Review

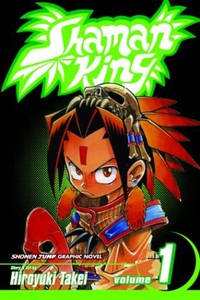

by Justin Freeman,Shaman King

G.novel 1

| Synopsis: |  |

||

Yoh Asakura is an easy-going thirteen-year-old kid who just moved to Tokyo by himself to study. What most people don't know is that Yoh isn't studying for school so much as he's studying to become the world's strongest Shaman. In order to accomplish his task, he must take on and befriend as many lost spirits as possible, learning to use their powers as his own. Along the way he meets Manta Oyamada, a hyper class mate that learns of Yoh's powers while taking a shortcut home through the local cemetery. With Manta at his side (and narrating his tale), Yoh's adventure can truly begin. |

|||

| Review: | |||

Late in the opening volume of Shaman King, our erstwhile hero Yoh Asakura finds time to make a point while fighting his first serious rival. “Ghosts are people too!” he essentially laments, enraged by the notion put forth by the angsty, meglomaniacal Ren that they are mere tools to be wielded by a skillful Shaman. It's a nice point. Typical for a shounen hero, but nice nonetheless. It's a shame manga-ka Hiroyuki Takei doesn't seem to feel the way his protagonist does. These ghosts that everyone is getting in a huff about are more or less the focal point of the entire series. They are what drives everything forward. Good, bad, neutral—all shapes and sizes. The great thing about a ghost that lives inside a boy is that it does not have to be grounded in the reality of the environment. Yoh lives in modern day Tokyo, but at any time he, and thus the reader, can have access to any number of ghosts from any number of places, time periods or backgrounds. That's the draw of Shaman King's premise, really. It promises some exploitation of its creator's imagination. Unfortunately, we don't really get any of that. The only inherent advantage of the ghosts' corporeal existance that the series uses is their ability to be conjured from the ether at will. When Yoh uses, meets, or fights a ghost, that ghost does not need a real reason to exist. It does not need roots of any sort within the story or the environment. As a result, the ghosts end up more like Pokémon or cards than the people Yoh so fervently insists they are. They exist as a gimmick—as collectibles. Largely mundane and one-dimensional, we get to watch as their malleability turns from an exercise in creativity to the ultimate writers' crutch. Hey, need a plot device? How about a deus ex machina? What better than a being that can appear and disappear from the void on a whim? Need a sword? Here's your smithy! You can imagine how this might grow a little tiresome. The ghosts are not the biggest issue, however. It's Takei's misguided focus on them that places the series on the wrong path in the first place. The series is structured in a mostly rigid episodic formula, subscribing to the common manga practice wherein every character trait or relationship quirk is revealed through the course of a mini story. It's the “villain of the week” idea, basically. Manta learns of the power of a Shaman through a run in with a punk at a cemetery. Yoh's commitment to his craft is revealed by confronting a malicious ghost bound to its place of death through emotion. And so on. Some of these stories are interesting in and of themselves, but there is very little binding them together to form a cohesive whole because the characters and narrative they are supposed to enhance really don't have any legs at this point. The only piece of information we know about Yoh at all is that he likes nature. And, hey, go figure, that's kind of what a Shaman is all about. We don't know what he's doing or why he's doing it, and we're not really given a reason to care. Before we can figure out anything about Yoh, Takei unveils a “rival” Shaman, and the magical idea of the “Shaman King”, almost as a substitute for this developmental core. The story takes off before anything has happened, and we are distracted by a barrage of side tales and one-trick ghosts in an effort to build on something that isn't there. Then to top it off, we're told the story through Manta, whose sole purpose seems to be to explain things to the reader in place of Takei letting them develop. He panders to the audience. These are all faults Takei should have been able to avoid, working as he did under Rurouni Kenshin creator Nobuhiro Watsuki for a number of years. With Kenshin, Watsuki established himself as something of a master of this type of storytelling, constantly finding a way to weave the personalities and intentions of his characters into their actions. When Kenshin took action, the reader always knew why. His personality and history were easily reflected in the main arcs of the manga to magnificent effect. The downtime in Kenshin's action—the scenes and chapters that take place between the battles or the arcs--went a long way to establish an emotional base with the cast that is simply not present in Shaman King. Perhaps the most important thing Takei could have learned from Watsuki was that you have to have something to say before you can say it. Takei, however, writes as if he is always looking forward to what is coming next. He wants to write about ghosts, not people! In the world of Shaman King, Yoh is a vessel for his ephemeral allies, but in reality they up end being a vessel for him, to the benefit of no one. If Takei had taken his protagonist's advice and treated ghosts and people as one and the same, things might have turned out differently. Though perhaps, in a way, he did. The ghosts in Shaman King may not behave like people, but then again, neither do the people in Shaman King. I guess Ren wins in the end. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall : D+

Story : D

Art : C

+ A few individual stories have merit |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (11 posts) | | |||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about Release information about |

||