Review

by Rebecca Silverman,Tono Monogatari

GN

| Synopsis: |  |

||

In the early twentieth century, an author by the name of Kunio Yanagita compiled what he claimed were oral legends from the Tono region into a book published as Tono Monogatari, or Tales of Tono. Later manga legend and folklorist Shigeru Mizuki created a manga version of some of the tales collected by Yanagita, retelling them as he wanders through the countryside in a book that is part folktale, part celebration of a time and a place that no longer really exists. |

|||

| Review: | |||

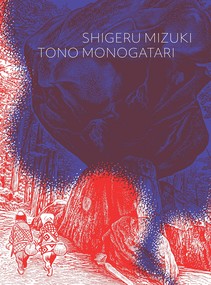

While Shigeru Mizuki was many things and created a wide variety of works, both fiction and nonfiction, what he is largely remembered for is his series Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro, which was most recently adapted into anime form between 2018 and 2020. In that work, Mizuki drew on the folklore of Japan, with an emphasis on the yokai and other similar creatures, sometimes focusing on how they interact with the human world. Some, if not most, of this can be traced back to his relationship with an old woman he called NonNonBâ, who was a grandmother figure to him, and his work that bears her name (which is available in English from Drawn & Quarterly and absolutely recommended reading) serves, in some ways, as a spiritual prequel to this. Although Mizuki was not the original collector of the tales presented in Tono Monogatari (Tales of Tono), his personal history with these stories make his adaptation feel much more personal than many a collection of regional folktales as he offers us a window into a world long gone. The original work was published in 1910 and authored by Kunio Yanagita. Yanagita was interested in preserving what he saw as the heart of Japanese culture, its folklore and religious beliefs, in much the same way as how Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm sought to preserve the cultural heritage of the German oral storytelling tradition. (Yanagita's numbered tales are similar to how the Grimms numbered their stories in their collection; it should be noted that neither of these books' numbers are part of the Aarne-Thompson-Uther [ATU] system of folktale categorization.) But just as financial considerations eventually led to the dressing up (or down) of certain traditional elements in the Grimms' collection, Yanagita also played a bit fast and loose with some of the supposed folkloric aspects of his book. Translator Zack Davisson notes that while Yanagita claimed to have recorded the tales exactly as told to him by Tono native Kizen Sasaki, he in fact prettied them up, although the final copy was told in the first person. It is this narrative style that allows Mizuki to enter into the retelling of the work in such depth. Readers of Mizuki's work know that, even when the books aren't autobiographical, he has a habit of inserting himself into the stories. That's precisely what he does in reworking Tono Monogatari – although he's retelling tales from Yanagita's original book, his base storyline is that Shigeru Mizuki is visiting Tono, wandering the area from which the stories originated. In part that's what helps to tie this spiritually to NonNonBâ, but more than that it gives the book a more personal feel. Folktales, after all, are oral in origin, and there are some theories that state that when they were written down by collectors, the stories' evolutions were stopped in their tracks, rendering them stagnant or frozen in time. (Yes, this theory does ignore printed or filmed reimaginings.) By inserting himself into the book, Mizuki brings back that oral element, framing the book less as if he's creating a manga version of Yanagita's work and more as if we're wandering with him, and these are the stories he tells us on our way. The stories themselves, and their brevity, will be more familiar to people in the habit of reading early, academic folklore collections rather than polished compilations of fairy tales, such as later versions of the Grimms' Children's and Household Tales or Andrew Lang's “colored” fairy books. In many cases, the individual stories read more as snippets rather than developed tales, and the vast majority deal with the same few basic themes: the mountain people (yamabito), Mysterious Disappearances, and ill-advised interactions with the spirit world. That all three of these often overlap is part of what makes them interesting, and Davisson has included several short essays explaining some of the academic theories behind a few of the more common bits and pieces found in the book. Perhaps the most interesting, if only because we don't see them very often in other works in English, are the theories about the mountain people, most frequently referred to in the volume as either yama otoko or yama onna (mountain men and mountain women). These are framed as a supernatural race of beings, somewhat analogous to giants, ogres, or trolls in western mythologies, but Davisson mentions theories about them being in reality the survivors of the Emishi, the indigenous people of Tono, or perhaps survivors of a European shipwreck based on physical descriptions of them. Both are intriguing ideas and certainly in line with prejudices of people being stolen from their homes as we see in many colonial stories of danger (to the colonists, obviously); from an academic perspective it offers an insight into how history can be reframed and is, in fact, in the case of the Emishi, written by the victors. Ghost stories also feature in the collection, as well as stories that may be more familiar to western readers as variants of well-known fairy tales. Of the latter, one particularly interesting story is the one which opens chapter six, about a family's guardian deity incarnating in order to help them out with their fields, something they only discover when they find the statue covered in mud with footprints leading up to it. This has elements of fairy tales about helpers, but also popular horror stories, which may be an indication of how different cultures see various literary elements. Later, in chapter eight, there's a tale about how a generous gift is abused (a bit like “The Fisherman's Wife”) and ends up turning on its owners. The art is beautiful, and as always makes use of Mizuki's trademark style of cartoony people on photorealistic backgrounds. The details of the countryside, primarily forests and mountains, is especially gorgeous this time, and Mizuki draws himself slightly more realistically than usual, which again helps to give us the feel that we're right there with him in his explorations. The translation works with this as well, almost mimicking the patterns used by really good oral storytellers. And, of course, as an added bonus there's a cameo by Nezumi Otoko towards the back of the book. Tono Monogatari is, in Shigeru Mizuki's hand, a journey all by itself. It helps to capture the legends of a place many of us in the English-speaking world may not be aware of, and it makes those stories feel relevant and important, not just in the realm of world folklore, but in terms of just experiencing a story. Certainly you should pick this up if you're a fan of Shigeru Mizuki, but if you just want to read some fairy tales, this is also a good place to find them. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : A

Story : A

Art : A

+ Mimics the experience of listening to a story well, beautiful art, especially the forests. |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (4 posts) | | |||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about |

||