Brain Diving

Double Impact

by Brian Ruh,

All writers have egos that need to be fed. Think of it this way – pretty much anyone can string words and sentences together, but it takes a certain kind of person to say “my particular arrangement of letters is skillful enough that you should pay attention to what I have to say and perhaps (if I'm lucky) even pay me for the privilege.” Sure, a lot of us try to be humble, but we often take what we do pretty seriously.

All writers have egos that need to be fed. Think of it this way – pretty much anyone can string words and sentences together, but it takes a certain kind of person to say “my particular arrangement of letters is skillful enough that you should pay attention to what I have to say and perhaps (if I'm lucky) even pay me for the privilege.” Sure, a lot of us try to be humble, but we often take what we do pretty seriously. Basically, I am building up to a confession: whenever I come across a new book on anime, I always have to check to see if my book on Mamoru Oshii is listed in the bibliography. I'll admit, it's a pretty good feeling to see that someone else has found something that I've written worthwhile enough to respond to, even if it's to argue with something I've said. In a sense, I guess writing is a form of immortality. Regardless of what happens from here on out, traces of ideas I've put out into the world will remain.

So the first thing I did when I picked up a copy of Manga Impact! The World of Japanese Animation was to flip to the end to check out the bibliography. Once satisfied that this book passed my “exacting standards” (i.e. my book was in fact listed in the back), I was curious to see what other books made the cut to be listed as a source. There were a lot of good ones in there, and I recognized nearly all of them. (This may have to do with the relatively small number of books on anime and manga in English than anything else.) However, one publication in particular jumped out at me – a title called Studio Ghibli by Frederic P. Miller, Agnes F. Vandome, and John McBrewster. If you've ever gone browsing for titles on Amazon, these names will probably be familiar to you as the “authors” of thousands of books on a wide variety of subjects. In reality, the books released by these folks are nothing but compilations of information already freely available on Wikipedia.

The inclusion of this Studio Ghibli book instantly made me wonder about the quality of the rest of the publication. I wasn't sure which scenario would be worse – if someone had just seen a listing for the book on Amazon and threw it into the bibliography without checking its contents, or if someone had seriously evaluated the book and decided that it was up to his or her standards. Neither sat particularly well with me, so I began reading Manga Impact with my critical eye already set in a skeptical state.

Manga Impact is the just the latest in a line of books that attempt to give a grand overview of the phenomenon of Japanese comics and animation. As I've said in previous columns, such books were useful back in the day, but I'm growing skeptical of how much good they are providing for readers. I'd like to see time and resources invested into more in-depth examinations of particular directors or genres. (For example, I'd love to see a book on Isao Takahata or one on sports anime & manga.) Particularly since the advent of Wikipedia, anime and manga blogs, etc., there's no shortage of basic info about Japanese popular culture out there. Rather, I think what it's lacking in general is some solid interpretation and analysis to make sense of it all.

In the preface to Manga Impact, the editors try to paint the book's efforts in the best possible light. The overall style of the book's design is made to reflect a stereotypical comic book aesthetic, which is supposed to be “in honor of Japanese animation's ‘big brother.’” This of course brings up the issue of whether the book is actually about comics or animation, which is not immediately clear from the title. So, Manga Impact: The World of Japanese Animation, which one will you really be talking about, manga or anime? In response to the question, the editors begin to wax rhapsodic about their efforts: “Quoted in the title and immediately denied in the subtitle, manga permeates this book. Here and there it surfaces… before submerging once more into the body of that phenomenon – animation – that has at different times plundered manga, denied it, exalted it, or fostered it.” In other words, the book really is about anime, but they'll talk about manga when they need to (neglected here is the relationship between anime, manga and video games, although it is in fact discussed to a small degree throughout).

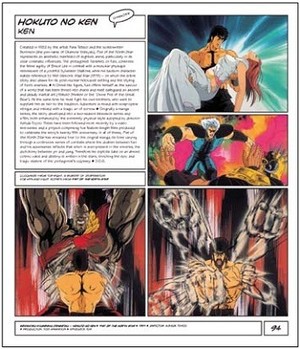

Occupying the majority of the book is a set of illustrated encyclopedia entries – from .hack to Kunihiko Yuyama – that is supposed to be a “fascinating journey” through anime and manga culture. In the interest of presenting “the most democratic structure possible” the editors reject “hierarchies” and list the subjects in alphabetical order. (The alphabet – what a revolutionary concept!) Each subject is given a classification of what type of media it is (film, TV series), what role the person played in the creative process (director, animator, mangaka), if the entry is for a fictional character, and so on. Some entries span more than one category, such as the one for the late Yoshifumi Kondō, who is listed as character designer, scriptwriter, and animator. There are often a handful of images illustrating the entry as well as a short description or explanation of varying quality. (There were multiple contributors to the book who helped to write the entries.) Some of the entries can be rather perplexing. For example, the book categorizes Maison Ikkoku as a fictional place rather than a manga or anime. On top of that, neither of the two images used in the entry actually show the building! And in fact one of them is mislabeled as showing Kyoko and Godai from the series when it really depicts Sakura and Ataru from Urusei Yatsura.

One of the prime points in this book's favor is that it takes on anime and manga from a different viewpoint than we often get in English. Although the genesis of Manga Impact is puzzlingly not noted anywhere in the book, in fact it began as an exhibition of Japanese animation at the 62nd Film Festival Locarno, held in Italy in 2009. This origin explains the preponderance of Italian contributors to the book, which provides a different perspective on Japanese popular culture. Paging through the book, I found a number of entries that I would not have thought to include if I were creating such a list. One such entry was for the character of Willy Fog, protagonist of Around The World With Willy Fog, a mid-1980s Spanish/Japanese co-production that adapted Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days and populated the story with anthropomorphic animals. I must admit that before reading Manga Impact I'd never even heard of this series, although it was apparently very popular in Europe (and is out on DVD in English in the UK). I always like finding little gems like these that I didn't know existed.

