Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - Jesus

by Jason Thompson,

Episode XXIII: Jesus

"This comic is a work of fiction that draws from historical events and Biblical text. It is intended for entertainment purposes only."

—introduction to Yoshikazu Yasuhiko's Jesus manga

My test for blasphemy is whether something is more blasphemous than Jesus Christ: Vampire Hunter. If it's less blasphemous, I don't care; if it's more blasphemous, I can understand how someone would get offended, although since I'm an atheist, I still really don't care anyway. Since Japan is arguably one of the most secular cultures on Earth, anime and manga provides copious examples of exciting pop-culture sacrilege; even the Japanese language makes it hard to take religion seriously, since the word kami means not just "God" but all kinds of little gods and spirits (and Dragon Ball characters), ten means "Heaven" but is also a part of "tempura," and jigoku means "Hell" but also just a nice steamy hot spring. For every serious treatment of religion in manga, there's one hundred pulpy manga involving demons and devils, the Cabbala (O-Parts Hunter, Neon Genesis Evangelion), Catholicism vs. Protestantism (Pilgrim Jäger), the Gnostic idea that God is evil and humanity has to fight to destroy Him (every single JRPG), or Eastern Orthodox Christianity mixed with breastfeeding fetishism (The Qwaser of Stigmata).

The idea of "god" him/her/itself is sort of religion-neutral, though; what Christians are most often offended by are depictions of Jesus. An image of Jesus on a cross was censored from the Viz edition of Shaman King (in the scene when Yoh is fighting Faust in the graveyard), and crucifixion scenes have been cut out of a lot of translated manga. Despite the artist's joy in creating works like Let's Bible! (in which Jesus comes to earth as a hot girl, making humanity's need to love God all the more visceral), manga publishers generally don't want to cause controversy when push comes to shove, so these instances of censorship, like Comedy Central censoring South Park over Mohammed, almost always happen with the licensors' approval. Hikaru Nakamura's Saint Young Men, a breastfeeding-free comedy manga about the Buddha and Jesus living together as roommates in Tokyo, is one of Japan's bestselling manga, but according to Vertical editor Ed Chavez on twitter, the Japanese licensor doesn't want it to be released in America "until the readership changes here," which seems like shorthand for "until they're sure Americans won't be offended by it." Interestingly, Japan has a small but healthy Christian minority (somewhere in the single-digit percentages), which has produced manga religious tracts like Manga Messiah and the works of Mako Madoka, but I've never heard of an incident in which Japanese Christians protested the representation of their religion in the media. In my extremely scientific survey of one Japanese Christian, she replied essentially "Ahh, who cares, it's just manga." Japan has even had several Christian prime ministers, including infamous mangaphile Taro Aso, suggesting that whatever their opinion of Christianity, Japanese people tend not to get worked up about religion or cast Christians in an us-vs.-them light.

Blasphemous or respectful, to me, the only important factor for a religious manga is whether it's interesting. Specifically, whether it has something new to say, and whether it has actual opinions rather than wishy-washy "well…maaaaybe it's like this…but I don't want to offend anybody" vagueness. By this standard, Yoshikazu Yasuhiko's two-volume manga Jesus is a well-meaning failure. Yasuhiko approaches Jesus' story as history, not religion, making it one of a kind with his other historical biography manga Nijiiro no Trotsky ("Rainbow-colored Trotsky"), Waga namae wa Nero ("My Name Is Nero") and Joan (after Joan of Arc). The lack of supernatural phenomena isn't a problem, but the lack of bold statements about Jesus is, despite Yasuhiko's obvious historical research and his accomplished – and, unusually, full-color – artwork.

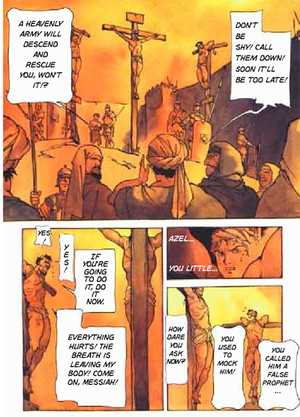

One problem with writing about Jesus is the distance from the subject. Jesus never wrote down his side of the story himself; the New Testament comes from the sometimes conflicting accounts of four of his disciples, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Some Bible readers have even suggested that the four disciples weren't actually talking about the same person. Thus, much guesswork has been made about what the heck Jesus actually did and said (or what he meant by what he said), and any story of Jesus has to resolve contradictions (apparent contradictions, Christians would say). Yasuhiko's solution to this problem is to introduce yet another distancing device, a new disciple, Joshua, a young carpenter, who narrates the story. The manga, then, is the untold Gospel of Joshua. Furthermore, Joshua, who starts out skeptical but becomes a faithful follower after Jesus heals his sister, ends up as one of the two "thieves" crucified alongside Jesus on the hill of Golgotha. It's a powerful framing narrative -- the story begins with our narrator writhing on the cross in the red light of sunset, in terrible pain, waiting for Jesus on the next cross to save him.

