Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Red-Colored Elegy

by Jason Thompson,

Episode CXXVI: Red Colored Elegy

This is a manga that inspired a love song, a 1972 single of the same name by folk musician Morio Agata. This manga is a love song, a story drawn in visual poetry, a style like almost no other manga I've ever read. If you read enough manga you start to see how different styles are related to one another, but Red Colored Elegy is like a platypus, an evolution of manga that makes you wonder whether it's really real or just something stitched together out of pieces of other animals. But what makes it jump out from so many other 'alternative' comics that are purely formalist and have no emotional connection to the reader is that this is one of the saddest, greatest love stories I've ever read.

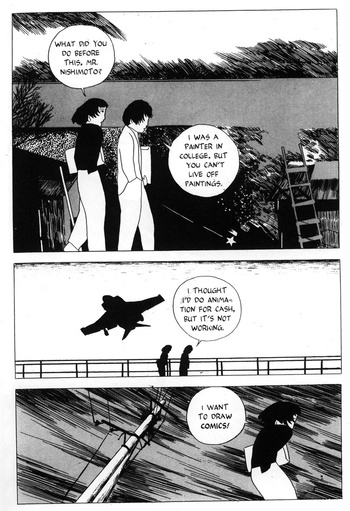

Ichiro is a 20-year-old animator in Tokyo. Delicate-looking, with long hair and poor posture, he spends his days and nights crouched over his table in his tiny apartment, inbetweening cel animation for a few yen (perhaps his company's an overseas contractor for a foreign studio, since there are glimpses of what looks like Disney characters). He dreams of becoming a manga artist. One of his friends is another animator, a girl his age named Sachiko. Sachiko's parents want to pressure her into an arranged marriage. One day she tells Ichiro about it. He asks her why it's any of his business. "It involves you, too," she says.

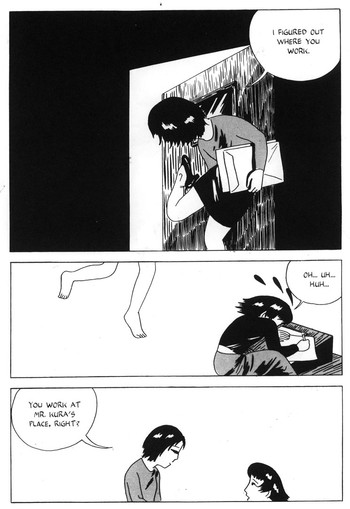

This is her confession of love. Soon, she leaves her family and moves into his apartment. They dance drunkenly and smoke cigarettes and sing pop songs late at night. They kiss and hug and roll on his futon. She poses for his pictures ("What if you becomes a famous artist? I'll be known as your eternal muse.") But they're both desperately poor: they don't make much money, and when it's cold, Sachiko has to warm her hands over a tiny electric burner plugged into the wall. Eventually their enthusiasm must waver: the future is uncertain. Ichiro's manga is rejected by Garo magazine. Animation work is boring and hard to come by. They fight about money. "I'm frightened. Hold me," she tells him. They huddle together for comfort under the light of his hanging lamp, surrounded by darkness, the two of them against the world.

A single graphic novel of 236 pages, Red Colored Elegy was a hit that established Seiichi Hayashi as a major artist, in a time when 'underground' manga had greater cultural impact than they do today. In addition to the love song, it was adapted into a stage play. Its depiction of an unmarried young couple living together, a big deal at the time, was probably one reason for its success; 1972 was also the year that Kazuo Kamimura drew Dôsei Jidai ("The Age of Cohabitation"), a mainstream seinen manga about the trendy topic, complete with the sex scenes that Hayashi leaves (mostly) offscreen. Red Colored Elegy isn'tl a message manga, though. There are no politics here, except perhaps for the silhouette of an American jet fighter that flies above the characters on one of their outdoor walks. Nor, despite how the main characters are always scribbling something, is it a tell-all about the manga industry in the 1960s, like Jiro Taniguchi's A Zoo in Winter or Yoshihiro Tatsumi's A Drifting Life. (Or like so many American indy autobio comics-about-comic-artists.) Red Colored Elegy is all about two lovers and their emotions: from the exhilaration of first love to the missteps and mistakes, the doubt, the drifting apart.