One of the prime points in this book's favor is that it takes on anime and manga from a different viewpoint than we often get in English. Although the genesis of Manga Impact is puzzlingly not noted anywhere in the book, in fact it began as an exhibition of Japanese animation at the 62nd Film Festival Locarno, held in Italy in 2009. This origin explains the preponderance of Italian contributors to the book, which provides a different perspective on Japanese popular culture. Paging through the book, I found a number of entries that I would not have thought to include if I were creating such a list. One such entry was for the character of Willy Fog, protagonist of Around The World With Willy Fog, a mid-1980s Spanish/Japanese co-production that adapted Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days and populated the story with anthropomorphic animals. I must admit that before reading Manga Impact I'd never even heard of this series, although it was apparently very popular in Europe (and is out on DVD in English in the UK). I always like finding little gems like these that I didn't know existed.Additionally, the book encompasses aspects of Japanese animation that are frequently overlooked by many fans. For example, there is an entry for famed animator Kihachiro Kawamoto. Even though his medium is unquestionably animation, he works with puppets, paper, and other such materials rather than drawn images. Experimental animator Yōji Kuri, who collaborated with Yoko Ono, also makes an appearance, as does ROBOT Communications, a production company that produces a variety of animation for TV commercials and films. ROBOT Communications’ own Kunio Katō won an Oscar in 2009 for the short animated film La Maison en Petits Cubes.

However, Manga Impact really falls flat when it comes to the images it uses. This is quite unfortunate, since these images take up a sizable chunk of the book. First of all, the pages are printed on thin, low quality paper that feels like newsprint, making the colors appear faded and the images rather blurry. I can understand that a reduction is paper quality can help to keep the price down, but I've seen large books that use quality, glossy paper retail for less than Manga Impact’s $40.

The specific images used to illustrate some of the entries are rather odd as well. For example, nearly all of the images used are from anime, even when discussing a manga title or creator. The images chosen also tend not to be what would be thought of as the most representative of a particular entry. For example, for Kyoto Animation, the images used are of scenes from the 2003 OAV Munto, rather than one of their more high-profile titles like Haruhi or Lucky Star. The same goes for the images paired with the entry for Gainax, which is all Gurren Lagann. Some of the images aren't even what they're supposed to be. For example, the entry for Ichirō Itano is supposed to have storyboards from Blassreiter depicting a famed “Itano circus” of swirling missiles. The storyboards may be correctly attributed to the series, but that is certainly no Itano circus I see on the page. In another gaffe, three of the four images for the entry on scriptwriter Kazunori Itō are for Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, a film Ito had no involvement in at all (although he did write the first Ghost in the Shell film). Am I being nitpicky? You bet! Could I go on? Undoubtedly. I think such inattention to detail shows that the book was being assembled by someone who either didn't know or didn't care about getting their facts correct.

I certainly don't want to drag the rest of the contributors into the crossfire. Having contributed to a compendium book like this before, I know how these things often work – you get your assignment, write your pieces, send them to the editor, and then hope for the best when the finished product comes out. If you're lucky you'll get some say in the editing process. But you often have no control over the rest of it. In the end, the responsibility for things like this lies with the editors.

The final pages of the book consist of a series of a series of essays on anime and manga from the various contributors, with each one allotted a mere page. The main problem with these essays is that, much like the rest of the book, the short format really doesn't let the author go into enough detail to make a coherent point, and as with the content in the rest of the book, the quality can vary wildly. Stephane Delorme's essay “Childish Perceptions: Thoughts on the Japanese Genius for Animation,” tries to explain why such good animation has come from Japan, but his treatise could be pretty offensive if read in the wrong light. It reminded me of the infamous time in 1951 Douglas MacArthur compared the Japanese people to twelve-year-old children. Similarly perplexing is Stephen Sarrazin's essay “Ero-anime: Manga Comes Alive,” which begins “In light of how pervasive erotic animation is in contemporary Japan, we can only wonder at the speed and urgency with which it made its way into the core of its pop culture.” I'm just not sure what to make of the rest of his essay if that's what he's going to take as his starting point. I really don't think erotic animation is in any way as mainstream within Japanese society as he is making it out to be. And later in the piece he repeats that old (and oft-disproven) chestnut that in Hayao Miyazaki's Nausicaä the eponymous heroine is shown flying without any panties on. Not all is lost in these essays, though. I quite enjoyed Grazia Paganelli's meditation on time in animation, and Paul Gravett's take on the differences between manga and Western comics is pretty good for its brevity. Equally informative is David Surman's analysis of how video games interrelate with contemporary anime and manga. However, reading through some of these essays, I found myself wishing Helen McCarthy or Jonathan Clements (both of whom contributed to the main “Cast of Characters” portion) had contributed a longer piece to the conclusion.

In the end, Manga Impact is a whirlwind tour of the breadth of anime and manga. The problem is that there is so much to discuss that if you take the same kitchen sink approach this book does, then you'll necessarily need to be pretty shallow in your discussions. Another similar problem is that the encyclopedic approach seems to flatten the importance of each entry, potentially obscuring the really important contributions to the field. Yes, it's definitely a good thing to expand the horizons of what we consider anime and manga and to get a wider knowledge of who has contributed to it. At the same time, though, giving Studio Ghibli and the character Spank from the 1981 series Hello! Spank the same amount of real estate in a book like this downplays the former's importance.

Brian Ruh is the author of Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. You can find him on Twitter at @animeresearch.

discuss this in the forum (15 posts) |