Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Raijin Comics

by Jason Thompson,

Episode XC: Raijin Comics

Since Viz's Shonen Jump just ceased print publication after 9 years, turning into an online magazine, it seems like a good time to talk about the magazine that started it all. I'm talking of course about Raijin, the magazine more responsible than any other for bringing Weekly Shonen Jump manga to America.

To put it bluntly, they were rivals. Raijin—or rather, its Japanese parent company Coamix—was founded by former Shonen Jump staff: a former editor, Nobuhiko Horie, and two mangaka who worked under him, Tsukasa Hōjō and Tetsuo Hara. All three of them had been manga superstars in the 1980s, producing hits like City Hunter and Fist of the North Star. As times passed, they either (1) decided they could do a better job publishing and editing their stuff than Shueisha could or (2) felt that their declining popularity was Shonen Jump's fault, and so they left and formed a new company, Coamix. In 2001 Coamix formed their own manga magazine, Weekly Comics Bunch, whose flagship titles were Fist of the Blue Sky and Angel Heart (a City Hunter spin-off). Around this time, manga was booming in America, and in 2002, Coamix formed an American branch, Gutsoon! Entertainment, and announced Raijin Comics, essentially an American version of Comics Bunch. And although this was never written in a press release, I suspect that if it wasn't for the desire to crotch-punch their ex-coworkers and prove to them that Jump is awesomer and YOU can't escape us even if you go to America, Shueisha might never have purchased a 50% stake in Viz and launched the American version of Shonen Jump that same year.

I was the launch editor of Viz's Shonen Jump. The announcement of the two magazines was nearly simultaneous, but the behind-the-scene preparations had been going on for months. At 2002, both publishers had huge floor displays at Anime Expo and San Diego Comic-Con, and last that year, the magazines themselves came out. The fierce rivalry between Raijin and Jump can be seen by this email that I received that summer from Sam Humphries, one of the editors of Raijin:

Actually, like in any good shonen manga, the delightful Sam Humphries and I became friends after our battle, and he's now working as a comic book writer. I also shook hands once or twice with Jonathan "Jake" Tarbox, Sam's boss and the true Raijin overlord on the American side, who later went on to work for CMX and as a freelance translator. But the overall feeling between Raijin and Shonen Jump at the time was as hostile and competitive as between…well, as between any two big corporations.

