Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - The Drifting Classroom

by Jason Thompson,

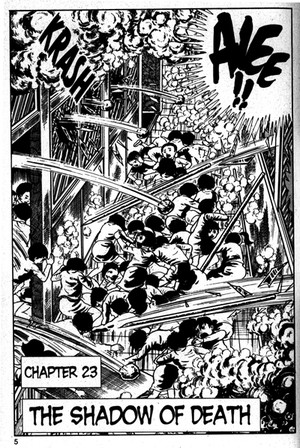

Episode XIX: The Drifting Classroom

"When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child."-1 Corinthians 13:11

The one word that describes Kazuo Umezu's manga is childlike. This is a compliment, not an insult. Kazuo Umezu, a mangaka born in 1936 whose career boomed from the '60s through the '80s, spent his lifetime crafting strange fantasies for and about children, stories of goofy comedy and terrible fear.

Umezu was born in 1934, and in the true Bakuman. spirit, drew manga pretty much continuously from the 1950s until he retired in 1995. His earliest works were shojo manga, dainty stories of delicate girls from a time when men still drew the majority of girls' comics. He later branched into shonen monster, horror and science fiction manga, drawing a manga adaptation of the tokusatsu series Ultraman, and numerous other creepy stories. His most famous manga, in Japan, is the kiddie gag manga Makoto-chan, which combines slapstick, poop jokes and weird hand gestures. But by the 1970s and 1980s Umezu turned hard to horror, and his longest-running works—My Name Is Shingo, Fourteen, The Left Hand of God, The Right Hand of the Devil—are all horror manga which capture the fever-dream sensation of being a helpless child in a nightmarish world.

Umezu himself is sort of a fever dream. Like Hirohiko Araki (creator of "WRRYYYYYYY!!!"), he's one of the few mangaka who is probably more popular in America from internet memes than from his actual work. After he stopped drawing manga full-time in 1995, Umezu didn't just get married and have kids, or sit at home reading porn, like all too many other mangaka; instead, he indulged in his theatrical side to the extreme. He spent more time traveling overseas (according to a friend, he has a house in San Francisco, where one of his one-shot manga is set). He devoted more time to singing in his band, a hobby of his since the 1970s. He appeared on Japanese talk shows and sang a rousing cover of Paul Anka's "You Are My Destiny." In early 2010, he attended a dinner show in Odaiba celebrating his 55th anniversary as a manga artist, in which he appeared wearing his trademark red-and-white striped shirt as well as a flower in his hair and a feather boa. In 2007, he built a new house in Musashino, Tokyo and painted the outside in red and white stripes, prompting a lawsuit from his neighbors to preserve the character of the neighborhood. (Luckily, Umezu won.) Like some wizened sadhu of manga, a performance artist, a confirmed bachelor of the manga lifestyle, Umezu seems to be living the life of a man with no regrets. Whatever popularity he has lost as a mainstream manga artist has been replaced with ten times his weight in cult/underground popularity. He actually seems to have become more popular after his retirement.

Luckily, his manga is great too. Umezu's best manga available in English is The Drifting Classroom, one of the most powerful postapocalyptic horror manga ever made. (Disclaimer: I edited the Viz edition of The Drifting Classroom.) The plot of The Drifting Classroom is an elementary school student's daydream: what if the outside world went away, and the teachers went away, and all that was left was the school? Who would panic, who would stay calm? Where would you find food and water? Who would kill who, who would fall in love with who? Would it be a blessing to be free from the day-to-day routine, or would you all die slowly and painfully?

After a fateful argument with his mother ("You're not my mom as far as I'm concerned! I'm never Coming Home!"), elementary school student Sho arrives at school just in time for the entire school to be shaken by what appears at first to be an earthquake. When the teachers go outside to see what the screaming is about, they are struck by an awful sight: all the buildings and landscape features around the school have disappeared, and the school stands alone in what seems to be an endless wasteland of black clouds and gray, ashy mud. Meanwhile, back in the real world, Sho's mother and the other neighborhood parents hear an explosion, and rush to the school to find that nothing is left of it but a giant pit in the ground. The school has drifted away, teleported to another place and time.

