Review

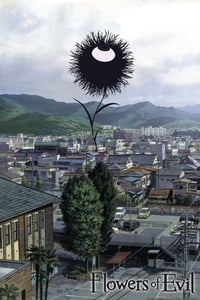

by Carl Kimlinger,Flowers of Evil

Episodes 1-13 Streaming

| Synopsis: |  |

||

Buried in books and generally unnoticed by his classmates, Takao Kasuga is drifting through middle school the way many a dark-minded nerd does: low profile, with maximum disdain for “normal” students. His one guilty pleasure is watching the class idol, pretty Nanako Saeki, from afar. His crush gets infinitely guiltier when, almost by happenstance, he steals her gym uniform. It's an act that demolishes his comfortably anomic life, because it brings Sawa Nakamura into it. Nakamura is the class outsider: dead-eyed, foul-mouthed, considered capable of god knows what by her leery classmates. Nakamura knows what Kasuga did, and she uses the knowledge in fiendishly humiliating ways, the better to expose Kasuga to his “true” nature. |

|||

| Review: | |||

How to describe Flowers of Evil? As Shūzō Oshimi's original manga is often advertised, it's a work of beautifully calibrated, sick-making suspense. As the series is also advertised, it is a “corrupt pure-love story” as well. It is a romance that disturbs; a psychological horror-show that whispers the siren-song of true love. It is a work of piercing insight, staggering stylistic bravery, skillful narrative manipulation, and superbly nuanced characterization—all turned towards endlessly upsetting, disturbingly seductive ends. It is a series that can be attacked from any direction and not crack. It is, in its delightfully unpleasant way, a masterpiece. As it begins, Evil is more sinister psychological thriller than romance: A quiet, punishing thriller that walks its hero through an increasingly murky emotional underworld, each step debasing him further, drawing him away from the light and into Nakamura's sadistic shadow. It's teen life as black-hearted noir, with Kasuga as hapless noir everyman and Nakamura as corrupting femme fatale. The tension of these episodes—the brutal, icy-sweating tension—comes from Nakamura's vicious, capricious sway over Kasuga. She's an unknowable black hole of twisted passions and incomprehensible urges, her whims impossible to predict in all but one way: they are invariably cruel and degrading. Kasuga's slow-motion descent into her orbit, clawing his way toward freedom only to be forced by circumstance to return and sink ever deeper, is queasily fascinating—an exercise in train-wreck rubbernecking with a boy's soul held in balance—but it's when he stops clawing that the show tips over the edge into pure, diseased genius. There is a specific scene in which it happens; a brilliant, mad scene; an outpouring of rage and destruction and misdirected sexual energy of breathless beauty. It would be a capital crime to give away more, but it is there that you clearly see the malevolent tendril sprouting at the heart of Evil's first-love romance, curdling it into something unhealthy, amoral, and yet darkly alluring. It is there that Nakamura becomes a serious love interest. On the surface of it, that flies in the face of logic. But like so many things in Evil, so many disquieting things, the closer you examine it, the more sense it starts to make. No matter how terrifying she is, and she's as terrifying an antagonist as you're likely to find, the series never loses sight of Nakamura's humanity. She's a nasty, knotty, cruel girl. Confounding, willful, and possibly insane. But still a girl. She can be playful and, though she buries it beneath scorching invective and sadistic bullying, she can be hurt. And despite himself Kasuga is drawn to her. The attraction is part sexual, part Stockholm syndrome, and part honest need for her poisonous companionship. It's a ruinously romantic attraction, one that asks Kasuga to sacrifice everything—his dignity, his morality, his freedom—if he's to surrender to it. It's a relationship too deliciously depraved not to root for; too deeply, gloriously wrong not to savor. And savor the series does, as Kasuga's feelings subtly transform and his shifting relationships—with both Saeki and Nakamura—force a searingly honest reckoning with his true nature; as his association with Nakamura darkens the stains on his soul and shatters wholesome Saeki; as Saeki's devastation draws out a troublingly unhealthful attachment; as Kasuga must decide whether to turn from the path Nakamura has dragged him onto or whether to walk hand-in-hand with her into a sweet hell of masochistic pain and immoral freedom. Corrupt pure love indeed. Like any masterwork—that is, any cinematic masterwork—Evil is the product of an improbable confluence: the escalating tensions and twisted romanticism of Oshimi's tale meeting the carefully controlled direction of Hiroshi Nagahama, all during an unlikely flowering of fearless experimentation. It's hard, in the play-it-safe world of modern anime, to imagine how Nagahama and his team got a rotoscoped teen romance greenlit, but they did. Rotoscoping, for those who don't know, is a technique in which live footage is traced over to create animation. The effect, as Nagahama uses it, is astonishing. It's difficult to do justice to it, especially those crucial moments when the effect is new, as the first characters hover into view, the blank, unnaturally mobile outlines of their faces coalescing into distinct features as they trudge with eerie realism towards the camera. It's startling, strange, even upsetting. The series stakes out a no-man's land between the living and animated worlds that is both wonderfully, alarmingly realistic and yet still spookily unreal. It's a style that fits into no easy, prefab anime mold, and quite purposefully so. It fits Oshimi's tale to perfection though. The rotoscoped actors, with their awkward bodies and real-life mannerisms, don't allow for easy distancing; they strip away all the baggage associated with anime character types and their visual tropes and leave us only with these kids and their raw, ugly pubescent feelings. Even the actors' mistakes—and they do make mistakes—somehow add veracity rather than remove it. In the meantime their weird hybrid status, along with Nagahama's beautifully composed settings, contribute to an artistic design that is gorgeous but also a little alien, a little off: perfect for the tainted, disaffected recollections of youth. Nagahama makes the most of his new anti-anime aesthetic. He lets Oshimi's story unfold in sometimes agonizingly long takes, his camera lingering as characters sit and think, walk and feel—a luxury only afforded by the exquisite sensitivity of his animation. His episodes unfold like dark indie shorts, full of suggested emotions and subtly complex relations; artful and reserved, driven by the sinister thrum of Hideyuki Fukasawa's atonal soundtrack and an awful, mounting pressure that forever hints at the psychological horrors lurking around the blind turns in Oshimi's plot. Horrors that inevitably blossom as the evil, fragmented ending theme seeps into the final moments of each episode. Nagahama's ability to choose the right flourish for the right scene—sweetly extended takes as Kasuga and Nakamura walk home in shell-shocked silence; jaw-dropping directorial showboating during a crucial rampage; unsettling lyricism during a life-changing nightmare—is not to be underestimated, but it's his iron control of mood and pace, his mastery of suspense and release, his pitch-perfect handling of unfolding feelings that elevates him, at least here, to the very top ranks of anime directors. It's somewhere around here that someone would normally say something about Evil rekindling our faith in anime or reinvigorating our love of the medium. But that would be a lie. While delighting in Saeki's unexpected sharpness or Kasuga's flagellating self-understanding, we don't feel better about anime characters; we wonder why they all can't surprise and perturb the way Nakamura and company do. When Evil uses our thirst for sick romance to betray our ethics, we don't love anime more; we lament that we don't feel this marvelously, queasily conflicted more often. The problem is that Evil is so good that it makes everything look bad. Which is entirely appropriate. After all, if it left you feeling good, it'd just feel wrong. |

| Grade: | |||

|

Overall (sub) : A+

Story : A

Animation : A+

Art : A+

Music : A

+ A stone-cold masterpiece of psychological sadism and diseased romance; stunningly unconventional visuals and mature direction from an increasingly important director. |

|||

| discuss this in the forum (323 posts) | | |||

| Production Info: | ||

|

Full encyclopedia details about |

||