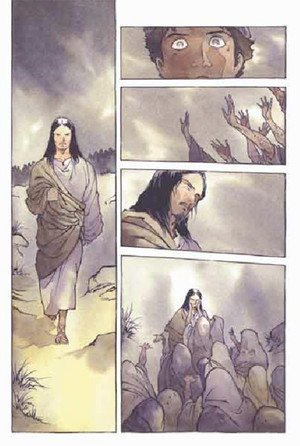

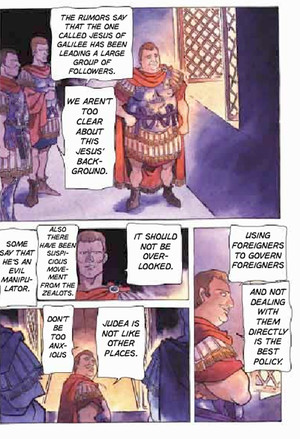

The story then flashes back to the past, as Joshua, who has the fresh-faced look and Greek-god body of all of Yasuhiko's manga protagonists, joins Jesus' disciples and narrates most of the major events of the New Testament. Jesus looks just like the traditional Christian depiction of him. He is a compassionate man and a great orator, who speaks of the Kingdom of Heaven and a forthcoming tribulation (hey, weren't the details of the Tribulation actually mentioned for the first time after Jesus's death, in the Book of Revelation?). Apparently pure in word and deed (Yasuhiko eliminates the few instances where Jesus does something objectionable-seeming, like when he curses the fig tree, or calls a Canaanite woman a dog), Jesus is almost too good for this world. His seeming holiness attracts a ragtag crew of disciples who, in contrast, are full of human flaws such as jealousy and pettiness ("That's the fisherman Peter who always brags that he's the first disciple. What a jerk. I'm closer to Jesus than Peter. I'm a better disciple than he is.") More disturbingly, Jesus also becomes the pawn of other, larger forces. Judas of Iscariot, the "shrewd merchant," is an agent of the Jewish high priest Caiaphas, who wants to find proof that Jesus is a heretic so he can be executed and destroyed. And (in Yasuhiko's biggest historical invention) Barabbas, the Jewish revolutionary, also wants to use Jesus for his own ends, to rouse the Jews into a violent rebellion against the Romans, a Kingdom on Earth rather than a pacifistic, mystical Kingdom of Heaven.

In other words, instead of the traditional Christian interpretation of the Jesus narrative where all the "bad guys" – Judas especially – are really part of God's plan, in Yasuhiko's Jesus, Jesus himself is caught in a spiderweb of grubby human motivations, a pawn of political forces. Or do they just think they're the ones using Jesus, and actually it's the other way around? I guess you could ask that, but on the whole, the manga suggests that Jesus really did sacrifice himself, but he sacrificed himself merely for human ambitions and faith. Mark Simmons, who reviewed Jesus for Manga: The Complete Guide, noted that Yasuhiko "leaves the question of Jesus' divinity seriously open in a way which may offend devout Christians"; I'd match this statement and raise him twenty dollars. In Yasuhiko's version of the story, Barabbas, Judas and the disciples actually contribute to the "cult of Jesus" by falsifying miracles and exaggerating the stories of Jesus' deeds. When Jesus heals Joshua's sister, he does so by staying up all night at her side and tending to her sickness (and lighting a fire to boil hot water in violation of Jewish Sabbath laws), but Barabbas tells Joshua to tell everyone that Jesus cured her with just a touch. In another scene, Barabbas sends someone with money to buy loaves and fishes to give the impression that Jesus is capable of feeding a multitude with a tiny amount of food.