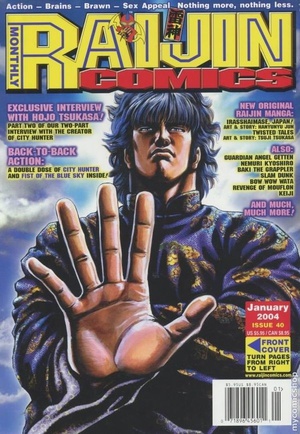

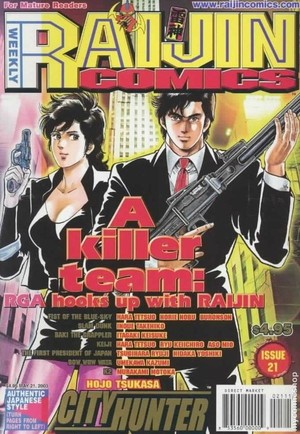

2002 was the year manga hit the big time in America and Raijin was one of the most crazy ambitious projects ever seen launched. Viz, Tokyopop and Dark Horse had already done monthly manga magazines (Manga Vizion, Pulp, Mixx Zine, Super Manga Blast) and Viz had already done weekly manga comics (the first few issues of Area 88 and other early Viz titles were published weekly, until the comics market contracted with the end of the Black & White Comics Boom and Viz basically decided they'd lose less money publishing them monthly), but no one had ever done them together. For those who wanted the "authentic" Japanese experience of getting a manga magazine every week, this was the ultimate, and for fans, that "authenticity" was one of the big factors in Raijin's favor. Like Jump, the magazine was printed right to left, something both Coamix and Shueisha artists could agree on. But in Raijin, names were presented Japanese-style, with the family name first and the personal name second. Also, sound effects were untranslated except for margin notes, in contrast to Viz's Shonen Jump, which intentionally translated the FX in a compromise attempt to appeal to younger readers. And, unlike the early issues of Jump, it had the HYPERACTIVITY of a Japanese magazine. Every page is a graphical overload of fonts and starbursts, and there's dramatic text at the beginning and end of each chapter, basically summarizing what's happening: "A WILD BEAST IS ABOUT TO BE LET LOOSE IN THE UNDERGROUND FIGHTING WORLD!" "THE HIJACKED PLANE IS HEADED STRAIGHT FOR THE DIET BUILDING!" "HOW WILL THE KOREAN CONFLICT AFFECT THE FATE OF JAPAN?" (Shonen Jump later did this as well.) The covers were also dramatic: "FAST-PACED WEEKLY MANGA COMING YOUR WAY!" "MANGA FROM THE MYSTERIOUS EAST!" (…) "MANGA FOR THE REAL FANS!" But even Raijin wasn't "100% authentic"; City Hunter and Fist of the North Star were censored for nudity, sales apparently trumping authenticity concerns in this case.

Still, if you were a subscriber, or you were able to make it to a comic store every week to pick it up, Raijin was your fix for a VERY Japanese-manga-esque experience. (You probably had to find it at a comic store; unlike Shonen Jump, Gutsoon! didn't have the connections to get it widely distributed in bookstores and grocery stores and so on.) The magazine had about 200 pages of manga, plus bonuses such as a video game and anime section (published separately as the pamphlet-sized Fujin), Japanese language lessons starring Cartoon Jonathan Tarbox, and ads for an international manga contest with an $400,000 grand prize. Each of the manga it published deserves its own article, but the Big Three were definitely Fist of the North Star, City Hunter and Takehiko Inoue's basketball manga Slam Dunk, which was the cover feature of the 1st issue. Unlike Hara and Hojo, he managed to get back on good terms with Viz and Shueisha after his fling with Coamix, and as a result Viz has continued to publish his manga and did a license rescue of Slam Dunk. The Raijin edition of Slam Dunk was one of the first sports manga published in the US (but not THE first—that's Yuriko Nishiyama's Harlem Beat, or Rumiko Takahashi's One-Pound Gospel, if boxing counts).

Buronson and Tetsuo Hara's Fist of the North Star had been previously published by Viz, but hadn't been a huge success, although everyone at the company had great affection for it. (When Viz lost the Fist license, a few months before Raijin started, we had a "Goodbye Fist of the North Star" party where we filled a Kenshiro pinata with blood-colored candy and beat it to a pulp while watching the Streamline Pictures dub of the 1985 Fist movie.) The Coamix/Gutsoon! folks chose to release the original Fist as oversize, colored graphic novels—looking a LOT like Chinese martial arts comics—and published the sequel, Fist of the Blue Sky, in Raijin. Set in the 1930s mostly in Shangai, Blue Sky is a prequel to the original postapocalyptic martial arts manga, starring one of the older heirs of the Hokuto Shinken martial arts style. The pulp setting, plus the fact that the main character pretends to be a mild-mannered professor when he's not beating up bad dudes, makes me think it was influenced by Raiders of the Lost Ark. Like the original Fist, Blue Sky isn't exactly a battle manga as I'd define it; the excitement is not so much wondering how the hero will win but watching how he gives various evildoers their just desserts. Hara just LOVES drawing despicable, slimy, cringing bad guys who make you want to see their heads explode. I think there's a Fist of the North Star gene buried in every anime and manga fan's body, and if we were struck by some de-evolving virusor atavistic mind flashback, we'd probably all find that we liked Fist more. (Note: This is not an insult.)