The manga explores the reactions of the students and teachers to this unbelievable situation. At first, the school's dumbfounded teachers think that the outside world has been annihilated in a nuclear holocaust, a diagnosis supported by the fact that the first student to go out into the wasteland falls down dead. ("R-really…those kids would be better off dead! I mean, there may not be a single living person left in Tokyo…no…in all of Japan! We must be in an air bubble…the air outside the school is full of radiation…the whole world could be contaminated with poison, and there's nothing we can do!") The students panic. The teachers slap them into shape and then lie to them to calm them down, saying that the situation is all under control. But beneath their veneer of competence, the adults are breaking down, and soon they all die or go insane, except for Sekiya the cafeteria worker, a selfish swine who terrorizes the children and hoards all the food for himself. Sekiya maintains his sanity by being completely in denial, sure that the American military will come and rescue him if he lives long enough. (Political content ahoy!) Only the children are able to face the reality in front of them.

And the reality is bad. Sho and his friends soon realize that their school has been transported in time to the far future, a future in which the world as we know it has been utterly destroyed. Everything is dead; all that is left are buried skyscrapers, dried riverbeds and the buried foundations of buildings. Pollution has destroyed the world; in one early scene the characters find a flower, only to discover that it is plastic, the top of a vast heap of buried trash. The earth is a garbage dump of sludge and poison smog. And slowly at first, then quickly, the kids begin dying.

The Drifting Classroom is both a horror story and a survival story, like Lord of the Flies to the 100th degree. In poorly-written horror stories, the characters have to behave like idiots to fall into the traps/monsters/deaths that await them. But in The Drifting Classroom, the heroes try their hardest and act their smartest and die anyway. Sho, who is the bravest and smartest (except for Gamo the smartypants egghead, and possibly Sho's lady friend Saki), soon becomes the leader of the kids and tries to guide them to work together and save themselves. They plant a vegetable garden. They gather the water from the school swimming pool and drink it. They rig up a human-powered electrical system using bicycles. They try to find a way back home.

But nothing works. The students split into warring bands and fight one another. Little kids start committing suicide by jumping off the roof, calling out pathetically for their mommies as they do. A centipede-like monster crawls out of the desert and tears the students to pieces. Swarms of flesh-eating insects attack. The thirsty students are pleased when rain falls, but not so pleased when the rains cause a massive flood which smashes into the school with such force the water rips people's heads from their shoulders. Fate is cruel. At one point, Sho lies dying of appendicitis, and a Brave group of students risks their lives to bring him anesthetic so they can perform surgery on him. Most of the "anesthetic-finding team" dies on their quest, but while they're away, the other students decide they don't have any time to waste and perform the operation anyway, without anesthetic. That's right, kids: sacrifices can be meaningless!

And of course, what is a disaster story without agonizing moral conundrums? In The Drifting Classroom, not a volume goes by without the heroes having to make some desperate decision. Should they use Sekiya, the evil bastard school janitor, as a lab rat by feeding him mysterious far-future food? When one student contracts the black plague, will anyone tend to him in his illness, or will they let him die alone in pain to keep the plague from spreading? Can they kill a single innocent student to save the lives of all the others? How about a couple of students? Sho continually speaks out for the side of good and idealism. His rival for the leadership, Otomo, is more hard-hearted and cynical ("We have to figure out how to survive on anything, whether it's polluted water, poisonous food, or human flesh!") Sho's goodness at first seems like a heroic cliché, and in fact it really is a bit, but in the last volume we discover that he and his rival have more depth than they first appeared. As the characters are tested, we discover more and more secrets about them and the awful world they now dwell in.

Umezu's dark, muddy, oldschool artwork is part of the story's power. His character poses are stiff, his figures sometimes awkward, his number of character designs (particularly of adults) not so great. He even has the bad perspective of a child's drawings, that isometric-3D Farmville look. But Umezu is a master of pacing and perfectly chosen images. His meaningful way of using every page and panel reminds me of something once said by Lupin III creator Monkey Punch (paraphrased): "In Western comics, the basic division of space is the panel. In Japanese comics, the basic division of space is the page." The paneling in The Drifting Classroom varies from talky tiny-paneled pages of 12 or more panels each, to intense sequences of as many as three two-page spreads in a row. When Sho first sees the devastated future world, there's four pages of nothing but his face looking out over the landscape in increasing closeup. Repetition and size drills in the shock and horror. Volume 1 ends with three full pages of closeups of a child's hand being crushed. Many times reading The Drifting Classroom, we know something awful is going to be around the next page-turn, but we just…can't…stop ourselves from turning the page. Umezu also powerfully switches between super-detailed artwork of backgrounds and monsters, and big, bold images of the characters themselves. The closeup of a face with bulging eyes and a screaming mouth is an Umezu trademark; you can see them parodied in some modern comedy manga.