What might be a cheesy love song in another medium becomes beautiful and compelling thanks to Hayashi's storytelling. Fair warning (or challenge) before you start—this is the only manga I've ever read where I got several pages in, then backtracked because I wasn't sure I was reading it from the right side. (The Drawn & Quarterly edition adds a little to the confusion by reprinting it partially flipped and partially unflipped, i.e. rearranging the panels so that the story reads left to right, although within the panels all the art is unflopped.) in contrast to an artist like Yoshihiro Tatsumi, whose gekiga are well-storyboarded but have a grimly repetitive, mechanical feel (Here's 90% of translated Tatsumi stories: look, it's ANOTHER tale of a depressed, sexually frustrated loner in the big city!), Hayashi has wild narrative leaps to match his story's wild emotional leaps. The closest translated comparisons to Hayashi are other underground Garo artists, like Oji Suzuki (A Single Match), but Suzuki's melancholy mood and dark, cryptic drawings are just 10% of the brilliant pallete of Hayashi.

Comic-wise, Red Colored Elegy has more experimentation with technique than 100 other manga. As you read on, it makes more and more sense, and things that first seem like dissociated impressions turn into characters and scenes. Images flow into one another. What is the meaning of the old man juxtaposed with the lizard and the flower? Why is Ichiro drawing a house on fire? What is the meaning of the panel with the bicycle and the star? This manga is full of what Scott McCloud would call "non sequitur" panel transitions—or at least they seem non sequitur at first. Sometimes, the meaning is clearer: when Ichiro and Sachiko realize they love one another, they're drawn as Snow White and the Prince from the Disney movie (animators in love!). The emotional state changes the art; when the characters are happy, everything is bright and cartoony, but when things get dark, we start to see ominous silhouettes instead of faces, and dark lonesome streets. (Hayashi used to work doing experimental shadow/silhouette animation.) And things do get dark. "Don't you have any work? You just lie around all day," Sachiko asks Ichiro. "Stop acting like you're my wife!" he snaps back. A glass falls and shatters. When his father dies, Ichiro goes back to his hometown to be with his mother and sister, and leaves Sachiko in Tokyo, waiting for him in that little white room. Ichiro pours his passion into his work, thinking "Draw—just draw!"

Perhaps because of his own animation training, Hayashi has a great sense of body language. He's a visual storyteller, and shuns dialogue when a pose or an image does the trick: Sachiko twisting around to check her high-heeled shoes, or playing in the surf; Ichiro's slouch; or the curled-up-in-a-ball posture of someone surrendering to despair. At times his character drawings are as simple as James Thurber's, but other times he draws photorealistic closeups of eyes and faces (and yet, often without noses), or perfect little animation sequences like a page of a hand lighting a match. Hayashi worked at Toei Animation in the early '60s, along with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. If Red Colored Elegy were autobiographical, it would have taken place in 1965. Comic artist Eddie Campbellfinds similarities between Red Colored Elegy and films of the '60s and '70s; it was a time when people appreciated more experimental work. But beneath its experimental art techniques, it's a very simple story at heart.

Hayashi is still alive, still professionally making art. His gallery on his website is full of artwork, from delicate children's book illustrations, to portraits of beautiful, slender women in a kind of André E. Marty decadent European style. In 2007, he adapted Red Colored Elegy into a 30 minute animation, digitally animating the whole thing; the film was produced by Toei, but since he's listed as director, screenwriter and animator, it's almost a one-person animation, like Nina Paley. (If you're looking for more info, it's easier to google it under the original Japanese title, Sekishoku Elegy.) The film shows Hayashi's change in style since the manga came out, and maybe a change in his perspective too: Sachiko is more consistently beautiful, more like a lovely statue than the often goofy young woman in the graphic novel. The film has a frame story in which an elderly (animated) Hayashi wanders the streets and thinks of the past.

I once compared Red Colored Elegy to Craig Thompson's Blankets, but actually they don't have much in common except that they're both about the passion of first love (and sex). Thompson's work is baroque in comparison, with its elaborately detailed sequences depicting Bible scenes, the love interest's slender hips under a nightshirt, erotic passages from the Song of Songs. It also has a first-person narrator to make the story clear. Hayashi's work is less visually polished, but it sends out sparks in all directions, unpredictably, like the swaying lamp in Ichiro's apartment. It's got light and shadow, two people in love, four walls, a futon, a drawing desk. That's all Hayashi needs. That's all that many of us need, at least for a little while.

discuss this in the forum (5 posts) |