Tsukasa Hōjō's City Hunter will always be stuck in my mind as the manga and anime that introduced me to the term "mokkori." The adventure-comedy story of Ryo Saeba, a hired gun who's got insanely good aim and a love for the ladies, it was incredibly popular in East Asia—check out the insane Jackie Chan film adaptation—but never quite made it big in the States. Like Fist, the art style could be described as Western-looking, but there's something very un-Western about the hero's personality. Like Great Teacher Onizuka (who came much later), he's one of those manga heroes who switches back and forth between being an awesome badass and being a total loser, who saves women from death with his expert gunshots but then, unlike, say, James Bond or Golgo 13, reverts to a childish goof-off lusting after a peek at panties. Incidentally, American manga companies had tried to get the rights to translate City Hunter before Raijin, in the '80s, but Hojo had put his foot down with the demand that his manga had to be published in he original right-to-left format. Another Raijin launch title was Keisuke Itagaki's Baki The Grappler, a martial arts manga so bizarre it's beyond my ability to describe without contorting my body into a pretzel-like shape with a sickening crunching sound. Unlike the others, it had no connection to Shueisha, having been previously published in the ultraviolent shonen magazine Weekly Shōnen Champion. Oddly, it was never released in graphic novel form, unlike the other Raijin manga; who knows why Itagaki didn't give them the graphic novel rights.

These were the four core titles of Raijin, but they also published several shorter manga. One of them, Makoto Niwano's "amoral girl with big boobs killing and torturing people" violence-comedy Bomber Girl, is so awful that I assume it got published because Niwano jumped into an icy river to save Hara and Hojo from drowning. Thankfully, the other short titles were better. Yoichiro Ono and Jiro Ueno's Revenge of Mouflon is the story of Yohei Sano, a 35-year-old Japanese TV personality who becomes a hero and saves everyone when the plane he's on is hijacked by terrorists. Unfortunately for him, while encountering the terrorists he hears incriminating facts about the US government, and the US pressures Japan to arrest him, so Yohei ends up simultaneously fighting his own government, the US government, and terrorists. Revenge of Mouflon is clearly a Japanese response to the 9/11 plane hijackings (with the wishful ending of the plane not crashing), mixing anti-big-government views, political commentary and conspiracy theories with high-volume melodrama and heroic idealism. It's a fascinating mix with good artwork. (Of course, it has a very negative view of the American government, but hey: this is Japanese manga you're reading. JAPANESE manga. Not American manga. So get used to it.) In case you're wondering, it's called "Revenge of Mouflon" because mouflon are wild sheep, in contrast to domesticated sheep who, presumably, would just sit back and take it. ("This is the natural form of sheep before they become domesticated farm animals! Like a mouflon, Sano Yohei is driven by the call of the wild and, little by little, fights back against the enemy!") Ryuji Tsugihara and Yoshiki Hidaka's First President Of Japan is another openly political manga, and it's very interesting in parts, although I find its tale of a badass Japanese politician, who stands up to America, China and North Korea, more comedic than believable. It's sort of like a faltering unintentional prototype for The Legend of Koizumi. Also, it ends very abruptly; I had to check to make sure I really had the last volume. Raijin also published some cool mountaineering manga, and a few chapters of Nemuri Kyoshiro, a manga based on the jidaigeki novels by Renzaburo Shibata.

How could this lineup possibly fail? Well…Raijin lasted 46 issues, switched from a weekly to a monthly format midway through, and collapsed completely in 2004. Christopher Butcher, the manager of possibly North America's greatest comic book store, The Beguiling in Toronto, has written extensively on the failure of Raijin Comics, so I can only add a few points.