But although Umezu's work borders on absurd comedy (sometimes just because things are so awful for the characters you have to laugh), it's actually quite scary, because it's sincere. It's as earnest as any Shonen Jump manga, in fact much more earnest now that Shonen Jump has become a self-referential port for shipping fantasies, but it doesn't always have a happy ending. Irony and snark do not have a place in Umezu's world; he clearly believes in the characters' dreams even as he crushes them. Ng Suat Tong, a frequent contributor to The Comics Journal (www.tcj.com), compared Umezu to Henry Darger (1892-1973), one of the world's most famous "outsider artists." Darger, a reclusive janitor with no friends or family, became posthumously famous when it was discovered that he had spent nearly ever spare moment of his life working on a 15,000+ page illustrated book, The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal. A story of war and torment in a country inhabited entirely by innocent-looking little girls, Darger filled page after page with elaborate illustrations of children being killed and killing, being tortured and turning the tables on their torturers. Like Darger's work, The Drifting Classroom is never explicitly sexual (it is shonen manga after all), but the shadow of some kind of dark abuse…something awful…lurks behind the scenes, just like the shadowy giant centipede that lurks in the desert, waiting to terrorize the school.

Umezu didn't end up a starving recluse (he seems more like an exhibitionist), but his work does have something in common with Darger's. For both Darger and Umezu, children and innocence are the ultimate good and adulthood is the ultimate evil. 38-year-old single male Sekiya, a character close to Umezu's age at the time when he wrote it, is a total scumbag. The only decent adults are mothers, such as Sho's mother, who seems to share a psychic link with him across time. Several cliffhanger plot points are resolved by Sho's mother sending him "time capsules" of items he needs from the past, for instance burying stuff where she knows Sho will find it. His mother is literally a saint; at one point, Sho's classmates decide that they need a "god" to worship to increase morale, and so they pray to a plaster bust of Sho's mother that he made in shop class. ("She represents all the things we care about! She gives us hope that we'll return to our world!") In his typical irony-free way, Umezu seems to stand in awe of Sho's mother even as she becomes increasingly unhinged and fanatical in her conviction that her son is alive. The affection of a mother for her child, apparently, overcomes time, space and conventional morality. On the other hand, the elementary-school-age girls aren't nearly as glamorized, except for Saki's pure heart; the girls are distinctly a separate lot from the boys, and Umezu makes one or two casually sexist 1972-era remarks about them being just a bunch of silly girls who can't be good leaders because they've got ovaries. But crazy statements are a part of every Kazuo Umezu manga. His understanding of ecology and composting isn't that great either.

With psychic powers, time travel, monsters and even a baseball scene, The Drifting Classroom is an unforgettable manga, a story with tons of plot twists which careens wildly towards everyone's deaths. (Or does it?) It's a story of doing the right thing in a cruel, Darwinistic, dog-eat-dog world. Its scenes of monsters, apocalypse and destruction would be echoed years later in another, even more twisted Kazuo Umezu manga, Fourteen, a far-future end-of-the-world epic which contains such horrible scenes of cruelty to children it would probably be literally illegal to publish in America. I'd love to see someone publish it anyway, or some of his other science fiction and horror manga, but sadly, Umezu's work is the type of manga that's least suited for the English market: fugly-looking and super-super LOOONNNNG, with his best series stretching into the thousands of pages. And then there's the gore; although The Drifting Classroom is really one of Umezu's least offensively violent manga, Viz felt the need to rate it 18+, so its intended target audience of junior high students can't officially read it. But the important thing is, it's out there. And it's harrowing. Read it and laugh, read it and weep.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (20 posts) |