legitimate publisher, it could have been a pretty successful manga in the '90s. As it was, it was still the most successful (and best) of Sun Comics' handful of titles. However, Sun did censor the manga; whenever the female characters appear naked, which isn't often anyway, they don't have nipples.

The Japanese edition of Raika is hard to find, but the English issues are still pretty easy to get on comics websites, if you don't mind collecting an incomplete edition of the story. It's an interesting, fast-paced historical drama with some good fight scenes that might remind you of other ninja manga you've read. Also, it's nice to read a story where the characters live in thatch-roofed huts and have kepatsu hairstyles (except for Raika of course) and still manage to be totally badass. Someday, I want to be like Iyo and train a dog to throw a shuriken with its mouth.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (15 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history