First off, Raijin was aimed at a much older and narrower audience than Shonen Jump. Whatever you or I think of it, the popularity of the "rugged" art style of Fist and City Hunter had peaked twenty years earlier; even Coamix's Japanese magazine Weekly Comics Bunch finally folded in 2010, mostly because it never really evolved beyond a nostalgia magazine for people who had been reading those same manga since the '80s. The average age of a Shonen Jump hero is 14; the average age of a Raijin hero is somewhere in their 30s. Or at least they look that way; in contrast to the current popular moe art style, where gender and age differences are minimalized and everyone looks as young and androgynous as possible, Hara and Hojo liked to draw mature, adult women and rugged manly men. (To quote the Wikipedia for Angel Heart: "Xiang-Ying is only 15 years old at the start of the series, despite looking like she was in her early twenties.") Even the name of the company, Gutsoon! Entertainment, is manly. Basically, Raijin was a seinen manga magazine competing in a shonen and shojo world, and their attempt to appeal to older American comic book readers (as opposed to Yu-Gi-Oh! and Pokémon kids) was unsuccessful. Raijin did attempt to make themselves cuter and balance out the overwhelming machismo by publishing some love-comedy manga like Minene Sakurano's Guardian Angel Getten (the fifth core title) and, later, the dog manga Bow Wow Wata, but even these manga looked dated. With these cute manga next to Fist of the Blue Sky, the result was a schizo "What magazine am I reading?" effect, kind of like when Parasyte and Sailor Moon were published side-by-side in Mixx Zine.

Secondly, Shonen Jump simply had much more money and exposure. Virtually every Shonen Jump launch title had an anime spinoff that was on American TV in 2002-2004, not to mention the popularity of the Yu-Gi-Oh! card game and video games. By any factor, it was impossible to imagine Shonen Jump not being more successful. Of course, this can't be directly blamed for Raijin's failure, as the audiences and contents of the magazine were so different; I doubt any manga reader ever came into a comic book store with exactly five bucks in their pocket and couldn't decide whether to spend it on Raijin or Shonen Jump. But the near-simultaneous launch of Shonen Jump certainly sucked a lot of the attention away from Raijin and established Jump as the big manga magazine of 2002 and Raijin as, perhaps, merely its scrappy competitor.

Thirdly, at some level, Raijin was really the pet project of Tetsuo Hara, Tsukasa Hōjō and their editor. It wasn't about publishing "the most successful manga magazine possible", it was about publishing Hara and Hojo's manga. It was obviously daring of them to throw so much money and attention at the American market to launch a weekly magazine, and yet, a clear-eyed analysis of American manga fans in 2002 would have shown that, although manga was on the rise, classic oldschool titles like Fist of the North Star and City Hunter could never be big hits the way they were in Japan in the '80s. Valiantly, stubbornly, they tried to get American fans excited about their manga, but it didn't work. And when it became obvious that Raijin wasn't the success they had hoped it would be, they just tried to appeal to their existing fanbase by adding more Hojo and Hara manga to the lineup (Keiji by Tetsuo Hara and various one-shots by Hojo). Successful manga artists have a lot of clout, and artistic egotism has been responsible for many strange and interesting titles being released in the US (including some Shonen Jump titles), but unfortunately, artists' instincts aren't necessarily more profitable than the commercially guided decisions of big corporations. This is the good and the bad side of the more artist-oriented world of manga, as opposed to the totally corporate-dominated world of companies like Marvel and DC.

And yet, whether it was pure hubris or a really serious attempt to become a force in American publishing, I love Raijin (and other manga magazines) for trying. They really tried to produce something new (in a very old '80s way), and they were part of an exciting time for the manga market. It's unlikely that anyone will ever try to replicate the printed weekly manga magazine experience again, since all the attention has moved online, both in the US and Japan. But on the good side, with digital manga, you don't need to sink millions of dollars into printing and distribution to get your manga out there in public view. Shonen Jump Alpha, from one of the biggest manga publishers in America and Japan, is out there competing in the same format with dojinshi-style publications like ComicLoudand Gen Manga and Yoshitoshi Abe's iTunes dojinshi. Hara and Hojo, you've got fans in the US; if you really want them to read your manga through a legit source, have your assistants translate it and put it on iTunes and Android and Kindle or something. It doesn't have to be any more complicated than that. As I pour a forty in memory of Raijin (and of Weekly Comics Bunch), dreaming of the smell of old cheap newsprint, I hope that someday I'll see the big faces of Kenshiro and Saeba (and Baki) once again floating in the sky, or at least floating online, all '70s shonen manga style.

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (24 posts) |