Is Jesus even aware of these shenanigans? Unfortunately, from reading the manga, it's hard to tell. Jesus never takes Joshua into his confidence, so – and this is the main problem of the manga -- we never really know what Jesus is thinking. ("At times his answers sounded painfully vague. He seemed to not know exactly who he was or what he was.") The reason that Nikos Kazantzakis' novel The Last Temptation of Christ, and the 1988 film of the book, were successful and controversial was that they actually went inside the mind of Jesus and gave him human thoughts and motivations, while also accepting that miracles occurred. Yasuhiko does the exact opposite and makes the miracles vague or nonexistent while also leaving Jesus's motivations unclear, leaving us with nothing. Joshua has a bad habit of not being around when Jesus performs some of his miracles, such as healing a blind man ("I had been out on an errand, so I didn't get to see this first hand"). Yasuhiko's Jesus never actually *lies* about anything, but we leave the story with several unanswered questions, such as:

† Does Jesus heal lepers? I still don't know. We see him clutching the hands and heads of the lepers with tremendous compassion, but their bodies don't miraculously regenerate or anything. As he leaves the scene the lepers ask "Are we healed?" as if they, like us, don't know for sure.

† Does Jesus bring Lazarus back from the dead? Maybe. This is one of the few miracles that actually seems to occur, but later on Lazarus says that he was in a "dream," which means he could have been in the afterlife, or merely a coma.

† Was Jesus the son of God? This one is hard to prove without a DNA test, but a skeptical person in the crowd mocks Jesus about his parentage: "They say that he's an illegitimate child! I heard that his mother slept with a Roman soldier!"

† Does Jesus have the power of prophecy? Possibly. He does predict the betrayal of Peter and Judas, but it was pretty obvious at that point.

† Does Jesus have a 'special relationship' with Mary Magdalene? Maybe. While Jesus and Co. are visiting Mary Magdalene, Jesus asks for some time alone with her, and Peter tells Joshua that Magdalene is Jesus' "girlfriend." But Peter is a sleaze, so we can't necessarily trust him, and everything happens behind closed doors, so who knows?

† Does Jesus actually see Moses and Elijah on the mountaintop? The disciples who went up on the mountain with him seem to believe that it happened, but again, the narrator doesn't go up the mountain so beats me.

On the whole, the manga suggests that Yasuhiko doesn't really believe anything supernatural ever happened around Jesus, but he's just leaving his options open to suggest how Joshua (and, by extension, Christians) might believe it. In either case, all this vagueness makes for an uninteresting story, and I'd much rather hear about Jesus hunting vampires, or squeeing over cute High School Girls in Tokyo, than being some distant figure who seems nice but who you just can't understand. In fact, some might say that it's the exact opposite of the appeal of Jesus in Christianity, in which Jesus is appealing because he's human, and not some aniconic unknowable God figure. Alas, manga iconography – to which Yasuhiko, despite his realistic art style, is beholden – tells us that we will not get inside Jesus' head starting from the very first page where he appears. Big-eyed, clean-shaven, bland-looking Joshua has "protagonist face," while Jesus, with his sharp nose and stern eyes and facial hair, looks more like an aniki type at best, too grownup to be the character we empathize with. Nonetheless, both of them look more human than most of the cast. In typical manga fashion, the good guys (and the 'seductive bad guy' Judas) are handsome and delicately featured, and the comical and villainous characters (including the "crude and filthy" disciples) have big noses, big beards and other stereotypical Semitic traits, just as they do in the Christian manga Manga Messiah, a manga by an infinitely less talented artist. I'd call this a cliché rather than a stereotype, an example of Yasuhiko's artistic limitations, despite his ability to draw perfect human figures and epic landscapes of temples and cities and twisted trees. Perhaps an artist like Hitoshi Iwaaki (Historie), whose characters designs err on the side of the bland and expressionless, might be better able to draw people from distant cultures and times without making them look like caricatures; in Iwaaki's manga, everyone looks weird.

I love religious manga, so I had to write about it Yoshikazu Yasuhiko's Jesus, despite its many flaws. It does have some good points – it's well researched, Joshua is occasionally interesting as a character, and the art is good except for the aforementioned problems, the colors are even sumptuous at times (although sadly, it's only available in English as a low-resolution, blurry ComicsOne ebook). For a better manga that really shows Yasuhiko's strengths as an artist and storyteller, check out back issues of Gundam: The Origin (published and canceled by Viz), which is full of action, science and super-detailed robots. As for Jesus, it has plenty of historical exposition but not nearly enough answers. Like Oliver Stone's film Alexander, it makes you think you're going to get inside the mind of an enigmatic historical figure, but it never takes a stand and just makes you more confused than when you started. In the end, it's a manga that leaves you saying "Why have you forsaken me?" rather than "It is accomplished."

Jason Thompson is the author of Manga: The Complete Guide and King of RPGs, as well as manga editor for Otaku USA magazine.

Banner designed by Lanny Liu.

discuss this in the forum (40 posts) |